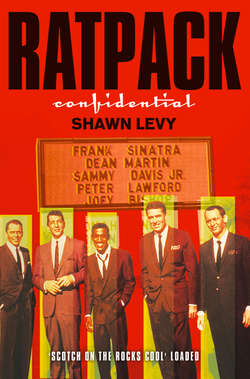

Читать книгу Rat Pack Confidential - Shawn Levy - Страница 11

America’s quest

ОглавлениеPoor Peter.

Try this for a curse: You have looks, breeding, savoir faire, but no real talent other than the ability to deploy your mien to ingratiate yourself to the world; nevertheless, fate rewards you with sex, money, fame, station; you spend a decade or two floating atop a gigantic bubble; you can do no wrong; then it all goes slowly sour; a few missteps, two or three vicious body blows, innumerable little jabs and lacerations, and one day you wake up in your own shit, bankrupt, dazed, strung-out, a laughing-stock, alone—Whatever Happened To You?

You wouldn’t wish it on a dog, but it’s all true. Fortune granted Peter Lawford more for less than anyone ever dared hope, then reneged with such perverse violence that even his most envious enemies took pity on him.

And it all started with such promise. Indeed, in a queer way, Peter Lawford was a sparkling gem in the crown of English glory. Scion of two distinguished military lines, he toured the world as a young boy, conquered Hollywood as a teen, and grafted himself onto America’s royal family as an adult. Handsome, poised, and, in a fashion, deft, he was a perfect figure, to American eyes, of British sophistication. You look at Peter Lawford in 1959, and you’re looking at quite possibly the most fortunate man who’d ever lived.

Which makes a nice twist on this most full-of-twists life. Because on the face of things, there wasn’t a chance in hell that the maimed bastard son of Lieutenant General Sir Sydney Lawford and May Somerville Bunny would ever get anywhere, under any circumstances. A one-in-a-million combination of traits, gifts, habits, predilections, biases, and flaws made and broke Peter—a curse that only May Lawford could have concocted.

Lady Lawford, as she insisted on being addressed with technical correctness but technical presumption as well, was more than just some daft embodiment of Victorian eccentricities and perversions—though she never failed to display such traits in excess. She was a genuinely disturbed woman whose contradictions, pretensions, and megalomania consumed her and those around her—chief of all, of course, her only child.

That May Lawford ever even had a child should be reckoned something of a miracle. In her own words (captured frighteningly in her illiterate memoir, Bitch!), she was repulsed by “that horrible, messy, unsanitary thing that all husbands expect from their wives.” Her own mother, although an otherwise worldly woman, and her father, a physician in the Royal Army, never told her the facts of life, and her first husband, another military surgeon, Harry Cooper, so respected his teenage fiancée’s chastity that he never importuned upon her for so much as a kiss before they wed.

Their wedding night devolved, as might be expected, into a horror show of fright, tears, frustration, anger, Harry finally inducing May with biblical verses about spousal obedience. From this merry start, the marriage went downhill, with sex as the chief sticking point. May grudgingly submitted once a month, and then only lay passively. Cooper endured six months of celibacy until he was posted to India; May didn’t join him. Alone in London, secure in the cloak of marriage, May passed her time in amateur theatricals and a bustling social life. (Where she had mortal aversions to actual physical intimacy, she had none whatever to open flirting.) Cooper received strange reports of May’s behavior and assumed the worst. One night, two and a half years after the wedding, the rejection, rumors, guilt, and grief overwhelmed him: He blew his brains out in his office with a pistol.

Strangely disassociating herself from this ghastly event, May met and was courted by another military surgeon, Ernest Aylen, and married him within two years of Cooper’s death. Once again, the fruits promised by May’s quite modern behavior proved illusory when her wedding night arrived. Aylen, however, was made of tougher stuff than Cooper; his marriage became a kind of swap meet, with sex a form of currency. Once a month, May would allow herself to be “mauled,” but only when rewarded prior to the act with jewelry. “I felt like a tart,” she confessed, “a French tart!”

She didn’t act the part well: In his priapic despair, Aylen lashed out at her, “I’d rather be in bed with a dead policeman!” Claiming his wife’s two favorite bits of pillow talk were “Don’t!” and “Hurry up!,” the wretched doctor cried, “It’s a good thing you don’t have to make your living off of sex; you’d starve to death.”

After nearly two poisonous decades and many separations, the two agreed at last to live apart. As before, separation from her husband afforded May the opportunity to find another. This time she set her sights higher than the army hospital, however. She became acquainted with her husband’s commanding officer, Sydney Lawford, a dashing hero of the war himself mired in an unhappy union.

He was a hell of a catch. “Swanky Syd,” as fellow soldiers branded him in recognition of his sartorial dash, had been knighted for his legendary valor in the fight against the kaiser. His men adored him; women were invariably taken with his combination of physical charm and high rank.

May, though still married to a junior officer in his charge, became a favorite of the general’s, and she reciprocated the attention, if, as usual, a bit grudgingly. When, two years into her separation, she found herself a guest at his sister’s country estate, she allowed him to escort her to her bedroom after dinner; he followed her inside; “Oh, no, not this again,” she thought to herself, but this fish was too big not to reel in over such a qualm. She granted the general her meager favors, and, at age thirty-eight, conceived their only child with their very first intimate act.

When May’s pregnancy became apparent, she importuned upon Aylen to do the noble thing; although the baby wasn’t his, he agreed to stay married to her until it was born, granting it the generous gift of his name. The general, too, convinced his spouse to play along for decorum’s sake. But when the baby, christened Peter, was born in September 1923, there was no saving either marriage: Divorce petitions, filed within days of the birth’s being registered, were granted within a year; one week after that, May and the general were wed.

It may have seemed a coup on paper, but May’s lot was decidedly mixed. The scandal surrounding Peter’s birth drove the Lawfords from the country; they were to live in France, India, the South Pacific, Hawaii, Florida, and California for the rest of their days, maintaining, frequently enough, a sufficiently high standard of living to seem gay globe-trotters, but, in reality, terrified to return home to the hisses of English scandalmongers.

The general, like Cooper and Aylen before him, expected sexual compliance from his wife, but May hit upon an ingenious ruse to keep him at bay, responding to his overtures by “slipping to the kitchen and getting uncooked meat which I rubbed against my nightdress. I was always having my period!” Time was on her side: The general was fifty-nine when they married and soon lost his interest in his wife’s body. “I never,” May boasted, “had sex with him after Peter was three.”

Ah, yes, of course, Peter, the device by which May had landed the general but a horrid encumbrance nevertheless. May said she’d nearly taken her first husband’s way out during childbirth, putting a revolver in her mouth in response to the pains of labor. Delivered of her child, she suffered the indignities of his infancy: “I can’t stand babies,” she groused. “They run at both ends; they smell of sour milk and urine.”

Peter was, whenever possible, fobbed off on nurses and servants. And, of course, being a child of May’s, he was raised with a combination of notions both indulgent and bizarre. “Peter wasn’t brought up, he was dragged up,” said a sympathetic cousin—and the phrase was keenly apt. Like other Englishwomen of her era, May dressed her boy as a girl, but she persisted in the habit, at least in private, until Peter was nearly in his teens. She allowed him to sleep in his parents’ bed until he’d nearly hit puberty and instilled in him a fanatical discipline for cleanliness (a fussiness also shared by Frank Sinatra): He bathed and gargled at least twice every day. And May had ideas about diet, too. Peter was allowed only a strict regimen of fruits, vegetables, whole-wheat bread, and, rarely, meat, with sweets of any sort taboo.

Peter was never formally schooled and spoke only broken English for much of his childhood (French was, in a way, his native tongue); he was probably some sort of dyslexic, but he had to diagnose his problem—and treat it—on his own. Tutelage in nonscholastic matters, unfortunately, was provided him by others: At nine, he became a target of pedophiles, both male and female—a horror that lasted through his teens.

May knew nothing of Peter’s tortures, concerning herself instead with cultivating his desire to playact and perform. A perfect Little Lord Fauntleroy, Peter charmed crowned royals, ships’ captains, film directors, and journalists alike with his impeccable manners and precocity. At eight, he played a part in Poor Old Bill, an English kiddie film. He acquitted himself so well that he surely would’ve received more offers of work had not the general put his foot down—“My son a common jester with cap and bells, dancing and prancing in front of people!”—and hied the family off on an extended sojourn to India and the South Pacific.

It would be seven years before Peter had another chance to act, and then only because of a freak accident that maimed and nearly crippled him. Returning to his parents’ French Riviera home after a game of tennis, he shattered a window-pane and sliced his right arm straight through to the bone. The first doctor to examine the arm declared it unsalvageable. Counseled to amputate, May responded with aplomb—“Fuck off, doctor!”—and found a physician willing to stitch Peter’s muscles back together. The arm was saved. To combat the lingering pain and stiffness, however, the Lawfords were advised to relocate Peter to a dry climate—Los Angeles, say. Although the arm would never fully heal (in its natural state of relaxation, Peter’s right hand was clawlike), it gave him, perversely, his ticket to success.

He found bit parts right away, but it would take five more years of on-again, off-again work before Peter was granted a full contract by MGM. But when the deal was done, it was as near as a twenty-year-old could imagine to a golden ticket from God Almighty.

May and the general thrived as well, becoming staples of the British expatriate community in Los Angeles and earning a reputation as grand old eccentrics among the Hollywood crowd: Frank once asked May about her son, and she responded in what she thought was perfect Hollywoodese—“Peter? That schmuck!”—bringing him to his knees with laughter.

Aside from affording May a society in which she could act the grande dame, Hollywood gave Peter the opportunity to chase every famous skirt in the world: Lana Turner, Rita Hayworth, Anne Baxter, Judy Garland, June Allyson, Ava Gardner … you name her. His appetites weren’t necessarily orthodox: He had chances, for instance, to bed both Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe, but refused the former because she had what he considered “fat thighs” and the latter because her living room was dotted with chihuahua poop when he rendezvoused with her. But he was always being floated in the gossip pages as some pretty young thing’s fiancé, and he was swain enough to travel with sexual gear—towels, blankets, mouthwash, changes of clothes—in his car.

Despite this impressive record of cocksmanship, though, he was constantly plagued by rumors of homosexuality. He was chummy with Van Johnson and Keenan Wynn, and scuttlebutt put all three of them in bed together with Wynn’s wife, Evie (who, in fact, married Johnson within hours of getting a divorce from Wynn). Later on, stories circulated about trysts with other young actors, of loitering in notorious public men’s rooms, of all-boy parties in Hawaii, of Peter’s being “the screaming faggot of State Beach.” Most insidiously, May Lawford responded to her son’s growing apart from her by walking into Louis B. Mayer’s office and telling the prudish studio chief that Peter was a homosexual, a charge that Peter was forced to refute by soliciting the explicit testimony of Lana Turner; the canard drove a permanent wedge between him and his mother.

At MGM, Peter was little more than an English pretty boy, but he had the good fortune of appearing on the scene just as Freddie Bartholomew’s career was in decline. He played light romantic roles well, didn’t shame himself out of the business when he essayed a bit of song and dance, could play gravely enough for small roles in serious drama: a good all-round B-movie lead, or nice support for an A production. He’d never make them forget Olivier, but he was a reliable asset for a studio at something like its height.

Despite his lack of professional distinction, Peter was a highly sought-after invitee, an especially glittering extra in the diadem of Hollywood nightlife; he became known as “America’s guest,” as much for his habit of showing up at every noteworthy party as for his reluctance to pick up a dinner tab.

There was, however, another social group with which Peter mingled and to whom he showed an especially generous and loyal side of his nature. Having been introduced to surfing as a young boy in Hawaii, Peter had a genuine love for beach life, and he spent all the time he could at the shore, catching waves, playing volleyball, and steeping himself in the lingo and rituals of beach bums—a cultish society whose vocabulary and attitudes would later be borrowed, in a fashion, by the Rat Pack. May hated the ne’er-do-well manner of this crowd—which, of course, attracted her son to it even more. Moreover, Peter relished mixing his surfing and acting cronies, watching the cultures clash with sophomoric delight.

As he neared his thirties and seemed stuck on a treadmill of light comedy and dull drama at MGM, as his genteel parasitism grew wearying, two life-altering events befell him. At eighty-seven, General Lawford died contentedly in his garden, so deeply rattling Peter that he initially refused to return from Hawaii and endure the funeral. Nine months later, he found himself engaged once again, seriously this time, to Patricia Kennedy, the strong-willed sixth child of Irish-American Croesus and political dynast Joseph P. Kennedy.

Pat Kennedy was not a soft, obliging Hollywood gal. She was not as pretty as Peter’s other fiancées, nor as sensual, but she was sharp-witted and independent and spunky. She didn’t just throw open her legs for him because he was a handsome movie star who talked nice; she challenged his opinions and stood up for her own beliefs in a fashion that must’ve reminded Peter at least a little bit of May. Peter and Pat drew toward one another with surprising ease, not slaving over one another but respectful of their mutual independence. They were in their thirties and set in their ways; their relationship seemed as much one of siblings as of lovers.

Everyone knew what Pat saw in Peter, but many observers, especially Pat’s very jaded father, Joe Kennedy, saw something suspicious in Peter’s commitment to the relationship: Pat, though smart and vivacious, was no beauty, so Peter’s affection tended to give off a mercenary vibe, at least at first blush; moreover, Joe was appalled at Peter’s baroque Hollywood manner—the actor wore red socks to their first meeting—which seemed to lend credibility to the gossip he’d heard about Peter’s catamitic proclivities.

To satisfy himself as to the first matter, he had Peter agree to a prenuptial pact that protected Pat’s fortune (at the crucial moment, though, he forgave Peter from signing it, satisfied at his willingness to do so). As for the other, he importuned upon J. Edgar Hoover to open his infamous store of Official and Confidential files, which revealed that Peter was a well-known patron of Hollywood prostitutes. Rather than blanch at this evidence of Peter’s moral character, lascivious Old Joe, who approved of hearty sexuality, even in potential sons-in-law, was delighted. The courtship climaxed in a lavish April 1954 wedding. Peter Lawford had graduated from waning pretty-boy actor to American royal—a hot number all of a sudden.

Frank, for one, took notice.

Through the dusty haze kicked up by his killing schedule, Frank had begun to set his sights on something higher than mere success as a singer, actor, or even mogul.

He had always seen himself as a representative man, a “little guy” whose ascent in the world was a vindication of his parents’ immigration to America and his own combative resiliency in overcoming ethnic prejudice, loneliness, and, if you could call it that, economic privation. It wasn’t enough for a guy like that to simply be busy at his job—Sammy, say, was at least as active. No, he had to have an impact on the world.

So in 1958, when it looked like this handsome young senator from Massachusetts, Jack Kennedy, would make a bid for the presidency, Frank decided to become part of it the way he did everything else he was passionate about: both hands, feetfirst, no looking back.

It was a sign of his own success. Into his forties, he had come to see himself as a man of station and discernment, a world-beater worthy of helping shape the future. But it was also a kind of inheritance: He had learned about politics by watching his mother work the ward system in Hoboken. Dolly Sinatra had the barest formal education and should’ve been kept from achieving any kind of power as a woman, an immigrant, as a midwife and abortionist. But she had spunk: She married a Sicilian against her Genoese parents’ will; she dressed up like a man to watch her husband box in men-only joints; she exploited her fair features to pass herself off as Irish; she drank; and she talked like a stevedore, cursing vividly even when, in her dotage, attended constantly by a nun.

Such spirit distinguished her from other Italian mothers of her generation, but not so dramatically as did her political activities. In a corrupt little town run by an ironclad political machine, she won over the kingmakers by consistently turning out the vote and becoming the person to whom her neighbors came for jobs, food, and the sort of generic wheel-greasing and ass-saving they associated with Men of Respect. Dolly, of course, could never hold office, but she had the ears of men who could forgive crimes, erase debts, grant sinecures, and make life bearable or hellish as they chose. With her assistance, scores of Hoboken’s Italians made their way toward the better life they’d come to America to enjoy.

Dolly didn’t achieve her station simply by virtue of gumption. She worked hard at her glad-handing and ward-heeling, and she was even willing to broker her only child for political advantage; as his godfather, she chose none of his five uncles or other male relatives but Frank Garrick, an Irish newspaperman whose uncle was a police captain. The choice proved strangely fateful. In a mix-up that marked the child forever, the priest at the baptism named the boy Francis—for Garrick, whom he somehow came to believe was the father—instead of Martin, the name Dolly and Marty had chosen. Dolly, still recuperating from the delivery, wasn’t at the ceremony to protest, while Marty stood there in characteristically mute impotence, saying nothing as his patrimony was diluted.

For all that she fussed over her boy, for all the clothes and spending cash and good words put in with people who could get him jobs and, later, gigs, Dolly nevertheless found it more exigent to leave him to the care of others and pursue her political work. Frank was fobbed off on relatives and neighbors. Politics, in effect, was the sibling from whose charms he could never divert his mother’s eye; naturally, it came to seem to him an extension of family life, a way of linking up with his absent mother and creating a community around himself.

Plus it had perks. Dolly got Marty a well-paying job in the city fire department despite his inability to pass a written test, and she eventually got him promoted to captain—though few of his colleagues reckoned him worthy of the honor. Comfort and largesse flowed from political power, Frank could see, and when he was old enough to court it he did.

Frank’s political instincts weren’t entirely mercenary. He genuinely felt compassion for the underdog and championed civil rights as soon as he had a platform from which to be heard. In 1945, virtually the moment his career as a solo artist granted him a public profile, he spoke out against prejudice at a high school in Gary, Indiana, where black students had recently been admitted to a hostile reception from whites.

He also godfathered a curious little film project, The House I Live In, a ten-minute docudrama in which he preached a lesson in ethnic harmony to a mixed-race gang of street kids. “Look, fellas, religion makes no difference except to a Nazi or somebody as stupid,” he explained. “My dad came from Italy, but I’m an American. Should I hate your father ’cause he came from Ireland or France or Russia? Wouldn’t that make me a first-class fathead?” Then he launched into the title song, a syrupy ode to American equality, and ended by admonishing his audience of converted Schweitzers, “Don’t let ’em make suckers out of you.” (The film won Special Academy Awards for its creators, including Sinatra, director Mervyn LeRoy, and screenwriter Albert Maltz, a future member of the famous Hollywood Ten group of blacklisted authors.)

And Frank practiced what he preached. He was among the earliest and most visible proponents of civil rights in all of show business. He worked and traveled with black musicians, always insisting that they get treatment equal to that afforded him in restaurants and hotels, and he did what he could to give a boost to such acts as the Will Mastin Trio.

Frank’s political liberalism even led him to a deliberate reprise of the accident that gave him his own name. His only son was always known as Frank Jr., but the kid was actually named Franklin Wayne Emmanuel Sinatra in tribute to, among others, his father’s hero Franklin Roosevelt.

And he didn’t merely communicate his convictions in symbols. On the night in 1944 that FDR beat Thomas Dewey, Frank, in New York for a series of concerts at the Waldorf-Astoria, celebrated with a bar crawl in the company of Orson Welles. The two decided to cap their gambols by razzing right-wing columnist Westbrook Pegler, also resident at the hotel. They rowdily pounded the door to Pegler’s suite to no satisfactory response, then returned, discouraged, to their debauch.

Four years later, Frank won $25,000 on a bet that Harry Truman would be reelected. In 1952, Frank campaigned for Adlai Stevenson, and then again in 1956, when he sang the national anthem at the opening session of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and stuck around to get a close-up look at the action. (He caused some of his own as well. After he sang “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Frank was on his way offstage when he was grabbed by Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, who asked him if he’d also be performing “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” “Get your hands off the suit, creep,” Sinatra replied.)

It was there that his eye was first caught by Jack Kennedy, then a dazzling, photogenic young senator with a pretty wife and a baby on the way. After Stevenson had secured the presidential nomination, he’d thrown the vice-presidential slot to the convention without naming a candidate of his preference; Kennedy, against his father’s wishes, sought the spot and was locked in battle for it with Tennessee’s Mafia-baiting senator, Estes Kefauver. Frank hung close to the Kennedys as the convention progressed, impressed with the amount of money and degree of organization the family applied to the campaign. When Kefauver won the nomination, the Kennedys were briefly stunned.

Then Frank noticed Bobby, the senator’s younger brother and campaign manager, telling folks around him, “OK, that’s it. Now we go to work for the next one.” The stubborn will in those words was invitingly familiar, an echo of Dolly’s gumption. Frank determined to keep tabs on Jack Kennedy.

He just needed an in.

And what do you know: At a dinner party at Gary and Rocky Cooper’s house in the summer of ’58, there was Peter.

Frank had seen Lawford among his in-laws at the Democratic convention two years earlier; he was working, incongruously, with Bobby, trying to gain support from the Nevada delegation, which was run by Peter’s sometime Desert Inn boss, Wilbur Clark.

At the time, even though they’d been chummy at MGM in the forties, Frank was carrying a grudge against Peter—a misunderstanding about a woman. In late ’53, after she and Frank had split, Ava Gardner had a drink with Peter at an L.A. nightspot. When Louella Parsons reported the little tête-à-tête, Frank went bonkers, calling Peter at two in the morning and shouting at him, “Do you want your legs broken, you fucking asshole? Well, you’re going to get them broken if I ever hear you’re out with Ava again. So help me, I’ll kill you.”

Peter was terrified: “Frank’s a violent guy and he’s good friends with too many guys who’d rather kill you than say hello.” He asked a friend to intervene, and when Frank realized that it really was just an innocent drink, he cooled off. But he didn’t bother with Peter until he’d become a Kennedy, and even then grudgingly. Pat Kennedy, presuming with some reason to install herself as a society queen in Hollywood, had tried for years to have Frank attend some or other event; he had always brusquely refused her.

But as her brother’s star rose, and as Frank’s interest in politics merged subtly with his naked ambition, Peter’s near-trespass didn’t seem so awful. So it came to pass that on that fateful night at the Coopers’, with Peter working late at the studio on his Thin Man TV series, Pat found herself rapt in conversation with Frank, who had gone out of his way to break the ice with her. Dolly Sinatra’s boy, ever aware of who held the power, knew that she could provide quite a high level of access to what was clearly a growing political concern.

When Peter arrived at the party—bandaged after an injury on the set—he was amazed to discover his wife and Frank amiably chatting. He quietly took a seat at the table, not knowing what sort of greeting to expect. Frank looked at him, then looked back at Pat and said, “You know, I don’t speak to your old man.” The two of them laughed, and Peter did, too, a beat later, when he realized he’d been forgiven.

Within a few months, a suddenly intimate relationship formed between Peter and Frank. When Pat had a daughter that November, the child was christened Victoria Francis—the first name in recognition of her Uncle Jack’s reelection to the Senate that day, the second in recognition of Frank.

The following year, vacationing together in Rome, Frank actually apologized to Peter for the way he’d blown up over Ava: “Charlie, I’m sorry. I was dead wrong.” It was the rarest of moments: another smile of fate upon Peter Lawford.

He and Frank became fast pals, frat brothers with nicknames, booze, broads, matching cars. He got work: the Pacific theater war movie Never So Few, his first picture in six years, came his way strictly because Frank insisted on it—and at a price that made MGM choke, also at Frank’s insistence. The two became partners in a Beverly Hills restaurant, Puccini, and served spaghetti and chops to the stars; Frank was so glad to have Peter on board that he put up both halves of the seed money.

And Frank had his avenue to Jack Kennedy. Peter admitted that he and his wife “were very attractive to Frank because of Jack.” Sure enough, once he was connected, Frank leapfrogged over the guy he came to call “the brother-in-Lawford” and ingratiated himself with both Jack and Old Joe.

Indeed, though his cavorting with Jack was famous, Frank may have been closer to the father, the primary source of money and power in the family and the one most familiar with the courtship of disreputable outsiders, whether they were mobsters, corrupt politicians, larcenous power brokers, or temperamental pop stars. Joe had, it was said, prevailed on Sam Giancana to help erase public records of Jack’s annulled 1947 marriage to a Florida socialite; he called upon the Chicago don again in the late fifties to smooth things between himself and Frank Costello when Kennedy’s reluctance to recognize his obligations to the New York mobster almost resulted in a contract on his life; later, during the 1960 presidential campaign, he was seen dining at a New York restaurant with a select group of top mobsters from around the country. Jack may have had all the buzz, but Joe was, in Frank’s eyes, the real man of the world in the family.

If Jack didn’t inherit his father’s intimacy with the ways of men of dark power, he had plenty of Joe’s lustful wantonness. In this, Frank made a perfectly agreeable playmate, especially when it came to the young senator’s favorite diversions—women and gossip. The two began partying together soon after Frank reconciled with Peter—“I was Frank’s pimp and Frank was Jack’s,” Lawford ruefully recalled. “It sounds terrible now, but then it was really a lot of fun.”

Whenever Jack came to the West Coast for fund-raising or other official duties, he made sure to hook up with Frank, more often than not with Peter in tow. They didn’t hide their budding friendship from the press: “Let’s just say that the Kennedys are interested in the lively arts,” Peter told a reporter, “and that Sinatra is the liveliest art of all.”

In November 1959, Jack extended a trip to Los Angeles by spending two nights at Frank’s Palm Springs estate. Frank got a huge belly laugh out of him by introducing him to his black valet, George Jacobs, and suggesting that the senator ask the mere servant about civil rights. “I didn’t like niggers and I told him so,” Jacobs remembered. “They make too much noise, I said. The Mexicans smell and I can’t stand them either. Kennedy fell in the pool he laughed so hard.”

Fun over, Jack had to return East, even though he would’ve just loved the next night, when Frank, joined by Joey Bishop, Tony Curtis, Sammy Cahn, Jimmy Durante, Judy Garland, and about a thousand others toasted Dean at the Friars Club. But he made a mental note to catch up with them the next time they’d all be together: the following winter in Las Vegas when they’d be making a movie.

It was one last bit of patrimony thrown Peter by his new best friend. Frank had taken a literary property off his hands: Ocean’s Eleven, a movie about a group of World War II vets who hold up Las Vegas.