Читать книгу Revenge - Sheldon Cohen - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 5 Pollard would be meeting two junior medical students assigned to him for a three-month clerkship in emergency medicine. Every three months two junior students from the University of Illinois College of Medicine would rotate through the service as a self-chosen elective. More often than not, the students were contemplating an emergency medicine residency, and what better way to get oriented to the service then by working with Dr. Pollard and his staff.

ОглавлениеThis was the students first clinical day, and Pollard looked forward to filling their pliable and receptive minds with all the clinical pearls they were capable of retaining; and plenty of pearls were there for the taking. He enjoyed teaching medical students almost as much as he enjoyed the daily diagnostic challenges that came through the busy Emergency Department. He always maintained, “Medical students slow you down a bit, but they keep you sharp and on your toes.” The latter, he was sure, outweighed the former.

The two medical students were sitting in his office when he got there. They were dressed in white lab coats with a picture identification badge on their left upper pocket. Pollard met them the week before for a two-hour orientation that covered Emergency Department operation, rules and regulations, and student expectations.

He looked at their enthusiastic faces. “Hi,” he said, “sorry I’m a little late. It looks like we’ll be getting busy soon. I just received a call from the paramedics telling me they’re bringing in a man who is quite sick. He should be here in about ten or fifteen minutes.”

The two students, both from Chicago and both juniors at the University of Illinois College of Medicine nodded. Although they were in the same medical school, the G and J of their last names managed to keep them apart their freshman and sophomore years. This experience would be the first time they would work together. They both planned to pursue a career in emergency medicine. They viewed the opportunity of mentoring by Pollard as a very fortunate development in the pursuit of their goal.

Amanda Galinski stood five foot seven inches tall with short, wavy brown hair, brown eyes, and orthodontically engendered straight white teeth that accented her pretty face and smooth, blemish free skin. As was her habit, she was devoid of any make up except for a faint pink blush on her cheeks. She wore no earrings or other jewelry, as there were no accessories worn by any Emergency Department personnel except for a watch on their wrist.

Barry Johnson stood tall and straight at six feet two inches. He weighed two hundred and twenty pounds. His black thinning hair was long and combed over the balding spots. His penetrating dark eyes seemed to look right through you with nary a blink. His well-muscled body, visible even under his lab coat, conveyed the message that this man was serious about staying in excellent physical condition. This mind-set was honed as a high school basketball player and continued as the recipient of a basketball scholarship to the University of Illinois where he played point guard, operating as sixth man. Although he lacked speed and jumping ability, he was a phenomenal three-point shooter and they used him often when three point shots were vital. Because of this skill, he acquired the nickname of “bullseye.” Barry was quiet and reserved and although Amanda did not know him, she did remember watching him play when she too was a pre-med student at the University of Illinois. His dark good looks impressed her.

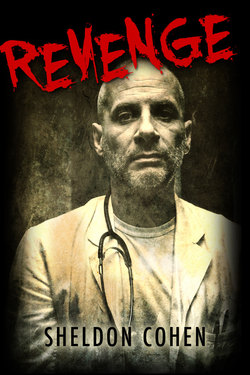

Pollard was six foot three inches and weighed 195 pounds. He had light brown, almost blonde hair. He was forty-five years of age. His lean frame honed by competitive tennis, was a means of warding off the burnout so common in emergency medicine physicians. He wore a white lab coat opened at the front, and with coat tails trailing behind him he sped wherever he went. A bright red stethoscope draped around his neck and in his chest pocket was a plastic liner onto which was clipped six different ballpoint pens. He wore gray SAS walking shoes.

Pollard sat behind a large L shaped desk. To his left was a flat screen computer terminal. Behind him was a built in wall bookcase, one shelf of which was filled with books in all fields of medical specialization. Emergency medicine journals occupied another shelf. Standing on the right corner of his desk was a picture of his wife, Sarah and their six children. Off to the left of the bookcase were four diplomas: University of Illinois Medical School, Illinois State Licensure, Residency Certificate, and Emergency Medicine Board Certification. Conspicuous by their absence were numerous academic awards and honors never framed and stored in his closet at home.

Pollard addressed the students. “While we’re waiting for our first patient, I’ll tell you the clinical facts that I’ve been told. This is a man about sixty who is unconscious and had a seizure. In addition, he has a temperature almost 104 degrees. What do you think we might be dealing with?”

Amanda said, “Brain tumor?”

“That’s a good thought. A brain tumor patient may have a temperature, but this one is quite high, more than one would expect, unless of course part of the tumor died. Then he could have a higher temperature.”

“I have two possibilities,” said Barry, “either a vascular accident like a cerebral hemorrhage or thrombosis, or a meningitis.”

“Both good thoughts,” said Pollard. “One could have a fever with a cerebral hemorrhage, but you wouldn’t expect it to be that high again, so your second suggestion would be the better one. We see very little meningitis in the Emergency Department. It’s logical to think of the brain as the etiology of these symptoms, so you’re wise to zero in on this source, but you need to know there are plenty of other non-cerebral problems that could cause coma, seizures, and an elevated temperature. So we’re dealing with many possibilities, and we’ll try and sort them out when we see the patient. We’ll use our powers of observation, if we have any, and we’ll see what a physical exam can add to defining the problem. Any other questions while we wait?”

The students shook their heads. “No, sir.”

“Okay, when we’re together and in front of patients I’ll call you Dr. Galinski and Dr. Johnson. You’ll call me Dr. Pollard.”

The students nodded.

“One more question,” said Pollard. “What have you got to work with here?”

Both students stood silent. There was no answer forthcoming as they turned and looked at each other.

Pollard laughed. “Silence…That’s what I always get and that’s what I expected,” he said, “so don’t feel bad…you passed, and that brings me to the answer, but first a little lecture. This is your chance to polish your physical diagnostic ability. We make initial diagnoses here using four things: our sense of sight, hearing, touch and smell, aided by our hand held medical equipment and our brain. We use high tech when we have to. If you do a good history and listen to the patient, and do a good physical examination you will make a diagnosis at least 80 percent of the time. That’s not me talking, that’s Sir William Osler, and there were never any truer words describing the practice of medicine. That’s one way I’m going to judge you in these three months. So expect two questions from me after you see a patient: what is the medical history and what are the physical examination findings. After that I’ll want to know your diagnostic impression and then all the treatment options. Simple. It’s a ritual…and that’s how we learn. There will be no shortage of clinical material. Am I clear?

“Yes, they both answered.

“One more thing,” said Pollard, “we have a tremendous volume of patients here. So what I just told you is ideal, but when you get to be an emergency medicine physician, you’ll discover that you may not have the time it takes to do a thorough examination. In my case, there’s where you students come in. You may see a patient first. You’ll tell them Dr. Pollard, or whoever will see you soon. You’ll introduce yourself, tell them that you’re a medical student and you’ll see them, take as good a history as you can, do the best exam you can, and then when I come in we’ll work together. Now, all that assumes that the patient is conscious and rational and can give a history. There will be plenty who won’t be able to. Understand?” he said without looking up.

Before the students could answer, Gail entered. “The paramedics are pulling in with your patient, Dr. Pollard.”

He shook his head in acknowledgement. “Mrs. Cowan, this is Amanda Galinski and Barry Johnson. They’ll be working with us for three months as part of their junior clinical clerkship.” Getting up from his desk and turning to his students he said, “Now you two listen up. Mrs. Cowan will also be orienting you, and if I’m not around and you have any questions you’re free to ask any doctor on duty, but if you want my advice you’ll ask Mrs. Cowan. She knows more than all of the doctors put together and that includes me.”

“He says that about all the nurses,” laughed Cowan.

“Okay let’s go see our first patient.”