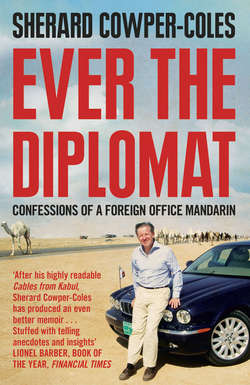

Читать книгу Ever the Diplomat: Confessions of a Foreign Office Mandarin - Sherard Cowper-Coles - Страница 6

ОглавлениеPreface

This book is really a long love letter to an institution – the Foreign Office – for which I worked for some three decades. From the age of twenty-two until I was fifty-five, I was a British diplomat. Formally, I was a member of Her Majesty’s Diplomatic Service, with a commission from the Queen. But for me diplomacy was much more than a job, or even a profession: it was my way of life. It was what I got up for in the morning, and what I went to sleep at night thinking about. For thirty-three years, I looked forward almost every working day to going into the office, or embassy, or wherever work took me. I was never bored. And I didn’t just enjoy being a diplomat. I also believed that what I did as a diplomat mattered in small but important ways. From Ireland to Israel, and Arabia to Afghanistan, in Paris or Washington, in long hours in London worrying about Europe’s future or Hong Kong after the handover, I tried as a minor cog in HMG’s foreign policy machine to make the world work better. I met the people who helped or hindered our efforts. I went to the places where foreign policy happened. I cared about the issues. And at the end of it all I wanted to share some of the highlights and low points, as I remembered them. I wanted to give the reader a flavour of what diplomats really do, and of what being a diplomat actually feels like. But mostly I wanted to show why I had enjoyed it all so much.

I kept no proper diary. The random private papers I did keep are now buried beyond easy recovery in barns and attics in Britain and France. I have made no use of official documents. But what I do have is memories: plenty of them, good and bad, of the tough times and the bright spots, of the fun I had, but also of the horrors I witnessed and of the mistakes we made. Of the people too, conscientious mostly, committed and often courageous, but some charlatans as well and others with more reptilian qualities. I have set down, place by place, post by post, the best and worst of those memories. All are the truth as I remember it, but not always the whole truth. The story stops at the edge of private turmoil. It alludes only in passing to the disreputable deal-making over top jobs that led me to choose early retirement, five years sooner than expected.

As with my first book, Cables from Kabul,* I have asked myself whether publishing an account of my experiences so soon after I left the public service was consistent with my obligations to my former employer. But Diplomatic Service Regulations state that ‘The FCO welcomes debate on foreign policy … The FCO recognises that there is a public interest in allowing former officials to write accounts of their time in government. These contributions can help public understanding and debate … there is no ban on former members of the Diplomatic Service writing their memoirs … but obligations of confidentiality remain …’

Like Cables, this book is the fruit of a conversation with my future agent, Caroline Michel, at a dinner at the Irish Embassy in London in 2009. It was Caroline who first suggested that I had a book or two in me. It was she who told me to set down my memories and share them. I shall be forever grateful to her for sticking so faithfully to that judgement.

I am also immensely grateful to the team at HarperPress who have given such enthusiastic and wholly professional support to this project: in particular my editor and friend, Martin Redfern, a diplomat if ever there was one, whose quiet judgement has often saved me from error, and who has driven the whole thing forward with determination and discrimination; to project editor Kate Tolley for putting the book together with efficiency and taste; and to Helen Ellis, publicist sans pareil, Minna Fry and the whole of the HarperPress gang.

I owe my research assistant, Max Benitz, a particular debt of gratitude for his hard work in establishing what really happened, in tracking down key documents or photographs, and in offering many excellent suggestions, all done with remarkable accuracy and to time. I have also been extraordinarily lucky in my copy-editor, Peter James, an Oxford contemporary, and in having had the help of the king of indexers, Douglas Matthews.

Two people have given me exceptional support and encouragement as I conceived and wrote this book: my friend Charles Richards and my wife Jasmine. I must also thank a number of former colleagues, including Nigel Cox and Andrew Patrick, for help and suggestions with different parts of the text. As with Cables from Kabul, we have had outstanding help and support from the Cabinet Office in clearing the text around Whitehall: I am very appreciative.

The mistakes which remain are my responsibility alone.

Ealing, July 2012