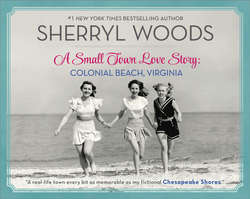

Читать книгу A Small Town Love Story: Colonial Beach, Virginia - Sherryl Woods, Sherryl Woods - Страница 12

ОглавлениеA STORY OF FAMILY AND FARMING:

Mildred Grigsby

Mildred Grigsby, at ninety-four, is a study in contrasts. Her petite frame dwarfed by a large recliner and wrapped in a blanket featuring one of the World Wrestling Entertainment’s superstars, she’s well-known in Colonial Beach for the delicacy of her crochet work, mostly done as she sat on the back of a truck while selling vegetables by the side of the road.

The needlework skill is something she believes her mother must have taught her at an early age, and it was something she took to that kept her hands busy as she sold those vegetables and raised her large family. Her beautiful doilies, tablecloths and table runners are prized possessions in homes all over town and a stark contrast both to that WWE throw and to the hardships of growing up working on the family farm.

Mason Grigsby with one of his daughters

“I think everyone must have at least one thing she crocheted,” her granddaughter says.

Mildred Martin had eight brothers and sisters, all raised on a farm just outside of town. She and one brother are the only ones still living. She and her husband, Mason Grigsby, had six girls.

“Any boy that came along would have been spoiled to death,” she jokes.

The family’s ties to the land go back a generation or more. Her parents had moved to the farm from Maryland before she was born. She went to Oak Grove High School, six miles from Colonial Beach, where many of the locals were bused for several years until the high school returned to the “beach.” She recalls walking to school.

In another of those contrasts that mark her long life, she compares the solitude and hard work of farming with the excitement of a visit to the beach, even though it was only a few miles away. She remembers going to Colonial Beach on the weekends as if it were an adventure far from home. It was certainly a far cry from the life on the family farm.

Concrete boardwalk, 1930s

Mildred and Mason Grigsby

Back in the 1930s and ’40s when she was a girl, the boardwalk wasn’t a boardwalk in the traditional sense. It was made of concrete, and in fact, there was a street running along beside it. She remembers going to the Klotz store for penny candy. “They had everything you needed there,” she says.

On the boardwalk in those days she recalls the bowling alley, the dance hall and roller-skating rink, beer places and bingo, a shooting gallery and, of course, the storefronts that sold snowballs, popcorn and peanuts. There were lunchrooms that sold hamburgers and hot dogs, too.

“There was a lot to do from May 30 till September,” she remembers. She says she never went to the dance halls or pavilions, “but I loved to bowl.”

In later years she even worked as a waitress in some of the restaurants along the boardwalk, and she can list some of her favorite places in town back then—Caruthers and Coakley drugstore. Mrs. Kennedy’s icecream stand, the Emporium on Hawthorn Street, the old A&P and Wolcott’s Hotel and Restaurant.

Alice’s Big Bingo game on the boardwalk

When she married Mason Grigsby, they had the ceremony on Christmas Day. “He worked and I worked. I was on vacation. He worked at a gas station.” Christmas was the one day they were both off.

She was working in a pants factory in Fredericksburg by then, along with several friends. For ten years they piled into a station wagon and made the trip to the factory together.

For years after that she worked as a waitress in the original Wilkerson’s seafood restaurant at Potomac Beach, just outside of town. When that restaurant closed, she looked for something familiar to do, and it took her back in a way to life on the farm. She opened a vegetable stand along the side of the road on property that she and Mason owned.

“We grew some stuff, but mostly we bought from farmers’ markets,” she says.

Her daughter Shirley Hall adds that they would go to markets in Maryland and down the road in Tappahannock to buy vegetables throughout the summer. And while she sat by her truck selling those vegetables, Mildred crocheted.

By then Mason was working for the police department. From there he went to work at Cooper’s, a store that claimed to “sell everything.”

Mason was involved in anything in town that Bill Cooper asked him to do, Mildred recalls. He volunteered with the rescue squad and the fire department.

Eventually Mason began a carpentry business, doing the sort of work he loved. He even taught woodworking at the school. He worked at carpentry till he died.

All of her girls graduated from the school at the beach, married and stayed in the area.

Mason Grigsby during his carpentry days

“We’re a close-knit family. We had to take care of Mama and Daddy,” Shirley says. Those tight-knit ties were something Shirley’s parents had taught them, lessons Mildred had learned from her own family.

Shirley also recalls that she and her sisters were the cleanup crew when their father did his carpentry work.

“We’d go hunting with him and he’d have us barking like dogs,” Shirley remembers. They hunted for deer, caught frogs and trapped muskrats.

None of that was as hard as farming, Mildred says. Her family raised corn, wheat and vegetables. They’d take it around by horse and wagon to sell. “That was before trucks.” When they finally bought a truck, it was because “Granddaddy said we’ve got to give the horses a break.”

The girls in the family didn’t take the vegetables around to the customers back then. “Daddy declared it wasn’t woman’s work,” Mildred says. “I used to think when I was sitting by the side of the road with that truck, I wonder what he’d think about this.”

For all of the memories, though, Mildred is focused mostly on the family that surrounds her. She has a great-granddaughter and a great-grandson, who were both born on her ninety-fourth birthday.

The memories are nice, she says, but family is the thing that matters.

Mildred and Mason Grigsby with two of their great-grandchildren