Читать книгу Season of Violence - Shintaro Ishihara - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The stories in this collection of translated works are, in a word, shocking. They are shocking for their content no less than for their being completely different, image-breaking portrayals of postwar Japanese youth. These three stories are important as social documents just as they are important as literature, but for the reader without firsthand knowledge of Japan to fully appreciate their significance and their influence on modern Japan would be asking too much. Therefore, the translators feel that a brief general background here would greatly enhance the appreciation and understanding of this book. By placing the book against the background of its original publication as well as alongside of the events its publication spawned or influenced, the reader will, we hope, sense the significance of these stories all the more.

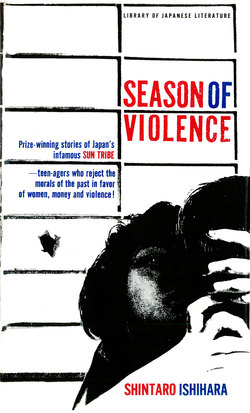

A few years ago the coveted Japanese literary award bearing the name of the late Ryunosuke Akutagawa (author of Rashomon) was given to a 25-year-old author for his second novel. The novel was Taiyō no Kisetsu and the young author was Shintaro Ishihara. The novel had been a runaway best seller and the ever-alert Japanese film studios immediately capitalized on the book's fame by making a motion picture that proved controversial and, of course, very successful. The wild, willful, and seemingly amoral youth of the story and the large segment of Japanese teenagers who adopted these fictional characters as their own, became known collectively as taiyōzoku (literally, sun tribe). The symbolic head of this clan was the protagonist of the story, Tatsuya, personified in Shintaro Ishihara's younger brother Yujiro, the star of the film. The Taiyozoku films that followed firmly established the author's brother as a leading young actor, the "James Dean of Japan." The Taiyozoku of the film were imitated in action and dress, and often in irresponsible action, by the erstwhile Taiyozoku of real-life modern Japan. Parental pressure that had mounted against the book became all the more vehement as films in the genre continued to be ground out by the studios. As a result, Shintaro Ishihara, through his fictional characters, became a spokesman for the postwar generation, and his character Tatsuya, in the form of Yujiro Ishihara, the personification of that generation and its revolt. Though the picture of the present generation of Japanese just described completely contradicts the average overseas image of the Japanese—especially the image of the student generation—as a mild-mannered, diligent breed, it is a part of today's Japan. Japanese student riots have generally shocked the rest of the world, but the unpublicized everyday violence and callousness of the Sun Tribe is an even more shocking revelation of a basic social situation born in the ashes of defeat in World War II.

Taiyō no Kisetsu in book and film form did not spark the so-called revolt of the younger generation in Japan, but it helped give it form. It supplied heroes to imitate in physical appearance and swagger, it supplied rationale for irresponsible behavior, it explained in brutal and dynamic terms the motivation of the "blameless" postwar generation, and it supplied a rallying point for those who wanted to point at some creed (or lack of it) and say "that's how it is with my generation." Taiyō no Kisetsu and the Taiyozoku share a good deal with segments of postwar young people everywhere, but the whole phenomenon of this large-scale mass identification and imitation came as a shock even to the Japanese people themselves.

Taiyō no Kisetsu, here translated as Season of Violence, is a story of wanton young people who reject the world of their parents and all its rules of decent behavior, hardly pausing in their headlong plunge into the world of experience, of "doing what I want." The Punishment Room (also made into a film) and The Yacht and the Boy develop the same theme, so that the three stories form a trilogy of sex, violence, senseless brutality, and revolt against old laws of decency. Japanese critics have pointed out that these stories may be significant more for what they say than for how they say it, but this does not gainsay the power of the writing. Readers will sense the guiding hand of an author who was himself born into the postwar world and who speaks passionately through his characters of this period of great trial in Japan. Postwar Japan has been called a country which lost its moral code when it lost the war. Much good was rejected when the old ways were discarded on defeat in the war. The whole postwar world had its share of living for today and not caring about tomorrow, but Japan's utter defeat and rejection of the past may explain the extremity of this attitude among Tatsuya and his fellows.

The translators hope that these English versions of three Ishihara stories do justice to the original Japanese versions and relay to Western readers the stories' original impact. We have tried to be true to the original Japanese without going to the extreme of translating literally anything that would detract from smooth reading and understanding. Some of the time sequences are confusing, but they are also confusing in the original and are an integral part of the mood which Ishihara creates. Certain remarks are ambiguous in the original and we have tried to give the reader the same freedom of interpretation in English that the Japanese-language reader had.

Though it is a minor matter, those unfamiliar with Japanese currency may wonder at the amounts of cash that often change hands in these stories. Ten thousand yen, for example, is only about thirty dollars in U.S. currency, so that while the violence and cruelty of the characters are meant to be taken literally, the thousands of yen used may be converted in the reader's mind to sums of dollars of less staggering dimensions.

The Translators