Читать книгу Sumi-e - Shozo Sato - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSuiboku-ga and Sumi-e

Sumi-e is commonly described as art done in monochrome, with the use of sumi ink and handmade paper. Sumi-e means “black ink painting” (sumi = black ink; e = painting). The ideogram 墨: which is read sumi in Japanese can also be read as boku in Chinese, and as is true of most Asian art and culture, the roots of Japanese painting are found in China.

The early stages of monochrome art became a recognized genre during the ninth century in China, and suiboku-ga (sui = water; boku = sumi ink; ga = painting) was gradually disseminated throughout the Far East. These paintings were usually done on silk. Later, when handmade paper became readily available, the spreading of sumi ink upon that new, absorbent surface created another, different form of monochrome painting which has a more direct spiritual connection with the artist: sumi-e.

I have elected to make a definitive distinction between suiboku-ga and sumi-e styles of ink painting, because technically speaking, suiboku-ga, which was developed from the “outline” painting done on sized silk, came before the art that is produced with minimized strokes in sumi ink—sumi-e. Internationally, and especially in the U.S., all monochrome art that uses sumi ink has been called sumi-e. Very little has been written about suiboku-ga in most English-language texts, and in most publications on the subject the terms sumi-e and suiboku-ga are used interchangeably.

But being aware of their differences helps you to see that there are “two sides to the coin” in monochrome art, and helps you to recognize how philosophy is an essential underpinning to this art. As well, a brief look at their contrasts offers a glimpse of the rich history that ink painting has absorbed and reflects today.

Suiboku-ga is based upon the Chinese word sui un sho ga (sui = water; un = spreading in gradation; sho = distinct representation; ga = painting). Since the word suiboku-ga contains the additional concept of “water,” it has more complexity in contrast to the simpler word sumi-e.

Suiboku-ga is commonly painted in greater detail with overlapping brush strokes, and in addition, it may be large in size. Obviously, the literal definitions of the words mean that if a work contains great detail with many brush strokes in black ink, it can also correctly be termed sumi-e or boku-ga; but suiboku-ga would be a more formalized terminology for this type of work.On the other hand, paintings which are produced with minimal strokes are the ones I prefer to call sumi-e.

Paintings have been important to humankind from ancient times. Long before it would reach across the water to Japan, the influential Northern Sung style of paintings had its beginning in China during the first and second centuries of the Han Dynasty (221 BC–AD 221). In the Han Dynasty black ink was used for creating “white paintings”: an outline of sumi ink was drawn, then filled in with brilliant colors to create multicolored paintings. Eventually, white paintings without pigments added became recognized as a new genre of art. Then, during the Northern Sung period (960–1126), brush strokes in sumi began to be used within the outlines, instead of color, to further enhance the subject. The overall impression of these paintings was grand but somber, and carried a hint of oppressiveness. Northern Sung styles continued to prevail during the subsequent Southern Sung period (1127–1279) but new methods were also being introduced. Artists began to use the brush sideways to produce a gradient of different tones in sumi ink, which offered in another way to render the subject, often without using outlines. These were the foundations which led to the developing of paintings done solely in sumi ink.

The major contributions to Chinese painting as we know it today began with the Northern and Southern Sung periods, and continued through the dynasties of the Yuan (1280– 1368), the Ming (1368–1644), and the Ching (1644–1912). The imperial courts of each of these dynasties established a system where court-appointed masters in painting produced artwork expressly for the emperor and other royalty. These master artists were given ornamental belts and studios within the royal compound and they proudly displayed their belts to show rank. However, individual rulers promoted their own cultural heritages (be they Han, Mongolian, or Manchurian) via their master artists’ brushes, and also influenced the nature and subject of the artworks, leaving little creativity to the artists. For example, if the Emperor built a summer palace, he might request that the artist make paintings suggesting coolness for the walls and doorways. The artist’s job was to visualize what the emperor wished and then carry it out. To do this it was necessary for the artists to have thorough knowledge in style and techniques, but the original ideas and the artistic sensibility belonged to the patrons. Even so, during this long period of the court-appointed artist system, artwork did not remain static and the artistic approach to paintings did continue to change.

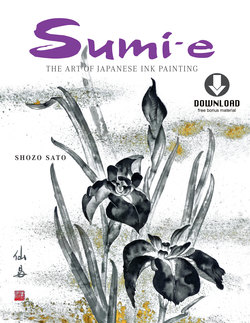

This shobu iris was painted using traditional Japanese pigments, with sumi in the background pattern. Chapter 5 explores this technique further.

Throughout the long history of China, the work of scholars, government officials, wealthy landowners and other members of the educated classes included the transcribing of documents and the writing of literature. These gentlemen of letters were accustomed to using brush and ink on paper when recording documents or writing poetry. They did not have professional training in painting techniques but especially during the Southern Sung dynasty, as a hobby, many began to add simplified artwork to their poetry; it was natural enough, since they were so familiar with the use of a brush. Thus began the merging of poetry with artwork.

Generally speaking, the literati did not use the rigid outline technique in these simplified paintings but began to use the brush in innovative ways. Artwork by the court-appointed artists was often criticized as lacking in vitality and as being stagnant; the literati, on the other hand, were using their own creative ideas, and their spontaneous and energized methods in painting were a refreshing change. Their simplified but sometimes bold use of the brush would often capture the spirit of the subject, and could convey a wide range of expression, from dynamic power to elegance and tranquility. This is the art style that I term sumi-e.

Zen Buddhist monks from China introduced the Northern Sung style of paintings to Japan during the Muromachi period in the fourteenth century. These works reflected the oppressive grandeur that was so characteristic of the Northern Sung. During the fifteenth century, as the monks brought the newer, more flexible styles of Southern Sung and Yuan to Japan, new trends in artistic expression began there.

This was also a time when other great changes were taking place in Japan and the warrior classes came to power. With the advent of the Tokugawa Shogunate system of government in 1603, a new era of social stability emerged in the nation and there was now time to cultivate the arts. Zen Buddhism exerted a powerful influence on the warrior classes who no longer were required to spend time in endless territorial or civil wars. A newly developed pastime for these upper classes was chado, tea ceremony, which influenced Japanese arts of all kinds toward greater elegance and refinement.

During this same period in China under the Ming and Ching dynasties, in place of the black ink outlines, a new style of art emerged using vibrant and opulent colors. Limited by the court-appointed artists system, this art too reached a point of stagnation. But when the Ching Dynasty came into power, the emperor promoted literary education as well as suibokuga in the style of the Southern Sung. As a consequence art reached a high point in refinement, both in craftsmanship and artistic expression.

However, the literati throughout these periods refused to be caught up in the trends and fashions of the times and retained their belief that paintings should capture the spirit (not all the physical details) of the object or theme. From their viewpoint, intricate paintings with minute details were merely an “explanation”; they did not convey the spirit of the subject. Compared to the art’s beginnings based in Northern Sung style, the brush strokes were now reduced in number and simplified and were often combined with poetry. This style of painting, whether done by the Chinese literati (wen jen) or the Japanese literati (bunjin), suggested the subject, rather than describing its details. Importantly, the bunjin artists also recognized the importance of active empty space: the viewer was stimulated to become a participator in the painting. This active empty space is an important component of the style.

Also during the Ming and Ching dynasties, another style of color painting was developed that adapted some sumi-e brush handling techniques. Unlike the sumi-e approach where several tones of sumi were applied to the bristles of one brush to create a gradation, this time, color pigments were applied to the bristles to create a gradient blend of colors. Often black ink was also incorporated as part of the painting. This technique is still commonly seen in contemporary Chinese paintings.

Even this very brief history of the emergence of painting with sumi (black ink) shows us that in both suiboku-ga and sumi-e, and even in paintings using color, the focus of the art of ink painting since its inception has been on the quality of the line; this is what captures the form. In the art of the West, the focus is generally more on color to develop the form.

As we move on to the details and process of creating ink paintings, we will look at and create paintings of both kinds, in order to understand suiboku-ga and sumi-e more deeply.

Although it is composed of only a few types of sumi-e strokes—wide to wide, wide to narrow, and narrow-wide-narrow—bamboo can express many moods. The empty space at the right top plays an active role.