Читать книгу Flower Mat - Shugoro Yamamoto - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеIN RECENT years it has become increasingly fashionable to proclaim the end of national particularities and the gradual extension over the globe of standardized habits of thinking, feeling, and consuming. While this vision of the evolution of human society is an oversimplification, it is nevertheless true that if Kipling had been born only a decade or two later he might never have written the famous words, "East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet."

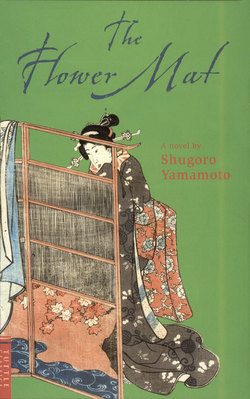

Shugoro Yamamoto (1903-1967) was a man of our century. To read his novel, The Flower Mat , however, is to be plunged back into a time when East and West were indeed two completely different worlds. In the West it was the decade of the 1760s. In Japan, where the events related in the novel take place, it was approximately the 165th year of the Tokugawa period, very early in the seven-year reign of the Empress Go-Sakuramachi at the imperial capital of Kyoto.

More important, however, the tenth Tokugawa shogun, Ieharu, was now ruling throughout the land. The early shoguns had been generals and military deputies of the emperor. But since the Tokugawa family had come to power in 1603, the shogunate had gradually developed into a hereditary office that became the center of power in Japan, surpassing in authority the emperor himself. Under the rule of the Tokugawa shoguns the old social and political organization of Japan was molded into a unified and efficient state.

Not even the power of the Tokugawa shoguns, however, was able to prevent the gradual development of Japanese society, starting around the middle of the eighteenth century, along lines that were finally (in 1868) to lead to the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and the beginning of the Meiji era. The old feudal, ''natural" economic system was gone, having been replaced by a money economy which would weaken the economic strength of the samurai, the ruling social class, and bring about the breakdown of the earlier, rigid class hierarchies.

The samurai had originally been warrior-farmers. Gradually, however, the samurai had ceased to be farmers and had tended to settle permanently in the castle towns, where they frequently found employment as administrators in the local government.

The Flower Mat relates the events of one year in the life of just such a samurai family, the Kugatas, when they become entangled in the intrigues surrounding the adoption of an heir to succeed the ruling daimyo. The latter is in this case one of the daimyo, or lords, of what was then known as Mino Province and is today Gifu Prefecture near Nagoya in central Honshu.

The tale of the reversals and ultimate vindication of the Kugata family is as timeless and universal as the human race itself. But the social structure and the background of feeling and philosophy which are so successfully portrayed in The Flower Mat are peculiar to Japan—perhaps even peculiar to the Japan of an earlier age.

Here we find ourselves in a family-oriented society in which the whole is greater than any of its individual components, a society whose members are motivated almost exclusively by a sense of duty—duty to family, to clan, to ruler, to a spiritual ideal higher than that of personal fulfillment. The needs of the individual are completely subordinate to those of the larger world of which he is a part.

Ichi, the instrument of the Kugata family's salvation, appears as the ideal Japanese woman of that time. She exists, and is valued, not for herself as an individual but as a loyal wife completely devoted to her husband and his family. Affection, whether between two people of opposite sex or between members of the family, is expressed not in terms of feeling or passion (no matter how highly spiritualized) but as a matter of supreme kindness, courtesy, and devotion to others' welfare.

The Western reader looks in vain, then, for traces of the conflicts and passions that dominate Western literature. At first their absence may puzzle and disconcert him. By the time he reaches the end of The Flower Mat, however, he experiences a strange feeling akin to solace and assuagement. There is something curiously soothing in this vision of a world motivated by quiet affection and devotion to simple, spiritual values rather than strong physical drives, material desires, and the urge for individual fulfillment.

—THE TRANSLATORS