Читать книгу Zen Garden Design - Shunmyo Masuno - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

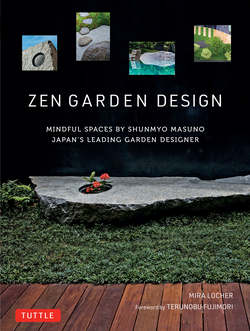

ОглавлениеTHE COMPLEXITY OF ZEN GARDENS

FOREWORD BY TERUNOBU FUJIMORI

In Japan there are gardens made only of gravel and rocks, called sekitei, or rock gardens, which came to the attention of the world in the latter half of the twentieth century. However, given Japan’s long history of gardens, other types of unique gardens have existed for a very much longer time.

The first true garden form that came into existence in Japan originated from the initial Buddhist culture that entered Japan from continental Asia in the sixth century, during the Asuka period (c. 552–710). Regarding religion, the garden came into existence as a combination of Buddhism mixed into Taoism, following traditional Chinese religious practice. To be specific, the main feature was the creation of an island within a pond. The pond represented the ocean, and the island symbolized Mount Hōrai in China (the mountain of Eight Immortals in Chinese mythology). It is said that within Mount Hōrai live hermits who make elixirs that, when imbibed, impart immortality.

Mount Hōrai-style gardens with their groupings of ponds and islands continued for a long time, from the latter half of the Nara period (710–794) until the Heian period (794–1185), when the style transformed considerably, and Jōdo (Pure Land)-style gardens came into existence. This style was the result of significant changes in religion in Japan. The role of Buddhism shifted from protecting the country to a focus on individual salvation. The political regime changed, with aristocrats substantially seizing power in place of the emperor. And rather than the old teachings of Buddhism, which expressed anxiety at the arrival of Mappō, or the age of decadence and degeneration of Buddha’s law after death, people placed their trust in Amitabha (Amida Buddha, the principle Buddha in Pure Land Buddhism) and sincerely wished to die peacefully in the Western Pure Land of Amitabha. In Buddhist history, this ideology is known as Jōdoshū, or Pure Land Buddhism.

In order to express this ardent wish, a statue of Amitabha, resplendent with gold color, was erected with a garden in the image of the Pure Land created around it. Specifically, a pond replete with formal variation was constructed and represented the ocean, with the pond’s edge acting as the sandy beach. A pine tree was planted on a large island in the pond, with the gold-colored Amitabha statue placed in a glittering vermilion and gold enshrinement hall. From the shoreline, the statue could be approached by crossing an arched taikobashi bridge.

Without question, we understand this Jōdo-style garden originating from the Pure Land Buddhism established in the Heian period as the foundation of Japanese gardens that continue until the present day. Now, most Japanese-style gardens with this exquisite combination of water, greenery, and rocks, which foreigners visiting Japan so admire, are gardens evolving from this format.

I believe we can recognize two characteristics as the basis of this construction we know as gardens. First is a spiritual heaven in the form of paradise (Amitabha’s Pure Land), and the other is a miniaturization of the country as a garden. A fundamental quality of Jōdo-style gardens is the abundantly green chain of islands within the ocean in the shape of the Japanese archipelago. However, in the Kamakura period (1185–1333), which followed the Heian period, a garden that competed with this Jōdo-style garden suddenly appeared. This is the sekitei, or rock garden. The background of the appearance of the sekitei stems from a shift of political power away from the aristocracy that gave way to the rise of the samurai warrior class and, in terms of religion, the emergence of Zen Buddhism.

For samurai, the comprehension of the potential of going to battle and facing death every day inevitability resulted in deep introspection about their own personal existence. Hence, the resplendence of Pure Land Buddhism’s sculptures and gardens was not suitable. The Buddhist practice that samurai followed was Zen Buddhism. Zen partly places emphasis on looking hard introspectively at the essence of things and staying aloof from dazzling ornamentation and worldly possessions. In place of that, nothing was regarded as more important for religious training than zazen Zen meditation.

Bodhidharma, the Indian founder of Zen Buddhism, sat in self-reflection facing a rock deep within a cave for nine years and finally attained the state of enlightenment. From there the manifestation of a rock as the symbol of Zen Buddhism emerged. This idea passed through China and was transmitted to Japan. Zen priests began to create gardens focused on rocks in Zen temples, and in time fine gardens like the rock garden at Ryōanji came into being. Presently, the person continuing that tradition is none other than Shunmyo Masuno.

Reflecting on Masuno’s gardens, firstly what is important is that he is a Zen priest. Formerly, Zen Buddhist priests sat in meditation facing rock gardens in silent contemplation and introspection. In present-day Zen Buddhism, I think that sitting in zazen facing a garden is rare. Paying a visit to the gardens of Zuisenji in Kamakura and Kokeisan Eihouji in Tajimi, created by Muso Soseki (1275–1351), who became known with the establishment of Zen Buddhist rock gardens, we find that sitting in meditation in a cave facing a wall, as well as sitting in silent contemplation facing a huge boulder persists. However, despite the ascetic act of facing a rock dying out, Masuno still undertakes that type of training. Even after having had that kind of experience, to live in the present as a Zen priest, escaping from various worldly desires, is next to impossible. Therefore, of the 108 worldly desires in Buddhism, certainly a few have been abandoned.

Even now some rock gardens are designed by gardeners, but there is a great difference in style between those gardens and Masuno’s. Compared with many rock gardens following the style of traditional rock gardens, if we look at Masuno’s gardens the form of each rock and the arrangement of the rocks possesses a modern sensibility. Because they include this modern sense, the gardens fit well with contemporary buildings, and both natural rocks and quarried rocks split with a chisel can be utilized. Previously, Isamu Noguchi’s goal for his modern sculpture was based on his own particular sculpting method of splitting or cutting only one part of a natural rock. Masuno’s gardens also belong to that lineage.

In Zen, the final obstacle is transcending self-consciousness, and as an ever-developing Zen priest, Masuno’s next theme certainly will be found within that realm.