Читать книгу Tennis Method - Defined Timing - Siegfried Rudel - Страница 6

ОглавлениеI. METHOD -

DEFINED TIMING

PRESENTATION OF THE PROBLEM

A tennis teacher stands in front af his pupils and shows them the movement of a stroke. He wants to give them a very detailed demonstration of the movement and performs it very slowly. After this he asks his pupils to imitate the demonstrated movement. The pupils try to do this, the teacher corrects their movements, and after some repetitions the pupils' movements correspond with the teacher's idea. This is an everyday situation, and it is typical of tennis instruction. The learning process seems to be unproblematic since, after a short period of practice, the pupils' movements resemble the movement form demonstrated by the teacher.

After this, the teacher places himself opposite his pupils on the other side of the net and hits the ball to each of them; they are asked to return the ball. The first pupil remembers the movement demonstrated by the teacher well and performs it correctly with the intention to return the ball. However, he misses the ball. "Your movement is correct, but don't forget to hit the ball", is the teacher's comment.

A ball is then hit to the second pupil. He has listened to the teacher's correction and therefore tries to hit the ball at all events. He succeeds in hitting the bali, but the movement form which he practised only a short time ago is hardly recognizable."You hit the ball, but your movement is not correct. Have you forgotten for example the sideways stance?" the teacher asks in order to draw the pupil's attention to one of the movement phases demonstrated by him.

The third pupil now tries to perform the sideways stance, but he hits the ball only with the frame of his racket. The ball disappears behind the fence."Concentrate on hitting correctly! Focus Your eyes on the ball!" And so it goes on. If the pupils perform the movement as it was demonstrated by the teacher, they do not hit the ball; if they hit the ball, their movement form is not correct. Both teacher and pupils are at a loss.

Finally, the pupils do not know anymore which of the teacher's instructions they should follow because everything they do is wrong. The teacher is helpless because none of his advice results in the pupils returning the ball correctly. Is this only a little unimportant tennis story or is there more sense in it?

The dilemma which expresses itself in this interaction between teacher and pupils is the core of a problem which scientists, or better, those with a certain way of looking at science are confronted with. The tennis teacher who demonstrates a movement to his pupils and simultaneously explains it in detail is a phenograph; i.e., he explains the outward picture of the movement as if it were a moving photograph, e.g. the moving arm, the trunk, the knees, etc. In research, too, people try to solve the movement problem by highly exact measurement procedures, by analysing only individual parts of human beings. These investigations are even extended to the nervous system. But even electroencephalographic measurements are basically nothing more than a phenographic way of looking at things, which is an attempt to salve the problem with tape measure and slide-rule, by constantly introducing new parameters and with technical aids.

It is, however, forgotten that every human movement has a meaning. Or, as in the example given above, the teacher succinctly says: "Concentrate on hitting the ball correctly!" However, hitting the ball correctly really consitutes the meaning of the movement. Why is it that the tennis teacher suddenly refers to the hitting, the aim, i.e. the meaning of the movement whereas he usually applies a teaching method which is only oriented to the outward movement? "Concentrate on hitting the ball correctly!" By this statement, the tennis teacher approaches the core of the problem, but his teaching method is not oriented towards this goal. Rather, he considers hitting the ball correctly and mastering it so that it can be played to a point chosen in advance as unimportant or as a matter of course. Only after all instructions have failed is the meaning of the movement considered. Perhaps this example can make clear that there is a discrepancy between the presentation (description) of a movement form and its meaning, which is inherent in this form.

The way of looking at human behaviour whose aim it is to objectivate man is meaning-less! However, to postulate this meaning and to connect it with the movement form must be the very objective of a movement theory which does more justice to man! If movement forms are represented by recording the trace of a body point in a photograph by means of long-term exposure, it is useless if afterwards this trace is measured with all kinds of aids. The objective must be to give a meaning to his trace, to ask for the cause of its coming into existence and in doing so to understand the meaning of this very movement form.

1. DEFINED TIMING: THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

So, the starting point is the meaning of the movement, i.e. hitting the ball correctly, and on this basis it will be attempted to approach the form of the movement. Who or what hits the ball? The racket face hits the ball and not the player's body. If the racket face shall hit the ball, what is meant by hitting it correctly? The ball is hit correctly if it is played to a place chosen in advance. 'Placing' is therefore the optimum result of the meeting of racket face and ball.

This way of asking makes clear what compulsion the movement form is subjected to. The compulsion of hitting the ball with the racket face admits the idea of reducing the movement form to the form of the movement of the racket face in order to be able to examine it better. Under the condition that the ball shall be hit to a certain place, the racket face must perform a compulsive movement in relation to the ball. In doing so, it is the task of the player's body to make possible this compulsive movement, This restricts the body's freedom of movement; but in spite of this, the movement possibilities are immense.

The relationship between racket face and ball, however, restricts the movement of the racket face to a certain form, just as if the racket face were put into a guiding machine (ball behaviour). The player must move in such a way that this 'act of being guided' is not disturbed. This process allows for a multitude of movement possibilities which can only be described as ´Gestalt´. Under the conditions mentioned above, the movement form of the racket represents the player's performance in relation to the moving ball. There must be a relation between the movement of the racket face and the movement of the ball, i.e., the question about the movement form is the question about the relationship existing between the ball which must be perceived by the player and the racket face.

It corresponds with the demand already made by V.v. WEIZSÄCKER (1973, 176): "... then our question is not anymore how spatial relationships can be perceived, but the question rather is: What relationship between the ego and the environment is created by perception?"

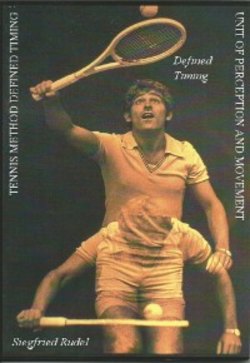

Figure 1: The ball as the object of perception