Читать книгу Searching for Simphiwe - Sifiso Mzobe - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

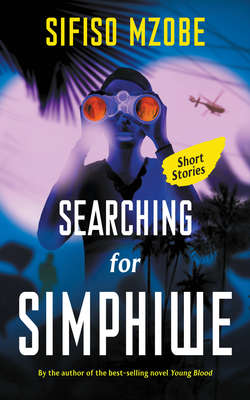

Searching for Simphiwe

ОглавлениеThe knock on our kitchen door did not scream of urgency, but I suspected it had something to do with my brother, Simphiwe. I shared a room with him: my fifteen-year-old, troublemaker of a brother. In a descent too fast – only three months – he went from being a child of great promise to an out-and-out lost one. I curse the day he started smoking wunga. That poison turned him into a neighbourhood thief.

I fought for his honour when the very first allegations of him stealing clothes from washing lines surfaced, only to find he really was the thief. I slapped him when he stole and sold my cellphone. I lost control, and decked him, when he pinched cash from Ma’s purse. Then I had to recoup our household appliances from the wunga merchant – all sold to him by Simphiwe.

‘Khulekani, someone’s here for you,’ Ma called out.

I didn’t answer. I had just noticed that next to my flip-flops, the box with my new sneakers was empty. I imagined the foul things, in dirty places, that Simphiwe was stepping on with my new sneakers; saw visions of him high after he sold them for a wunga hit.

Before he became a wunga boy, we shared some of my older T-shirts. When Ma forced us to go to church, I let him choose from my smarter clothes. But Simphiwe stopped loving himself after he inhaled that first drag of wunga. His side of the room became untidy, his bed never made.

‘Simphiwe needs a klap,’ I said to the mirror, before finally responding to my mother’s call.

I walked out to see scrawny Boy Boy, another wunga slave, waiting outside the front door.

‘I was just checking on Simphiwe,’ he told me. ‘I heard he was in a fight at the wunga spot. Is he here?’ Boy Boy couldn’t look me straight in the eye. He scratched the back of his head, arms and shoulders – tell-tale signs that he yearned for a wunga hit.

‘You know I don’t entertain his nonsense. It has nothing to do with me. It’s his life, not mine. He is not here.’

I was going to close the door, but he went on.

‘I thought, as his older brother, you should know about the fight,’ he said, his scratching growing vigorous.

‘What’s wrong with you?’ I asked.

‘I need a hit. Do you have R5, Khulekani? Please, I want to buy bread.’

‘You just told me you need a hit, Boy Boy.’

He got my drift, understood he was not going to get a cent out of me. I fumed at Simphiwe’s latest stunt, my vanished sneakers, and the dead gaze in Boy Boy’s eyes. It all added to the hangover I already had. I wanted to complain to Ma but when I opened the door to her bedroom, I found she had gone back to sleep. I glanced at the clock on the wall. It was still only six in the morning.

I drank water and napped the hangover off, waking up to a silhouette at my door an hour later. It was Ma.

‘You know I’ve never dreamed of your father since he passed, but I just saw him now in my dreams. He told me Simphiwe is in trouble.’

‘Simphiwe does this every weekend. He’ll be back. Besides, Ma, I have tests this week. I need to study.’ During the week I crashed with friends on campus since Simphiwe’s antics were not good for my studying, but over weekends I had to come back home to Ma and the troublemaker. Luckily I was still on course to finish my Tourism diploma on time.

‘Shut up and listen to me.’ Pools of tears filled Ma’s eyes and she went on: ‘Your father said Simphiwe is in trouble and you must look for him. And that is exactly what you are going to do.’

‘Okay, okay, Ma!’ I was alarmed by what Ma had said, and how she said it – her voice stern, before she broke down in tears. I left the house to show her I was going to do as she asked, so that she could calm down. I was worried about the state she was in, but not about Simphiwe. He had been going AWOL over weekends regularly, so to me it really was just more of the same.

The change in my little brother’s life had happened at high speed. It was painful to witness: the lies, the stealing, the shame he brought to the family. My dad, especially, must be turning in his grave.

I tore open a new airtime voucher and thought angrily of my sneakers – brand new and two sizes too big for Simphiwe. It took me a long time to make enough money to buy them, working as a busboy in a restaurant after my classes at Tech.

Cold bottled water from the shop on the corner lifted the weight from a heavy night of partying. Blocking thoughts of Simphiwe, I decided to rather call Anele, this beauty in my class, to hear how her studying was going. If anyone could motivate me to hit the books hard this weekend, it would be her.

While punching in the voucher PIN, I made out the scrawny frame of Boy Boy with another wunga addict on the outskirts of my peripheral vision. They walked, lost. When they saw me and approached, I recognised the need for a fix in their eyes.

‘Have you seen Simphiwe yet?’

‘No.’

‘Eish!’ Boy Boy whined and clutched the back of his head.

‘What’s wrong, Boy Boy?’

‘I haven’t had a hit today. Help me out; the pain in my belly is unbearable. I can feel my intestines twist into knots. The back of my head is cold, my whole body itches. Please, Khulekani, I’m only short by R5. I beg you, please, my brother. I am good for it. We have this roof-painting job, but we can’t function without the hit. I’ll pay you back this afternoon.’

‘I would, Boy Boy, but you are not helping me with Simphiwe. I bet you know where he is, but you are covering for him.’

‘No such thing. He has not been smoking with us for a week. Look for him at the wunga merchant,’ Boy Boy said, scratching harder, almost peeling the brown off his skin.

‘What’s his name? Skhumbuzo?’

‘Not Skhumbuzo. Bheka, in the shacks. That’s where Simphiwe smokes now, where I heard the fight happened.’

Boy Boy gave me the directions to the shack and again pleaded most sincerely for cash. He looked to be in physical pain, so I relented and gave him R5.

Before I could call Anele or go look for my brother at the wunga merchant, a friend called: ‘We are around the corner to pick you up.’

One beer to kill the hangover led to a drinking spree that put the Simphiwe problem on the back burner and ended with me sneaking into the house in the early hours of Sunday morning.

I thought Simphiwe would be in our room when I woke up; thought he would be asleep fully dressed and snoring as usual, his socks stinking up the room. I was so convinced that his thin self was concealed in the bedding that I called out – to nothing. I also thought I’d wake up to Ma away from home and at church as always on a Sunday, but she was in the lounge on the sofa, her eyes red with worry.

‘Ma, did he return?’

‘No, he didn’t. Did you not find him yesterday?’

‘No, Ma.’

‘He is worrying me.’

‘Don’t worry. He probably lost track of days – the wunga he smokes does that. Are you not going to church today?’

‘No, we will visit the sickly instead.’

‘I heard he was seen at the wunga merchant in the shacks on Friday. I’ll look for him later.’

‘You could have done that yesterday. What’s wrong with you?’ Ma asked.

‘It was late when I heard the news. I could not risk going there at night with the muggings in the neighbourhood.’

‘What’s holding you back from going there now? Alcohol steams off you with every answer. That child is watching you, that’s why he is this loose!’

‘I don’t smoke wunga and Simphiwe doesn’t drink,’ I retorted.

‘That’s all you know? To answer me back?’ She was mad.

‘What did I do, Ma? Every time Simphiwe does wrong, you blame me.’

A taxi stopped at the gate.

‘We’ll continue this when I come back,’ she snapped, closing the front door.

Through the lounge window I watched Ma get into the taxi. For the first time that weekend she smiled as she greeted her friends from church. Then she settled in her seat and just as quickly was again casting a sullen gaze out the window as the taxi drove off.

With Ma attending to her church stuff, and Simphiwe out there chasing, Sunday mornings were perfect for studying. Ordinarily I was efficient in the silence. I’d planned to study for the last tests of the semester coming up in the week, but on that Sunday thoughts of Simphiwe crammed every cube of the empty space.

My books were open on my lap, but I stared out of the window, looking at nothing. When I looked back into the room it was to our wall unit with Simphiwe’s trophies for running and karate. His school picture showed him beaming – a smile I had not seen in months. I tried to study, but thoughts of Simphiwe darted through my mind.

I tried to nap, but couldn’t take my eyes off his drawing on the wall of our bedroom. On a sheet of white A4 paper Simphiwe had sketched a lake, using two shades of pencils. I was so deep in the drawing that the lake seemed to ripple and shimmer.

When I came back to reality, I walked to the kitchen, opened the door and went out looking for my brother.

I had not been to the shacks in two years and was surprised by how much the community had grown in such a short time. Boy Boy’s directions were spot on: I saw it from the top of the hill, the neat shack at the bottom of a long, winding road.

Sunday morning unravelled as I made my way down. A young mother hung the last of her infant’s clothes up on a line. An old woman tossed water from a bucket onto the pathway just after I passed her shack. I walked faster to avoid the stream of soapy water. I recognised a few faces from high school.

Unlike most other shacks made of timber and metal roof sheets, Bheka’s was built properly with concrete blocks and roof tiles. Straws with the poison – wunga – were in his overall pockets. I watched as he made a sale to two boys about my brother’s age. Young slaves to the first high, they were their families’ Simphiwe.

‘Your brother exchanged his cellphone for a lot of wunga. He took his SIM card with him,’ the wunga merchant said when I asked about Simphiwe. ‘I don’t know where he went because it gets busy here on weekends, but he was here. He started a fight. It wasn’t in my yard; it was down there at the cul-de-sac. Tell the boy to cool it. He’s still young and the things that come out of his mouth are too old for him.’

I sat on the steps and smoked a cigarette, my mind processing the information about my brother. A wunga boy stopped and shook my hand like he knew me. It took me a while to recognise him. As he let go of my hand, I realised it was a friend’s brother. He had grown unhealthily thin. After greeting, I asked if he had seen Simphiwe.

‘He was here on Friday with Dumisani. There was a fight. Dumisani started the whole thing. Simphiwe was fighting for him. Wunga hits us in different ways. For most of us it zaps energy, but Simphiwe gains energy. He is everywhere: dice game, cards … Your brother doesn’t know when to stop. And he never backs down. We broke up the fight but Simphiwe just kept pushing it. It’s his karate that makes him think he is invincible. It’s worse since he became friends with Dumisani. Your brother uses Dumisani’s reputation as a shield, but the boy whose nose he broke is just as bad, if not worse.’

‘Dumisani who?’

‘You know him, he lives near the butchery. You went to school with his brother, Sango.’

‘You mean that fat boy?’

‘He is thin now, after what happened last year and his time away. You know what happened, right?’

‘Yes, I know.’

‘Anyway, they left here in a friend’s car. I don’t know who. Sorry, I’m in a hurry. Good to see you. You have R5 for me? I need to get my day going.’

I don’t remember if I gave him the money or not. Not much registered besides the bolt of shock going through my body as I connected the name to a face. Dumisani was Sango’s younger brother: the killer kid.

I wanted to buy thin-cut T-bone from the butchery – a little contribution to the household from tips I made during the week. The only butchery with decent meat was near Sango’s house anyway. I’d pass by and ask about Dumisani’s whereabouts.

I buzzed at the gate and waited, until the neighbour opposite, an old lady, called out from her veranda: ‘There’s nobody there. They are away at a church conference. Try them tomorrow.’

‘What about Sango? Is he around?’

‘Sango works in Richard’s Bay now, since the beginning of the year.’

‘And his younger brother, Dumisani?’

‘Who am I answering to? My boy, who are you?’

‘Apologies for not introducing myself. I went to school with Sango and my name is Khulekani.’

‘I see. I haven’t seen Dumisani since Friday morning when he left the house keys with me.’

‘Do you have his phone number?’

‘He doesn’t have a phone. He is a wunga addict. His parents got fed up because every time they buy him a new phone, he sells it to smoke that poison.’

I thanked her, smiled politely, and said goodbye when she started down the road to chatty. I dialled Simphiwe’s number three times on the way home, wishing that, by some miracle, he’d paid the wunga merchant and got his phone back while I was out looking for him. All I got was his voicemail.

Ma had just finished cooking Sunday supper when I got home. I told her the story but thought it best to leave out all the added madness that had come into Simphiwe’s life. The fact that she knew he’d become a wunga addict was bad enough, without me turning the screws. She did not need to hear about his fights and camaraderie with killer kids.

‘They left in a friend’s car. My guess is they went to the city. There were parties all over, this weekend. I checked at one of his friend’s houses, the one they told me he was with. A neighbour told me the family was away. I’ll check in the morning.’

A very thin layer of worry lifted from her face. Nonetheless, it was a grim Sunday. I did not eat. The house was filled with the delicious smells of Sunday supper, but I felt sick.

Later, I fell asleep on my books, but then woke with a jolt due to a nightmare in which a green Golf was going up in flames.

By my first class at Tech, Tourism Policy, the bad dream had been forgotten, as nightmares and even happy dreams often are. I was supposed to study past test papers for the rest of the day, but the weight of the weekend won. I squeezed in a few hours of rest in a friend’s room while he was in Technical Drawing class.

I stared at the ceiling for a while, but then fell into a deep sleep polluted with bad dreams that went on and on, and chilled my bones. Nightmares about Simphiwe, or rather his voice, for he was out of focus and far away. There was no background either; just a thick blackness and his voice: loud, complaining, accusing …

‘Of all people, Khulekani, I thought you would find me. Do you know how cold it is here? When you come here, bring my jacket!’ he shouted.

‘Which jacket?’

‘That blue Nike one, with the white tick.’

‘But you sold it for straws of wunga.’

‘Just bring me a jacket. It is cold here.’

His voice faded away.

I bolted upright, soaked in sweat. I grabbed my backpack and went down to the road to hail a taxi to Umlazi township.

The taxi dropped me off at the butchery near Sango’s house. I made my way to the neat house with the lush, trimmed lawn. Sango’s parents, both teachers, had lived in this house for a lifetime. When we were still in school, especially primary school, Sango would come and play soccer at our section, in our yards, but we never played at his house. Their grass was too manicured for our kick-abouts.

They raised Sango right. Connections got him a dream job when he left high school. He married his girlfriend from church and babies would surely be on the way soon. He had probably been promoted too, as he was now working in Richard’s Bay. His was a life prescribed, and he aced it with flying colours. Sango the genuine good son – yes, they succeeded in raising him right. It was with their youngest son, Dumisani, that they achieved the opposite. From a crybaby, Dumisani grew to be general bad news: high-school dropout, addict, killer kid.

Sango’s parents’ dining room could pass for a shrine to Christianity. The face of the clock on their wall was a solemn, gazing Jesus Christ. There was a print of a blue-eyed Virgin Mary and one of Joseph and Mary staring at baby Jesus. Nordic, of course – all their halos bright and gold like the colour of the hair on their heads. And JC again, this time on a cross carved out of wood. In the mix, away from this centrepiece, there was a photo of Sango and Dumisani with their parents – dignified folk in their Sunday best. Peace brimming in everyone’s eyes, except Dumisani’s. There was something that looked to me like confused evil in his stare.

Sango’s parents welcomed me warmly, with a genuine goodness of manner that made it hard to understand how they had given birth to a killer.

‘How can we help you, my boy?’ the father, Mr Mlaba, asked.

‘My name is Khulekani and I’m a schoolmate of Sango’s. I’m looking for my brother, Simphiwe. He was last seen with Dumisani. I was wondering if he could tell me where Simphiwe is?’

As he answered, a deep, silent pain surfaced and settled in his eyes. ‘We last saw Dumisani on Friday when we left for the conference. These kids, they are not back even today and Dumisani is still supposed to be signing. If his parole officer gets here to find him absent, there’ll be trouble. I’ve never seen a person care less than my boy.’

‘We have the same problem at home.’

‘Where have you heard of a sixteen-year-old gone for the whole weekend? Who knows what evil they are doing? They don’t go to church. They don’t believe in the Saviour. A life without the fear of God is not a good life.’ His eyes shifted to my backpack and he asked, ‘Are you coming from school?’

‘Yes, I’m at Mangosuthu University of Technology.’

‘What course are you studying there?’

‘Tourism.’

‘That’s the way, my boy. There are no shortcuts to a better life. You must have education and faith. Where do you praise?’

‘Catholic.’

‘That’s very good. Keep it like that. You can never go wrong with education in your mind and Jesus in your heart. Leave your number. I’ll get him to call you when he gets back.’

‘I’d greatly appreciate that.’

‘Mama, please get my diary.’

I noticed that Mr Mlaba had the latest cellphone, but he still believed in writing numbers in his diary. I saved his number on my phone while he heaved to get up and buzz me out into a wintry, silvery-orange setting sun.

Simphiwe was still not back in our room. But I told myself that he would be back the next day. Simphiwe never came back later than Tuesday after disappearing over a weekend. He would show up, high out of his mind, and exhausted. He would sleep until Wednesday afternoon. When he woke up, I could recognise parts of his pre-wunga self, before the drug took hold. But by that evening the craving would call him back and he would be gone.

In the few clean hours he had, he used to take out his pencils and draw, or read a magazine. The day he picked up the wunga habit, Simphiwe stopped drawing things from nature. Instead, he drew only self-portraits again and again. The first portrait was detailed and impressive. He had expressed his character on paper. But, as the moments of sobriety became scarce, so his portraits lost their detail.

I sprawled Simphiwe’s art over his unmade bed, and realised that since the drugs started he had never finished a drawing. He began afresh on new paper after only sketching a few details of his face. The portraits started missing ears, then hair, chin, mouth, nose, eyes, until the last drawing was just an outline of his head. He had drawn his own disappearance into drugs.

Ma and I watched TV and talked about the news, the weather, and the good Simphiwe of the past, the Simphiwe who was still a child in our eyes. I consoled Ma, told her he would return and draw beautifully again. The conversation turned to Sango and his perfect life, and then to how expensive my education was, and ended with us grumbling about how the price of cooking oil had rocketed.

On Tuesday I wrote and, frankly, aced the test. Afterwards I sat in the quad and smoked a cigarette that made me dizzy by the third drag. Then, while downing a Red Bull, I saw her, the beautiful Anele, my friend who was steadily stepping away from the friend zone. She waved and walked over.

Tall, spindly, a high jumper in high school, with a face that deserved to be on a magazine cover. While next to her in class, or working on assignments in the library, the pull between us was magnetic. Every time I leaned into Anele, I inhaled strawberries and my insides twisted. I had told her how I felt. She’d smiled and doubted, but slowly she was warming to the idea.

Now she laid her heavenly eyes on me. I felt the warmth of her concern when she rested her hand on my back.

‘Are you okay? You seem down,’ she said.

My worries obviously showed. I told her Simphiwe’s story on a walk around campus.

‘My cousin is also on that wunga,’ she said. ‘You leave nothing within reach of that dude. At the height of his madness he stole a pot while it was cooking Sunday chicken curry and sold it with the curry!’

My enamoured eyes were all over her for the whole fifteen-minute walk. We were already at the door to her room.

Whenever I was with Anele, my burdens disappeared. Even Simphiwe was forgotten in that walk, if only for a while.

‘You must eat something,’ she insisted, when we were in her room. She sliced bread and cheese. I bit into the sandwich she offered me but struggled to swallow.

‘I have to return these books due today. I’ll be back in thirty minutes, and we’ll work on the paper then,’ she said.

I worked on the test paper while she was at the library. This was part of my charm offensive: she’d return to a man with all the answers. I was done in twenty minutes.

I did my best to quell drowsiness. I went out to the garden and smoked a cigarette, paced about the room, snooped, opened her photo album, lay on my back on her bed and paged through her celebrity gossip magazines. The softness of her fragrant bedding won. I napped.

I woke to a soft strawberry warmth in my arms – Anele, up close at last. Outside her window the day had gone, the afternoon shaded by the setting sun. I looked into her eyes and my arms circled tightly around her waist, pulling her even closer. We were both fully clothed, but I was aware of every inch of her. Sparks in our eyes set off a series of time-stopping smooches. I was lost in our kisses. The electricity between us rose to a high voltage.

She stopped.

‘You can answer that, you know,’ she said.

I had not heard my phone ringing. There was a missed call from Sango’s father. I ignored it and got back to kissing, but he was persistent and my phone rang twice more. At this perfect moment to seal the Anele deal, I took a call I had to take.

‘They were beaten by people in Claremont for housebreaking. Blood-curdling mob justice,’ Mr Mlaba said, distressed, when I finally answered. ‘Your brother escaped earlier on in the beating. My son Dumisani … he was beaten badly. He was close to death when the police arrived. A case has been opened against Dumisani and Simphiwe. The police are looking for your brother – perhaps they will find him. We are with Dumisani at Westville Hospital. He’s unconscious but stable. The doctors told me there’s heroin and Jik and rat poison in his blood. This wunga of theirs drives them crazy.’ The phone line was crackly and I struggled to hear.

I did not believe what I thought I heard. I convinced myself that my mind had made up the words he’d just told me; that maybe the bad phone connection somehow distorted his speech. I called him right back and Mr Mlaba told it exactly as he had done a few seconds earlier.

On the taxi ride home I worked out many ways of telling Ma, but when I saw again how uncertainty pained her, I told it as bare and gritty as Mr Mlaba had told me. She called him immediately, and broke down when she heard it first-hand.

As her sobs pierced the walls of our home all through the night, I whispered angry questions and a prayer into the darkness of my bedroom.

Why is Simphiwe this lost? Why did he inhale that first wunga drag? Why did I have to witness my mother breaking down? Why did my father die and leave us? Where are you, little brother? Please, God, keep him out of harm’s way, wherever he is.

We were at the taxi stop earlier than the township’s earliest risers. Ma looked far away into the distance; my thoughts were sombre. As we stood in the cold darkness in silence, I had a feeling of déjà vu – this had happened before. I felt exactly like I did that morning my father slipped into a coma and we had to catch the first taxi of the day – part angry, part sad, and really scared. It had been chilly and dark, just like this.

Claremont Police Station was packed, so we only found seating at the edges of the charge office benches. The service was slow, the long queue served by just one officer. And the young constable was unable to multitask. Numerous times I saw him stop certifying a copy to make a leisurely comment on conversations with his colleagues. He had the stamp in mid-air for close to a minute while he yapped.

There were a lot of mothers in the queue. Ma quickly exchanged stories with the woman next to her. This lady was immersed in shock because her son stabbed an old family friend dead. She told her story with sad resignation. ‘Our children,’ they both lamented.

Ma turned to me. She asked, ‘Are you not hungry?’

Her scones appealed to me, but I couldn’t eat once I had seen the gash on a man’s head, further up our bench. The wound was right at the top of his skull, not long, but deep and in need of stitches. It seemed to have a pulse, like there was a tiny heart beating just under it.

‘He crept up on me, hit me with a golf club. I had done nothing! I was just drunk and walking by,’ he told people who asked.

‘No, Ma. I’m not hungry,’ I said, looking away from the gash.

In the three hours we were there, Claremont Police Station continued to malfunction. But it was our turn, eventually. I explained our story.

‘The detective is not in. He’ll be in tomorrow,’ said the young constable.

‘After waiting for so long we can’t get help?’ I couldn’t believe it. ‘Don’t you know anything about the housebreaking case against my brother?’

‘No. The proper person to talk to is the detective in charge of that case.’

‘Are you serious? You mean in this whole place there’s no-one else who can help us?’

‘The detective will be in on the night shift. I’ll give you his office number. Call him and set up an appointment.’

‘Are you serious? This is a joke!’

The group of police officers beyond the counter, who were slacking at their jobs, turned to witness my tantrum.

‘If you paid as much attention to your cases, they’d be solved!’ I vented.

‘Shut your mouth! Go outside and wait by the gate,’ Ma shushed me.

I stormed out of there, irritated. In a glance back I saw that Ma had her hands together as she pleaded with them. Our constable, plus two female constables from the slacking gang, now listened to her.

She joined me outside a while later, shaking her head. As we were waiting for a taxi, one of the young female constables called out to us. She ran up and stopped next to Ma.

‘Here is Detective Shange’s cellphone number. Phone him in the afternoon because he only knocked off this morning. And tell your son to stop being so rude.’

In the taxi that took us home I tried the number three times and got voicemail each time. When we arrived home, Aunt Busi was waiting by the gate. She hugged Ma and put her arm around my shoulders. In the lounge they wallowed in maternal sadness.

I went out and did some neighbourhood digging about the driver of the car that Dumisani and Simphiwe had left the wunga merchant’s shack in. I was told it was a green Golf I, the same make, model and colour as the car I had seen burning in my nightmares. I got information from here and there that led me to think that the driver was a certain Sandile.

Sandile was older than both Dumisani and Simphiwe by a few years. He studied land surveying at Durban University of Technology and worked part time on weekends and holidays, a true hustler. His parents had moved to the suburbs, leaving the house in his hands. I’d known him to be a cool guy, one of those people sure to succeed in life. He was wiping down his green Golf I after washing it when I walked up to his house.

He was happy to talk. ‘I know Dumisani from way back, and Simphiwe from karate, but I did not know he was into these things. They told me they had car rims for sale,’ Sandile said.

He took two camping chairs from the boot of his car for us to sit on. I asked for cold water and downed it while he told me how the whole thing went down.

‘It was a smooth, cheap exchange, nice rims too, BBS mesh. I paid them a grand and dropped them off at the wunga merchant. It was there that Dumisani remembered he had money to pick up in Claremont and asked me for a ride. They bought me a six-pack of beers and filled the tank of my car. Off to Claremont we went. It was all smooth at first. Then it just went crazy.’

‘How?’

‘They started with the wunga while we waited for the man with the cash, a taxi owner. They were blitzed by the time he arrived. He let us into his house. Do you know what Dumisani does? He asks for the bathroom and steals an iPhone from one of the bedrooms!’

I downed the cold water, chewed ice, shifted in the camping chair, unsettled by how the story was developing.

‘Dumisani collected the money, then we went to a wunga-smoking den, still in Claremont, where the stolen cellphone was quickly up for sale. They smoked more wunga, I drank my beers. Then they hatched a crazy scheme that would have involved me.

‘We went our separate ways when they decided to burgle a mansion in the vicinity that had its lights off. They thought I hadn’t heard them hatch the plan, but I was right behind them. I knew everything – knew that I was to be the unknowing getaway driver. ‘We’ll send him out for more beer and tell him to park at the gate of the mansion when he returns.’ That is what I heard your brother say. I started my car and left them at that smoking den. I’ll just tell you, Khulekani, your brother changes. He’s quiet, but once he smokes that wunga, Simphiwe begins to speak the language of thieves. That’s the last I saw of them, going to rob that mansion.’

I walked home in the dusk. At least the green Golf I was in perfect condition, not charred like the one in my nightmares. I kept telling myself this, comforting myself all through that sleepless, starless night.

Detective Shange returned my voice messages around four on Thursday morning.

‘I’ve been out since my shift began. I don’t think I will be at the station at all today. Can you meet me in the city? Meet me at the Umbilo Car Licensing Department between eight and ten. I drive a red Toyota Sprinter. Call me when you get there,’ he said.

I was at the licensing department by half past seven. I called him when his car entered the gates. He motioned for me to get in.

‘Do you also work night shift?’ inquired Detective Shange.

‘No. Why do you ask?’

‘You look tired, like you have not slept. Which one is your brother?’

‘The one who escaped the beating.’

‘Dumisani’s reputation preceded him. I knew about a mad, young, handsome killer kid through my friends at Umlazi Police Station. But when we got to the scene, I only saw the harmless child in him begging for his life. He told us everything, you know. Before he passed out, he sang about your brother. But there are things that can be done. We can work the case in a way that will pin everything on Dumisani. Your brother must just lie low. It would be even better if he actually moved away. I’ll search everywhere and won’t find him, even if he is there. I’ll tell the judge he is nowhere to be found… if you get my drift.’

‘He really is lost. We have not heard from him in six days. That’s why we called you. We thought you could shed some light on the case, tell us what really happened,’ I said.

Detective Shange rubbed his bald head and then the side of his face where an old scar was visible. ‘The owner of the house walked in on a burglary in progress. He pulled a gun and walked the two culprits out into the street. The whole neighbourhood quickly converged and doled out mob justice on the boys. Dumisani bore the brunt of it because your brother managed to escape. For sure he is in hiding. But you would not tell me even if you knew where he is. Would you?’

‘Serious, we really don’t know where he is.’

Shange broke into a tired smile. ‘Well, I want to let you know there is an angle we can work in this case. With a bit of cash, of course, a little something for going to the trouble of not finding him. Just R2000 – that’s not much in the bigger scheme of things. Call me when you have what can make this go away.’

I ate an orange at a kiosk by the taxi stop, and shook my head over the offer from Detective Shange – selling Simphiwe’s freedom like that. But right there and then I came to the decision that when Simphiwe returned I would definitely pay the bribe. I would beg and borrow if I had to, as long as I could keep him out of jail.

Sango called.

‘Have Dumisani and Simphiwe gone crazy? Those two chose the darkness when living in the light is so lovely,’ he said.

We reminisced about how bright our ambitions were when we were their age. He told me there was indeed a baby on the way, work was perfect, and gave me brotherly encouragement about my studies.

‘I hear Dumisani was seriously hurt. How is he?’ I asked.

‘Dumisani regained consciousness this morning. He doesn’t know what happened or where he is. How is your brother?’

‘Simphiwe’s story is worse, my friend. We have not heard from him in six days. Ma is going insane with worry.’

‘Now that’s what drives me crazy. They worry our parents who should be enjoying their lives, reaping the rewards of decades of hard work. Instead they wake to calls from police stations and hospitals in the middle of the night.’ He sighed. ‘Listen, Khulekani, the visiting hours at Westville Hospital are from twelve to two. Dumisani is in Ward 4C. Maybe he’ll be able to tell you what happened.’

Beautiful, but, most of all, clean – that was my verdict of Westville Hospital. I waited in the foyer for the lift to take me up to Dumisani’s ward, and inhaled only sterile air, not the dodgy smells of government hospitals.

Had we afforded to take Dad to a hospital as good as Westville Hospital, surely they could have detected the impending stroke that struck and halted his life? He was locked in a coma for four days, then he was gone. We cried our eyes out amid the chaos and pungent smell of a government hospital. If we could have afforded Westville Hospital, Dad might have still been alive and Simphiwe would be on the right path. My father loved him. Simphiwe spent his whole childhood sitting on his lap. He looked so relaxed, so sheltered when Dad was alive.

I asked for Dumisani at the reception of the ward. A light flashed on the electronic board behind the nurse attending to me – a patient in the ward was in need.

‘That’s him, Ward 4C. Follow me,’ she said.

Dumisani had his own room. Through the closed door we heard him loudly crying out. The nurse looked at the shock in my eyes.

‘He wants a painkiller. That’s how the addicts are. Especially the wunga boys. They’re so desensitised to drugs that they need four times the required dose of painkillers. They also like the opiates in it – makes the detox bearable.’

‘Those drops please. I’m dying of pain. Please, nurse, I’m dying here,’ Dumisani moaned in a mumbly, thick voice as we entered.

Both his legs had multiple breaks with a network of wires and screws running lengthwise along them. His left arm was in a cast, his other arm had stitches running down from shoulder to wrist. He was severely disfigured – his head grotesquely swollen, a stitched gash on his forehead. The upper front teeth were missing. A big chunk of his left ear was also severed. I had never seen anything like it before.

‘Please, nurse. Please!’ Dumisani pleaded.

‘I’m fetching it now, don’t worry,’ she said.

I asked Dumisani for his side of the story after she left.

‘I only remember the ride from Umlazi to Claremont and absolutely nothing after that. I did not believe it when they told me what happened. I thought I’d been in a car accident. Those idiots got me good. I was told that rocks broke my legs, a panga sliced my face, a knife my ear, and a hammer broke my fingers.’

His voice got softer as if talking was tiring him out and I scraped the visitor’s chair closer. I could barely look – that close to him the injuries were nastier, bruises everywhere, every inch of exposed skin was black and blue.

The nurse returned and injected something into the IV drip in Dumisani’s arm. Dumisani winced and adjusted back to a comfortable position. That grimace revealed that he had lost most of his bottom teeth as well.

‘They tell me Simphiwe disappeared into thin air,’ he said. ‘That boy has my respect because he has never been in jail, but he plays the part of a crook well. He knows that the number doesn’t shift backwards, it only moves forwards.’

Dumisani went on rambling. Over and above the pain he suffered there seemed to be a sense of pride in the events that led him to that hospital bed. According to the warped crook mentality he picked up in juvenile jail, it was probably a step up. It was just as well that the painkiller took over quickly, because the drivel he was speaking made me want to shut him up. He fell asleep and even then that same careless, proud smirk prevailed. I had to physically restrain my right hand with the left, because the right wanted to strangle the life out of him.

For the next two days we scoured hospitals and drug dens with my Uncle Clive. I hardly slept, surviving on ten-minute naps while we drove around searching. What woke me up each time was what I saw during those naps: Simphiwe with his back to me, then disappearing.

On the afternoon of the second day, I woke from one of those naps to see Uncle Clive looking straight at me. We were at a red traffic light. He kept his eyes on me until the light turned green and we drove off.

‘Khulekani, we must try other means. There are people with gifts out there; we must try traditional healers as well. There is one in Port Shepstone. I hear he is good at finding the lost. I know my sister doesn’t believe in that world, but in the situation we are in we have to try everything. Saved or not saved, we are still African,’ he said.

‘I have been dreaming of him since he disappeared, but more so in the last two days. He has his back to me and disappears when I focus. If the healer can help us find him, we should visit him,’ I said.

‘We have to wake up early tomorrow because Port Shepstone is far. We must be on the road by half past three at the latest.’

After a long silence he added, ‘We have to start searching morgues as well. Better sooner than later.’

That night I switched my cellphone off and cried. I tried to sleep, hoping to find Simphiwe in my dreams. But sleep was elusive, so I stared into the dimness of our room, faintly lit by the streetlight outside. I could see Simphiwe’s drawing, the one of a shimmering lake, come to life. I turned away from his art to the blank wall on my side of the room, shell-shocked that it had finally come to traditional healers and morgues.

I switched my phone on around two in the morning. There were several voice messages from Detective Shange, and one text message from Anele. She was just checking on me. Asked why I had missed the latest test; said working on test papers was no fun without me.

Detective Shange was serious in the voice messages. ‘Call me when you get this,’ all his messages said. I didn’t bother to return his calls. I was in no mood to talk about bribes. I opened the curtain and saw Uncle Clive parked at the gate. I had one of Simphiwe’s T-shirts with me. An item of clothing was necessary in aiding the traditional healer to find him.

While we were driving to Port Shepstone, Detective Shange called repeatedly – first from his cell number, then from his office number. So finally I answered.

‘There is someone at the station you need to see immediately.’ My heart filled my chest with one loud thump as I mistook what he said to mean they had found and arrested Simphiwe. Before I could speak, he proceeded: ‘He says he knows where your brother is.’

‘We’ll be there in twenty minutes. Keep him there,’ I said.

Uncle Clive changed route and stepped on it.

In Shange’s office there was a man in his late fifties. Introductions were made. This serene man was a traditional healer from Eshowe, north of the coast. He was the opposite of the traditional healer stereotype, being clean-shaven, with no beads, no traditional garb, swank trousers and shirt, and his shoes were definitely imported Italian Mauri. Manqele was his name.

I learned later that he was something of a rock star in the world of traditional healing. He made his name during the floods of 1987 when he recovered over thirty drowned bodies. He knew the location, date and time when a corpse would wash up on shore, or resurface bloated and face-down in rivers and lakes. Over the years his gift of finding grew, and he started to find the living. Locating runaways, missing children, and young professionals no longer calling home since they moved to Gauteng made him a mountain of money. He looked at Uncle Clive and spoke softly and slowly.

‘Two days ago I was in Pinetown blessing a new house for a client. While I was doing my work, I was overpowered by a vision. Visions come to me when people approach me to find their lost ones, but this time it came to me before I was approached. I went back to Eshowe but what I was seeing grew stronger; it gained detail. Yesterday a voice started to partner the vision. It told me to come here and ask about a beating. I am seeing him now as we speak. He is wearing a blue T-shirt and black jeans, black-and-red shoes. He looks like this boy you are with, but darker.’

‘Is he alive there, the place where he is?’ I quizzed.

‘His eyes are open. There are a lot of trees. Take me to where it all happened, and I’ll find him.’

Detective Shange drove us to the scene. When we got there, Manqele stood in the centre of the road and looked around for a while. He stood still in the darkness and right then I recalled that my new sneakers, the ones Simphiwe was wearing without my permission, were black and red.

‘He was here, then he kicked his way out of many hands and ran that way,’ Manqele pronounced, proceeding down the street.

We all followed him. He branched into another street, then another smaller dirt track, and finally reached a cliff at the end of the section. Manqele stood quiet, looking at the rocky twenty-metre fall.

After a while he said, ‘He fell here.’

Some morning light revealed a gentler route down. We followed him down and into a shrubby area. The rising sun uncovered it so clearly, the dense forest before us.

‘He is here.’ Manqele pointed to the forest.

Detective Shange called the Dog Unit. During the wait for sniffer dogs, Manqele suddenly walked into the forest. Shange took off the vest beneath his shirt and left it on a small tree for the Dog Unit to find and track us when they arrived. We stayed on Manqele’s heels, following him for over an hour. We looked around, calling out Simphiwe’s name. Manqele’s step grew less sure when we came to a clearer part inside the forest. He walked slowly, stopped and looked back to the dense trees we’d just negotiated. We turned to look back and saw the Dog Unit emerge. Two officers, white and black. Two hounds, both German shepherds.

The dogs eagerly sniffed Simphiwe’s T-shirt and led the way further into the forest. At a stream they stopped and seemed confused. One barked towards downstream, the other sensed something upstream. The officers untied their leashes. They went off like bullets in opposite directions. Uncle Clive followed downstream with Shange and one Dog Unit officer; I went upstream with Manqele and the other officer.

We did not chase the dog far. Hardly fifty metres upstream we found the beast barking savagely. The dog that sensed something downstream returned, a muddy object clenched in its jaw. Uncle Clive, Shange and the Dog Unit officer followed behind, winded. A tree branch scraped dirt from the muddy object, and I saw the colours red and black. Both dogs now went crazy, barking in the same direction across the stream, but were hesitant to cross.

I saw red and black, and went as berserk as those sniffer dogs. I ran across the stream, went up an incline and found Simphiwe. He was just lying there with his eyes open, his body resting like he was in deep sleep. At first I thought what I saw was a smile on his face, but it was his dislocated jaw. His body swollen, hands like claws. The twenty-metre fall had broken him internally – later it was revealed he had a punctured lung, broken ribs, shattered right collar bone. I imagined him stumbling in pain until his final collapse, here. How long had it taken for him to die? I felt his cold neck, closed his eyes and I sat next to his body until the undertaker arrived.

* * *

The resilience of our bleeding hearts accepted he was gone and searched for the light.

‘He was handsome,’ said Aunt Busi.

‘Lost,’ said Uncle Sbu.

‘But with that brain and vision he could have been a great somebody,’ added Uncle Clive.

‘My baby was gifted,’ Ma said.

His karate coach called him a talent, his running coach declared him a natural runner.

I said, ‘He has joined our father.’

And I remembered him. Not as the addict he was in the end, but the way he was before the wunga.