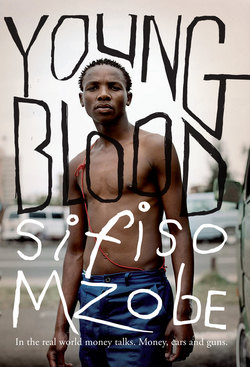

Читать книгу Young blood - Sifiso Mzobe - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. Riding With a Rider

Оглавление1

Riding With a Rider

I remember the year I turned seventeen as the year of stubborn seasons. Summer lasted well into autumn, and autumn annexed half of winter. It was hot in May and cold in November. The older folk in my township swore they had never seen anything like it. Winter nibbled on spring, and spring on summer.

It was exactly thirteen days to the day that I gave up on my high school education. There was absolutely nothing for me in school. My reports were collections of F’s. I was a master mumbler in class. In mathematics I was far below average. Nothing in school made sense, and nothing had since grade one. By grade ten I knew it was not for me. A childish hope of someday understanding had carried me through the lower grades. By May that year, that hope ran out of steam.

When I told my parents of my decision to drop out of school, my mother went into a rage that lasted two days. My father promised me a beating to end all beatings. I showed them my F’s. After her anger had subsided, Ma listened to my explanations, but it was clear she did not understand. Nothing in class made sense, I told her. I was in grade ten, yes, but the last concepts I had really understood were at grade seven level, and I was average at those. In class, my mind was there for the first five minutes – five minutes in which I focused intently. But for the next thirty-five minutes my thoughts would wander, lost into a maze of tangents.

It was May, and the school soccer programme had already been scrapped for the year because of a stabbing incident in the stands during an away game earlier in the year. The beautiful game was something I understood. I was a striker in the school team, and a gifted goal-getter. The soccer pitch was where I shone. It was going to be a long year, with me mumbling wrong answers in class and no soccer to redeem myself. The scrapping of the soccer programme was not so much a reason I left school but rather a footnote.

We all slept on it. Over the next few days, the house was thick with tension. My parents enlisted the help of relatives. Uncles and aunts lectured me over the phone. School is important. Education is the key to a bright future. You are crazy, you should not have done what you did. I was polite, answered “yes” to everything, but my thoughts drifted away. I wished I had super-powers and could shove my school reports into the receiver to let them see the F, G and H grades that meant I did not have the key to a bright future.

My parents tried, they really did. Ma shouted, shook me, asked for more explanations; she tried to understand but could not – the same way I tried to understand in school but didn’t. She even cried.

“I don’t know what I will do, Ma, but I am not going to school. You see my reports; there is not one subject I pass. I can’t do anything right in school. Every day I go there it’s like a part of me dies. Ma, you see my reports every year, there is nothing for me there,” I explained.

“But in this world you don’t just give up. You must keep trying,” she said.

“I know, Ma.”

My parents tried. My uncles and aunts tried. Days rolled on and their calls dried up. The tension in our house slowly lessened.

“At least he was honest with us about his decision. We know where he is. At least he is not like the others who pretend like they are going to school when they are not,” I overheard Ma say to Dad.

* * *

Thirteen days after I left school was my seventeenth birthday.

I was sitting on the wall that doubles as a fence and chilling area to our house, waiting for Musa, when I realised that all the trees on our street had shed their leaves. The wall, roughly painted sky blue on the outside but bare on top and inside, encloses the house in a crooked, incomplete circle. Back then, our four-roomed house wore a coat of plaster as a prelude to painting. This had taken me a day to sand down, which made my body ache in places where I did not know muscles to exist. It was not all in vain, though; at night, with all the streetlights out, the house gave off a dull glow – as beach sand sometimes does. It was close to midnight and I was thirsty.

Our house is meant to be the main feature of the ring on a cul-de-sac. Our blue wall takes up most of the space on the ring, which makes our house the last. The last on the road, the last to get plastered, the last to get a squeezing hug from the walls we call fences. The plastering on our house had been done in prolonged stages, starting with the walls in view – the front and one side. Construction of the wall took even longer. My father often fired builders, but to be fair to him most builders did not even bother to bring a spirit level. The work took years to complete, as something of greater importance always seemed to crop up – water and electricity bills, food, school uniforms and shoes.

A shopping mall had been built on the outskirts of the township, while the builders’ sand grew grass and turned shrubby in our back yard. The paintwork on the wall was mine. It was a weird blue; I told Ma the paint had gone bad.

The process of purchasing the gate to complete the crooked circle of the blue wall was also prolonged. My father had the idea of getting two dogs to guard the gap, but this went nowhere. We would feed the dogs during the day; at night, the gap was silent. Those strays disguised as pets were never there. Every week, Ma returned from the city with brochures and quotations for a gate. Months passed, and the money went on other things.

Our house, which is slightly slanted, sits at the end of 2524 Close in M Section of Umlazi. To this day perhaps, ours is the only road in the hills of Umlazi that is close to being flat. Mama Mkhize’s Tavern stands at the entrance to 2524 Close. The gates to this oasis are forever open, the music always pumping. It is a refuge for all who prefer life lived nocturnally. I knew Musa would be late that evening, so I made my way there.

The moon was plump and yellow, like a sun just risen, and it gave 2524 Close a brilliant bluish shine in the darkness. The midday and afternoon bustle was as distant as yesterday’s newspaper. As the night wore on, 2524 Close took on a crowded silence; the only signs of people passing were simple salutes and the minute amber circles of lighted cigarettes. A neighbour’s daughter kissed a man in the back seat of a car. Around midnight, the smell of marijuana is everywhere in the township. I gulped down a cloud of smoke that crossed my path. The rhythm of my steps made the moon slide and dance a little.

Mama Mkhize sells beer in cans, quarts and by the crate, weed in plastic coin bags and Mandrax pills in singles and even packets. She is a dynamo of a woman, and there are rumours she is related to people for whom killing comes easily.

“My nephew, the one in Joburg, took his BMW to these things, what do you call them . . . agents? Six thousand rands, I tell you, just to have the engine fixed.”

My two Amstels were in her right hand, four loose cigarettes and change in her left. She looked like she was about to give me a hug. Gold snaked around her neck in different layers, shining on her fingers and dancing on both wrists. Her arms were thin but muscular. I always felt things move inside me when I saw her; maybe it was the Diesel jeans she wore, which made her look like a teenager in full bloom. It was unfair that she had inherited the name of her business, for she was only in her late thirties, a fact I vehemently denied until I serviced her car and saw her driver’s licence. I had thought she was younger.

“Sipho, I can see you are still worried about last week. Don’t. You understood what I was telling you, so relax. I told you I understood, and it was just the liquor talking anyway.”

To her list of attributes I must add tact, for what happened “last week” was me crossing a boundary. It had been five days after I’d dropped the “school bomb” on my parents. The smoke from that explosion still lingered in my house, but I had woken up to a good day. I’d fitted brake pads to eighteen taxis at R50 per car. Bulging pockets drove sleep away that night. I felt ten feet tall, and bought a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black from Mama Mkhize.

It was a slow night, when even the twenty-four-hour taverns closed. Mama Mkhize clutched a bundle of keys as I poured my first triple. Courteous, she invited me into the house, and I was surprised by what transpired.

“Johnnie is my favourite too. Mind if I join? I’ll give you a taste of my hand. I have Appletiser, soda water, tonic water and just water. What do you use?”

My choice of dash for the whisky triple did not matter. The taste of her hand – light. Lots of soda water, a film of Appletiser. Easy on the senses.

“I could drink all night if I dashed like you. Light, but it goes down well,” I said.

We drank and laughed. There was a cosy touch to the way we chilled. She made chicken livers as a snack. With each shot, her eyes slanted. She allowed me to get close. I was about to plant a kiss.

“Please leave,” she said in a tone strong enough to knock sense into me. Yet I swear her eyes giggled through the whole thing. The following day, I was at her door with an apology that she accepted with no lecture attached. Since then, I had only stolen glances at her; eye-to-eye contact made me blush.

“Yes, the agents are expensive, but they have professionals and machines that measure the tiniest of details.”

My attempt at bringing a natural, quick end to our conversation failed dismally.

“Nonsense, Sipho. He should have given the car to you. You know when you rev them, the windows of this house tremble.”

Mama Mkhize was a natural exaggerator. Maybe she had to be. She dealt with drunks all day and sometimes all night. I took my beers, smokes and change. My eyes bowed to her direct stare. Her straight face with giggling eyes.

“Maybe next time he’ll come to me. I will charge less than half of what he paid.”

I headed home. I preferred solitude by the blue wall to solitude among drunks.

Musa’s car was parked by the blue wall, doors ajar, when I got home. The colours – white on blue – had my mind retrieving a snapshot of summer skies over my granny’s house at Amanzimtoti. The engine of the BMW 325is was humming. Beer in one hand, Musa was urinating into the concrete channel that drains 2524 Close.

* * *

I knew Musa from the shantytown that occupied my back-yard view. When I was seven years old, the shacks pasted on the hill mushroomed to form a functional neighbourhood. A stream separated our M Section from them. When we were kids, our parents warned us about the shacks and the crooks who roamed there. I nodded my head but did not keep away because there was a shop there that had the sweetest, cheapest sherbets. They loved me at that tuck shop. The granny who owned it always pinched my cheeks and called me her son-in-law.

For every suburb there is a township, so for each section in the township a shantytown – add a ghetto to a ghetto. Fully functional, with such things as committees and such. The shantytown even had a name, Power, after the electricity plant that buzzed day and night at the top of the slope.

It was impossible not to mix with the children of Power because we shared a dusty patch by the stream that we used as a soccer pitch. I was eight years old when I first saw Musa, and I cheered in unison with the crowd for this boy who – though only ten years old – ran circles around the older boys. Musa was the king of football tricks. In twenty-cent games, he always put on a show. In my mind, when I think of our childhood soccer-playing days, I can’t keep out this vision of a stick-man running, the ball glued to his feet, dancing over tackles in a cloud of dust.

We also shared a school with the children from Power. In grade four I shared a desk with Musa, which is when he became my friend. I made the school’s soccer team because of him.

On a football pitch, Musa passed the ball to death. What I lacked in showmanship, I compensated for with speed, blessed with pace and strong lungs. Everywhere on the pitch Musa’s passes found me, through the eye of the needle, across a sea of legs. I would point to the spot and Musa would put it there.

In high school we were in separate classes, so we only hung together after school. When friends change, they get bored of chilling with you. Musa started to hang with the shoplifters – birds of the same feather, I reckoned. On days when he forced himself to pass by my house, our talk was no longer the same. I’d yap about engines and soccer while he rapped about the spoils of shoplifting – things to sell and money to collect.

Musa hung with the shoplifters, who in turn hung with the car thieves, all dressed up swank and bragging about which of the two cliques made cash quicker. Although the signs had been there for a long time, it still came as a surprise when Musa dropped out of school in grade nine. He left for the City of Gold with only the clothes on his back. His return from Joburg – dressed fresh in Versace, in a car considered the holy grail of BMWs in the township – was drenched in a glorious “I have made it” glow.

* * *

“You are a magician, Sipho. My car flies now. When I press it, it goes. I mean really goes. I hope you are ready because we are drinking tonight, birthday boy.”

Musa’s hands were in flight. He wore a brightly coloured, shiny shirt.

His car really only needed a major service. He would have known this had he not just dropped the car and left. But Musa was never interested in that aspect of cars. He was present for almost all of my apprenticeship as a mechanic in our back yard, yet not once did he touch a spanner or change a brake pad. He just sat on a piece of newspaper on our greasy bench and cracked up my father with his shoplifting tales.

“The secrets of these things are in the airflow meters. I played with it a little. Don’t press it too hard or we’ll have to rescue you from a bush somewhere. It is you who is the magician, Musa. Where did you get such a fresh 325is? It is beautiful, my brother,” I said.

Musa rolled in a 325is that glided on seventeen-inch chromed BBS rims. Bar the rims, the car was original in all aspects, with all the electrical switches in proper working order. His 325is had the glassy shine of a Joburg car – as if there was a protective film over the paintwork. Even my father, a die-hard V8 disciple, was a fan of the 325is. A powerful engine on a light, balanced body. Graceful in the brutality of the drift. In the townships, the BMW 325is was – and still is – loved with the same passion by doctors and crooks alike. The sound in idle was a daring rumble.

“Put those in the back seat. There is a party waiting for us in Lamontville.”

I threw my Amstels into the cooler box. A few sparks and then a flame revealed a devilish smile as Musa lit a cigarette.

“You drive, Sipho, I drank too much during the day. Start at Z Section – two girls we have to pick up there,” he said.

We slid through to the brighter streets of Z Section, to the bigger new houses near my old primary school. As kids on the way home from school we were in wonder at the machines that sculpted the hill, accelerating the disappearance of the guava, mango, peach and mulberry trees that were once so abundant in Umlazi. The new houses on the hill had yards the same size as our four rooms, as well as more bedrooms and an added lounge. These were the calmer parts of the township; the streets were quiet, and no adolescent cliques tried to break the night.

The 325is was flirtatious under my palms; the more I pushed it, the further it sat. Musa, my waiter, supplied cooler-box-cold beer. Under a yellow streetlight, two shapes waved in silhouette. All I could make out were curves.

“Stop by the third light; it is them.”

Musa hugged both girls and arranged the seating so that he was with the taller girl in the back seat.

“Please play me number six on this CD.”

My companion in the front spoke with the ease of nightlife. A request from thick, heavily glossed lips revealed a full, warm smile. The flowery sweetness of perfume rushed up my nostrils when she moved closer to the stereo in search of the skip button.

“Below the volume knob,” I said.

At stop streets, I stole looks at her. She turned up the volume and sang to the song. Gradually, I made out the contours of her face. Top-heavy oval, I confirmed under the fluorescent lights of a petrol station.

Township night-riding is strange, for there is an unspoken agreement which, although not binding, stipulates that we are instantly familiar. No need for formal introductions. I caught their names when they answered or made calls. We bought snacks at the petrol station shop. In the pay queue, Sindi, my companion in the front seat and the more curvaceous of the two girls, smiled and looked up at me. She offered one earphone of her cellphone radio.

“Listen. It’s the same song we played in the car,” she said.

In the reflection on the pay booth glass, I tried to check her out but found her already there. She forced a blush and smiled. We entered Lamontville through the back door.

A few streets from the venue I heard house music and followed it, my ears leading me to the exact spot. Our expectations were met by a convoy of cars. Musa jumped out of the 325is well before I turned off the ignition. The host was a friend of Musa’s who went up and down the street and broke the night by spending a few minutes in each car. Whisky glass in hand, in each car he uttered the same words: “It’s not even a party. I don’t know who started this rumour. Could Durban be so boring that people have time for chit-chat? We are all family, though. I mean, I was bored anyway and now I have booze to drink and chicks to look at. You are chilling on my street. I am giving you the freedom of the tarmac. Drift, spin, do whatever. Bang your system to the maximum if you like.”

He passed out in Musa’s car, quickly and suddenly, before the drifting started.

“It had to happen, Sipho. He drank from every whisky bottle and smoked all the blunts busted near him,” said Musa.

Loud whistles and laughter greeted Musa and me when we carried the host inside the house – a homely, tidily renovated four rooms with fully fitted kitchen, the tiles in the bathroom colour-coded to the handwash basin and bathtub. He was a sucker for blue – the BMW under the carport, the bathroom, the curtains and the comforter in his bedroom. He was dead weight, a thud on the bed. Musa took off his shoes and rolled him to the centre of the double bed. The blackout and the emptiness of the house were signs of his bachelor status. He was barely there when his eyes opened.

“Thanks, Musa. I’ll call you tomorrow about that thing. Lock from the outside and throw the key here.”

He pointed to the bedroom window. A loud snore sounded when we tossed the key inside.

The exercise provided much-needed fresh air, which was suddenly diluted by weed smoke as we moved towards our car at the end of the convoy. I knew some of the high-rollers, most of whom were from my township. Musa knew everybody, though. He stopped at almost every car, and was saluted by their crews. I kept cool as the introductions nonchalantly rolled off. But I quickly headed for the car, bored with standing next to Musa while his friends eyed me up and down. And I needed to chase away the slight wave of sobriety that was creeping over me.

Our two companions were dancing by the 325is. The smell of petrol, coupled with the sound of high-revving engines, was heavy in the cool wind. It always starts with one car revving until the engine clocks. The shrieking of whistles meant it was time to use the freedom of the tarmac. In the township, they say the streets talk; a few handbrake turns will turn the streets to pages, with tyres as black-inked pens.

The whistling climaxed as the first car started.

The roads in Lamontville are basically a touch wider than one lane divided into two. There was no space to drift really because of all the cars parked on one side of the road. The few pockets of space were at the apex of the convoy and at the base, one car behind us.

A red matchbox BMW 320i was the first to show off. It turned gently yet descended with fury, first gear pushed to the maximum and double taps on the accelerator when it shifted to second gear. Full throttle again to pass us as a red blur driven by smiling gold teeth. He pulled the handbrake, the wheels locked, and the 320i turned slightly over a half circle. It hardly stood still as whistles and screams filled the air. It ascended full blast but did not turn at the top.

“He is scared. It could have been better,” I said, not meaning to voice my thoughts.

Sindi was next to me, our reflection in the windows of the 325is proclaiming us a seasoned couple.

“Maybe you don’t even know how to do this, but you criticise,” she said.

“It is nothing, I am telling you. I can turn it two, three, maybe four times where he did it once.”

“Such a liar. You know, I have never been inside a spinning car.”

“If you are not scared, you can ride with me. I will be the last to spin. We’ll open the sunroof. You can wave to everybody.”

A few more tried, but none were perfect turns. Our reflection was joined by another couple – Musa and his girl.

“Before you start, please take the cooler out, otherwise everything will spill all over my seats,” Musa said.

“It’s alright, Musa, there won’t be a single drop.”

“There is no way I am risking that.”

“Key?”

“Are you really that drunk? The key is with you, Sipho.”

Sindi’s eyes were hesitant. I started the engine and gauged the handbrake and clutch, then tested it at full throttle while still. The 325is responded with a twitchy bounce. Through the sunroof I put out my hand and beckoned Sindi over.

“Come with a dumpy,” I shouted over the engine.

She opened the door and sat down in one motion. I released the handbrake and stepped full power on the accelerator. The 325is stalled, and took a few digs on the tarmac. When I released the clutch it was like we were inside a bullet. Sindi was pushed deep into her seat and let out a joyful scream. I went full on the gears, double-tapped the accelerator from first to second. Simply to show off, I tapped it three times from second gear to third. At the top of the convoy I changed it down to second, handbrake up. The 325is turned and stayed. Full throttle in neutral once again, all windows down. I heard whistles over the engine sound. I pushed it to metal to drown them out. When it clocked, I put it into first and second with double taps all the way down to the end of the convoy. The smell of burnt tyres and weed smoke gushed in through the windows.

“When am I showing through the sunroof?” shouted Sindi.

“I’ll tell you when we get down there,” I said. Third, fourth, back to second and handbrake. The car turned a perfect one-eighty degrees.

“Now!” I said.

Sindi balanced her legs on both seats. She had ample space on both because, as I started to spin, the force of it all meant I was pressed against the leather of the door and used only half of my seat. I turned the 325is three full circles while she swayed through the sunroof. I peeked up: her face had the expression of a scream but I heard nothing over the engine. At the end of the last circle, I saw that the crowd had gathered around the 325is. I went full throttle in neutral. Every time the engine clocked Sindi banged her hands on the sides of the sunroof.

“Sindi, get down, I’m parking,” I said.

“One more, please,” she pleaded, with childish glee.

“Maybe later.”

I parked on our spot. Cheers and whistles as we opened the doors. Sindi was out of breath.

“How was it, Sindi?”

Musa gave me high fives. Sindi had no words – just both thumbs up and an accusing smile directed my way.

The next car went full blast, only to hit the pavement on a turn. Both wheels on the impact side gave way, crumpling completely; the car nearly tipped over.

I was low key for the remainder of the night. While Musa paraded his girl around, I was glued to the back seat with Sindi. She took off her jacket. My hand was frozen from the futile search for beer in the cooler box – only ciders remained.

“You guys can drink. Twenty-four beers just for the two of you?”

“You know it is cooler outside.”

“I am comfortable here. Without the jacket I will cool down. You are scaring me – why are you looking at my mouth so much?”

“Your lips, Sindi.”

“Do I have something on them?”

“No.”

“What then?”

“They are beautiful. Like I can eat them or something.”

She smiled and performed her shy-girl routine when I came closer.

“Wait! Let me wipe off this gloss first.”

She retrieved a tissue from her handbag. A sequence of nibbling, tongue, nibbling and pause ensued.

“I am not going home. My mother is already on to us. She called the friend we said we were visiting. We might as well face her in the morning. I know Ma – she will be cooler then,” Sindi said.

Smooches graduated to something more ferocious. The leather squeaked as she straddled me. Ebony women and their bottom-heavy shape seem to complement jeans. We nibbled on, breathing into each other beer, cider, cigarettes and the remnants of lip gloss – a faint strawberry flavour. Sindi removed my hands when I explored between her legs.

“Don’t rush; we cannot do everything in the open like this,” she said.

I cooled down, content with kisses because I was sure to score. Even if I had been blind, the signals did not come clearer than that.

Deep in the groove of kissing technique exchange, we were disturbed by a knock on the back windscreen. It was a guy with gold teeth, the first one to spin in the red BMW.

“Sorry, bro, I thought you were Musa. Where is he, by the way?”

“Somewhere by the silver 7 Series up there,” I said.

Sindi moved aside, rolled her eyes and tugged playfully at my T-shirt when I stepped out to attend to Gold Teeth.

Gold, gold and more gold. Hoops for both earrings, for each alternate tooth, a large chain around the neck and thick bracelets for both wrists. He was about my age and dressed in a Versace shirt. Trousers, belt with oversized buckle and shoes were all Hugo Boss. In his hand he clasped a clump of crushed weed.

“Do you have rolling paper?” he said.

“No, but maybe Musa does. He is coming this way; you can ask him.”

Musa was jovial, hand in hand with his chick. When I looked at her, I saw the unnerving resemblance to Sindi as they sat next to each other in the back seat of the 325is.

“Vusi, where is my M3?” shouted Musa.

A smile from Gold Teeth.

“You will get it, Musa. Do you have rolling paper?”

“I blame this weed. Rolling paper, rolling paper? It has been three months since I placed my order, Vusi. Just say if you can’t get it and I’ll place my order elsewhere.”

“You won’t believe this, Musa, but I have had three already. One even had a Rob Green conversion. But the thing with all of them is, they go dead within five minutes. And you know with these helicopters they have now, I have to split.”

“Well, this money will not wait long for you. Get me what I want.”

“For sure,” Vusi said.

“Rolling paper is under the ashtray. Any beer left, Sipho?”

“We are out,” I said.

“It’s late, time for Johnnie anyway.”

Vusi rolled a fat, cone-shaped blunt. When it was my turn to hit it, I turned to smiles and expectant eyes from the back seat.

“Do you want some?” I asked the girls.

Synchronised nodding of heads. I passed it on to both girls. Musa opened the Johnnie Walker Black. I remember taking the first sip, and Sindi snuggling next to me in the back seat. Then, from the top of the convoy, a black cloud in attack formation headed straight for us, smothering me.

* * *

The first thing I saw when I opened my eyes was the blue wall. Then Musa on his phone. He puffed a cigarette and pissed into the concrete channel.

“I blame Vusi and his weed,” Musa shouted over the phone.

“Where is Sindi and your chick?”

“She is not my chick. Just some girls I met in town yesterday and bought them lunch. They both blacked out like you. I dropped them at N Section – cousin’s house or something.”

“That was strong weed, Musa.”

I was struck by the faint blue of dawn when I stepped out of the car. The clock read 4:17.

“Is this the right time?” I said.

“Yes.”

“You kept your promise, Musa. You got me drunk on my birthday. Catch you later in the day.”

“Sipho, wait. Here is the cash for fixing the car, although the way you were spinning it you may have to fix it again soon. All the crooks were asking about you.”

“These cars were made for spinning, Musa.”

“What will you do with the money, anyway?”

“I want to buy a phone.”

“I got a spare phone. You can take it; then I’ll only pay like a hundred rands or something.”

“Musa, you are Mr Money but always bargaining.”

“This is a good deal I am giving you. Take a look behind the gear lever.”

“I’ll take it, thanks, Musa. Call you when I get a SIM card. Anti-hijack system.”

“Go sleep, Sipho. You are mumbling now.”

“No, Musa. Anti-hijacks. What makes M3s go dead within five minutes are the anti-hijack systems. Someone came to see my father with a similar problem. The anti-hijack in his car was going haywire, so we disconnected it.”

Musa came close with a seriousness I did not know him to possess.

“Can you override them? Can you disconnect them?” he said.

“Yes, I can do both,” I said.

I pissed on the blue wall. In the mirror in my room, I saw myself drunk. On the small table by my bed I picked up the birthday card left by my girlfriend, Nana, sixteen hours earlier.

It read, “Happy Seventeen, Sipho, I luv you.”