Читать книгу Soldiering through Empire - Simeon Man - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE

Securing Asia for Asians

MAKING THE U.S. TRANSNATIONAL SECURITY STATE

IT WAS FALL OF 1952, and Hsuan Wei was twenty-four years old when he entered the United States for the first time, determined to change his life one way or another. Wei was a first lieutenant of the Chinese Nationalist Marine Corps and had been given the opportunity to go to the United States to further his military training. The benefits of pursuing it far outweighed the uncertainty he may have felt about leaving home. In September, with few belongings, he arrived at the U.S. Marine Corps School in Quantico, Virginia. On the other side of the Pacific, the Korean War raged unabated, and tensions between the Republic of China and the Communist mainland increased to the threat of impending war. While global events were driving factors behind Wei’s sojourn, they figured mostly in the back of his mind. As far as he was concerned, he was simply seizing an opportunity to advance his military education and career.1

Wei’s transpacific journey hinted at an ordinary life soldiering through empire in the age of decolonization, a far more common story than historians have acknowledged. Wei, in fact, was one of an estimated 141,250 foreign nationals who made their way to the United States for military training in the 1950s. These visitors hailed from all over, from Taiwan, South Korea, South Vietnam, the Philippines, Iran, Indonesia, and many other countries, each undergoing the turbulent processes of nation building after colonial rule. Though they came from different parts of the world, these subjects shared striking similarities. Socioeconomically, they were not disenfranchised people desperate for work but were aspiring individuals who sought to elevate their positions in their national armed forces and, for some, in their governments. Many had served in colonial and imperial armies before their countries’ liberation from colonial rule, and chose to continue a career they knew garnered respect. One Korean soldier, Yi Chiŏp, recalled his time serving in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II: “I worked within the system to gain as much education and training as possible.” This decision tainted him as a “collaborator” among other Koreans, but it allowed him to climb the ranks of the new Korean Constabulary after the war.2

The U.S. militarization that accelerated after World War II was the root of their transpacific journeys and military training. After the war, the United States confronted local insurgencies throughout the former Japanese empire, waged by ordinary people who refused the terms of the American liberation. Cross sections of the population including industrial workers, military base workers, peasants, labor organizers, and students in Korea, Japan, Okinawa, the Philippines, and elsewhere redoubled their efforts for national self-determination. They rekindled longstanding anti-Japanese sentiments and directed them at the United States. U.S. officials felt alarmed, convinced of a global communist movement afoot in Asia. The U.S. state responded by laying the groundwork to fortify indigenous forces, to assist “free nations” to defend themselves from “communists.” In 1949, these efforts cohered in the Mutual Defense Assistance Program (MDAP), the first major U.S. military aid initiative that would funnel billions of U.S. dollars to train and equip the national armed forces of allied states over the next decade and beyond.

The making of this transnational security-state apparatus in Asia created massive disruptions on the ground and led to the proliferation of Asian soldiers across the Pacific. To be sure, Asian colonial conscripts had circulated in this region for some time, most recently during World War II when Koreans had been mobilized to far-flung places of the Japanese empire to serve in the imperial army and to labor in factories and mines.3 In one sense, this chapter traces the lives of these martial subjects as they transitioned from the Japanese colonial empire to the U.S. liberal empire. In the context of the protracted global struggle against communism, particular Asians who were newly liberated from colonial rule became the functionaries of the United States’s burgeoning transnational security state in Asia.

This chapter explains how overriding U.S. concerns about global decolonization led to the growing presence of Asian soldiers in the Pacific, and how they in turn provided the endless justifications for the U.S. empire. American military advisers spoke often of these Asian soldiers as “assets,” prized as manpower and for their knowledge of the local terrain. During the heaviest fighting of the Korean War, their use as “buffer” troops purportedly saved “hundreds of thousands” of American lives.4 U.S. state officials reasoned that they were not merely colonial mercenaries mobilized to do the gritty work of the U.S. military but were “free Asians,” democratized subjects who could demonstrate the promise of U.S. liberal democracy to the rest of decolonizing Asia. Conscripted to build Japan’s East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere just a short time before, these subjects emerged as the vanguard of a new pan-Asianism—an “Asia for Asians”—that the United States pursued deliberately against charges of global white supremacy and imperialism. The militarization of Asia against communism and the liberation of Asians from colonialism, the twinned vexing projects of the United States in Asia after World War II, became embodied by these Asian soldiers.

While U.S. officials touted these soldiers as free Asians, they were also citizen-subjects with individual and collective aspirations and grievances that posed challenges for the U.S. state. At a time when these officials grew increasingly concerned about communism at home and abroad, they invariably cast these subjects as “subversives.” The inclusion of free Asians into the U.S. transnational security state, this chapter contends, facilitated movements, encounters, and fleeting alliances among Asian peoples across the U.S. empire that magnified the very problem of subversion it aimed to contain. Not least, it brought people like Hsuan Wei into the United States over the course of the 1950s. The chapter ends by exploring how the projects to militarize and liberate Asia devolved into a national security problem at home, involving “immigrants,” deserters, and asylum seekers. In the end, policing against subversive Asians, in the United States and across the Pacific, proved pivotal to preserving the security of the U.S. empire and the promise of “Asia for Asians” in the post–World War II era. The problem of subversion that came to confound U.S. state officials was a byproduct of the making of the transnational security state, an unintended consequence that became indispensable to its functions.

THE “RED” MENACE AFTER LIBERATION

This story begins in Korea, a country far from the minds of most Americans when the Japanese empire fell, but one that would matter greatly in due time. In September 1945, when Lt. Gen. John Reed Hodge and his XXIV Corps occupied the southern half of the Korean Peninsula, the United States had yet to articulate a coherent plan for what to do with the former Japanese colony. To Koreans, August 15 marked the abrupt and long-awaited end to colonial rule. But it seemed there were dark signs, for their liberators had bigger schemes. Save for a short and violent U.S. naval expedition to open up the “Hermit Kingdom” in 1871, a little-known war that precipitated the signing of a treaty of “peace, amity, commerce, and navigation” in 1882 and American expansion in the Pacific in the late nineteenth century, the United States had never taken direct interest in the peninsula.5 In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt had recognized Japan’s “special interest” in Korea after Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, and after World War II Korea’s fate would appear to default to American interests in Japan yet again. In Japan, the goals of Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s military occupation were clearer from the start: to effect a “complete” and “permanent” program of demilitarization and democratization, and to reform the enemy into “enlightened” subjects of democracy. Meanwhile, Hodge’s task in Korea was to disarm the Japanese and send them back to Japan.6

Hodge’s broader mission became clear soon enough, when his team encountered revolutionaries on the ground. Two days before Hodge’s arrival, Yŏ Un-hyŏng, a moderate leftist with a long history of anti-Japanese activism, declared the founding of the Korean People’s Republic, a de facto government driven above all to establish a unified independent Korean state. The People’s Republic captured the aspirations of Koreans throughout the countryside, particularly of peasants who had borne the brunt of Japanese colonial policies. In the weeks and months after liberation, the work of building a new nation was animated through “people’s committees” that proliferated in the rural south. These were locally administered, grassroots organizations that infused anticolonial patriotism with concrete goals such as land redistribution and the purging of colonial collaborators from the police and other government posts. Their radicalism alarmed U.S. authorities. After the People’s Republic boldly called forth a national election to unify the country, Maj. Gen. Archibald Arnold, the military governor of Seoul, warned, “There is only one Government in Korea south of the 38 degrees. For any man or group to call an election as proposed is the most serious interference with the Military Government” and constitutes “an act of open opposition” to the United States that would not be taken lightly.7

This “open opposition” continued as the majority of Koreans realized that the United States had come not to liberate them—that is, to help them reconstruct society from the ground up—but to ensure the continuation of the established colonial order. Within a week of Hodge’s arrival, the State Department had identified “several hundred conservatives” who officials believed could be entrusted to lead South Korea.8 They were landowning elites who had profited on the backs of peasants during the colonial period, and exactly the kinds of “collaborators” and “feudalistic” legacies that the people’s committees sought to purge. In addition, the Military Government revived the colonial National Police, a much-hated symbol of Japanese oppression, as its instrument for suppressing radical activities. Koreans who remained in Allied Occupied Japan also saw a return to business-as-usual. In a petition to General MacArthur in May 1946, three Koreans alleged that Japanese police violence against Koreans had escalated since the occupation. “We, Koreans, have welcomed [the] Allied Forces as the army of emancipation with maximum respect and affection,” they prefaced their grievance, “[h]owever, to our great regret, the Japanese police has begun again to intervene, suppress and behave violently…. And we cannot understand that they do so by agreement with Allied Forces, as they propagate.”9

According to Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP) officials, the retention and expansion of the Japanese police force in the first year of the Allied Occupation of Japan was a matter of “necessity” due to the “adverse rate” of replacements and “acute shortage” of American troops.10 Still, authorities could not ignore these allegations. They responded by digging into the political pasts of the petitioners. Upon investigation, agents of the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps in Tokyo found that Chun Hai Kim, the “principle instigator” of the petition, was a member of the Japanese Communist Party and had a lengthy police record, including a homicide conviction. As for the claim of police abuse against Koreans, their closer look into some of these cases revealed “not cases of actual persecution” but of “Korean resistance to Japanese Police attempting to maintain order.” Having fully discredited the petition, the agents took it one step further: “It is evident that the Allied Council and the Occupation Authorities are going to be bombarded with a series of such petitions, designed to create the impression that these statements are representative of popular opinion or expressions of bona fide groups of citizens.” What they actually represented, however, was the “classical approach” of communists to “mislea[d] [and] exaggerat[e]” the facts, “and plainly designed to strengthen the Communist Party,” in Japan and elsewhere “in the Orient.”11

Officials’ interpretation of local anticolonial grievances as strategies of a global communist crusade reflected more than paranoia; it indicated how the United States would come to criminalize recalcitrant colonial subjects. In the Philippines, for example, the Hukbalahaps, an anti-Japanese guerrilla force during the war, became an “internal security” threat promptly after liberation because it continued to rally peasants against corrupt landlords and colonial elites who maintained power.12 In Okinawa, longstanding indigenous struggles against Japanese land policies were cast as the work of saboteurs to undermine the U.S. occupation and its plans to build military bases. “The pattern of the disturbance planned for the U.S. bases throughout Okinawa island,” according to the 441st Counter Intelligence Corps Detachment in 1947, “will most probably take the form of a revolt by violence, following the line of strategy and tactics adopted in struggles in colonies throughout the world.”13 Throughout the post–World War II Pacific, anticolonial movements thus intensified in Central Luzon, Okinawa, Taegu, Cheju, and other locales, fueled by the re-entrenchment of colonial class relations and the violent suppression of worker and peasant revolts in the name of anticommunism.

The crisis of legitimacy that confronted U.S. officials in Asia would deepen as they revived the structures of the colonial state to make the region stable for capitalism. In Korea, Hodge understood the crisis and observed to the Secretary of State that, in the eyes of Koreans, “[t]he word pro-American is being added to pro-Jap, national traitor, and collaborator.”14 His solution for dealing with this “anti-Americanism,” however, proved misguided entirely. “One of the principle factors adverse to Korean-American relationship in South Korea,” he noted to the commanding generals of the U.S. Army Forces in Korea, “is a plain, unvarnished lack of courtesy” for Koreans by American soldiers. “I see evidences of this everyday,” of Americans “mak[ing] fun of the Koreans, calling them ‘gooks.’” Lest Americans be construed by Koreans as another colonizer with wanton disregard for their lives, the command should “effect spot checks on conduct and prompt handling of offenders.”15

If Hodge thought that curbing the racial prejudices and “discourtesies” of American soldiers could placate Koreans and win their allegiance, he gravely misjudged the depth of their anticolonial aspirations, and failed to see how race played a far more important role in legitimating the U.S. occupation. From the start, Americans routinely characterized Koreans as a simple-minded people, with “few ideas” beyond a deep hatred for the Japanese and desire for immediate independence.16 According to the State Department’s political adviser, William Langdon, this was a main explanation for the Autumn Uprisings, a massive revolt in the fall of 1946 that shook the American occupied zone. He argued that the revolt exposed once and for all the Koreans’ “latent savagery and incapacity for self-government.” Langdon blamed the uprisings on the Koreans as well as the Japanese, whose authoritarianism taught Koreans “to only respect force,” hence the reason why they “now submit meekly to a dictatorial alien controlled regime in North Korea.”17 What was once the Japanese empire’s “Korean problem” (that of “uncivilized” colonial subjects within the body politic) had turned quickly into a communist problem for the U.S. Military Government. The task at hand, U.S. officials understood, entailed “teach[ing] the responsibilities [and] advantages of democracy” to Koreans and steering them clear away from communism.18

These dual projects—of civilizing Koreans and suppressing their radicalism—cohered in an experiment that Americans had tested long ago in a different colonial setting in the Philippines: to instill martial discipline in the population and to build up an indigenous security force. This process began with the arrival of Lt. Col. Russell D. Barros in September 1945 as part of the XXIV Corps. Barros was an officer in the Philippine Army who had mobilized a band of Filipino guerrillas as part of the liberation of Luzon in 1944, and who was prized for his experience working with Asian soldiers.19 His travel from one U.S. colonial outpost to another, and the knowledge he acquired and implemented along the way, exemplified the kinds of transnational circuits that would shape the U.S. military empire in Asia over the next two decades. With Barros’s guidance and with SCAP approval, Hodge directed the formation of a Korean Constabulary in January 1946, which served as an auxiliary to the National Police, with infantry units established at each province.20 Similar to the one formed at the start of the U.S. colonial rule of the Philippines, the Korean Constabulary was tasked with maintaining “internal security” of the liberated colony in order “to get a start for the future” when a viable government was established.21

In the early months of 1946, young Korean men flocked to the recruiting stations, heeding the calls of newspaper ads and street recruiters, and eager for the chance to resume earning a steady wage. Many had been officers of the Imperial Japanese Army before liberation ended their careers abruptly. They tended to hail from middle-class backgrounds and had seen joining the Imperial Army as an opportunity to further their education and training, driven by the prospect of job security and an elevation of their class status. When the war ended, some envisioned an even greater purpose: they wanted to be the leaders of the new nation’s army. To American officials, these men were exactly whom the Constabulary needed. They were ambitious and educated Koreans with the right blend of patriotic zeal, some English-language facility, and above all military experience. As recruitment progressed in the spring of 1946, U.S. advisers began making necessary changes: they replaced Japanese weapons and uniforms with American ones, translated U.S. military training manuals into Korean, and even added Korean history to the curriculum.22 In short, the Constabulary was to become an American experiment in building a Korea for Koreans.

Faced with a population that seemed to grow increasingly resentful of the Military Government and its policies daily, Hodge pushed for an accelerated expansion of the Constabulary at the end of 1946, in preparation for potential future insurrections. To draw recruits, Military Government officials kept the entrance requirements to a minimum: a candidate had to be at least twenty-one years old, without a criminal record, and to hold the equivalent of an American eleventh-grade education to be admitted as an officer.23 The lax requirements helped drive the numbers, but other forces were at work. As the National Police continued to crack down on political dissidents, those who bore the brunt of the repression came to see the Constabulary as an armed haven. “Many of the men the Americans recruited for our constabulary service,” John Muccio, President Harry Truman’s representative to Korea acknowledged later, “were self-styled refugees newly arrived from the north of the 38th parallel, who were accepted without proper investigation.”24 Within a year’s time, between the spring of 1946 and 1947, the Constabulary had grown from a force of three thousand to ten thousand men.25 Their loyalties could not be determined with certainty.

In October 1948, two months after Syngman Rhee declared the founding of the Republic of Korea (ROK), a massive rebellion rocked the southern peninsula and reverberated around the world. On October 19, upon receiving orders to deploy to Cheju Island to suppress a growing insurgency there, elements of the 14th Regiment of the Korean Constabulary pursued other plans: they mutinied. Forty soldiers stationed at Camp Anderson murdered their officers. They seized control of the city of Yŏsu within hours. The next morning, the number of rebels had swelled to two thousand, drawing disaffected soldiers and local people into the ranks. Officers told their men, “The thirty-eighth parallel has been done away with. Go get your guns and assemble.”26

With this gathering force, the rebels quickly spread to the nearby city of Sunch’ŏn. They marched through the streets and waved red flags and sang communist slogans, announcing their victory. They established “people’s courts” that tried and executed members of the police and their families as well as other government officials and landowners. The American adviser to the Korean Constabulary James Hausman recalled of what came to be called the Yŏsu-Sunch’ŏn rebellion, “All hell had broken loose and we had nothing to stop the onslaught.”27 Meanwhile, on that same day, the South Korean Labor Party called for a general strike in Taegu, rallying students and workers to demand the dissolution of Syngman Rhee’s government and the withdrawal of American troops from Korea.28

The Yŏsu-Sunch’ŏn rebellion drew the attention of international observers and journalists; many who flocked to the area documented the bloodshed on the ground. “The city stank of death and was ill with the marks of horror,” Life photographer Carl Mydans wrote in his notes to his editors.29 In the eyes of the “free world,” the mutinous soldiers and the violence they unleashed belied a precarious South Korean state that seemed to have lost its handle on the “Red menace” completely. Military officials appeared to have seen the signs coming. Earlier that summer, counterintelligence agents intercepted instructions from North Korea urging communists to “infiltrate into the South Korean Constabulary and begin political attacks aimed at causing dissension and disorder”; by late summer, agents had identified the 14th Regiment as the most dangerous and suspected it was close to mutiny.30 A deeper look would have revealed that unheeded warnings stemmed back even earlier to the hasty recruitment drive of 1946–47. But there was no time to reflect on missed opportunities. Rhee struck back hard against the rebels. Led by American advisers and carried out by Korean colonels seasoned in Japanese antiguerrilla campaigns in Manchuria, the counteroffensive was swift and brutal. One week after the mutiny began, an estimated 821 rebels were killed and nearly 3,000 captured; 1,000 or more escaped and slipped into hiding. Peace was restored momentarily.31

The following weeks proved critical for Rhee in his drive to consolidate power in the budding South Korea. The conservative leader had been biding his time since his return from exile in 1945, and now he did exactly what he needed to demonstrate his legitimacy to his American backers. Soon after the pacification of Yŏsu and Sunch’ŏn, Rhee ordered the Constabulary to intensify investigation of all its units and to purge those with “communistic tendencies.” All who had taken part in the rebellion were brought before courts-martial and charged with mutiny and sedition.32 With the passage of the National Security Law in December 1948, the hunt for subversives grew more emboldened and led to the roundup and screening of more than two thousand officers and the imprisonment of more than four hundred on charges of conspiracy, murder, and mutiny, among other crimes.33 Such draconian measures reflected Rhee’s shortsighted understanding of what had happened: the Yŏsu-Sunch’ŏn rebellion was only a problem of “Communist infiltration.” As such, it required bureaucratic solutions, starting with the prompt purging of subversives. During the process, American military advisers resumed the buildup of the Korean Constabulary and implemented better screening of new recruits.

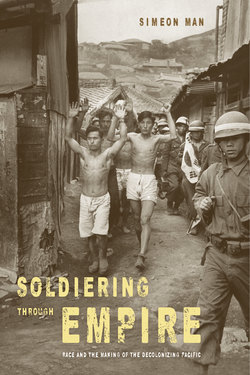

FIGURE 2. Captured rebels of the Yŏsu-Sunch’ŏn rebellion, October 1948. (Photograph by Carl Mydans; The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images.)

Rhee’s crackdown facilitated the transition from the American occupation to the new Republic, ensuring no place existed for political dissent in his anticommunist state. The crackdown worked more broadly to secure South Korea’s place in the newly reconfigured Pacific region, the contours of which were becoming clearer by this time. In October 1948, the National Security Council outlined the first U.S. policy strategy toward building a new Pacific regionalism, centered on Japan and its economic recovery. The “reverse course” of U.S. occupation objectives in Japan meant several things, most notably the return of previously “purged” conservative leaders to power and the promotion of unfettered capitalism. Both of these objectives had been pursued against the increasing militancy of organized labor and communist movements. But the reverse course also signaled a broader transnational calculus to revive Japan’s industrial capacity and export markets in Asia, keeping the periphery firmly connected to the capitalist world.34 The security of anticommunism in South Korea and the resumption of Japan’s industrial economy emerged as integral projects to transform the Pacific region into a beacon of free trade and a part of the “free world.”

Since the end of World War II, in the span of a few years, American policy had gone full circle, from dismantling the Japanese empire to resuscitating it. Common people throughout Asia revolted against what they saw as the revival of Japanese dominance in the region through the aid of “American imperialists.”35 But to U.S. officials, this was to be a more liberal and democratic pan-Asianism than the East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, one tempered by the U.S. commitment to support the independence of postcolonial nation-states. It was to be far removed from Japan’s erstwhile militarist endeavors. Yet this was no mere ruse for empire. In fact, the promise of “Asia for Asians” demanded a differentiation between “good” and “bad” Asians, between those to be incorporated into the postcolonial state and those to be expelled from it, and American officials put their faith in the military to accomplish both. The Korean Constabulary, driven by the dual mandates of disciplining martial subjects and making war on those who refused the American liberation, functioned as the quintessential vehicle for postcolonial state building.

The Yŏsu-Sunch’ŏn Rebellion was not an aberration of an otherwise promising start toward the fulfillment of a national project. Instead, it was the result of the accumulated grievances of ordinary Koreans since the start of the U.S. occupation. It was their collective refusal of American designs for their postcolonial world. The failure of American officials to face this fact would haunt them not only in Korea but also in other contexts, wherever the U.S. military intervened.

MILITARY EXPANSION AND SUBVERSION

In November 1948, with the Yŏsu mutiny recently subdued, Secretary of the Army Kenneth Royall issued a directive to all U.S. Army commands that outlined the protocol for handling “subversive and disaffected personnel.” The events in Korea made him nervous about the loyalty of his own American troops. The terms “subversive” and “disaffected” personnel described subjects who had engaged in any number of political activities or had “shown lack of loyalty to the Government and Constitution of the United States” by acts, writings, or speech.36 Royall’s directive breathed new life into these definitions by empowering commanders to “detect” and “investigate” such personnel. The directive tasked them with classifying and maintaining a detailed record of each individual, including name, rank, army serial number, and a statement indicating the basis for the subject’s classification.37 The suppression of the Yŏsu rebellion appeared to have contained one specter of communist subversion only to give rise to another within the U.S. military, one that gained increasing focus and clarity in the late 1940s yet would remain more elusive than ever.

In many ways, the problem of subversion in the U.S. armed forces was a product of popular front activism for racial equality in the early 1940s. In a memorandum dated February 1946 and titled “Communist Infiltration of and Agitation in the Armed Forces,” the War Department’s Director of Intelligence Lt. Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg made this connection clear. Admittedly, the problem had roots stemming back to 1920, he noted, when the Communist International first ordered communist parties around the world to “carry on a systematic agitation in its own Army against every kind of oppression of colonial population.” By the start of World War II, this global movement had transformed into active pursuits against the Jim Crow military in the United States. As Communist Party members entered the services in an attempt to organize from within, they targeted “negro [sic] soldiers and enlisted personnel” in particular. The Communist Party, under the guise of “front” organizations such as the American Youth Congress and other civil rights groups, had unleashed a “whispering campaign” to indoctrinate soldiers and sailors, stirring up black servicemen especially.38

But it was after the war, as the United States continued to keep American troops overseas, that such activities posed an actual global threat to U.S. security. “At first,” Vandenberg continued in his memo, “the apparent purpose of the Communists seemed to be propagandizing against this country’s occupation of certain areas in the Pacific and the Far East.” But by the end of 1945, “Communists” were actively agitating GIs wherever they were stationed abroad, fueling the growing sentiments of the American public that overseas servicemen ought to be returned home without delay.39 Handwritten letters—hundreds and thousands of them—flooded the offices of elected officials in November and December, written by GIs in Hawai‘i, Okinawa, Yokohama, Manila, Frankfurt, Nuremberg, Paris, and other places. In Manila, “Home by Christmas!” became a seditious slogan that seemed to appear everywhere; as Nelson Peery, a radicalized black GI at the time, recalled, the words were scratched onto road signs and painted on the latrines, on the doors of officers’ quarters, in recreation rooms, and in mess halls.40 Authorities watched these signs nervously, convinced of sedition stirring in the military.

Then on Christmas Day 1945, as though confirming these worst fears, four thousand American soldiers in Manila staged a demonstration. The soldiers marched to the 21st Replacement Depot in response to the cancellation of a scheduled transport home and carried banners that read, “We Want Ships!”41 The Christmas Day protest was a sign of things to come, and they came more quickly and bigger than authorities could prepare for. The opening weeks of 1946, in fact, saw the largest wave of GI demonstrations ever to hit the U.S. military up to that time. It came on the heels of an announcement by the War Department on January 4 that there would be a further slowdown in troop demobilization; servicemen expecting to be released soon based on their number of years of service now remained uncertain of their future. The announcement touched off a chain reaction at U.S. bases around the world, beginning in the Philippines. On January 6 and 7, an estimated eight thousand to ten thousand GIs converged at City Hall in Manila and voiced dissatisfaction with the recent announcement, urging U.S. officials to scale back all overseas forces except those in Occupied Japan and Germany. On January 8, more than 3,500 enlisted men and officers at Andersen Air Base in Guam staged a hunger strike to express solidarity with those in the Philippines.42 Over the next ten days, similar actions organized by “soldier committees” took place in Hawai‘i, Le Havre, Paris, Rheims, Seoul, Shanghai, New Delhi, and elsewhere.43

The demobilization movement of January 1946 was the first concerted rebellion against the U.S. military and its growing worldwide presence. While few seemed to question the necessity of maintaining troops in Japan and Germany, in other parts of the world GIs asked probing questions about why they were needed. During Secretary of War Robert Patterson’s tour of U.S. bases in the Pacific, one soldier confronted him directly by asking, “Did you bring the 86th Division to suppress the aspirations of the Philippine people?”44 At a demonstration at Hickam Air Field in Hawai‘i, a GI and labor organizer named David Livingston stated, “We are here because there seems to be a foreign policy developing which requires one hell of a big army. It’s about time we joined with our buddies in the Philippines and said: ‘Yes, let’s occupy enemy countries, but not friendly countries.’ It doesn’t take a single soldier in the Philippines or on Oahu to wipe fascism off the earth.”45 Military officials sought to explain away the protests by attributing them to “confused and disheartened” GIs who simply wished to go home; but as the statements above indicate, GIs understood precisely what was at stake.46

More than a simple agitation to return home, the demobilization movement was part of a much wider and spontaneous anti-imperialist revolt that reverberated across the post–World War II world. During the same time, on January 24, one thousand Indian airmen of the British Royal Air Force staged a hunger strike in Cawnpore, India, against delays in demobilization and for equal pay, food, and housing conditions with British airmen. The strike lasted several days and incited a wave of similar “sit-down” strikes at British air bases in Ceylon, Egypt, and Palestine.47 While these protests were under way, a far more violent mutiny struck the British empire. On February 21, lascars of the Royal Indian Navy seized control of nine vessels off the coast of Bombay. They engaged British forces in an armed confrontation that spilled into the streets of Bombay and soon to Calcutta and Karachi, and claimed the lives of more than two hundred people. What began as strikes over equal pay and living conditions quickly turned into bolder demands, which included the withdrawal of Indian troops from Indonesia where they had been sent to help the Dutch suppress an anticolonial movement.48 These worldwide revolts told the same story: as empires scrambled to restrain the pulse of freedom in the decolonizing world, their soldiers and sailors, many of them dark-skinned colonial conscripts, refused.

Global decolonization and U.S. military expansion brought American servicemen into proximity with some of these radicalized Asian subjects, and it was the specter of their politicizing affinities that most alarmed U.S. officials. The “eyes of the world, and particularly the Japanese people, are watching with interest,” the Eighth Army’s acting commander, Lt. Gen. Charles P. Hall, warned his troops during their rebellion in Yokohama: “Subversive forces, quick to sense dissension in your ranks, will take their cue for sabotage of plans for our future action.”49 Hoyt Vandenberg had the same concern in mind when he noted in his February 1946 memo that the GI demonstrations “were not instigated on Communist Party orders emanating from the United States,” but by communists in Asia.50 These were not unfounded concerns. A year later, one counterintelligence report from the Philippines-Ryukyus Command confirmed that “there were approximately 300 American GIs, white and Negro,” who had joined ranks with the Huks in Bataan in 1946. The report went on to state that “an American GI, disguised by a long beard and dressed in old khakis, is traveling with a band of Huks” in the barrios of Tarlac Province.51

Such accounts of GI defection substantiated the worst fears of U.S. officials about the seductive dangers of international communism and illuminated a global alliance of color forged through the military. This racial menace, ironically, doubled as a military asset. During World War II, U.S. campaigns against fascism and white supremacy had demanded the inclusion of racially suspect populations into the armed services. Japanese Americans were tested for their loyalty in concentration camps to allow the “good” ones to showcase their patriotism through combat. Similarly, the Office of War Information targeted African Americans to support the war effort and to demonstrate their patriotic manhood by enlisting in the segregated military.52 After the war, the utility of racial minorities in the military would continue and expand. In September 1946, the War Department ordered the army to assign “all inductees or enlistees of Japanese ancestry” to Japan for occupation duty, where they would serve as interpreters and translators for U.S. military and civilian agencies and continue their wartime function as “ambassadors of democracy.”53 Mobilizing “race for empire” in these ways left uncertain perils for the United States in the post–World War II Pacific.

The task of monitoring these racialized subjects in the military fell to the U.S. Army’s Office of Intelligence (G-2). More than any other institution at the time, G-2 was at the forefront of producing racial knowledge about the decolonizing Pacific. Its case files of individuals, many of them rendered in great detail, hint at the complex lives of these subjects and, for some of them, even their desires to pursue a politics beyond U.S. objectives. At the same time, they also reveal the determination by U.S. military intelligence agents to diminish the very complexities of these individuals. These reports illustrate the impossible double bind in which these men and women found themselves. They were a military asset or a racial peril who invariably degenerated from one to the other.

The case of Misao Kuwaye is revealing in this sense. Kuwaye was of “Okinawan descent” from Honolulu, and had arrived in Tokyo in October 1945 as a Department of the Army Civilian Employee. She was assigned to the Press Section of the Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD), in which her primary duty was to censor Japanese mail. Kuwaye was one of fourteen “Nisei” women from Hawai‘i recruited before the war to form the CCD, and they were the first Nisei linguists to arrive in Occupied Japan.54 Kuwaye was part of this exemplary cohort and valued for her Japanese-language ability, but her employment record betrayed her talents. Soon after her arrival, the CCD discovered that Kuwaye “did not meet the qualifications as a linguist” and was, in the opinion of authorities, a “troublemaker.”55 At first, what this meant exactly was unknown, but it soon became clear.

In January 1947, military intelligence confirmed that Kuwaye had been an organizer and “a regular attendant” of the Honolulu Labor Canteen, a radical alternative to the United Service Organizations formed in August 1945 that brought together leftists in Hawai‘i, including GIs, plantation workers, and labor organizers.56 This initial discovery prompted an investigation that uncovered Kuwaye’s mobility across multiple worlds of radicalism. Subsequent reports found that Kuwaye had been “closely associated” with communists and “Communist sympathizers” in Hawai‘i, and that she had used her military assignment in Japan to build connections with radicals in Japan and Okinawa, which included members of the Japanese Communist Party and the League of Okinawans. In September, when she requested approval to transfer jobs from Japan to Okinawa, authorities found in her possession a letter from one of her associates in Honolulu urging her to obtain information about military installations on the island. On November 2, upon her return to Honolulu, customs agents confiscated “a number of documents, including press releases concerning communist activities and Japanese Women’s Suffrage,” loose pages of the Confidential Training Program for Censorship, and maps of “major cities in Japan, classified as Restricted.”57

Despite all signs of Kuwaye’s “leftist inclination,” authorities did not pursue her case further due to a “lack of conclusive proof that subject was subversive,” but her case had sufficiently alarmed officials.58 Kuwaye’s associations with leftists in Hawai‘i, Japan, and Okinawa raised questions about the loyalty of Nisei subjects employed by the U.S. Army, and it illuminated the porous boundaries of the radicalizing Pacific. The agent assigned to her case had determined, “The damage inflicted by persons of this ilk upon the occupation effort is by no means limited to their activities while in this theater [the “Far East”]. As was recently demonstrated in another case, these people return to the United States as ‘experts’ on occupation policy and set about undermining Japanese policy to any group that will listen or read their leftist ‘exposé.’” In short, the military had become a vehicle for individual and collective radicalization to undermine the U.S. empire. “The solution to this situation,” the agent concluded, “appears to be more careful investigation prior to employment and more effective means for immediate removal of such persons from employment with the occupation.”59

It was precisely this fear of subversion within the U.S. Pacific empire, even in the absence of “conclusive proof” of it, that drove G-2 to locate and determine the loyalty of Asian subjects in the military. The line between “good” and “bad” Asians never had been easy to decipher, but it nonetheless became more and more important to demarcate as the United States pursued its global war against communism. Another report on Calvin Kim, for example, revealed that the Korean American officer who was ordered to the Military Intelligence Service Language School in 1945 because of his Korean-language ability was later found to have engaged in questionable political activities, including signing two petitions in 1948 to have the Independent Progressive Party placed on the California State ballot and for an equal-housing initiative, both of which were “circulated by a known CP member.” In 1952, the army conducted a polygraph on Kim to determine his political affiliations, and the agent concluded, “There is no information to indicate that Kim has ever embraced foreign ideologies or that his racial background makes him vulnerable to Communist propaganda.” As for Kim’s earlier political involvements, “[h]e was apparently duped by the IPP in 1948, as were many politically naïve people.”60

From one report to the next, G-2 probed the political pasts of army personnel to determine their loyalty, especially those of a particular “racial background.” Another report in 1953 sought to determine if a “Charles Kim” stationed in Pusan, Korea, was the son of Diamond Kimm, the Korean leftist from Los Angeles who was then facing deportation charges for his political activities.61 Indeed, if the “foreign-born” had emerged as particular targets of the burgeoning anticommunist regime of the early 1950s, which sought to monitor and exclude “subversives” from the nation, then the army came under scrutiny for channeling in such large numbers of Asians and foreign nationals over the years. “The over-riding necessity to make maximum use of all available manpower” during World War II, a report stated in 1954, had led to “the liberalization of policy toward Communists in the Army.” Accordingly, Senator Joseph McCarthy urged the Secretary of the Army to do everything to “wee[d] out … the misfits, the incompetents, the Communists and the fellow travelers who infiltrated the Army during the twenty years of Communist coddling.”62

Determined to root out subversives hiding in plain sight, G-2 with its case files in fact accomplished something else entirely: it reinforced and reproduced the fear of racialized Asian subjects plotting against the U.S. empire. Although rare, when G-2 uncovered “conclusive proof” of actual subversion, it only confirmed the reality of this fear. The case of Yi Sa Min was one such case that elicited the intervention of the State Department in January 1950. According to the U.S. embassy in Seoul, Yi, an American citizen, traveled to Pyongyang in December as a representative of the Korean Democratic Front of North America and sought to secure the group’s membership in the North Korean Democratic Front. At a press conference, Yi stated the following: “The American people and Koreans residing [in the United States] are supporting the unified independence of Korea and her democratic development. Because we live in America, we know very well what kind of country America is and what kind of fello[w] Rhee Syngman … [is].” He minced no words as he condemned the American “invasion” of “the southern half of our fatherland,” and castigated Rhee and “his stooges” for “selling our country” to the Americans. “We will consolidate our efforts and fight for our Republic and for the unification of the North and South, and we will not permit American interference, whatever it may be.”63

To state officials, the speech lent every indication that Yi was “an active agent of the Communist-controlled North Korean regime,” and they became obsessed with his political past. As a telegram revealed, in 1919 Yi had taken part in the Korean underground independence movement in Shanghai, which led to his arrest and imprisonment for four years by Japanese authorities. Upon his release he founded the Korean Revolutionary Party and gained membership in the Korean Nationalist Association, a group “which had connections with the Chinese Communist Party.” Like many others, Yi sensed an opportunity when the United States declared war on Japan; he enlisted in the U.S. Army, served in the India and China theaters, and acquired citizenship through his military service. Earning his citizenship did little to sway his political convictions. Disillusioned by the U.S. military occupation in Korea after the war, Yi maintained associations with Korean leftists in the United States and continued to agitate for Korean independence, all while working as a Korean-language instructor in Seattle and occasionally living in Los Angeles.64 Looking back at Yi’s thirty-plus years of “communist” activities, state officials wondered how such an outlaw ever managed to slip into the military, much less to obtain citizenship. In 1950, the State Department recommended that Yi’s naturalization be deemed “fraudently [sic] obtained” and permanently revoked.65

The apparent ease by which Yi Sa Min led his dual lives as a domesticated U.S. citizen and a foreign agent confounded state officials beyond anything else. In ensuing years, it was precisely the indecipherability of these slippery categories that fueled the anticommunist persecution of Asian residents in the United States, resulting in the deportation of Filipino labor activists and the forced confessions of tens of thousands of “illegal” Chinese residents.66 But Yi’s expulsion also took place in the context of pressing geopolitical events, which renewed the question about the utility of Asians in the military. In the fall of 1949, the Chinese civil war between Communist and Nationalist forces came to a decisive end with the former declaring victory. The “loss” of China to communism stoked fears among some U.S. officials about the region’s stability, especially if China should export its revolution to Southeast Asia and Korea. The imminence of Japan’s economic collapse in 1949 compounded this scenario.67 The specter of a sweeping revolution in Asia and the loss of Japan as a regional surrogate demanded a new U.S. strategy, one that would secure the region through communist containment and economic integration.

This strategy was provided by the Mutual Defense Assistance Act, approved by Congress on October 6, 1949. The act consolidated all U.S. foreign military aid projects up to that time under the Mutual Defense Assistance Program (MDAP), appropriating $1.5 billion in aid for the first year; and in August 1950, with the Korean War in full swing, President Truman requested an additional $4 billion. Beyond the scope and price tag, MDAP’s more enduring significance rested on its conception of Pacific security. MDAP created essentially a “hub-and-spokes” security system in Asia, in which bilateral treaties between the United States and particular nation-states provided the basis for the security of the entire region. MDAP furnished new and old allied states with military equipment, economic aid, training, and technical assistance, granted with the firm assurance that an attack on one country was an attack on the United States and the “free world,” and would be met with swift retaliation.68

From the beginning, this transnational security state in Asia drew on a language of “self-help” and “mutual aid” to underscore its legitimacy as a decidedly anticolonial arrangement. MDAP granted aid to those who requested it, to give “free nations which intend to remain free” the tools to defend themselves from communism.69 On the ground, this discourse of helping Asians help themselves translated into the growing presence of U.S. military advisers that assisted with the buildup and training of national armed forces, a process that was under way in countries such as the Philippines and South Korea. In the fall of 1948, the first six Korean Constabulary officers arrived in the United States to receive training in U.S. military service schools, as part of a new training program initiated by the U.S. Military Advisory Group to the Republic of Korea (KMAG). This initial cohort was the precursor to the tens of thousands more from South Korea and other countries in Asia who did the same over the course of the 1950s through MDAP. After their training, these trainees were expected to return to their home countries, having acquired “first-hand knowledge of how Americans do things,” and to help develop and modernize their own militaries.70

In the name of promoting freedom, MDAP thus set the foundation for the United States to extend its military empire in Asia. It was a process that led to the transit and circulation of “free” Asian soldiers across the Pacific, and their arrival in the United States occurred at the precise moment when U.S. officials faced growing concerns about the presence of “subversives” in the military. Their racialized presence reproduced and magnified the threat of communist subversion even as they were hailed as the solution to curbing its global spread.

STIMULATING A “GENUINE WILL TO FIGHT”

In September 1951, through MDAP, the first group of 263 Koreans arrived in the United States. A majority of them enrolled in a special twenty-week course at the U.S. Army Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia. The official records of G-2 identified each individual by first and last name, a headshot photograph, and scant biographical information. The file on Kang Chun Gill, for example, revealed that he was born on October 15, 1928, married with no children, and an educated man, having attended primary and secondary schools in Japan as well as two years each at Hanguk University in Seoul and Taegu Normal College. Kang was “fluent” in Japanese and “fair” in spoken English, but better in reading, writing, and translating. His religion was “Protestant,” his politics, “none,” and he occupied the rank of a second lieutenant. We know little else of Kang’s life, or the lives of the other 262 trainees, for that matter.71

While G-2 divulged little, the historical record reveals that these individuals were the product of long and contentious debates among U.S. officials about the benefits of utilizing Asian soldiers. The debates began shortly after the Korean War started in June 1950. U.S. leaders knew already that the Korean War was the beginning of a much longer and wider war to secure the Asian periphery and link its economies to Japan, which in due time would embroil the United States in Vietnam. The seemingly boundless scope and geography of the war in Korea demanded flexibility and vigilance on the part of Americans. Secretary of Defense George C. Marshall told the Senate Armed Services Committee in January 1951, “We are confronted with a world situation of such gravity and such unpredictability that we must be prepared for effective action, whether the challenge comes with the speed of sound or is delayed for a lifetime.”72

Marshall’s statement echoed a broader concern among U.S. officials about the overstretched U.S. military and its state of combat readiness. With less than seven hundred thousand servicemen scattered around the globe, the prospects of waging a full-scale and effective war in Korea seemed a logistical impossibility.73 Only days after the war began, the Senate Armed Services Committee initiated hearings on a bill to create a system of universal conscription to boost U.S. military manpower. As reports came in from the front lines about the ineffectiveness of South Korean soldiers, many who apparently had fled their posts and ceased to fight, the need to build up the U.S. Army grew acute.74 “The balance of manpower is against us,” the chairman of the Armed Services Committee Lyndon Johnson remarked during the hearings in January 1951, as the induction rate reached an all-time peak of eighty thousand a month. “The grim fact is that the United States is now engaged in a struggle for survival…. Unpleasant though the choices may be, we face the decision of asking temporary sacrifice from some of our citizens now, or of inviting the permanent extinction of freedom for all of our citizens.”75

In June 1951, the Universal Military Training and Service Act passed and addressed the concern by lowering the draft age from nineteen to eighteen and extending the active-duty service commitment from twenty-one to twenty-four months, in total more than doubling the draft numbers between 1950 and 1951. The act also established the National Security Training Commission, which immediately took up the task of outlining a long-term U.S. military policy. “This solemn and far-reaching action of Congress and the President,” the commission stated in its first report to Congress, “reflects a realization, even in the heat and tension of the present crisis, that the major problems we face in the world will be of long duration, that no tidy or decisive conclusion is to be expected soon.” According to the report, the Korean War was but a phase of a global struggle that required a more or less permanent state of militarization. “The American people must be prepared, like their forebears who pushed the frontier westward, to meet a savage and deadly attack at any moment.” The frontier mythology emphasized the current threat to “free society” in a language the American public widely recognized, and the similarities could not have been more transparent. The report concluded: “The return to frontier conditions demands a frontier response.”76

In the first year of the Korean War, military and government officials experimented with this “frontier response,” reconfiguring the American military for permanent war. Beyond increasing the draft numbers, the Universal Military Training and Service Act expanded the army reserves to create a more mobile and flexible force dispersed across the globe, “capable of instantly bearing arms” to meet conflicts anytime and anywhere they occurred. At the same time, another major reform was under way that encountered far more resistance in Congress, particularly among representatives of the white South: the desegregation of the armed forces. Slow to achieve in the years after President Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which had mandated “equality of treatment and opportunity” within the armed services, the integration of African Americans in the military became official policy in 1951 as part of the solution to the growing combat-troop shortage and morale problems. “It was my conviction,” Gen. Matthew Ridgeway stated, that integration would “assure that sort of esprit a fighting army needs, where each soldier stands proudly on his own feet, knowing himself to be as good as the next fellow.”77

The demand for more bodies on the front lines made racial integration a “high priority,” and it resulted in another experiment of military integration that involved a different population.78 On August 15, 1950, as U.S. casualties in Korea continued to mount, representatives of the Eighth Army, KMAG, and the ROK Army met to discuss the possibility of incorporating Koreans into the U.S. Army. The depleted ranks left nothing to question. Two days later, before a concrete plan for procurement and training was finalized, each of the four U.S. divisions in Korea received an initial increment of 250 soldiers under the Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army (KATUSA) program. According to one report, they were “forcibly and indiscriminately recruited from the streets of Pusan and Taegu, who had received no military training whatsoever.” Some of them received “a few weeks” of basic training, others were promptly assigned to units and trained just prior to being sent into combat. By November 1950, 22,000 Korean soldiers were integrated into the Eighth Army.79

The KATUSA program was part of a longstanding colonial practice of incorporating “native” troops into the imperial army. The Philippine Scouts, organized at the start of U.S. colonial rule as a separate organization of the U.S. Army, served as a direct blueprint. As with the Scouts, KATUSAs occupied a liminal position as “not technically a part of the U.S. Army,” but who nonetheless filled the ranks as an intermediary who could gather intelligence and impart knowledge about the local terrain and population. Their language and cultural difference drew the ire of their American counterparts. “The ROK soldiers were unable to understand even the simplest command,” according to one report. Their lack of “understanding of field sanitation and personal hygiene,” and their general unfamiliarity with “U.S. conceptions of everyday living,” including rations and clothing, turned them “from a welcome asset to an irksome burden.”80

Military officials with no firsthand experience of these limitations sang praises for the KATUSA program, especially with their sights set on the future. In their view, the program gave Korean soldiers “sorely needed training in U.S. methods and techniques,” and thus provided “a U.S.-trained cadre for the postwar Korean Army.” The program proved useful even beyond the Korean context. As officials understood, KATUSA was an experiment in “military efficiency” that could inform how the United States conducted its future global conflicts. “The United States may well again be faced with the possibility or necessity of augmenting the U.S. Army with native troops,” according to an operations research study conducted in 1953. As Asian nations became formally decolonized, the Pacific region emerged as a laboratory to experiment with various methods of incorporating “native” manpower into the U.S. military. “Future military operations in underdeveloped parts of the world,” the 1953 study affirmed, would “unquestionably involve the use and support of native armies.”81 This idea, I show in later chapters, led to military experiments throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

Since the start of the Korean War, Secretary of the Army Frank Pace Jr. realized that a state of permanent war would require the mobilization of non-U.S. populations. In November 1950, as the integration of KATUSAs progressed at a peak rate, Pace requested Vice Chief of Staff of the Army Gen. Wade Haislip to conduct a study, as “a matter of urgency,” of the possibility of using “foreign nationals to build up the strength of our forces in critical areas overseas” beyond Korea. In his request, Pace referenced the Lodge Act that had been enacted earlier in June, which allowed for the overseas recruitment of “aliens” into the U.S. armed forces. This act only applied to the countries of Western Europe, however, and recruited subjects who were “eligible to citizenship” (hence, racially “white”), thus rendering it ineffective and irrelevant in the “Pacific Area.”82 In light of the current war in the Asian rimlands, Pace advocated that the army increase the number of aliens in the armed forces “to a much greater figure,” including the possibility of organizing Japanese nationals into separate combat units.83

Two weeks later, Haislip and his staff responded by publishing a study that outlined different methods of mobilizing foreign manpower, including the enlistment of “displaced persons, defectees and potential defectees from unfriendly countries” into the U.S. Army. The study also suggested the possibility of organizing alien service members into separate units for “unconventional” warfare.84 Its range of ideas prompted further consideration by the National Security Council, which issued its policy paper on the subject in April 1951. NSC 108, as the policy was designated, spelled out the problem with a language similar to that used to justify Universal Military Training: “The United States should seek urgent improvement in the utilization of foreign manpower for military purposes in order to increase the flexibility of employment of our own military forces and to avoid a disproportionate contribution of the United States manpower to the over-all military posture of the free world.” Taking a global view, the policy crunched some remarkable numbers: the availability of “physically fit” 15- to 49-year-old men from countries “favorably disposed toward the United States” stood at 130 million, roughly 17 million more than those in the “Soviet bloc.” The mobilization of this vast pool of foreign manpower would bolster the overall military capability of the “free world” to act as an effective bulwark against “Soviet expansionism.”85

By calculating the ways that foreign manpower could be mobilized, NSC 108 worked as a sort of addendum to the Universal Military Training and Service Act that was enacted two months later. But beyond increasing manpower and improving “military efficiency,” the utilization of foreign soldiers served a broader cultural function. The policy made clear that part of the goal of mobilizing these subjects was “to stimulate a genuine ‘will to fight’ by the winning of men’s minds and the build-up of resistance to communist ideology and propaganda.” The National Security Council insisted cultural diplomacy and military buildup were complementary projects, it was something that Soviet leaders had pursued for some time by recruiting soldiers from the “Soviet bloc,” and Americans needed to catch up and do the same. “We have more to sell, but [the Soviets] have been the better salesmen to date.”86

The dual imperatives of “selling” democracy and mobilizing foreign military labor, however, opened the United States to the charge of employing mercenaries, which threatened to undermine American credibility. As General Haislip and his personnel staff cautioned, the use of mercenaries by the United States would be “repugnant to the ideals of our people, would leave us open to the charge of ‘imperialism,’ and give substance to the charge of our enemies that we intend to hire others to fight for us.” The French Foreign Legion, “composed mostly of aliens” and French colonial subjects, had drawn the indignation of world opinion precisely for this reason. Haislip and staff pointed out that even “our own Philippine Scouts,” America’s most recent experiment with a mercenary force, had responded to their “inferior pay and allowances” with a “minor mutiny” in 1924.87 The times were no longer amenable to such practice. As both the National Security Council and the army personnel staff underscored, the United States must distance itself from “imperialism” and make a clear stance for “freedom.”88

NSC 108 thus concluded the “most effective utilization of foreign manpower” rested on the development of the “armed forces of free nations,” a process already under way through the MDAP. Specifically, this entailed a practice that the Department of Defense (DOD) termed “mirror imaging,” in which U.S. training and doctrine, force structure, and supplies and equipment were exported and imposed on the organization of allied forces. Mirror imaging essentially was “modernization” theory applied through the military, in the sense that it approached the military as a vehicle for transforming “backward” countries into thriving nations oriented toward capitalism.89 Lt. Gen. James Van Fleet, Commander of the Eighth Army who was credited with turning around the lackluster Korean army during the war, understood his role within this framework. In the spring of 1951, he arrived in Korea and found the ROK Army in a shambled state but also saw Koreans “anxious to fight for their freedom.” The “Orientals apply themselves intensely,” he commended, “tell them something once, and they have it,” but all their individual motivation was squandered without the “competent leadership” of Syngman Rhee. In the end it was the leader of the republic, not the leader of the Eighth Army, who could command their allegiance. Once Rhee realized this fact and acted on it, the men of the ROK Army “suddenly were transformed into soldiers.”90

In the end the processes of turning “boys” into soldiers and transforming a colony into a modern nation were one and the same. Both depended on the ability of Asians to defend themselves from communism, the threat to their newfound freedom. Van Fleet was convinced that “Asia can and should be saved by Asians,” and it could be done precisely by teaching Asians how to embody martial citizenship through the mirror imaging of their national armed forces. Doing so would save American manpower and dollars as well as “strip the Communists of their powerful argument that ours is no real war for freedom but only a white man’s ‘imperialist’ war to put Asia in chains.”91 MDAP was, in this sense, an imperial projection of anticolonial self-determination. It produced foot soldiers for the U.S. empire and provided an arsenal for the propaganda war with the Soviet Union.

In 1950, the DOD began to select and send foreign military trainees to U.S. service schools through MDAP, the cream of the crop of allied forces who would take the lead in America’s “real war for freedom.” In the first year, MDAP brought students from 14 countries, with each country committing between 22 and 627 students. Initially, most of the students came from so-called “Title I” countries, the nine European countries receiving the biggest portion of MDAP grants owing to their proximity to the “Iron Curtain.” But by 1959, of the more than 140,000 foreign nationals who passed through the United States, 58,203 came from Asia. South Korea and Taiwan sent 14,445 and 15,552 students, respectively, the highest numbers among the total 54 countries. U.S. officials saw these students as military assets. In 1962, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara reflected on the long-term benefits of MDAP: “In all probability the greater return on any portion of our military assistance investment—dollar for dollar—comes from the training of selected officers and key specialists in U.S. schools and installations.”92

U.S. military officials saw these foreign trainees in instrumentalist ways and assessed their value through a cost-benefit analysis. As one KMAG officer put it, MDAP training program amounted to “a package plan to provide maximum instruction at the least possible expense in the least possible time.”93 But aside from serving purely military purposes, these trainees also embodied a story of progress that affirmed the modernizing potential of Asian soldiers and, in turn, the military’s potential as a vehicle of modernization in Asia. Toward this end, in 1951, the State Department and the DOD collaborated on a series of projects highlighting the MDAP trainees as conduits of democracy. Aimed at audiences abroad, they developed “hometown type stories” presumably about the trainees’ immersion in the local communities and produced a motion picture titled Forces of Freedom.94 By the decade’s end, their efforts would maximize the “collateral benefits” of training these foreign students, and hone their potential as “a multi-purpose cold war weapon” that served “political, economic, and social, as well as military” purposes.95 Their efforts cohered in a cultural industry for the military.

Molding these trainees for U.S. cultural diplomacy was a two-way process that involved shaping their experiences in the United States as well. The DOD aimed to do this by producing a “guidebook” to acquaint the trainees with various aspects of American culture and society. The 1959 guidebook began with the preface: “We welcome you to the United States and we welcome the opportunity to share with you not only our professional military skills, but our hospitality and our way of life.” What followed was a fifty-five–page distillation of the “American way of life,” covering topics such as military customs, standard of living, diet, etiquette, and “the American Character” marked by freedoms of the press and religion, and by the “enterprising individual.” The guidebook worked to preempt the visitors from forming their own negative understanding of U.S. “social problems.” It explained that “prejudice against minority groups is a problem in the United States just as it may be in your own country. Although you have probably read or heard of incidents of discrimination against Negroes in certain sections of the United States, bear in mind that discrimination is not confined to Negro Americans. Wherever a minority racial, cultural, or religious group exists, it may be the object of discriminatory practice.” The guidebook suggested “prejudice” was a universal phenomenon owing to “group” differences rather than an inherent defect of American society.96

The DOD guidebook’s sanitized narrative of American life further translated into concrete experience for the trainees through social programs. The Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, for example, started an Allied Officer Sponsor Program in 1959 to “promote [the] cultural and social integration of Allied students” by pairing them with an American officer who would “act as personal friends” and guide them through their time at the college.97 A “Hospitality Program” at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center attempted the same by encouraging local navy families to invite students into their homes “for visiting and informal dining.” These programs, no matter their origins, characterized the task at hand as a “unique opportunity” to promote one-on-one relations, “to help acquaint these men with America and Americans [and] plan[t] the seeds of real friendship and understanding.”98 A New York Times editor confirmed these positive attributes of the training program by quoting the words of one Korean trainee in his letter to a friend back home: “Until I saw America and talked and associated with Americans I doubted if what I heard about America was true; I know that there can be, and we can have, the same freedom of religion, speech, and press in our own country and in this whole human world.”99

Efforts to shape the perceptions of the military trainees invariably cracked at the seams. No number of guidebooks or sponsorship programs could keep the trainees from witnessing the blunt realities of the American color line, or from pursuing desires beyond the military lives imagined for them. For example, Pak Chŏngin, a division commander who studied at Fort Benning, recalled seeing “the discrimination against Negroes in the Southern region,” which he found “terribly distasteful.”100 Given the value placed on these MDAP trainees as cultural diplomats, the inability of U.S. government and military officials to control their negative perceptions of life in the United States had the potential of backfiring irreparably. Although the historical record does not show these subjects returning to their home countries politicized by their experience abroad, it does reveal how they posed a problem of an entirely different kind, one that officials had not foreseen: their desertion and subversive mobility in the United States.

SEEKING ASYLUM IN THE TRANSNATIONAL SECURITY STATE

No individual did more to confound the MDAP training program in the 1950s than Hsuan Wei, the subject who opened this chapter and who came to symbolize the unintended and undesirable consequences of U.S. militarization. By orders of the U.S. Navy for military training in September 1952, Wei arrived in the United States, and from 1952 to 1954 he attended a total of three courses at the Marine Corps School in Quantico and the Amphibious Base in Little Creek, Virginia. He completed his training with honors on June 4, after which he received orders to fly to San Francisco. From there, he would report to the staff headquarters of the Twelfth Naval District and await transportation to Taiwan. On June 8, he proceeded as directed, and was cleared for departure three days later. When his plane departed, however, Hsuan was nowhere on board. An immediate investigation revealed that he had checked out of his hotel with all of his belongings. No foul play was suspected. Instead, naval authorities seemed to know without a question of doubt that Wei had gone AWOL. The investigation and endless confusions that followed were beyond anything that officials could have imagined at that moment.101

A national manhunt ensued over the next few weeks, coordinated among Chinese authorities and U.S. Navy and immigration officials. Wei, meanwhile, had sought temporary refuge in Evanston, Illinois, where he enlisted the legal aid of K.C. Wu, the ousted governor of Taiwan Province known for his staunch criticisms of the Chinese Nationalist government. Two months prior, Wei had made contact with Wu, expressing his growing disillusionment with Chiang Kai-shek’s regime.102 On Wu’s advice, two weeks after his disappearance, Wei wrote a letter to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) office in Washington, D.C. that revealed his whereabouts. This move was a shrewd political strategy. In the letter, Wei invoked section 243(h) of the Immigration and Nationality (McCarran-Walter) Act of 1952 and the Refugee Relief Act of 1953. He requested political asylum and expressed his wish to stay in the United States for fear of persecution back home. The letter announced his defiance against Chiang’s government, at once removing his taint as a deserter by proclaiming himself an asylum seeker.103

On July 3 in Skokie, Illinois, U.S. naval authorities apprehended Wei and escorted him back to San Francisco, determined to return him to Taiwan immediately. But his request for asylum posed complications that the navy could not ignore. On July 7, while Wei remained in custody at the Twelfth Naval District, the State Department’s Director for Chinese Affairs, Walter P. McConaughy, convened a meeting with other state and navy officials to discuss possible actions toward his deportation. The meeting generated a sea of confusion about whether Wei should be deported through immigration or military channels, and concluded with no agreement. According to the state legal advisers, the navy was not “legally empowered” to remove him from the country, “no matter how politically desirable such action might be.” Joseph Chappell, the assistant director of the Visa Office, expressed the willingness of the INS to “look the other way” while the navy deported Wei. He admitted this had been done in past cases involving other attempted desertions by foreign trainees, but the state legal advisers could not verify this claim. They cited their own recollections that such cases “had been handled under regular deportation procedure.”104

This discussion revealed the fundamental newness of the problem Wei’s case presented. The uncertainty of whether Wei should be deported by the INS or the navy drove officials in endless circles. Hsuan Wei defied simple dichotomies—he was both a political problem and a military problem, yet there was no remedial means for handling both. The meeting ended with an agreement to consult more MDAP and INS officials.105 That same day, the Chinese naval attaché drew a more definitive conclusion about Wei’s case: “Hsuan’s motivation was believed to be selfish rather than political,” he stated, and “if he succeeded in his effort to abandon his post of duty and start an easier life in this country, other defections of Chinese military officers in similar circumstances could be anticipated, with serious prejudice to Chinese military discipline and to the Mutual Defense Assistance Program.”106

Concerns about the possible ripple effects of Wei’s “selfish” act were not misguided. In the following years, as Wei battled his way through lengthy court hearings and appeals to remain in the United States—in the process capturing the media spotlight and winning legions of supporters around Chicago where he continued to reside—the State Department confronted a handful more cases involving Chinese military deserters who filed for asylum and whose cases shared many other similarities.107

Wei’s subversion defied easy categorization; he was neither a “Communist agent” like Yi Sa Min nor a subject who espoused “leftist inclinations” like Misao Kuwaye or Calvin Kim. Quite the contrary, Wei was an avowed “anti-Communist” who wanted nothing more than to see the communists driven out of his homeland. Nonetheless, he threatened the government because his decision to go AWOL and remain in the United States occurred at the precise junction of two overlapping forces: the U.S. militarization of Asia that depended on his labor as a military and cultural asset, and the anticommunist purge that deemed his “foreign” presence in the United States a threat to national security. That he was caught between these imperatives was not a coincidence. Instead, it revealed the contradiction at the heart of the U.S. empire in an age of decolonization: that the impulse to militarize and liberate Asia from communism reproduced and magnified the very problem of subversion it sought to contain.