Читать книгу Peace and Freedom - Simon Hall - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

In February 1966, world heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali was in Miami, training for his title defense against Ernie “the Octopus” Terrell. One afternoon a television reporter sought Ali’s reaction to the news that the Louisville Draft Board had upgraded his draft status from 1-Y to 1-A, thereby making him eligible for immediate induction into the United States Army. Ali’s retort, “I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong,” helped define an era. Fourteen months later Ali refused induction, explaining “I am not going ten thousand miles from here to help murder and kill and burn another poor people simply to help continue the domination of white America.”1 Ali’s response to the war in Vietnam seemed to many to epitomize a new militancy within Black America. The October 1966 platform of the Black Panther Party demanded that all African Americans be exempted from military service—“Black people should not be forced to fight … to defend a racist government that does not protect us.” The Panthers refused to “fight and kill other people of color who, like black people, are being victimized by the white racist government in America.”2 Stokely Carmichael and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) attacked the war too. Speaking at one antiwar march, Carmichael defined the draft as “white people sending black people to make war on yellow people to defend land they stole from red people.”3

It was not just black militants who were critical of America’s actions in Vietnam. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the nation’s most important and most respected civil rights leader, also condemned the war in the strongest possible way. In the spring of 1967, King bitterly denounced the “madness of Vietnam” and called on his government to take the initiative in halting the conflict.4 Indeed, by the time that the Paris Peace Accords were signed in January 1973, every major civil rights leader had spoken out against the war.

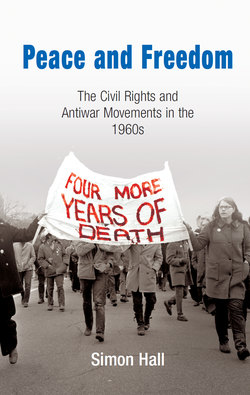

The years between 1960 and 1972 saw the emergence of two of the most significant social movements in American history—the African American freedom struggle and the movement to end the war in Vietnam. This book sets out to offer a detailed analysis of the relationship between them, by exploring two key themes.

First, the response of the various civil rights groups to the war is documented and explained. Although a large number of civil rights groups opposed the war early on—including SNCC, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the civil rights movement was far from united in its reaction. Important organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Urban League did not initially support civil rights groups speaking out against the war and did not adopt antiwar positions until the end of the 1960s.

Second, the nature of the relationship between antiwar civil rights organizations and the mainstream peace movement is analyzed. On the surface there were good reasons why they should have cooperated closely: many early white opponents of the war were veterans of the civil rights movement; African Americans had powerful reasons to oppose the war in Vietnam; and the two movements shared a similar critique of American society. For a variety of reasons, though, a meaningful coalition was never constructed. Nothing better illustrates this than the fact that at both the 1967 March on the Pentagon and the demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, two protests that have come to symbolize the peace movement in the popular imagination, African Americans were conspicuous by their absence.

Any account of the relationship between the peace and freedom movements must acknowledge the historical background to this story. From the abandonment of the freed people by Republicans during Reconstruction through to the present, the relationship between Afro-America and white radicals has rarely been straightforward. With regard to the modern black freedom struggle, the 1930s saw widespread cooperation between white leftists and the nascent civil rights movement. The U.S. Communist Party (CPUSA) took the lead, becoming a fierce opponent of racism and a champion of civil rights. This commitment was epitomized by their vigorous defense of the Scottsboro Boys—nine blacks who were falsely accused of raping two white women on a freight train in Alabama in 1931. But despite their courageous stands on civil rights and bold advocacy of racial justice, Communists proved to be less than reliable allies—often because of their propensity to switch policy dramatically at the request of the Kremlin. Even their involvement in Scottsboro was controversial. The NAACP, for example, believed that the CPUSA was more interested in discrediting the American legal system and recruiting new members than in actually securing the release of the black plaintiffs. The Communists, meanwhile, condemned the NAACP as “bourgeois misleaders.”

During the Popular Front period (1934–1939), when the CPUSA made common cause with the non-Communist left, tensions between black activists and Communists continued. The National Negro Congress (NNC), a coalition of almost every important black group in America, represented a “coming together of left-wing radicalism, labor militancy, and heightened racial consciousness,” according to Adam Fairclough. Set up in 1936, it was headed by Asa Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first all-black union. But he resigned in 1940 in protest at Communist manipulation of the NNC and their efforts to secure its opposition to U.S. entry into World War II. Indeed, the CPUSA’s U-turns on the war following the Nazi-Soviet Pact and then the launch of Operation Barbarossa caused many former allies, white and black, to view Communists as little more than incorrigible cynics. Nevertheless, there had been signs of black-white tension within the Congress before Communist manipulation came to the fore. In his inaugural address Randolph had welcomed white support, but noted that “in the final analysis, the salvation of the Negro … must come from within.” This was a theme that he returned to when organizing his March on Washington in January 1941 to oppose racial discrimination in the armed services and defense industries. Believing that “all oppressed people must assume the responsibility and take the initiative to free themselves” he restricted the effort to blacks only. Another reason for excluding whites was to reduce the chance of Communist manipulation.5

There were other leftists and non-communist socialists who appealed for black support and responded to black needs during the New Deal era. In 1932 Myles Horton, a graduate of New York’s Union Theological Seminary, founded the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. Dedicated to promoting the tenets of grassroots, interracial democracy, Highlander produced two generations of civil rights and labor activists and symbolized the best about relations between black activists and white leftists. Organized labor also became increasingly responsive to black concerns during this period and made big efforts at unionizing black workers—for pragmatic as well as ideological reasons (white employers frequently used blacks as strike breakers). The militant trades unions of the Congress of Industrial Organizations—especially the United Auto Workers, led by Walter Reuther, and John L. Lewis’s United Mine Workers, which organized workers without respect to race—were particularly appealing to blacks. The civil rights movement’s increasing orientation toward the labor movement was most clearly indicated in 1941, when NAACP executive secretary Walter White traveled to Detroit to rally black support for a UAW strike against the Ford Motor Company. Nevertheless, white working-class racism remained a significant obstacle to interracial unionism, and many of the CIO’s southern leadership were reluctant to attack Jim Crow—due both to personal prejudice and a desire not to alienate white workers.6

Despite McCarthyism’s decimation of the legacy of the interracial leftist activism of the 1930s and 1940s, this prehistory is important. While the experiences of the New Deal era showed that interracial cooperation on the American left was both possible and potentially fruitful, it also revealed the problems and obstacles that existed. These problems—black fears of cooptation by white leftists; concern that whites sought black support merely to legitimate their own radicalism; and the sense of whites as potentially unreliable allies—would all characterize the relationship between the peace and freedom movements during the sixties.

The civil rights movement’s response to the Vietnam War and its relationship with the peace movement was also shaped by the historic links between the black movement and American pacifism. Although not all black critics of the war were pacifists, some of the earliest and most prominent were—or else held a deep commitment to the philosophy of nonviolence. Though a product of a number of factors the antiwar positions of people like James Farmer (CORE), Bob Moses and John Lewis (SNCC), and Martin Luther King were shaped by pacifism and Gandhianism. While historians such as Tim Tyson have shown that perceptions of “the civil rights movement” as wholly nonviolent are simplistic, the black freedom movement of the 1950s and early 1960s tended to use nonviolent direct action as its weapon of choice, and did so to great effect. Moreover, there were a number of important organizational and personal links between the black movement and American pacifism. Activists with the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), for example, founded the Congress of Racial Equality in 1942. FOR, a nondenominational body that rejected violence and war, was headed by Abraham J. Muste—a six-foot tall, gaunt, thin, one-time Communist turned dedicated Christian pacifist. Muste became a key figure in the 1960s peace movement. CORE’s leader in the early 1960s, James Farmer, had helped found the organization while race relations secretary with FOR. A man of “robust physique” who “spoke with the resonant tones of a Shakespearean actor,” Farmer refused to fight in World War II (he was granted a draft deferment). He also helped pioneer the application of Gandhian tactics to the civil rights struggle—launching a number of sit-in protests in Chicago during 1942, for example. Farmer himself represents the intersection of the pacifistic and leftist traditions within black America, and also offers a link with the New Left of the 1960s. As well as opposing World War II, Farmer briefly worked for the League for Social Democracy—a non-communist, pro-union social democratic organization. During his tenure as student field secretary, he worked for the Student League for Industrial Democracy, the forerunner of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the most influential radical student organization of the 1960s.7

SNCC was one of the most militant civil rights groups of the 1960s. Founded at Shaw University in April 1960, it engaged in grassroots organizing in an attempt to nurture indigenous black leadership and build community institutions. Its young organizers, fired by a faith in the ability of ordinary people to make their own decisions and committed to interracial cooperation, sought to build the “Beloved Community” in some of the most inhospitable areas of the Deep South. Like CORE, SNCC had strong links with the pacifist movement. James Lawson, who helped draw up the organization’s founding statement—a searing advocacy of Christian love and redemptive nonviolence—had chosen prison rather than military service during the Korean War. He subsequently became FOR’s first southern field secretary. In the late 1950s he played a vital role in stimulating nonviolent civil rights activism in Nashville. Bob Moses, an icon of the civil rights movement and leading SNCC activist was another who had moved in pacifist circles. At the end of his junior year at New York City’s Hamilton College he had worked at a European summer camp sponsored by the pacifist American Friends Service Committee. Moses was also influenced profoundly by existentialism—particularly Albert Camus’ emphasis on the need to cease being a victim without becoming an executioner.8

Although his political odyssey during the 1960s took him toward the right, in the 1950s Bayard Rustin, like Farmer, represented the intersection of the leftist and nonviolent traditions within the black movement. Rustin, a man of athletic build (he had been a high school track and football star) with a deeply moving tenor voice, had been raised by his maternal grandparents in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where he was heavily influenced by his grandmother’s Quaker beliefs. Rustin, who became a sincere pacifist himself, had been a member of the Communist Party in the 1930s, remained a disciple of black labor leader A. Philip Randolph, and at various times worked for FOR and the War Resisters League. His pacifism led to his resignation from the Communist Party in 1941 when it supported World War II, and also resulted in him serving time in prison as a conscientious objector.

Rustin, an intellectual, raconteur, and keen collector of antiques, became an important force within the civil rights movement. Although his conviction on a “morals charge” (he was caught having sex with two men in a car in Pasadena) meant that he was excluded from public leadership, Rustin exerted considerable influence behind the scenes. For example, during the Montgomery Bus Boycott he helped tutor Martin Luther King in nonviolent philosophy, and he was the organizational mastermind behind the awesome 1963 March on Washington, at which King delivered his “I have a dream” oration.9 Moreover, through his friendship with Tom Kahn, one of the few white undergraduates at Howard University and a member of its Nonviolent Action Group, Rustin acted as mentor to a number of activists who would play important roles in SNCC. These included Stokely Carmichael, Charles Cobb, Courtland Cox, Ruth Howard, and Mike Thelwell. Carmichael in particular was impressed by Rustin’s ability to link social democratic politics with the struggle for black rights.10

Other important links between pacifism and the black movement included Liberation Magazine, a journal edited by David Dellinger, a pacifist and future anti-Vietnam War movement leader (Rustin was a coeditor). In the 1950s Liberation offered its support to the civil rights movement, publishing the first piece of political journalism to carry Martin Luther King’s byline. Moreover, many of the civil rights movement’s earliest white supporters came from pacifist circles. A number of white participants in the Freedom Rides of May 1961, for example, were veterans of the pacifist movement.11 Attempting to build links between the 1960s peace movement and the civil rights movement, then, at one level represented a return to the movement’s pacifist roots, and provided at least some common ground on which to construct a coalition.

Frequently portrayed as excessively patriotic in its support for American foreign policy, black opposition to the war in Vietnam has often been viewed as representing a major break with the past. W. E. B. Du Bois’s 1918 exhortation calling on blacks to forget their “special grievances” and “close ranks” with white Americans and the allied nations in support of World War I has been seen as representative of black attitudes toward U.S. foreign policy. But this represents at least a partial misreading of history.12 Indeed, the twentieth century witnessed frequent fierce black criticism of American foreign policy. Gerald Horne, for example, has argued that African Americans “have been among the vanguard of anti-imperialism and militant political activity.”13 Far from representing a break with the past, black leaders’ responses to Vietnam were part of a long tradition of critical engagement with U.S. foreign policy.

Between 1915 and 1920, for instance, the NAACP opposed American military involvement in Haiti—the world’s first black republic. Following a detailed investigation by the Association’s executive secretary, James Weldon Johnson, the NAACP demanded a withdrawal of American troops, and suggested that American policy toward Haiti was racist.14 In the 1920s, Garveyism linked black American progress with a strong and independent Africa, and Garvey himself urged African Americans to fight for Africa, not America.15

The 1930s and 1940s saw much criticism of colonialism by black organizations and leaders. Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 generated particular condemnation. On August 3, 1935 approximately 25,000 blacks attended a rally in Harlem organized by the Provisional Committee for the Defense of Ethiopia, a popular front group. The rally’s sponsors included A. Philip Randolph, Lester Granger of the Urban League, and the NAACP’s Roy Wilkins.16 Many blacks were also active in popular front activities in support of the Republicans in Spain. In Harlem, the American League Against War and Fascism organized a number of peace marches and conferences in the spring of 1937. Once again Roy Wilkins joined a host of other black activists in supporting popular front actions, believing that African Americans had much to gain by working in anti-fascist organizations that were sensitive to civil rights.17 By the mid-1940s, the NAACP’s opposition to colonialism was strong. Along with the National Negro Congress it had signed the “Declaration by Negro Voters,” calling for an end to imperialism and colonial exploitation.18 In March 1946, NAACP executive secretary Walter White warned that blacks were “determined once and for all to end white exploitation and imperialism.”19 Moreover, throughout the 1940s and early 1950s the pages of the Association’s magazine, The Crisis, often contained articles attacking Western colonialism and empathizing with liberation struggles throughout the Third World.20

Although black America exuded patriotism during the Second World War, attempts were made to use war abroad to gain racial progress at home—the so-called “Double-V” campaign.21 While the NAACP supported the war against Nazism it, along with A. Philip Randolph’s March on Washington Movement also pushed for reforms such as fair employment practices and the desegregation of the military.22 This tactic of placing demands for civil rights within a wider framework of patriotism and national service—a tactic that had been used by blacks since the founding of the nation—would remain an important model for the civil rights movement, particularly during the early Cold War.

Though the Cold War was originally seen as a total disaster for the civil rights movement, in recent years a rich scholarship has emerged that reconsiders its impact on black America. Historians such as Thomas Borstelmann, Mary Dudziak, Azza Salama Layton, and Penny Von Eschen have shown how the Cold War offered new opportunities to civil rights activists as well as presenting them with new problems.23 It is clear that McCarthyism generated powerful pressures on black organizations to embrace anticommunism or perish. The NAACP therefore quickly softened its stand on anticolonialism and became a firm supporter of anticommunist measures, domestic and foreign. Those civil rights organizations and activists that did not take such steps, such as the Civil Rights Congress, the Southern Conference Educational Fund, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Paul Robeson were either destroyed or incapacitated as a result.24

Nevertheless, at a time when America was championing the cause of world freedom and attempting to win the hearts and minds of recently decolonized third world peoples, the Cold War offered black leaders new opportunities to press for racial progress at home. Civil rights leaders were well aware that domestic racism was an international embarrassment that threatened to undermine America’s Cold War mission, and they attempted to use this situation to their advantage by pressing for change at home in order to better fight Communism abroad. America’s leaders responded by granting some important concessions.25

Some black leaders, however, went beyond this to make broad criticisms of what they viewed as American imperialism. Malcolm X, for example, repeatedly urged African Americans to internationalize the struggle by taking their grievances to the United Nations. It is not surprising, then, that Malcolm was a fierce critic of the war in Vietnam. He believed that the war and domestic racism were related, and he linked the oppression of African Americans with the use of military force against people of color in Asia. Malcolm declared that “this society is controlled primarily by racists and segregationists … who are in Washington, D.C., in positions of power. And from Washington, D.C., they exercise the same forms of brutal oppression against dark-skinned people in … Vietnam.”26

Malcolm’s views on the war echoed those of Paul Robeson, who in 1954 had condemned American policy toward Vietnam as racist. For Robeson, whose support for the Communist Party line on most issues was well known, Ho Chi Minh was the Toussaint L’Ouverture of Indo-China, and he wondered aloud whether “Negro sharecroppers from Mississippi” would be sent to “shoot down brown-skinned peasants in Vietnam—to serve the interests of those who oppose Negro liberation at home and colonial freedom abroad?”27 Speaking shortly before his assassination, Malcolm declared that Vietnam, Mississippi, Alabama, and Rochester, New York, were all victims of racism.28 It was a view that would increasingly be accepted by both the white New Left and the radical black movement.

While Martin Luther King was in many ways less radical than either Malcolm X or Paul Robeson, and tended to engage with the Cold War simply to gain concessions for blacks at home, there is some evidence of the radicalism that characterized his later opposition to Vietnam. In May 1961, King was asked for his reaction to the Bay of Pigs debacle in Cuba. He declared that “For some reason, we just don’t understand the meaning of the revolution taking place in the world. There is a revolt all over the world against colonialism, reactionary dictatorship, and systems of exploitation.” King continued, “unless we as a nation … go back to the revolutionary spirit that characterized the birth of our nation, I am afraid that we will be relegated to a second-class power in the world with no real moral voice to speak to the conscience of humanity.”29 King went on to state that he was as concerned about international relations as he was about the domestic civil rights movement.30

In early 1965, as the climactic battle of the civil rights movement was unfolding in Selma, a Cold War conflict came to the fore that would have profound consequences for America. The United States had been sending military advisors to South Vietnam since 1959, having previously supported France’s attempt to regain control of her colony. But American involvement increased rapidly after Lyndon Johnson’s election in November 1964. The bombing of North Vietnam, which began in February 1965, was followed by the deployment of American ground forces. In early March, two battalions of marines were placed near Danang to defend an air base, and by the middle of June there were approximately 50,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam. The number would more than double by the end of the year.31 By then, important civil rights groups and leaders, including SNCC, CORE, and King, would either have opposed the war, or signaled extreme unease over it.

African Americans certainly had good reasons to oppose the war in Vietnam. With their racial consciousness raised by the civil rights movement, many blacks wondered why they should fight abroad for a nation that still denied them first class citizenship. As Martin Luther King explained, “we have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools.”32 SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael urged blacks not to fight since they were denied freedom at home, and went so far as to term black soldiers mercenaries. He explained that a “mercenary will go to Vietnam to fight for free elections … but doesn’t have free elections in Alabama…. A mercenary goes to Vietnam and gets shot … and they won’t even bury him in his own home town.” Carmichael concluded, “we must … when they start grabbing us to fight their war … say, ‘Hell no’.”33 Many civil rights activists argued that, rather than fight in Vietnam, African Americans should instead be focusing their energies on the struggle for change in America.34

A second objection to the war derived from the discriminatory nature of the draft. It was not unknown for the Selective Service System to give black militants and civil rights organizers “special attention.” In January 1966, for example, the Selective Service announced it was reviewing the Conscientious Objector (CO) status of SNCC’s John Lewis because of his recent antiwar and antidraft statements.35 Mississippi native James Jolliff, an epileptic, found his classification upgraded from 4-F to 1-A after he became president of his local NAACP chapter.36 The Selective Service also drafted blacks in disproportionate numbers. In the early years of the war African Americans accounted for more than 20 percent of all draftees, despite making up just 10 percent of the U.S. population.37 A mentally qualified white inductee was 50 percent more likely than a mentally qualified African American to fail his pre-induction physical in 1966, and the following year 64 percent of eligible blacks were drafted compared with 31 percent of eligible whites.38

At the same time, there were almost no African Americans serving on draft boards. In 1966 blacks made up just 1.3 percent of total draft board membership. Some board members were staunch racists. Jack Helms, head of the largest draft board in Louisiana, was a Grand Dragon in the Ku Klux Klan.39 In 1968 the chairman of Atlanta’s draft board referred publicly to former SNCC activist Julian Bond as a “nigger” and expressed regret that he had not been drafted.40 This was not lost on black activists as they formulated their response to the war. SNCC’s Walter Collins, for example, denounced the draft as a “totalitarian instrument used to practice genocide against black people.”41

The fact that America was waging war on a non-white people also caused a good deal of concern among many black Americans. Increasingly, black activists took the position that the war was itself racist. In a posthumously published essay Martin Luther King declared that America’s “disastrous experiences in Vietnam … have been, in one sense, a result of racist decision-making. Men of the white West, whether or not they like it, have grown up in a racist culture, and their thinking is colored by that fact…. They don’t really respect anyone who is not white.”42 Carmichael also linked the war to a version of white paternalism that was remarkably similar to King’s analysis. He explained that “we are going to kill for freedom, democracy, and peace. These little Chinese, Vietnamese yellow people haven’t got sense enough to know they want their democracy, but we are going to fight for them. We’ll give it to them because Santa Claus is still alive.”43 Many black Americans developed a sense of racial solidarity with the Vietnamese, as illustrated by the comments of one SNCC fieldworker who stated “you know, I just saw one of those Vietcong guerrillas on TV. He was dark-skinned, ragged, poor and angry. I swear, he looked just like one of us.”44

Other reasons for African Americans and the civil rights movement to oppose the war in Vietnam included the commitment to the philosophy of nonviolence. Martin Luther King explained that it was becoming impossible for him to speak out against violence in the ghettos whilst refusing to condemn America’s use of military force in Vietnam.45 A more practical reason for opposing the war was its negative effect on Lyndon Johnson’s efforts to build a Great Society in the United States. Being disproportionately poor, black Americans stood to gain most from domestic liberal-reform policies like the war on poverty.46 However, the war in Vietnam helped to undermine the Great Society—both by diverting political attention from the domestic to the foreign sphere and by siphoning off billions of dollars in federal funding that might have otherwise have been spent on welfare programs.47 King referred to the war as “an enemy of the poor” in April 1967.48

Throughout 1965–1972, African Americans appear to have been more opposed than white Americans to the Vietnam War. Opinion polls repeatedly showed that blacks were the “most dovish” social group.49 In April 1967 the Chicago Defender surveyed black opinion regarding the war. The poll showed that 57.3 percent of blacks favored the United States pulling its troops out of Vietnam, always the least popular sentiment among opponents of the war.50 But black hostility to the war did not translate into active support for the peace movement. Despite widespread opposition to the war within the civil rights movement, and the peace movement’s consistent attempts to attract black support, the mostly white antiwar leadership was discussing the lack of black participation in 1972, just as it had been in 1965.51

Initially, the civil rights movement responded to the Vietnam War by stressing the discrepancies between America’s claims to be fighting for freedom in Southeast Asia while denying millions of blacks basic democratic rights at home. The legitimacy of the war itself was left unquestioned. African American leaders simply tried to use the conflict to increase the pressure on the federal government to meet the movement’s demands. For example, shortly before being taken to the hospital for treatment to injuries received on Bloody Sunday, 7 March 1965, during the Selma voting rights campaign, SNCC chairman John Lewis told reporters that he did not understand how President Johnson could send troops to Vietnam but not to Selma, Alabama.52 On 8 March the NAACP executive committee discussed the violence at Selma, and passed a resolution noting the irony that “the report of these carefully planned attacks on the Negro citizens” shared the “spotlight with the landing of U.S. Marines on Vietnam, sent to protect the Vietnamese against Communist aggression.”53 An editorial in the March edition of the Crisis declared that “the entire nation—the leader of the free world—has been compromised by the defiance of law, morality and humanity at Selma. American pleas for the ‘free and unfettered ballot’ in distant lands has been made an international mockery by Selma’s arrant flouting of basic democratic principles.”54

While attending the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) Washington Conference on 25 April 1965, John Lewis again attempted to use the war to advance the black cause. He told the delegates at the Metropolitan AME church that “if we can call for free elections in … Saigon, we can call for free elections in Greenwood and Jackson, Mississippi.”55 It would not be long, though, before the radical wing of the civil rights movement abandoned this uncritical approach to the Vietnam conflict and confronted the war head-on.