Читать книгу Northern Ireland’s ’68 - Simon Prince - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

Controversy is the lifeblood of history. If Burke taught us that truth has a certain economy of expression, John Stuart Mill taught us that truth also has a necessary vitality. In history, at least, ideas which are not challenged tend to atrophy and harden into dogmas. Modern Irish history in recent years has been marked by many serious and important debates, which tend to spill out of the academic forum to engage wider public interest. Was the 1798 rebellion inspired by the modernising ideas of the French Revolution, or was it essentially a sectarian jacquerie? Were the victims of the Great Irish Famine of 1845–9 sacrificed to a narrow vision of political economy, or did the British governments of the time do the best that could have been done under the circumstances? Who were the real victors of the Irish Land War – the Irish peasantry as a whole, or simply a privileged rural bourgeoisie? One event alone in the war of independence – the Kilmichael ambush – has produced a growing literature, involving significant numbers of locally based historians as well as professional academics, about whether Crown forces staged a ‘false surrender’ to lure Republican ambushers into the open and were rightly refused quarter thereafter, or whether this is a story to justify the deliberate killing of disarmed prisoners.

All these controversies, even the more tedious and embittered ones, are in principle to be welcomed. The willingness to question and debate is one of the most striking and attractive features of modern Irish historiography. There is one great exception to this rule – the historical treatment of the Civil Rights crisis of 1968. Here the iron hand of consensus rules. This is not without good reason. Northern Ireland in 1968 was characterised by a dead weight of Unionist–Nationalist antagonism which expressed itself in the denial of equal citizenship to the Catholic and Nationalist minority. The most striking example of this denial was the gerrymander of the province’s second city to ensure that the control of local government remained in the hands of the Unionist minority – but there were other significant injustices, not only in electoral arrangements but in the allocation of jobs and housing. In this sense, then, a moral case definitely existed in support of the civil rights movement.

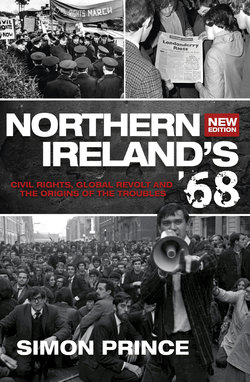

The strength of this moral case has, however, led to the suppression of all the more normal forms of historical enquiry. For example, what were the real motivations of the 68ers – in ’68, and not as reconstructed in later years? What was the relationship between the radical leadership of the movement and its support base on the street? What was its real international context? Here lies the importance of Simon Prince’s book. It applies all the techniques of historical questioning and research methodology one would expect from one of the most gifted young Cambridge historians (now teaching in Oxford) of his generation. Prince pushes aside the cobwebs and gives us a fresh look at one of the most important moments of modern Irish history. His book will provoke debate – and some disagreement – but it will shake up the subject and thus perform a great service.

Paul Bew Professor of Irish Politics Queen’s University, Belfast

May 2007