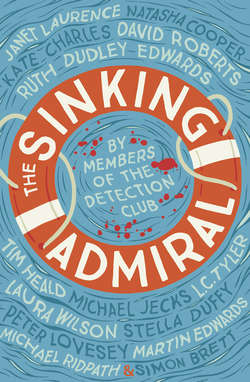

Читать книгу The Sinking Admiral - Simon Brett - Страница 10

CHAPTER FOUR

ОглавлениеAmy was surprised by the tears running down her cheeks. She knew it wasn’t just shock at discovering the body. It was an overwhelming sadness at the thought that she’d never hear the Admiral’s voice again. Maybe, somewhere deep down in her psyche, she had felt love for the old bastard.

She decided, rather than ringing the police from her cottage, she would have to go back to the pub and prepare herself for a long night of disruption and probably questioning.

Her basic knowledge of police procedure, gleaned from endless television cop shows, told her that she should touch as little as possible at a crime scene, but when she looked closer at the boat she saw something white, stuffed into the folds of the crumpled boat cover.

An envelope. Printed on it the words: ‘TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN’.

Sod not touching anything at a crime scene. No power could have stopped her from opening that envelope. Fortunately the flap was just tucked in, so she didn’t have to tear it.

She read what was written on the folded sheet inside.

I’m sorry. All the pressures were just getting too much. I’ve had my Last Hurrah and it’s better to go out on a high. Apologies to anyone who’s going to be upset by my death (though I don’t think there’ll be many).

Fitz

The text was not handwritten. It had been typed and printed. Possibly using the computer in the Admiral Byng’s downstairs office.

In other words, whoever had composed the suicide note, it certainly hadn’t been the computer-illiterate Fitz.

Which, to Amy’s mind was proof positive that the old boy had been murdered.

And made her absolutely determined to find out who had committed the crime.

A car in the blue and yellow livery of the Suffolk Constabulary was heading rapidly towards Crabwell.

‘Watch your speed, laddie,’ the DI in the passenger seat told his driver, Detective Constable Chesterton. ‘This isn’t life or death.’

‘It’s death, isn’t it?’ Chesterton said. ‘Death in my book, anyway.’

‘Come clever with me and you’ll find yourself back in uniform.’ DI Cole didn’t take lip from fast-track graduate detectives. ‘It’s only a suicide. There was a note beside the body, and it couldn’t be more plain.’

A suicide was difficult to envisage as anything other than a death as far as Keith Chesterton was concerned, but he knew better than to argue with ‘The Lump’, as Cole was known to everyone who worked with him. He cut their speed to fifty-nine and gave thought to the strange circumstances of the incident. They had collected the suicide note from the local bobby called to the scene overnight, who had told them the victim had been found on Crabwell beach lying in a dinghy partly filled with water and anchored in the shingle. A young woman out walking had made the grim discovery and then suffered a worse shock by recognising the corpse as that of her own employer, the owner of the pub that overlooked the beach.

‘So there’s no rush,’ Cole said. ‘It’s not like murder or a robbery, rounding up suspects. The perpetrator was the corpse, and he isn’t going anywhere.’

Only on the most momentous journey any of us will ever make, Chesterton mused. He had a spiritual side he kept to himself. ‘Where is the body right now?’

‘The mortuary, of course. They wouldn’t leave it in the open for all and sundry to gawp at. That wouldn’t be fitting.’

‘They could have put a forensic tent over it and taped off the area so nobody could get near.’

‘What would be the point of that?’ Cole said. ‘I keep telling you, there’s only one person involved in a suicide.’

‘But if it was suicide, how did he end up in the boat?’

‘You know what boat-owners are like. They have love affairs with the bloody things. When they die they can’t think of anywhere they’d rather be.’

‘Like a ship burial?’

‘I didn’t say anything about a burial, cloth-ears.’

‘So how do you suppose he managed to kill himself and end up there… sir?’

‘We’ll have to wait for the post-mortem, won’t we? My guess is that he had a supply of sleeping tablets and mixed them in with a bottle of grog from his pub, then swallowed the lot. Best way to go. He took the short walk to his dinghy, and crashed.’

‘Remembering to take the suicide note with him?’

‘Naturally.’

‘First tucking it carefully into the folded tarpaulin where it wouldn’t get wet?’

‘You’re making sense at last.’

‘And crashed. But we won’t know for sure until they test his body fluids?’

‘Right.’ Cole grinned to himself. ‘Have you ever attended a post-mortem?’

When Amy Walpole answered the insistent knocking and saw two strangers at the pub door she told them at once that she wasn’t open for business. There had been a bereavement.

‘We know about that, my poppet,’ the older of the two men said. He was grossly overweight, and dressed in a brown suit with a windowpane check that wasn’t just loud, it was bellowing. ‘It’s why we’re here.’

Amy wasn’t anyone’s poppet, least of all this clown’s. She decided they were journalists and slammed the door. Well, almost. The younger of the two placed the palm of his right hand against the wood before it closed. He was strong.

‘If you want trouble,’ Amy said through the narrow gap, ‘I’ll call the police.’

‘No need,’ the first man said. ‘It’s me and him.’ He held up an ID, and it didn’t look like a press-card. ‘Cole and Chesterton, detectives, here about the man found dead in the boat last evening. May we come in?’

The second man also dipped in his pocket with his free hand and produced his warrant card displaying his photo, and the insignia of the Suffolk Police. He was not bad looking, quite a dish, in fact, but Amy wasn’t in any mood to be friendly.

She opened the door fully and jerked her head to let them know they could enter.

‘Are you the barmaid?’ DI Cole asked.

She eyed him as if he were something the dog had coughed up. ‘Bar manager.’

‘The table by the window will do us nicely.’

‘For the time being,’ said DC Chesterton. ‘We’ll need to set up an Incident Room in here soon. Is there anywhere suitable?’

Cole’s look at his subordinate showed that he didn’t think an Incident Room would be necessary for such an obvious case of suicide, but Amy’s presence stopped him from voicing his objection. It wouldn’t do to let her know yet that he’d already decided what had happened. Perhaps they would have to go through the charade of setting up an Incident Room anyway.

‘Well, there’s the Bridge,’ Amy replied. ‘Fitz used it as an office. That’d probably be the best place for you.’

‘Thank you,’ said Chesterton politely.

Cole thought he had been silent for quite long enough. ‘You don’t have to offer us a drink, but a coffee wouldn’t come amiss.’

‘The machine isn’t on,’ Amy said. She could have boiled a kettle and given them instant, but she wasn’t feeling hospitable.

‘And isn’t that fried bacon I can smell?’

‘Breakfasts have to be booked.’

‘You could make an exception for Suffolk’s finest, couldn’t you?’

‘We cater for our guests, not casual callers.’

‘Ooh! That was below the belt,’ Cole said. They’d already seated themselves at the table. ‘Let’s see if we can soften your heart. Why don’t you join us, my love?’

‘Let’s get one thing clear,’ Amy said, remaining standing. ‘Call me Miss Walpole, if you wish. Anything else is offensive or patronising.’

‘Whatever you wish,’ he said. ‘We know a lady manager when we meet one.’

Amy took this as compliance, and drew up a chair.

‘Are we speaking to the same Miss Walpole who reported the incident on the beach last night?’

‘You are. After I found him I came up here directly and dialled 999.’

The younger of the two, DC Chesterton, had produced a notebook and was writing in it. ‘This was at what time, Miss Walpole?’ They were the first words he’d spoken, and he had a voice that went down warmly, like the breakfast Amy hadn’t provided.

‘Late, after midnight, towards one a.m. I’d closed the bar and was on my way back to my cottage.’

‘Hold on,’ Cole said, eager to regain control. ‘We’ll do this from the beginning. You were here in the pub all evening, I take it?’

‘Yes.’

‘Quiet, was it?’

‘Actually, no,’ Amy said. ‘The place was packed.’

‘On a perishing Monday night in March?’

‘We had the TV people in, making a documentary, and the locals got wind of it and wanted their five minutes of fame – well, five seconds more likely – so just about everyone was in, and some we never normally see.’

‘And was Mr Fitzsimmons present?’

‘No one calls him that,’ Amy said. ‘“Fitz” or “The Admiral”.’

‘Served in the Navy, did he?’

‘I can’t say for sure. He’d been to sea, that’s certain, and once owned a schooner. He was full of stories, but I got the impression they improved in the telling. He was at it last night for the TV, going on about lost treasure in the West Indies, or some such.’

‘So he didn’t appear unduly depressed?’

‘Quite the opposite. He was in his element, buying drinks and playing to the crowd. You had to admire him. He could work an audience like a professional, and he was making mischief, too.’

‘In what way?’

‘He talked about “treasure closer to home” and said they could look forward to all kinds of revelations the next day.’ She sighed. ‘That would have been today’

‘What did he mean by that?’

‘I’ve no idea. Earlier he’d been holding court upstairs in his private apartment that we call the Bridge, receiving a steady stream of visitors. He wanted to see me as well, but my turn was coming today.’

‘You don’t know what it was about?’

She shook her head. ‘I can only speculate, and you don’t want that.’

DC Chesterton said, ‘We don’t mind you speculating, Miss Walpole. You must have known him better than anyone else.’

She glanced across the table. Young Chesterton’s eyes were as remarkable as his voice, the colour of the sea off Crabwell on a bright May morning, and he didn’t seem aware of their power. She was willing to speculate for Chesterton. She wouldn’t need much urging to speculate about him. ‘I wondered if he’d decided to sell up. We’ve had falling sales all winter. Until this week.’

‘Familiar story, sadly,’ Chesterton said.

‘So he was depressed,’ Cole butted in.

‘Not at all,’ Amy said. ‘He obviously had plans for some new project. He was one of life’s survivors.’

Cole said with a leer. ‘“Was” is the operative word.’

Amy said, ‘I was asked for my opinion. You seem to have made up your mind he took his own life. I’m not so sure. I’ve known him three years.’

Now Cole blinked and straightened up. ‘Do you have any evidence that he didn’t kill himself?’

‘Quite a bit,’ Amy said. ‘Earlier in the evening I went for a breath of fresh air along the beach. I’d been run off my feet until then, but it had gone quiet in the pub because the TV people were on a three-hour break. I happened to meet the Admiral. He was beside his boat, checking the cover, I think.’

‘Really? And did you speak?’

‘Of course. I enquired what he was doing and he said there had been too many thefts from boats. I remarked that he’d been extra busy with the visitors to the Bridge all day, and I asked if he’d spoken to Ben Milne, the TV man. He said ironically that he was reserving that pleasure for tomorrow.’

‘Ironically?’

‘He called Mr Milne a cocky young man, and he was right. Then he added that he wanted a long talk with me, but it would have to wait till the next day because he planned to get extremely drunk.’

Cole held up a finger. ‘Got you. You’re thinking he drank himself to death.’

‘Not at all. I’ve seen him drunk before and he was always fine the next day. My point is that he had definite plans for today. He wasn’t suicidal.’

‘The facts prove otherwise,’ Cole said. ‘There was a suicide note in the boat.’

‘I know,’ Amy said calmly. ‘I found it and showed it to the policeman who answered the 999 call.’

‘So?’

‘So I don’t believe the Admiral wrote it.’

‘Oh, come on,’ Cole said. ‘It’s the clincher. What are you going to tell me now – that he was illiterate?’

‘Couldn’t use a computer,’ Amy said. ‘The envelope was printed – “TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN” – and Fitz hadn’t the faintest idea how to work the printer. Have you seen the note?’

‘It’s in an evidence bag in the car. We picked it up this morning,’ Chesterton said. ‘Both the note and the envelope were computer-generated.’

For that, he got a glare from his superior.

‘It’s no big deal,’ Cole said. ‘Any fool can learn how to use a computer.’

‘And print off a page – and an envelope as well?’ Amy said. ‘The Admiral was no fool, but he wasn’t capable of that.’

‘The wording couldn’t be more clear,’ Cole insisted, and did a rapid recap. ‘All the pressures getting too much, he’d had his “Last Hurrah” and was going out on a high, with apologies to anyone upset by his death. No arguing with that.’

‘If he actually wrote it,’ Amy said. ‘If he didn’t, your so-called clincher is a busted flush.’

‘We’ll see about that, Miss Walpole. We need to speak to the people who were called up to the Bridge. Did any of them tell you what the Admiral wanted?’

‘Not one. They were remarkably tight-lipped, almost as if he’d asked them to keep a secret.’

‘We’ll winkle out the truth, don’t you worry. That’s our job. I’d like you to make a list of those concerned.’

‘I didn’t see them all. I was busy serving while it was going on.’

‘Jot down any you remember.’ His eyes slid upwards. ‘What was that?’

A sound had come from upstairs.

‘A guest, I expect. We do let rooms, you know.’

Ben Milne appeared at the top of the stairs. ‘How’s my breakfast coming along?’

Amy called back, ‘I’ll tell Meriel. Is it the full works, Ben?’

‘With a large mug of black coffee.’

‘No problem.’ She turned back to the policemen. ‘That’s the TV guy, Ben Milne. Excuse me a moment.’ And she was off to the kitchen.

Cole looked at Chesterton and muttered, ‘No problem, my arse. What about “the full works” for you and me, then?’

Ben had come downstairs and walked straight to their table. ‘Have we met? I don’t think so. Ben Milne. Are you from the village?’

‘Police,’ Cole said, ‘enquiring into the death of the landlord.’

‘Dire, yes. Woke me up, all the comings and goings in the small hours. Why did he do that, do you suppose?’

‘That’s what we’re in process of finding out, sir. You’re making a TV show, I understand.’

Ben winced as if he’d been stung. ‘A “show” it is not. This is for real. Documentary filming. We point the cameras and go with the flow. You never know what you’ll get. So far, it’s been better than I could have hoped, and now we’ve struck gold with the Admiral dying.’

‘Struck gold?’ Even Cole’s jaw dropped.

‘Put yourself in my position, filming a failing business just at the moment the head honcho tops himself. A tragedy played out as we watch. I just wish my dozy cameraman had been here last night to shoot the beach scene. We might do a mock-up, now I think about it. The boat’s still there, isn’t it?’

Chesterton nodded. ‘But if this is a reality programme—’

Ben was too hyped up to listen. ‘The networks will break their balls to buy this. I see world-wide sales. It’s got Emmy written all over it.’

‘Who’s Emmy?’ Cole asked.

Chesterton saved him from embarrassment by saying, ‘There may be legal complications.’

‘How come?’ Ben asked, frowning.

‘If – for the sake of argument – a court case ensued from this, they could stop you from airing the programme.’

‘What are you on about – a court case?’

‘You could prejudice the legal process.’

‘Bugger that,’ Ben said. ‘I’m on a roll. I’m not stopping for anything. Are you going to question the witnesses? I need it all on film.’

And now Cole waded in. ‘You can get stuffed. You’re not filming us.’

‘However,’ Chesterton added in an inspired moment, ‘we need a copy of every frame you’ve shot up to now. It could be crucial evidence.’

‘No way,’ Milne said.

‘No? Obstructing the police is an offence under section 66 of the Police Act, punishable with six months’ imprisonment. We need that film by noon tomorrow.’

Cole eyed his assistant with surprise. There was more to the young man than he’d supposed.

Ben looked at his watch. ‘You’ve buggered my schedule.’

Amy returned with a tray bearing Ben’s breakfast: a large mug of coffee, orange juice, toast, marmalade, and a plate stacked high with bacon, egg, sausages, mushrooms, tomatoes fried bread.

‘I don’t have time for this,’ the TV man said. ‘I’ve just been given a whole new heap of work.’

For a moment Amy stood holding the tray, at a loss.

But Cole said, ‘Leave it with us, Miss Walpole. It mustn’t go to waste. Are you off the coffee as well, Mr Milne?’

Feeling better after their fortuitous breakfast, the two detectives went upstairs to look at the Bridge, the function room adjacent to the owner’s living quarters. Presumably all the private consultations had taken place here the previous day. Dusty pictures of sailing ships crowded the walls. A dusty glass cabinet was filled with a collection of razor shells, conches, scallops, and clams. Lines of small dusty flags were suspended from the ceiling like Christmas decorations. At the far end, a huge desk that could have doubled as a poop deck was filled with as many bottles as the bar downstairs, but most were empty. There were some unwashed glasses as well. Beneath them, acting as coasters, were numerous sealed letters, some heavily stained.

‘From his energy supplier,’ Chesterton said, picking several up and leafing through them. ‘Gas, the bank, a brewery. Most of these look like unopened bills.’

Cole was sitting behind the desk in the Admiral’s padded armchair under a ship’s figurehead of a topless blonde woman. ‘It just confirms the obvious. He’d given up. He was desperate.’

‘There’s no computer up here, and no printer. There isn’t even a filing system.’

‘An old-fashioned phone,’ Cole said, lifting an upturned waste-paper basket to show what was underneath. He opened the desk drawer and saw that it contained one item: a corkscrew. ‘Even his bottle-opener is out of the ark.’

‘Makes you wonder if Miss Walpole had a point about him being technophobic,’ Chesterton said.

‘Techno what?’

‘Unable to use a computer.’

‘We’ve only got her word for that,’ Cole said with irritation. ‘She told us herself his stories grew in the telling. The man was living a lie, pretending he’d spent his whole life at sea. Bloody fantasist, if you ask me. All this seaside tat around us – the stuffed swordfish and the old lamps and the ships in bottles – is just props. Anyone can pick them up in local junkshops and furnish a pub with them. In reality, I reckon he was a failed businessman or a bloody civil servant, perfectly capable of printing that suicide note. You may be sure there’s a computer somewhere in this pub.’

‘I spotted one downstairs, in the little office behind the bar,’ Chesterton said. ‘They’d need it to bill the overnight guests.’

‘There you are, then.’

‘But I was impressed by Miss Walpole. She’s worked with the guy for three years, and she doesn’t buy the suicide theory.’

‘It’s more than a theory, sunshine,’ Cole said. ‘It’s what happened. And you’d better stop being impressed with that bimbo. I saw the way she was batting her eyelashes at you. She’s the sort who picks up DCs and drops them from a great height. I’ll show you how to deal with a woman like that. Watch me when we go downstairs.’

‘Should we look at his living quarters first?’

‘If you like, but I don’t expect to find much.’

Up a small flight of stairs they found a sitting room filled with more maritime objects (or seaside tat), as well as a sofa and armchairs. A bookcase was lined with dog-eared paperbacks by C .S. Forester and Patrick O’Brian. Beyond that was the bedroom and a small en suite.

‘Take a look in the medicine cabinet,’ Cole said.

‘What am I looking for?’

‘Dangerous drugs, barbiturates, sleeping tablets, anything he could overdose on.’

After a few minutes of searching, Chesterton said. ‘Nothing at all like that.’

‘Proves my point,’ Cole said at once.

‘How?’

‘Obvious. He must have swallowed the bleeding lot.’

They returned downstairs to the bar, where the sole occupant was a woman at breakfast wearing a white bathrobe and slippers and with her hair in a plastic shower cap. She stared at them in horror. ‘Oh my God, don’t look at me. I’m undressed, not made up, not for viewing. I thought it was safe to eat my scrambled egg while my hair was drying. Go away, whoever you are.’

‘It’s a public bar, ma’am,’ Cole informed her.

‘Residents only at this hour.’

‘Do you live here, then?’

‘A paying guest. Go away. Vamoose. Shoo.’

‘We’re on an investigation.’

‘You’re not the…?’

‘We are, following up the tragic event of last night.’

‘Oh my God! Then if you won’t leave, I will. Don’t you dare try and stop me.’

With that, she got up, dashed across the room and upstairs, leaving a slipper on the lowest step.

‘There’s your chance, Prince Charming,’ Cole said with an evil grin. ‘Why don’t you go up and see if it fits?’

Chesterton rolled his eyes and said nothing.

In a moment Amy Walpole returned. ‘Didn’t Ianthe finish her breakfast either? You two won’t be popular with Meriel, our cook.’

‘Is that who she was – Ianthe?’ Cole asked. ‘Ianthe who?’

‘Berkeley. Another guest. Publishing person.’

‘Were she and the TV man sharing a room?’

She frowned. ‘Not unless…’ Then she reddened. ‘Is that what she told you?’

Cole shook his head. ‘Deduction. First the man appears from upstairs, looking like the cat who found the cream, then the woman in a state of disarray.’

‘That’s observation, not deduction, and they had very good reasons for looking like that, unconnected with each other. Anyway, all the guest rooms are on the same landing.’

‘I’m broad-minded,’ Cole said. ‘The only thing that interests me is that they were both here yesterday, when the Admiral was still alive. We’ll need to question them about his state of mind.’

‘I keep telling you he was in excellent spirits.’

‘Yes, eighteen-year-old malt. There are some empties on his desk. Did he take anything to help him sleep?’

‘He never mentioned it.’

‘It makes a deadly mix, alcohol and sleeping tablets.’

‘He wouldn’t do that.’

‘There’s no denying he ended up dead, Miss Walpole. We weren’t informed that he shot himself, and I doubt if he drowned in a few inches of water.’

‘He might have, if he was already unconscious.’

‘True.’

‘Is concussion a possibility?’

‘A knock on the head, you mean? Self-inflicted? No chance.’

‘I didn’t say self-inflicted.’

Cole grinned. ‘You watch too much crime on television. It isn’t like that in the real world. Don’t forget we’ve got the suicide note.’

‘The questionable suicide note,’ Amy said.

‘All right. Let’s play it your way. The only people who know about the existence of this note are your good self and the officer who attended the scene last night. Have you mentioned it to anyone else?’

She hesitated for a nanosecond. She had mentioned it to Ben. But she didn’t want to complicate things, so she said, ‘No.’

‘Then don’t. This is how we root out guilty parties. If someone else concocted the note, as you seem to be implying, they’ll give themselves away at some stage. Clever, eh?’

‘I hadn’t thought of that.’

‘And just to be quite certain, we’ll be fingerprinting the paper the note was written on. Forensics can get prints off anything these days.’

Amy caught her breath. ‘Mine could be on it. I lifted the envelope from the tarpaulin.’

‘But they won’t be on the letter inside. The only prints we can expect to find are those of the person who wrote it and the officer who opened it. If, God forbid, we find any others, that individual will have some explaining to do.’

Amy was silent.

‘So this will be our little secret, Miss Walpole. Are you with me?’

She gave a nod, but her mind was in turmoil. Touch as little as possible at a crime scene. If only she’d listened to her own inner voice.

‘Another thing,’ Cole said. ‘I want you to print something now on your computer. We noticed you’ve got one in your office.’

‘Print what?’

‘A notice in large letters saying the pub is closed until further notice owing to the sad death of the owner.’

Having printed the note as requested, and closed the door on the detectives, noting incidentally that the younger of the two looked as good from the back as he did from the front – then scolding herself for even thinking that when she’d seen Fitz dead not twelve hours ago – Amy let Meriel know that she might as well have the day off.

‘With the pub closed until the police decide otherwise, there’s nothing else we can do.’

Meriel was not happy, and, looking around the kitchen, half a dozen dishes seemingly on the go at once, a massive number of vegetables already prepped, Amy could see why.

‘You don’t usually work this hard on a Tuesday, Meriel.’

‘We don’t usually have a film crew in the bar dragging in all and sundry, and hungry with it. We don’t usually have detectives eating my full English. And I don’t usually have the chance to… to… oh never mind. Get out of my way and I’ll try to salvage some of this. They’re going have to let us open once they confirm it’s suicide.’

Amy turned in the door. ‘How do you know about that?’

Meriel smiled. ‘Little pitchers, big ears. And that,’ she pointed to the extractor above the big catering oven, ‘still leads into the old chimneys, they’re all connected. When it’s turned off, I can hear half the conversations in the bar, clear as day. Now if you don’t mind, you may not have anything to do with the bar closed, but I have no intention of letting this lot go to waste. It’ll do for funeral-baked meats, if nothing else.’

Amy used the locked front door as an opportunity to give the bar a good clean. The old chairs, the scuffed walls, the tables with their ingrained sticky beer would also be put to use for the wake, she was sure of that, it wasn’t as if there was anywhere else to go after the funeral – once they were allowed to have the funeral – she might as well make the bar as presentable as possible. She shook her head, feeling tears coming on again, smarting at the back of her eyes. No, she would not cry. Last night was bad enough, she wasn’t going to let it all get to her in broad daylight as well. A deep breath, a bucket of hot water, and a brutally effective and pungent spray cleaner, that was more use than tears right now.

As Amy got to work she thought how odd death was, the way someone, anyone – loved or hated, it didn’t matter – just suddenly stopped. The incredible cessation of life. No wonder people had invented religion to make sense of it, nothing else did. She scrubbed harder, as old memories, unbidden, threatened to well up. She’d trained herself to be tougher than this, not to look back, not to dwell. It wasn’t even as if Fitz had been a good boss, his business skills were appalling, but he had been kind to her when she’d needed help, and she’d not forget that. The arrival of not one, but two, good-looking men in town was not going to let her forget Fitz’s kindness, even if most people had been all too ready to consider him a bit of a joke. There had been much more to Fitz than most people saw, Amy wasn’t even sure she knew what that more might be, but she knew he wasn’t just the village drunkard, the old buffoon. And he was no suicide. Whatever he’d been planning for his ‘Last Hurrah’, it had been something he’d personally found thrilling, something that had generated that twinkle in his eye. She threw away the second dirty bucket of water and rinsed the sink. Fitz had been planning something all right, but it most certainly was not suicide.

Amy was halfway back to her cottage, the wind no less brutal than it had been in the middle of the night, the sky only slightly less lowering, when a new thought occurred to her. Ben Milne and his cameraman Stan had been filming most of yesterday afternoon. Cutaways of the pub, close-ups of the dust caught in the nautical ceiling decoration – ‘for atmosphere only, love’, Stan had assured her, with a wink to Ben – long shots of the desolate seascape beyond the small windows, and plenty of vox pops, where Ben – as producer-presenter – had his own style, simultaneously enthused but also laid-back, just this side of too cocky, yet not quite as charming as he no doubt thought himself. They must have taken at least a couple of hours of video footage, and not all of it could have been her own or Meriel’s cleavage, despite Stan’s obvious interest in the female form. She’d been too busy with the influx of non-regulars, all of them keenly hoping to get caught on camera, to pay much attention to the people who’d visited Fitz yesterday afternoon, but Amy was aware that the stairs up to the Bridge had been busier than usual. And somewhere in all that footage there might well be a clue to what else had been planned yesterday, something that would make the police look more closely into their suicide theory, something that would help her help them – even if they clearly did not want her help.

Amy turned on her heel and headed back to the pub. The last she’d seen of him, Ben was stomping upstairs to his room, with dire threats about suing the pub if the promised Wi-Fi didn’t work, and how the hell was he supposed to copy all their film in the time the police had given him. Amy knew enough about technology to know he needed neither Wi-Fi nor a great deal of time to copy from the camera memory card to his own laptop’s hard disc or a memory stick, but she’d assumed he was using the tantrum to get himself off and back into bed, making up for lost sleep and last night’s hangover.

She let herself back into the pub and checked in the kitchen. She was pleased to see Meriel appeared to have tidied everything well enough, and then went upstairs to Ben’s door. She knocked, and was surprised when Ben opened up almost immediately.

‘About bloody time,’ he said, walking away, neither looking at her, nor removing his headphones, ‘just put it on the bed, I asked for that over an hour ago.’

‘Asked for what?’ Amy said, standing in the doorway.

‘Huh?’ Ben turned and was clearly surprised to see Amy. His frown burrowed even further into his forehead for a moment, until he remembered he was frowning at Amy, and he fancied her, or he would do if she’d shown any sign of fancying him back, as most women did. He tried – too late – to offer his lopsided grin, the one his viewers seemed to find so attractive.

‘Who were you expecting?’ Amy asked.

‘That woman, in the kitchen, the one who thinks she’s the next voluptuous telly cook.’

‘Meriel,’ Amy prompted

‘Merry hell, yes.’ Ben chuckled, pleased with his own joke, no doubt planning something similar for the documentary voiceover. ‘I went down over an hour ago, you were scrubbing hell out of that old table in the corner, I asked her if I could have a sandwich and a cup of coffee. If I have to waste good filming time copying stuff for the police, I might as well have some food after all. She said she’d bring me something up.’

‘She must have forgotten.’

‘I thought she wanted to get a series out of me?’

‘Maybe she’s realised you don’t do “shows”,’ Amy said with a grin, copying Ben’s earlier tone to the policemen.

‘Yeah, or maybe she’s gone off to kill a fatted calf and present it to me, apple in mouth and fat glistening.’

‘When I last saw her she was putting the stuff she’d been prepping into the freezer. The police have insisted the pub’s closed for business.’

‘They’re not about to turn me out of my room, are they?’

‘No. Actually, another thought… Fish market.’

‘What?’

‘Tuesday. Fish market, well, more of an old transit van, comes all along the coastal villages, Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, around about this time of day. That’s where Meriel’ll probably be.’

‘Whole poached sea bass I’ll be getting then?’

‘More than likely.’

They both smiled, and then Amy was suddenly aware that she was standing in Ben’s bedroom, the unmade bed astonishingly inviting, no doubt due to her lack of sleep, not at all to the lopsided grin Ben was trying out on her again.

‘I was wondering…’ she said.

‘Yes?’

The grin again; Amy wondered if his cheek ever ached. ‘The police are pretty sure Fitz committed suicide.’

‘The note’s a bit of a clue there.’

No grin this time, and Amy ignored him. ‘But I doubt Fitz even knew where the envelopes where in the office, let alone how to type and print a note as well as an envelope. He is – he was – a complete technophobe. Actually, worse than that, not phobic, he honestly didn’t care, one way or the other, he wasn’t interested in learning. I don’t believe he wrote that note.’

‘Then…’

‘Then someone else did. And that someone else may well have visited Fitz yesterday afternoon, the place was heaving, I have no idea who went up and down those steps to the Bridge. But what I do know is that Fitz was very much himself, and truly excited about what he had planned for his “Last Hurrah” as he called it. Something happened between him and one of his visitors – maybe more than one of them, I don’t know – but something must have happened. Either something that did make him kill himself – even though I can’t see him doing that, or…?’

‘Or indeed. And you think some of my footage might show who went up to see the old man?’

‘I do.’

Try as he might, Ben just couldn’t stop his dark eyes lighting up. Amy watched him as he worked it all out, in the sharpest televisual terms, she was sure – a derelict old pub, a ‘character’ of a publican, a potential suicide that segued neatly into murder. She couldn’t really blame him, he’d come all this way hoping to make a perfectly ordinary little programme that gently mocked local characters and made people up and down the country feel better about their own stolid lives from the safety of their own soft sofas, and now he’d been handed a real life actual drama. No wonder his dark eyes gleamed. To his credit, he didn’t leap up and punch his fist in the air – not that the low beams of the room would have allowed it – he simply nodded.

‘Good point. We can have a look if you like – as soon as I’ve given the copy of the footage to the police. And maybe we could have a coffee and a bite to eat while we do it?’ He looked around the bedroom, perhaps thinking of it as a suitable venue for their investigation, but something he saw in Amy’s eye prevented him from making the suggestion. ‘I’ll bring the laptop down to the bar and get set up, while you go and see what treats the lovely Meriel might have left in the fridge.’

Amy went back down to the kitchen, while Ben quickly gathered together his gear. At least her suggestion had wiped the lopsided grin off his face.