Читать книгу Frankel - Simon Cooper - Страница 7

Prologue

ОглавлениеIn horse racing, greatness is defined by speed. Being the second fastest counts for little. You have to win. And win. And keep on winning until every challenger of your generation is put to the sword. Such a thing so rarely happens that most people pass through life without the privilege of seeing such an animal. Occasionally a contender will arrive, burning up the turf until the dream of greatness is shattered in defeat; that precious cloak of invincibility torn to shreds by another.

On a rainy Suffolk evening, did our locally trained bay colt have any idea that he was about to embark on that path to the ultimate in racing greatness? To become the one against which all horses of the past, present and future would be judged and likely fall short. Let’s face it, he probably didn’t.

In truth, despite the remote possibility of such a thing, he had a whisper of a chance; he was bred if not to be great then at least to be fast. But that counts for only so much. Hundreds of thoroughbred racehorses debut each season with bloodlines as good as our horse. But breeding will only take you so far; the rest lies deep within, far beyond human intervention.

If you’d been a casual observer among the thousands gathered at Newmarket races on 13 August 2010, the third race of the night didn’t promise very much. In fact, it was a meeting far removed from the highest rank, designed more to draw a big holiday crowd than for quality racing. It was one of those humdrum, unregarded workaday fixtures which are the bread and butter of horse racing around the globe – excepting one horse.

You probably didn’t bother to go to the paddock after the second race to watch the horses parade for the next; few did. What was meant to be a balmy summer evening had turned cold with squally-soon-to-become-heavy rain. Trainers, jockeys, stable hands and officials were all scurrying around truncating the preliminaries to the shortest possible duration. The lawns in front of the stands were pretty well deserted; the crowds were jammed inside. A few hardy types sheltered under umbrellas to be close to the horses, but in truth they were few and far between. After all, this was just a minor race with a dozen horses, eight of which had never raced before and the remaining four had hardly set the world alight, without a win between them.

For our horse, this was to be his racecourse debut; he was one of that eight. But was he the special one? Maybe. There was a buzz about him. He’d lit up the training gallops. Been the gossip of this racing town. He’d been named in honour of one of the greatest trainers of modern times. Expectations were high. A sick man, his trainer, was being rejuvenated just by his very being. But this was a wretched night; his stable hand had even lost his shoe in the quagmire leading up to the start. If it all went wrong, there were at least excuses to hand.

By the time you’d extracted yourself from the bar, placed a bet and found a vantage point in the stands, the horses would have been long gone, gathered at the start a mile away. Without high-powered binoculars they would have been nothing more than a wet smudge on the otherwise empty horizon of Newmarket Heath that doubles as a racecourse. With binoculars you’d have seen jockeys hating the rain, crouched over their horses, keeping them calm with a circling routine. Had you been at the start, you would have heard the starter’s assistant complete the roll call as the handlers stepped forward to lead each horse in turn into the designated compartment of the starting stalls. A moment later, the loading complete, the gates of the stalls would spring open. The race was on.

Did our horse lead from pillar to post, leaving all others struggling in his wake, the rain-sodden crowd gasping in awe at his performance? I’d like to tell you yes, but it wasn’t really that way. In a race that lasts less than two minutes – this was just a mile – a quick getaway helps. But our young blood blew it. Months of training counted for nothing as this critical moment vanished in a trice. He was closer to last than first with half the race run. Had you placed a bet on him – he was the favourite, after all – you might have had reason to worry. But really you need not have done. Our horse was a cut above the rest. He knew it. And you, too, would know it soon.

He had been trained to run this way. He was headstrong. A horse who knew his mind but was prone to run too fast, too soon. His trainer, the best of the best, saw this in him so taught him the value of patience. The waiting game. Cruising behind the others until the moment was right. And that is how this race has become a part of horse-racing history.

In the wet gloom, as the track rose towards the finishing line, the jockey eased our horse out from behind the pack to make his run. There was nothing hurried. Really, there was nothing to doubt. He drew level with the leaders, kept time with them for a few strides as if to make some point before pulling away with ease as the winning post flashed by. Whether you were a seasoned racing professional or a once-a-year punter, our horse would have caught the eye. ‘Impressive’, you’d have said. ‘Very impressive.’ And you’d have logged the name of our horse in that part of your brain reserved for something out of the ordinary.

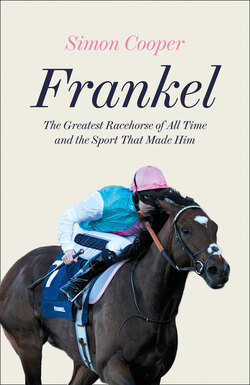

One hundred and three seconds on from the start, the horse drawn in stall ten had passed the winning post ahead of the rest. That was to become something of a habit as Frankel was now, despite the apparent inauspiciousness of the occasion, on his way to becoming the greatest racehorse to ever live.