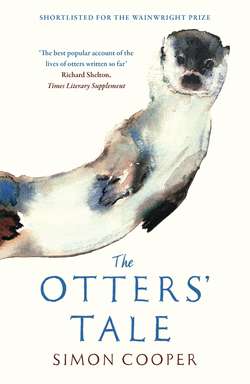

Читать книгу The Otters’ Tale - Simon Cooper - Страница 9

CHAPTER 1 ALONE AND AFRAID Two years earlier

ОглавлениеAs dusk started to fall, Kuschta gradually uncoiled her body, stretching away the stiffness of a day spent asleep. Sniffing the air, she could tell the holt was empty without even opening her eyes. There was nothing unusual in that, but she was comforted by the slight warmth radiating from the indentation left by her mother in the soft bed of the rotten willow trunk which they shared. She was clearly not long gone. Kuschta weighed up her options. She guessed her mother would not be far, probably down at the weir pool diving for eels – easy pickings, as they gathered in great numbers before their summer migration to the sea.

In truth, Kuschta had options, but only of the no-win kind. On that fateful evening the outcome was to be the same, whatever her decision. Whether she stayed in the holt or went in search of her mother she was destined to greet the following dawn alone. But knowing none of that, Kuschta assumed her mother would return as she had done every day of her fourteen-month life. Maybe with a tasty eel that they would share? So oblivious to the future, Kuschta chose to stay put, recoiled herself, buried her nose in the crook of her hind leg, closed her eyes and was instantly asleep.

You could walk close by the spot where Kuschta slept and not give it a second glance. In fact, I’d hazard that even if you stopped and stared you might not be much the wiser. Otters are not like badgers, which dig elaborate setts, creating multiple cave-like entrances with the spoil of their digging spread around for all to see. In their choice of home otters are pragmatists, moving between ‘holts’, which are usually tunnels amidst the roots of trees beside the river, and ‘couches’, well-concealed resting places above ground. Neither is particularly easy to spot because they are so much a part of the landscape, used by generation after generation of otters. Twenty, thirty, forty years of continuous use is not uncommon – even a century has been recorded. This we know from otter hunts that combed every inch of bank until they were banned in the 1970s. A diligent huntsman would know every hover, as some called them, returning time and again to seek out their prey and record the locations for future hunts.

Otters are not builders like, say, beavers; they take what they find and adapt it. The best holts are created by Mother Nature. An ash or a sycamore grows tall beside the river until gravity takes a hold as the water erodes the bank beneath, so the tree starts to lean out over the river. These trees are well adapted to such a pose, the wide shallow roots providing enough support for some considerable elevations of lean. But it is in that process of tipping that the den is made; the movement lifts the bank to create a cavity under the roots, which in turn becomes the canopy of the holt. And in the otters go. Some judicious digging will create a labyrinth of dry tunnels and, if all goes according to plan, there may even be an underwater connection to the river.

Couches, on the other hand, are rather more at the making of otters, but they are, as the name suggests, the more informal of the two habitats. A pile of reeds, dry moss or leaves in a thicket of brambles a few yards from the river would be typical. It’s more of a good weather than a bad weather sort of place, though not always. In wet flood plains where dry holts are scarce, elaborate couches are created as alternative homes, but more generally the couch is the resting place where otters feel safe to sleep, catch the sun and play whilst whiling away the daylight hours, hidden from view.

I guess Kuschta would care little for my subtle differentiation between couches and holts. All she knew was that the hollowed-out crack in the willow branch had long been a favoured resting place for the family; warm, inviting and familiar. The willows that thrived by the river had this strange way of growing that helped the otters; shooting up fast, they soon outgrow themselves so much that the limbs burst or crack open lengthways before snapping away from the trunk and falling to the ground. Laid out, the cracked branches look a little like an open pea pod, and at first there would probably only be just enough room for an otter to squeeze inside the fissure in the wood. But in time the timber would start to rot from the inside out, the constant comings and goings of the otters gradually hollowing out the trunk. The bark and cortex, still connected to the mother tree, stay alive even to the extent that the bright green shoots continue to grow up to create a sort of curtain in front of the hollow. It is as natural a hiding place as you’d ever find.

It was well into the night when Kuschta woke up with a start; something or someone was passing by. She had no reason to be scared, but she was, freezing rigid until the sound faded into the distance before she raised her head to check the hollow. Empty. She pawed at the soft, rotten wood where her mother usually sat. Cold. Cold as if she had never been there. Something wasn’t right. Wishing it wasn’t so, Kuschta stared out at the river for a little while, the landscape bathed in the silver light of a half moon, until she reached a decision – she’d go to find her mother.

Parting the willow-whip curtain, Kuschta pushed herself out of the hollow and slid into the water. In her mind there was no doubt she would find her mother at the weir pool. It was one of their favourite haunts. As she swam she became more confident in her decision. Familiar landmarks marked the route. The moon lit the way. The weir was not far. Turning the last bend with it just ahead, Kuschta slowed her pace. She half expected to see the silhouette of her mother on the wooden beam that braced the right-hand side of the structure. The two of them often sat there to share the spoils, but tonight it was empty. No matter. Kuschta stopped paddling, letting the current take her along whilst straining her ears for familiar sounds above the regular pounding of the water as it crashed over the weir. Nothing.

Scrambling up, she took in the whole pool from the vantage point of the beam with one swift movement of her head. The fast plumes of water that washed to the centre of the pool then gathered together to push out and on through the mouth to continue on as one river. The gentle slope of the grassy bank that led down to the water on the far side. The line of alders on the nearside, all gaunt and black against the night sky. All utterly familiar but totally absent of the one thing she sought. Confused and deflated, Kuschta settled down on the beam to wait for her mother to return. Time was her only hope.

It is probably better that at this point Kuschta doesn’t know what we know, namely that she has been deserted by her mother forever. Deserted is a harsh word, but from such swift and brutal decisions, good will come. It’s just that sometimes it doesn’t seem that way at the time.

Otters are relatively unusual in the mammal kingdom of Britain, breaking with the norms of reproduction. In the standard way of things, offspring are born in spring, raised in the summer and go their own way by the autumn at the latest. But for otters it is somewhat different, the reproductive cycle being closer to biennial than annual, with the pups, the females in particular, staying with the mother until they are well over a year old. With so much time together, the bond between mother and pups is intense; the father is rarely a factor, moving on soon after mating. Otter pups are truly dependent on the mother; they can’t swim or hunt without being taught. But even when armed with those basics they can’t go it alone. Three months, six months, nine months, a year – they will starve without maternal oversight all the way into young adulthood.

The family group is everything in the upbringing of an otter. The litter, anywhere from one to four pups, will spend every waking and sleeping hour together with the mother until they go their separate ways. The first schism comes earlier for male pups. Approaching one year of age, he will be as big as his mother, and with increasingly unruly behaviour and becoming more dominant than she would like, the mother takes a stand against her son and drives him away. Shorn of her guidance and protection, this adolescent faces an uncertain future. Travelling alone, he has to fight for his life both in terms of finding a territory to call his own and food to live on. Mature males will care little for his intrusion and other mothers will be fiercely protective of their patch. He will find it hard to rest; the itinerant life will drain his strength as he is constantly moved on. His hunting skills are still evolving; surviving day to day in unfamiliar places is a constant battle. There are plenty for whom the battle is too much, dying of exhaustion and starvation. His sisters will eventually reach a similar fork in their lives.

Survival, and the search for food to ensure survival, can also determine otters’ habitat. Sometimes the choice of a coastal home is made of necessity, driven along to the mouth of a river in a search either for territory or for food. Otters are very ‘linear’ in their habits and outlook; they rarely stray far from water, preferring to travel great distances along watercourses rather than heading inland. The only common exception to this is the birthing holt, which, for reasons we will discover, is located well away from the water. So when an otter can’t find a territory to call his or her own, or possibly when there is not enough food, he keeps on travelling until, as with any river, he reaches the sea. Saltwater, freshwater – it is all the same to an otter. Coastlines offer the same opportunities for raising a family. Let’s face it, if your kind has been able to span so many continents and landmasses, you are going to be pretty adaptable.

It is, however, worth making a distinction here between sea otters and otters that live by the sea. Kuschta – and every single otter that has ever existed in the British Isles – is of the family Lutra lutra, more commonly referred to as the Eurasian or European otter, which is one of thirteen different known otter species around the globe. As the name suggests, the European otter is indigenous to Europe, but also to Asia and North Africa, with a truly phenomenal spread across the northern hemisphere. West to east, with a few exceptions, such as the Mediterranean islands, this species walks every landmass from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. From northern Russia to the Indian Ocean, snowy Finland, dusty Morocco, the foothills of the Himalayas, humid Thailand or the frozen shores of the Bering Sea – if you know where to look, you’ll find Lutra lutra in all these lands.

On the other hand, sea otters – Enhydra lutris – are an entirely different species altogether, found along the shallow coastal waters of Russia, California and Alaska in the northern Pacific Ocean. They rarely venture onto land, living entirely in the water, and are famous for floating belly up in the kelp forest that hugs the shoreline. Conversely, British otters that live by the sea are just your normal inland otters that have picked a different type of home. In the Scottish islands, where they thrive, this way of life is the practical alternative, where there is more productive coastline than freshwater river or loch.

As the sky started to show fire red behind the grey clouds in the pre-dawn, Kuschta knew it was time to move. She had seen and heard nothing during her night-time vigil. Neither friend nor foe had broken the silence or the surface of the eel pool. Stretching her stiff body on the beam, she knew she should have used the darkness to hunt, but with the sun coming up fast it was now too late. Darkness is the friend of otters; they navigate their world in the secret time between dusk and dawn. Daylight is the time for rest, night the time for travel, food and adventure; this much Kuschta had learnt from her mother. Impelled by the rising sun, Kuschta needed to make it back to safety or at least somewhere familiar. Sliding into the water, she swam quickly upstream, sending out unruly waves that rocked at the reeds on either bank, first startling a moorhen who let out an anguished squawk of protest, and then a water vole who simply paused his weaving amongst the stems until the commotion was past. Silhouetted against her skyline, the cattle grazed in the meadows, their scrunching remarkably noisy, even to her ears. A fox trotted across a bridge, no doubt heading, just as she was, to a daytime lair. The dawn chorus was reaching fever pitch as the birds laid territorial claim to a busy day ahead. The rural community of creature kind was resetting the natural order of things as the night shift headed for bed and the day shift repopulated a valley in all the pomp of its summer plumage.

Heading for the crack willow couch, Kuschta sensed her life had changed. She had no expectation of finding a familiar body settled on the spongy, rotten wood. She was alone, and that, for now at least, was the way it would be. Pushing herself head first through the willow screen, she settled into the couch. Hunger was now her greatest concern. For a while she stared out from her hide as the river slowly woke up. A trout sipped at insects caught in the surface film. Damselflies began their hovering dance. The kingfisher took up his perch ready to feed. Bees created a symphony of buzzing as they sucked the nectar from the buttercups that blanketed the water meadows. As the familiar sounds and the warmth of the morning overtook Kuschta, she slowly drifted towards sleep, but not before resolving to find food as soon as darkness came.

It is fitting that Kuschta spent her first nights alone in the hollow of a tree, as she took her name from the myth of Native American tribes who both revered and feared otters. In legend otters dwelt in the roots of trees, transforming themselves into human form at will. In some tribes the kuschta, which literally translates as ‘root people’, were friendly and kind, leading the lost or injured to safety. But for other tribes these shape-shifters did so for evil intent, to become the stealers of souls by guile, luring the naïve or unsuspecting away from home where they were transformed into otters, thus deprived of reincarnation and the consequent promise of everlasting life that was at the core of Native American belief. Interestingly, dogs were considered the best protection against these ‘land otter people’, being the only animals the kuschta feared as their barking would force them to reveal themselves or flee. Today dogs still have a similar effect on otters.

By the time dusk arrived Kuschta was ravenous, as hungry as she had ever been in her life. In all probability she had never gone this long without food, so just as soon as the darkness felt safe she pushed out into the river. The eel pool was the obvious destination, so she swam with purpose, confident in her ability to hunt down a meal solo; after all, she’s been doing so for much of her life, but in the wild nothing is ever certain. Fish are faster than otters, which Kuschta had learnt very early on – over the first two yards a trout will always leave an otter trailing in its wake. Hours of fruitless pursuit had left her exhausted on the bank, reliant on the success of her mother or sharing with her siblings. But over time, through observation and imitation, she figured out that over ten yards, when stamina tells, the odds would start to tip in her favour. Add in a bit of stealth and suddenly she had a winning formula.

Cruising the pools, she’d use her super-sensitive whiskers to pick up the vibration of a fish. Arching her body, she’d dive head first, deep under the surface, preparing to hunt the fish from below. Sometimes if the moon was bright she’d see the outline of the fish above her, but more often it was her whiskers that were her guide. Propelling herself upwards with her webbed feet and powerful tail strokes, she’d accelerate towards her prey. For a moment she’d have the advantage of surprise, but fish are no slouches when it comes to sensing vibration; their lateral line, which runs the length of their body, is as good as any whisker sense and usually enough to grab that two-yard start. From then on it is ten seconds of life or death for the fish, success or failure for the otter. The two swim, leap, crash, weave and dive, creating mayhem in the pool as Kuschta tries to grab the fish in her mouth.

You might be tempted to think that the otter holds all the cards in this showdown, but in truth failure is the accepted outcome. What otters have is total determination; that instinct to try and try again. There are few hiding places for a good-size fish. In general they have to keep moving to survive. Movement equals vibration. Vibration equals discovery. When an otter has found a fish once, it will find it time and time again. Unsuccessful chases will be followed by more unsuccessful chases until, through tiredness or error on its part, a fish ends up clamped between those whiskery jaws or the otter accepts that the fish has won the day this time.

Approaching the eel pool, Kuschta aligned herself with one of the gaps in the weir that spouted water into the pool, knowing this to be the perfect cover for her attack. As she flopped over the lip she allowed the current to carry her out into the midst of the pool, the turbulence masking any evidence of her arrival. She really didn’t have to expend much effort along the way, just use her tail and paws to course correct until the back eddy bought her to a gentle halt. In the still night dark she hung in the water, its pace now very slow as the champagne bubbles dissipated around her. Weightless and drifting, Kuschta was alert to the slightest movement – her whiskers, her eyes. A few yards off she sensed a fish coming her way, but before she could dive, it turned away. The fish were there, that much she knew. All she had to do was find one.

Calm to the task, Kuschta curved her body, using a slow tail beat to rotate in a wide circle, using eyes, ear and whiskers to scan the full circumference of the pool, the eddies, bubbles and swirls breaking the flat surface. Somewhere out there she sensed, rather than saw or heard, another fish slowly swimming away, unaware of her presence. Perfect. She arched her back, slid beneath the water, and when she was a few feet submerged she started to home in on the fish in a rising diagonal. As she gathered speed the distance between them narrowed. Advantage Kuschta. But not for long. The fish felt her coming as the bulk of her body pushed a sonic bow-wave ahead which reached him just before she did. That fraction of a second warning was enough to alert him to the danger. In a moment he went from languid to panic, his body squirting forward, flexing for speed as if electrified. Accelerating away, the gap widened, but that suited Kuschta just fine. The more the fish panicked the easier he was to track, as the chatter of vibrations came back to her through her whiskers. She hung on in his wake, letting her stamina blunt his speed. Across the pool they went, the distance narrowing with each yard as they headed for the far bank. For the fish the bank equalled safety, a chance to throw off his pursuer amongst the roots and undercuts. Kuschta knew this and put on extra speed to close the gap, getting herself close enough to lunge at the fish. In that final effort she bunched her body, then exploded forward, but just as her nose brushed the flank of the fish it twisted away, her jaws closing on nothing but water.

Kuschta surfaced for air, emitting a sharp cough as otters are apt to do after underwater effort – whether it is a reflex action, a clearing of the air passages or a prelude to a sharp intake of breath, I do not know, but it was to become one of the sounds that I will forever associate with otters. Head in the air and eyes shining bright, she readied for the next attack, wheezing as she gradually recovered her breath. She knew she only had to wait. All stirred up by the chase, the fish would be radiating vibrations, uncertain where to hide or swim. It would not take long for it, or maybe another fish equally disturbed by Kuschta’s presence, to come back into her orbit. And sure enough, one came straight towards her at speed, whipping past and giving her only enough time to dive down at it. But her effort was more sound and fury than effect, as the fish was already out of danger by the time she had completed the lunge. Unconcerned, she paddled after the fish; sometimes she kept it close, other times it faded into the distance, until she picked up the tell-tale signs again. Around and across the pool they went. The pursued and the pursuer. For the trout it was about staying alive. For Kuschta it was about food. For both, in different ways, it was about survival.

Soon Kuschta sensed the fish was tiring, the sprints of flight slowing with each passing chase. Suddenly she felt the fish to her right, the two of them swimming parallel. This was her chance. One swift dive, turn and boom and she’d grabbed the fish by the soft underbelly. As the fish tensed and twitched she drove her teeth deep into its flesh, asserting her grip. She knew it wasn’t the perfect hit, more to the tail than the head, allowing the trout to thrash and twist its body, but changing the grip of her jaws was no option. She’d learnt from bitter experience that was how meals escaped. So with the trout whipping about her head she swam for shore, digging her sharp claws into the bank to heave herself and the fish onto the grass. Subduing the fish by shaking it hard, Kuschta held it down with her front paws, let go of the belly and bit hard behind the head, extinguishing all life bar a few death twitches.

Otters don’t gloat in victory, they simply get down to the job in hand, consuming the capture. Kuschta was too hungry to care anyway, tearing into the flesh, eating as much and as fast as she could. After twenty minutes, with the head and the best end of the fish safely in her belly, she paused to clean herself, licking away the smatterings of blood, scales and flesh. Silent and content, she settled down to rest for a while before she would finish the fish then head back to the rotten willow. But a noise in the distance changed all that. Up on the beam she knew so well, a figure appeared. An otter – bigger than any she had ever seen before. It first sniffed suspiciously at the ground where she had lain then tested the air. She froze as it held its head in her direction. For a moment she thought it was going to leap into the pool and head directly over to her, but it was distracted by another otter, more the size of Kuschta’s mother, which came up by his side.

As the two nuzzled and groomed at each other’s fur, Kuschta knew her time in the only place she had ever called home was over. The larger of the two was not an otter she recognised; the other may have been her mother but she could not be sure. Though part of her yearned to do it, she suspected, quite rightly, that no good would come of her revealing her presence. It was time to go. Edging away from the river, she headed for the woods and, keeping the sound of the water just within earshot, continued downstream for an hour or more. Moving on land is tiring for otters; yes, they can run quicker than you might think, with a gait not dissimilar to that of a greyhound, but given a choice, it is water at times of flight. Back in the river, Kuschta swam as fast as she could. Soon there were no more familiar landmarks, every fresh stroke taking her to a place she didn’t know. In the space of two days and two nights she had lost her mother and her home. She was alone and afraid.

At dawn she could swim no further; her body was chilled to the core by too much time in the water. Dragging herself onto the bank, she shook herself like a dog, sniffed the ground and then padded through the long grass, occasionally stopping to sit up and look around. Soon she spied a dense clump of brambles not far from the edge of the river. Finding an opening, she pushed her way into the middle, the tendrils, laden with bullet-hard red blackberries still a month away from ripening, swinging closed behind her, keeping her safe from prying eyes and unexpected visitors. It was far from perfect, but for now, with the ground dry and the leaf mould soft, she gave into the sleep that her exhausted body craved.

Otters are not by choice nomadic, but in the months immediately after fleeing the eel pool Kuschta had few choices but to become so. Like all her breed, when fit and fed she was capable of covering great distances, but that was borne out of necessity, not choice. In her search for a place to call home, Kuschta found each successive territory occupied, and was forced to move on when her arrival became patently unwelcome.

That is the thing about otters. We tend to think of them as gregarious, social animals – the Disneyesque vision of a pellucid pool, ringed with trees, which is fed by a tumbling waterfall where the pups frolic and play whilst the parents keep an all-seeing eye as they sun themselves stretched out on the warm rocks. However, the truth is somewhat different; otters are really not very social animals. Once Kuschta had adapted to a life alone, it was the life she preferred. Of course she would join with another when the time for mating arrived, splitting immediately afterwards to become the dutiful single parent for as long as required, but once the pups were gone she’d return to the solitary life, the default choice for her species. Being non-social is all very well but it does require a space to claim as your own, and that was increasingly Kuschta’s problem. Everywhere she went was occupied by people or otters.

A millennium of persecution has taught the otter a lot about people, not much of it good. Otters have learnt to be invisible, shunning the day and hugging the night. Where the river took Kuschta through towns she just kept swimming by night, staying in the shadows, so that people were oblivious to her presence. Sometimes she was forced to hole up for the day, but it was never a problem; culverts, outflow pipes and all manner of structures were plenty good enough for a layover until darkness returned. At first this was all very unfamiliar, but in her travels Kuschta soon learnt that she was, at least in respect of animals other than her own kind, top dog. The apex predator, as the biologists like to call species such as Lutra lutra. There might have been a time when wolves or bears roamed the British Isles that otters had something to fear, but today they firmly reside at the top of a food chain, upon which no other creatures prey. It is a pretty exalted place to be, but in every society – even within that of apex predators – a structure evolves with the weak at the bottom and the strong at the top. Kuschta, still a few months off physical and sexual maturity, was trying to find her place in that new order.

Otters are territorial creatures, but claiming homelands in a way that is really quite unusual, for despite all the attributes of a creature fit for fighting – lean, lithe, strong claws and sharp teeth – they choose another path. For aggression read avoidance. Apart from the rare occasion when two rutting males clash, they are the most anti-confrontational of animals, a trait which they achieve by the delicately phrased term of sprainting.

Spraints, to put none too fine a point on it, are defecations – markers set out along the river bank telling of who ‘owns’ which territory. If you are an otter you can tell a lot about your fellows from a simple sniff – age, sex, status, fertility – they are all there in the musky scent. Marking out your patch is a neverending task. Typically otters will cover anywhere from a quarter to a third of their territory on any given night, making thirty to forty deposits, far more than required by any digestive tract. Maybe this goes some way to explaining the origin of the word spraint, which comes from the French épreindre, which means ‘to squeeze out’. The effort is neverending because the scent only lasts for just so long – a few days at most – requiring regular reinvigoration. Otters are creatures of habit when it comes to these marks, using the same place time and time again. Keen otter trackers will go to great lengths to find piles of dry guano, the remains of up to two hundred spraints, topped with a shiny new marker. Otter huntsmen were keen aficionados; they knew that otters returned to the same spots generation after generation. It is no surprise that these dropping piles were ideal for encouraging the hounds to pick up the scent. A huntsman would not be averse to a bit of scenting himself, squeezing the manure between his fingers to judge its age, along with a judicious sniff. Some hunters claimed similar nasal powers of identification to that of the otters themselves, announcing to the assembled hunt followers that they were on the trail of such and such an otter. You do wonder whether this was more about mystique than fact.

Kuschta became increasingly impatient as the new day wore on; night was a long time coming and she was hungry. In her temporary hide she pawed the ground for something to eat, but it was more of a distraction than a practical alternative – bugs and earthworms held little appeal. The previous night had been a hunting disaster; one small perch and an unlucky frog that she had stumbled across. As the sky started to darken she took her cue from the bats; if it was dark enough for them it was dark enough for her, so as soon as they began to flit across the blackening skyline, Kuschta was on the move. For days now she had been travelling ever upstream, keeping close to the river. Occasionally she had been driven inland by people, dogs or other otters, but essentially her path was that of the river bank. Sometimes she’d reach a confluence, the junction of the river offering a left or right choice with her taking the one seemingly least travelled.

Her progress was always halting, stopping to smell each spraint she came across, the new evidence to be considered before a decision could be made. Male or female was the first marker scent she’d evaluate. At first glance a male might spell bad news, but not necessarily so. A male otter will cover a huge territory, many times that of a female, so he expects to find a number of females within ‘his’ territory. On that basis she’d pose no surprise, interest or threat, being as yet still too young for mating. Females, on the other hand, were a different thing altogether. Though Kuschta offered no physical threat to a mother otter, who would be more than capable and willing of protecting herself and her pups, Kuschta would definitely be seen as taking a share of the neighbourhood food. It is interesting that otters moderate their reaction to competition for food very much according to the season. When times are good they are happy to share, and temporary visitors will be tolerated. When times are hard boundaries are, if not explicitly protected, to be more respected by an interloper.

The freshness or not of the spraint presented all sorts of conundrums; some good, some bad. If it was a fresh male mark, it signalled that he had been here and had moved on, and was unlikely to return for a few days. Stale? Well, he might be back sometime soon. Female spraints were different; lots of the same within close proximity told Kuschta that she was probably in the midst of a family territory – better to go. No female scents, or at least only ancient ones, were more complicated. Either she had stumbled across vacant territory, or maybe, if it was a productive area, the female was going through the secretive phase that bitches are apt to experience immediately before and after the birth of a litter, as they stop sprainting for a while. They change their normal behaviour to disguise their presence for the safety of the pups, which have to be left alone for a few hours each day whilst the mother hunts. Surprisingly, during this period the greatest threat to the litter comes not from other species but from otters themselves. Postmortems of roadkill dog otters regularly produce the remains of pups in the stomach. Now whether this is more often the father or another jealous male, nobody is entirely sure, but it surely happens and in all probability, as indicated by DNA matches, it is a bit of both. The fact is, this infanticide happens more often than we might like to believe. The reasons? Again, we don’t really know, but one can best assume that the mothers would not have evolved such a protection strategy without good cause. For otters the genesis of single parenting may have many reasons.

But spraints are more than just markers of territory; they are, in twenty-first-century jargon, food management tools, used by otters in all sorts of ways. Firstly, the spraint can say ‘I’ve just fished this pool, so give it some time to recover or we’ll kill the goose that lays the golden eggs’. Or secondly ‘Don’t waste your time and effort. I’ve caught all there is to catch’. Conversely, a pile of spraints, the most recent a little old, tells the otter that historically this is a productive spot now ripe for hunting. And no spraints either mark virgin or barren territory – proceed as you choose. Likewise, the contents of the spraint, be it the remains of fish, eel, crayfish and so on, tell of what there was, and maybe there still is, to eat. Kuschta was still a few months off appreciating the final piece in this spraintology jigsaw, which tells of females ready to mate and males on the prowl. Her time for this would come soon enough; for now she was struggling to find that elusive home territory.

If you sat an otter down to discuss the whys and wherefores of territory, the first words out of its mouth would most likely be ‘It’s complicated’; for Kuschta and her kind the enforced itinerant months were a progression from ignorance to understanding. When she was young the home patch that her mother had carved out was uniquely theirs; as far as she was concerned, the otter world did not extend beyond her immediate family. If other otters, including her father, strayed close, her mother would ward them off long before they could approach the pups. But now, on the road, she had to negotiate her way through a competing world.

To the human eye it is nigh on impossible to tell where the territory of one otter starts and another ends. There are no clear dividing lines; otters are certainly no respecters of man-made boundaries and there is little in nature that will hinder their progress. Otters are legendary for the ability to cover enormous distances in a single night; twenty miles is well within the scope of most, but herein lies the problem – that twenty miles is along a river, inevitably passing through a multiplicity of other territories that rightfully belong to other otters. But our mustelids have created a social policy that some humans could do well to learn from. At the core is the family territory, which is sacrosanct. It is always accepted that other otters will ‘pass through’, but woe betide any that pause or, worse still, try to stay. There is no excuse for ignorance; those spraints are flags enough to say who lives where and why. Single female otters, on the other hand, are more relaxed; after all, they don’t have pups to feed or defend so their territories are looser, overlapping at the edges. That said, they will have carved out a portion of the territory that they regard as ‘theirs’, expecting other otters to keep away. Males spread themselves much wider, their territory taking in maybe three, four or five females’ homelands, which they continually traverse, taking as much as a week to cover the entire area. Of course, this assumes there is only one dog otter in any given super-territory. But nature would not allow that – replacements and competition are always required. There will be more than one male sharing the territory, a potentially ruinous situation with competition for land, females and food. But otters have evolved a daisy-chain hierarchy where each lesser male follows in the footsteps of his immediately superior male, organising his life so he precisely avoids meeting the others. Of course, there are clashes, violent fights and changes in the order. No otter chooses to be of lower caste, but, given a death or some other departure, there will be a shuffling of the pack.

It is a fascinating animal culture; despite being solitary creatures, otters as a breed have survived for 20 million years because, probably without realising it, they look out for each other. Avoidance saves wasteful territorial disputes. Designated family homelands allow pups to thrive. Complicated spraint markings spread out the population, avoiding overcrowding, preserving food stocks and limiting disease. Wandering males mix up the gene pool. For the perfect evolution you could not write a much better script – it is just a shame, as we will see later, that humans came into the midst of this with near-fatal consequences.