Читать книгу Facing the Lion - Simone Arnold-Liebster - Страница 11

Discovering Death and Life

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

Discovering Death and Life

T

he days grew shorter, fog crept through the fields, the dahlias hung their heads. We children ran after leaves and gathered chestnuts. The boys used them like missiles, forcing us girls to hide. I just hated them!

People headed toward the cemeteries in carriages full of white and pink chrysanthemums. It was Halloween and people were going to visit the graves of their loved ones. This meant another family gathering. Even Aunt Eugenie would come from far away.

Again our neighbors would mistake her for Mum. That tickled me. She had the same black hair, yet her complexion was more like her amber necklace, and her eyes were like dark cherries. But her cheerful personality made her look like Mum’s twin sister. And that was the way both sisters felt. She was like a second mother to me.

Grandma and I went to the Oderen cemetery to clean the graves. Aunt Eugenie carried a huge pot of chrysanthemums. She went to her husband’s grave and cried and prayed.

“Grandma, why does she cry?”

“Your uncle died not long ago. They were only married three years.”

“Did he drown in the river?”

“No, he died of tuberculosis.”

“Mum told me death is the door to heaven.” I was a very little girl when by mistake I had gone in the room of my grandmother’s father. He was lying with his eyes closed and looked like he was praying, surrounded with crowns made of artificial flowers. Four huge candles gave a soft light, and the smell of incense filled the room. He was on his way to heaven, they told me. But now in front of the grave, my feelings changed.

“Grandma, is the tomb the door to heaven?”

“It also can be the one to hell.”

“I have seen the smoke of hellfire coming from the basement of Dad’s factory. I always make a big detour when I see it!” Grandma smiled, took my hands, and said a prayer, and Aunt Eugenie joined in with us.

“Why do you pray? Do the dead hear?”

“Yes, they do, and they can help us if they are not in purgatory.”

“Purga– what?”

“Purgatory is a place where the mean things we do, called sins, are burned up by fire. Only saints go to heaven right away.”

“Who kindles the fire?”

“Lucifer, the archangel. Because he was full of pride, he had to leave heaven and become the guardian of hell and purgatory.”

“Grandma, it’s cold here. I’m shivering. Let’s go!”

We called the cemetery the “church court” in Alsace. When we left, the graves were in the shadow of the church; there were so many flowerpots, all those people must have been saints!

When we arrived back at Grandma’s house, my cousin Angele had not yet arrived.

The family finished preparing for Halloween. Uncle Germain carried the table and chairs into another room. Grandpa brought in big logs for the fire. My mother and Aunt Valentine prepared chestnuts for roasting, while Grandma lighted a big candle next to a crucifix that had been placed between the two windows. The whole family got down on their knees. A person’s name was called. “We pray a Rosary for his soul.” Those prayers sounded like a murmuring complaint; the sighing wind in the chimney and the crackle of the fire made it seem even gloomier. I studied each one’s attitude.

Peeking, I saw Uncle Alfred’s eyes open. “Uncle, why don’t you pray correctly?”

“You wouldn’t see me if you would do it properly yourself,” was Uncle Alfred’s quick reply. But I knew how to do both—pray and peek. The firelight of the lone candle danced on the ceiling. Was it the fire of hell? Purgatory maybe? Outside, a pale moon darted in and out of the clouds, casting strange, spooky shadows. Were they ghosts? An uncomfortable feeling came over me. And there was no end to the praying. My knees were hurting. The last log burned down. No more exploding chestnuts. The room got darker. The candle started to shiver, like me. A long black column of moving smoke made all kinds of figures. The flame was now down to the holder, its very last flickerings illuminating the picture of Mary. There she was, neatly framed. She held the babe Jesus, who had a ball in his hands. Her chest was open, showing a bleeding heart. As I looked at the heart, it was quivering and bleeding even more. Then she finally disappeared in the darkness.

Somebody got up and switched the light on. Uncle Germain brought the table and chairs back; cups and milk were brought in, while my mother and Aunt Valentine peeled the roasted chestnuts. To me, the nuts had no taste.

DECEMBER 1936

As I stood on a chair, my mother knelt down, pinning the seam of the vaporous white tulle angel costume with two wings attached to the back. I repeated my lines over and over again. Mademoiselle had asked my parents if I could be in a group of Catholic youth called the “Skylarks.” Under the direction of our parish priest, I was chosen right away to have a part in a theater play for Christmas—as Gabriel the archangel. Little by little, I got so involved that my Halloween nightmares of hellfire were extinguished. I felt sunny again.

I was so excited that it was hard to sleep. It was December 24th, the night the Christchild would come. I was determined to stay awake. In the middle of the night, Mother called me out of bed. A soft light flowed from the dining room. Mother combed my hair, had me put on my housecoat, and said, “The Christchild came by. Let’s go and see what he brought you.”

I hardly could believe it! In the corner of the room, he had put a small pine tree adorned with little burning candles reflecting in glass balls and covered all over with glittering wreaths. Under its branches were some oranges and nuts. As I got closer, I found a baby carriage and a beautiful doll. “Mum! Dad! Look! the Christchild knew exactly what I wanted!” Mum was right when she told our curious neighbor who had asked what I had ordered: “A gift cannot be ordered, and the Christchild knows what Simone desires and deserves!”

The doll sat there with outstretched arms, pleading for a mum. And the Christchild knew I yearned for a daughter. I took my doll and right away named her Claudine.

The next day was our Christmas performance. The curtain fell after the first act. More than the applause from the audience, the teacher’s congratulations gave me confidence for the longer act to come. So many times I had dreamed that I was on the stage with an open mouth and no voice!

During the intermission, Aunt Eugenie came to get me. “Leave your angel wings here and come with me. You have plenty of time.”

Aunt Eugenie worked as a governess for the Koch family. “The Kochs want to meet you. They are with your parents in the loge on the balcony.”

In the dim light, I could hardly see the balcony. It had a strange musty odor and red velvet chairs; the place was tiny. Mr. Koch got up, bent over, and extended his right hand to me. He said, “I’m honored to meet such a nice, capable little lady.” He took my hand and kissed it gently. I didn’t know what to do with myself. Happily, Mrs. Koch added, “and how beautifully dressed too!”

“Yes, I am, because Mum made this dress for me!” I loved my black velvet dress with a garland of little pink roses all around the little jacket, and I was proud to let everyone know about it.

Suddenly the loge door opened. Henriette, a poor mentally ill girl, stood in the doorway, a basket hanging around her neck. She trembled all over. With begging eyes, she pushed the basket under someone’s nose. “Buy a little raffle, please, please. You will win.” Everyone in the loge bought one, then she ran out. She went to the next loge. A solitary man waved his hand and shook his head “no. ” She blushed and ran away. Poor girl! How terrible! I felt so bad for her. Mother, disgusted, stared at the man. I followed Mother’s eyes and recognized our parish priest.

The bell rang for the next act. I had to leave. The lights slowly dimmed. I passed Henriette, coming back down the hallway. The priest had called her back in.

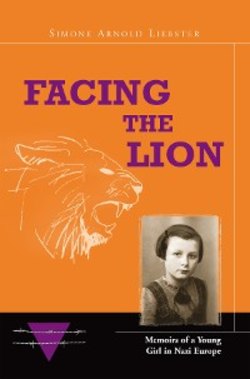

Simone with Claudine, her doll, Christmas 1936

The play was a success. The curtain fell after the last act, but rose again right away. We were called back onto the stage. Some of us had to step forward. The applause filled my eyes with tears. The city theater was packed and everyone was clapping. I felt like running away, yet my feet were as heavy as if they were nailed down. The red velvet curtain came down again. Everyone left, but someone had to take me by the hand. I was worn out and I longed to go home and crawl under the covers.

Mum, who had come behind the stage, kissed me and took me in her arms. I felt her body, stiff and tense. Something had made Mum very upset. With indignation, she said to the theater manager, “Simone will not be in the play again, and I am taking her out of the Skylark girls group. I do not raise a girl to expose her!”

“What do you mean?” the manager asked with surprise.

“You should have seen what happened in the loge next to us!” (The priest had abused Henriette.)

As we walked away, Mum said to me, “Now, you have your daughter, Claudine, waiting for you at home. She needs you. This is better than the Skylarks!” I was so tired. Mother could tell. She was wonderful!

“Yes, I have to take care of Claudine. Poor girl, she is all alone at home!”

Claudine sat next to us while I learned how to knit. Zita was there too. Looking out the window, I saw snow mixed with rain.

The rain spoiled the beautiful, smooth white blanket of snow. Our feet got wet and cold walking in the slush on the way to Aunt Eugenie’s. Her mistress, Mrs. Koch, had asked her to invite me for their Christmas Eve, some days after the 24th of December.

Mother had given me a lot of orders—always the same ones over and over again. I knew them all. Be polite. Don’t put one foot on the top of the other when you stand. Don’t touch the furniture. Don’t serve yourself. Don’t chew with your mouth wide open. Don’t go in a room if you’re not invited. Don’t put your elbow on the table and hold your head. Don’t play with your hair. Don’t swing your legs when you sit. Don’t, don’t, don’t!

The big villa with marble steps, crystal mirrors, and a colorful carpet made me feel embarrassed. The odor of pine, candles, chocolate, and cake; the loud laughter of the three sons and their cousins; a pine tree reaching up to the ceiling, underneath a mountain of colorful parcels—I wanted to run away.

“Come in, Simone. Don’t be shy. The boys won’t hurt you.”

Aunt Eugenie introduced me to the three boys and their cousins, who clearly were not interested in meeting a girl. Boys are all the same, just like the ones at school who threw chestnuts at us girls. I don’t like boys, I thought.

I sat on a chair so high that my legs dangled. My hair bothered me. My aunt smiled and gently but firmly put one hand on my knee to stop the swinging. She took my hand out of my hair. I blushed. Did anybody else see it?

Mrs. Koch, wearing a wonderful lace dress with a long, three-row necklace, sat next to me. Speaking in French, she said: “Simone, Father Christmas (Père Noël) has brought something for you.” And taking my hand, she led me to the beautifully adorned pine tree standing opposite a big lace-covered table. The crystal glasses and silverware reflected the dozens of candles on the tree. This fascinated me more than searching for my gift among the many packages under the tree.

My aunt came to my rescue. “Simone, look for your name.” Under the tree was a manger like the one we had at Christmas in church, but today was not Christmas anymore. Why was it there? My gift was a small box; in it was a wooden man, 20 centimeters high, with a slot in his back. “This is a money box. You put your savings in that slot.” I opened it. It was empty.

I went back to my seat holding my package tightly. The maid in her black dress and white apron came and offered me some sweets. My aunt encouraged me to take one. I was very uncomfortable.

Finally Mrs. Koch said, “Eugenie, in ten minutes a streetcar will be leaving for Dornach. You may accompany the young lady.” What a relief! The maid brought my winter coat, my little polecat fur, and my felt hat. She tried to dress me.

“Oh, no. Please, I’m a big girl now. I can do it myself.” Everybody smiled.

“A true little lady,” Mrs. Koch said. She followed us to the door. Through an open side door, Mr. Koch nodded his gray head to me. Behind him I saw a table with drawers and golden feet and bookshelves up to the ceiling. What kind of room is this? I wondered.

Snow had fallen again. The yellow light shining through all the many windows made the Koch’s house look like a home in a fairy tale.

On the way home, I asked Aunt Eugenie why the Koch’s called the Christchild “Father Christmas,” why he brought me a gift at the Koch’s home instead of mine, and why he came on a different day. Aunt’s answers seemed incomplete. I was totally confused.

I was happy to return to school after the holiday. However, the classroom was cold. It took quite a while for the newly lit fire to give off some heat. Madeleine, Andrée, Blanche, Frida—none had had a pine tree for Christmas. Each only got one orange and one apple with some nuts, “because,” said Mum, “they are poor.”

That night, under my covers, I accused the Christchild. “Why do you treat rich and poor differently? Why did you give the Koch boys trains, books, games, cars? They got so many presents that they were tired of opening them—and yet you brought nothing, absolutely no toys, to most of my schoolmates? This is injustice, yes, injustice!” Wasn’t that how Dad had explained injustice— favoring the rich over the poor?

I decided to correct that terrible injustice. So every day I bought chocolate or cookies to give out at school. One day, passing by a toy shop, I saw a little doll sitting on a baby chair. I decided to buy it for Frida. She had been completely forgotten at Christmas. I went in and asked for the price: five francs. “Please hold it for me. I’ll get it this afternoon.”

I went home for lunch. After lunch, Madeleine came to call for me so we could walk back to school together. But Mum asked her to come upstairs. “Madeleine,” she said, looking at me, “would you have a thief as a friend? Please tell Mademoiselle that Simone will come to class later.”

Obviously Madeleine didn’t understand. Me, either! She left without me.

“Give back the money you have stolen.”

“Mum, I did not steal!”

“Don’t make it worse by adding a lie.”

“I am not lying. I didn’t steal anything.”

Quickly she put her hand in my pocket and pulled out a five-franc piece.

“And what is this?”

“I took it, but I did not steal!”

“Can you explain that?”

“Yes! I just had to correct the Christchild’s terrible injustice to Frida. I wanted to buy the doll for her.”

To my surprise, Mum bought the doll and put it on my shelf next to my bank from Mrs. Koch.

“Girl, stealing is taking something that is not yours, no matter what you do with it. This doll is going to remind you. It will stay there. Don’t dare take it away. As long as you leave it there and do not steal again, I won’t tell Dad. You know, he had to work many hours, yes, days to earn five francs. It is going to be our secret between us two. You know how your father stands for honesty. You watch it. He has never spanked you before, but for sure he will. Never remove that doll from there if you don’t want to have a problem!”

Thursdays, we had no school and sometimes my cousin Angele would come over with her doll while I was holding class with my doll, Claudine. I took it all very seriously, repeating Mademoiselle’s civic lessons. But I had trouble explaining to the dolls the idea of conscience. I didn’t understand what it was, how it worked, how a person could lose it, or even be without one in the first place.

So one day I asked Dad, “What is a conscience?”

“It is a voice inside you that tells you what is good or what is bad.”

“Dad, my teacher said that each evening we should think about our day and what we have done.”

“This,” Dad said, “is called the examination of one’s conscience. As you grow, you’ll be able to do that. Little ones can’t do it yet.”

“I don’t hear anything. Every evening I listen. No one inside me talks. Where can I find it?” I did not want to be a “little one” anymore.

“Continue searching and listening. One day it will come. It is in you.”

“Daddy, last night in bed my legs talked!”

“What did they tell you?”

“That they wanted to turn.”

“And how did you answer?”

“I changed position.”

“Those are your muscles. But, someday, the same feeling will pop up in your thoughts, and you’ll have to listen to them and do what they tell you.”

Teaching Claudine was a serious matter to me. I was sitting in my “classroom” one day, watching Mum sew. When Dad stepped in, I was happy—until I saw his gaze fall on the little doll sitting on the shelf. I felt like Zita who, when she had done something bad, crawled under the bed!

“Where did that doll come from?”

I knew I was in trouble.

“Isn’t it cute? It is Simone’s taste,” Mum answered without taking her eyes off her work. I got stiff and ducked out of Father’s sight.

“It must have been expensive, because a miniature is always very expensive!” I was doomed! I stared at Mother. She continued sewing.

“By the way, Adolphe, talking about being expensive, did you check on the price of a new bicycle?”

“Yes I did. We can’t afford it. It’s much too expensive.”

“How long do we have to save?”

My dear mother had kept our secret. What a relief! That evening in bed, I looked at the doll and thought of my cookie and chocolate distribution; I remembered the happy faces of my classmates. Then my heart started pounding. All that money I had taken could have bought a bicycle for Dad. My heart was beating even faster. Was that my “conscience?” How could I know? I couldn’t ask Dad without giving away our secret. It was a painful situation!

The next morning, I pushed the doll out of my sight. I did so every day for days. But every evening it was back in its place. Each day my heart beat more wildly. I trembled in the morning when I would hide the little doll away on the shelf. One day I just couldn’t do it anymore. My mother’s presence became unbearable; her silence a load. I had become conscious of my conscience!

Back in the classroom, a breathtaking vision unfolded before us as Mademoiselle vividly described God’s throne. Full of enthusiasm, she spoke about the angels that God had specially created. Playing divine music on golden harps, they surrounded his throne. I yearned to be there.

“Men cannot see them because they are spirits. We cannot see spirits. They have big wings and fly through the heavens.”

After that inspiring talk, I had a hard time concentrating on arithmetic. After two hours of class work, the priest came for our religious lesson, the catechism.

He entered class at 11 a.m.

“Blessed is the one that cometh in the name of God,” he said in a ceremonial voice.

The class stood up and said, “Amen.”

“How can we get into heaven?” he asked.

That was just what I wanted to know.

“The best way is to suffer,” he answered. “Each time a person suffers, he gets chastised by God, and God chastises everyone whom he loves. So be happy and rejoice when you suffer.”

After class I went up to the priest. “My Father, why did God create angels right away in heaven while we have to suffer to get there?”

The face of the priest became menacing, his eyes fiery. With a trembling voice, he said loudly, “You are just six years old, and you dare judge God?”

“My Father, I just...”

“Shut up! You have a rebellious spirit; you are on the way to hell if you continue like that! Learn your lesson and never question it!”

I walked away slowly. I was crushed. I thought, I’m so ashamed of myself. I won’t tell Mum about my religion class today. It will make her feel bad. The thought made me cry. From then on, I never felt at ease in my catechism classes. The priest’s dark eyes and threatening voice upset me. It seemed he only knew how to talk about hell. I preferred to go to church.

FEBRUARY 1937

On Sundays, we walked down the street dressed in our best clothes. Mother had a nice hat. Dad always wore a smart beret that he touched with his right hand when people would greet him. I held on to Dad’s left hand and held my pearly covered missal in the other hand. Mother clutched her purse and her missal tightly to her chest. She greeted everyone with a nod and a smile.

“It must be ten o’clock. The Arnolds are on the way to church,” some of our neighbors said. I was very proud to see how people greeted my parents courteously.

Our church was impressive. The door was wide open. The sun’s rays came through the high windows, illuminating the golden altar and making the light from the candles almost invisible. But it was not quite the same anymore. I looked at the images. They all had dramatic faces. I could no longer look at the priest and his assistant during the Eucharist, but I kept beating my chest like everyone else while repeating, “It’s my fault, my fault, my fault only.”

It was a nice warm February day. After church, we went on an outing. “Leave Claudine home. You can’t take her along. We’ll be hiking through fields and meadows.”

As far as our eyes could see, the brown earth stretched out; some meadows were turning green.

A stork, the state bird of Alsace, walked in the swamp beside the Doller River. Zita, with her tail wagging, ran back and forth across the meadow, chasing everything in sight and playing hide-and-seek with me. The rays of the setting sun danced between layers of mist that hovered just above the grass. Suddenly in the distance, I spotted a man and a young boy crawling out from underneath the thicket. They hurried off and quickly disappeared from view.

That Sunday evening before going to bed, Mum sat down to talk with me. I felt uneasy.

She looked at me tenderly but seriously with her deep blue eyes. “I know you go to church every morning to pray before going to school, but Dad and I ask you never go to church without us!”

Her words felt like a slap! “But why, Mum?”

“The church is a very large place, and there is not much light. A bad person may hide himself and then attack you.” Taking my chin in her hand she repeated in an undertone, “Never go to church for prayer by yourself, all right?”

On Monday morning, I passed by the church. My heart was pounding. I obeyed my parents’ order, but I wasn’t happy about it. At school, we had the usual Monday routine, the story of Saint Theresa de Lisieux, the review of our homework (I had the best marks again and Mademoiselle’s compliments), and Frida was there. But now she had to sit in the last row all by herself because of her cough. The sky turned brownish gray and snow had started to fall. We had to turn the lights on again. By the time the morning class was over, a snow storm was in full force. We had to walk backward alongside the houses. Frida had a hard time fighting against the wild wind. She coughed constantly, gasping for breath.

“I didn’t go to church, Mum!” I whispered in her ear as I kissed her.

“I know you are an obedient girl.” Mum brushed the snow off and brought me nice warm slippers, and I told her about the struggle we had to get home.

“And you know, poor Frida has to sit in the last row in class, all alone by herself because she coughs.”

“When she coughs, turn your head away from her!”

In the afternoon, the sky got brighter. Frida was absent from school again. The empty bench in the back of the class brought home to me what sickness could do. I decided that before becoming a saint, I would first become a nurse.

Sitting in the class, I could see the sparrows across the way, perched on the ledge of the church window. I imagined the rays of sunshine passing through the stained glass, illuminating the altar. But I couldn’t go in.

Under my covers, I fumed against my parents. I tried to get Dad to give me permission to go to church. “What did your mother tell you?” And, of course, he backed her up.

Why did my parents always stand up together against me? When Mum said something, Dad stuck by her. If I asked Mum about something, she’d say, “Did you talk to Dad? If not, we will do it together!” There seemed to be no way around it. I just couldn’t sleep.

My parents were sitting in the salon as they did every evening, Father reading aloud, Mother knitting. But now they were both talking. Maybe about me—I thought for sure it was about me. I got up to listen, but my heartbeat was so loud that I went back to try to listen from my bed.

They were talking about religion. It was hard to follow; often their voices disappeared. “Adolphe, it is unacceptable, impossible that God is willing to come down in a Host that is elevated by such dirty hands as the priest’s.”

“Emma, we humans have no right to judge God and...”

This conversation was hard to understand. I covered myself up again. But I wondered about the priest who didn’t know that he had to wash his hands before he said the Mass!

I stood by the side door of the church. My heart raced. “This is the house of God. There can’t be a danger in there, can there?” I opened the door. The church was empty and gloomy. I quickly closed the door and left! By the following day, I had made up my mind. I would take the holy water and quickly make the sign of the cross, walking on my tiptoes and crouching down to hide behind the church pews. In front of the altar, I would quickly kneel and apologize that I could not stay, because I was not allowed to stay in the church alone. I would cross through and go out on the other side.

My jumping heart almost stopped me. The door made a grinding noise. I shook all over. The faces of the saints seemed to move. In front of the altar, I was breathless. By the time I got to the other side, my legs vanished. I thought I heard a voice in the nave. I ran out the side door as fast as I could and slammed the door behind me.

My conscience had been in turmoil over whether or not I should again visit the church alone. I came to a decision. “God is above my parents, and they don’t know my goal—I want to be a saint.” It was my great secret. I was ready to pay the price and face my parents’ disapproval. It never came to that because they never found out about my secret visits.

I had been consecrated to the Virgin Mary since my baptism and was to be present at the procession. The priest would walk under a canopy carried by four men. He would hold a golden image of the sun upon his face, and the girls would throw rose petals in the air in front of him. What a sacred service that was! Mother made me a white organdy dress with a light blue belt. She bought some new shoes and a rose crown for my head. I couldn’t wait! But then, suddenly, a bad cough canceled everything. I had never been sick; why did I have to come down with a bad cough? Was God mad at me? Mother gave my special outfit to another girl! I burned with jealousy! Three days later I felt well enough to go out again. That made me feel even worse.

When I went back to school, Frida was still absent. The doctor said she couldn’t come to school until her cough cleared up. Each day, I would call out to her, and each day her house remained silent.

Passing by her little house, I saw pots of beautiful white flowers in the backyard. Finally someone had given Frida a little attention.

Mum sent me to Aline’s shop to buy some sugar for our strawberries. I climbed up the four steps into the grocery store and stood behind a lady wearing crocodile shoes. She was tall and wore a summer overcoat—a true lady, so different from the women on our street.

As I saw her left hand in a lace glove, I was breathless. Here she was—the beautiful lady that I so admired! I must have stared with my mouth open. Good thing Mother didn’t see me.

Aline whispered, “Simone, don’t gape like that. The lady has eaten too many cherries and drunk water.” What a disappointment! Didn’t that fine lady know any better? I hadn’t noticed her big belly before. I saw only her nice blouse with that beautiful necklace, but now I realized that her stomach was so big she might burst at any moment. I stepped aside, running away as soon as I got my purchase, leaving that stupid lady behind!

“Simone, why didn’t you take Zita along to the store?” Mum asked.

“Zita is sick, and so is Claudine.” I was a nurse and Mother had made a special outfit for me. Mother said, “But this is only make-believe. You still can take Zita out. She needs it.”

“I’ll dress her and put her in Claudine’s carriage because she’s sick!” Mother laughed. She knew that I loved to dress my doggy, put her on her back like a baby, and surprise passersby with her.

Simone as a nurse

“But now Zita badly needs to be on her four legs.”

“But Mum, she is really sick!” I was the nurse. I knew better than Mum.

“How do you know?”

“Can’t you see that every day her head gets smaller?”

Mother had put the sugar on the strawberries. “You see, all the juice will come out and dissolve the sugar. We will cook it when we come back from the garden.”

We had a nice view from the garden. On the horizon on one side of the hill, we could see the blue line of the Vosges Mountains; on the other side, the Schwarzwald Mountains, and a bright sun too!

“Keep an eye on Zita. She loves to make holes in the ground.” This wasn’t an easy job. When Zita smelled a mouse, she was determined, and she was strong too. I had a hard time pulling her out by her back legs.

Suddenly, night climbed up behind the trees. We gathered up the garden tools quickly. I had tied Zita on her leash for the walk back home. We heard noises like the wind and saw a fire-red sky. A dark cloud raced over our heads. Mother took me by the hand. We had to run for cover to keep from being harmed by the “fireworks.” A farm was ablaze!

Fiery sprays jumped out of the huge flames, sparking little fires in the dry grass. We saw chickens running all over the place; some were already on fire. The cows and the pigs couldn’t be saved. All the fire engines from the city arrived and sprayed water out of long hoses to wet down the farmhouse and the neighbors’ homes. The firemen’s helmets reflected the flames, their faces were red, their clothes dark. A terrible crash rekindled the fire, and the desperate cries of all the animals inside were silenced.

When we were permitted to pass by, the charred beams were still smoldering. The air was heavy with smoke for a long time.

I came home freezing. I couldn’t eat or play. Mother suggested I go to bed because I had a fever. Zita, too, was all upset and lay down next to my bed with wet eyes. It wasn’t bedtime yet, but Mother said, “Get a good night’s rest and you’ll feel better.”

But the night wasn’t “good.” I saw fire everywhere even when my eyes were closed. In my dreams I heard the terrible cries of the burning animals. Mother decided to sleep with me.

The next day was no better. “Mum, did Lucifer burn the barn and the animals in it?”

Mother named all the different ways that fires could start, but it didn’t take away my fear of hellfire. Dad tried to distract me by encouraging me to do some painting, but I was too restless.

Even though the weather was nice and warm, Frida was missing from school again. “Mademoiselle, why can’t Frida come to school?” Instead of answering she caressed my hair.

“Is she still coughing?”

“Oh, no, she’s not coughing anymore. She’s in heaven now.”

“That’s why.”

“Why what?”

“I saw the pots of white flowers.”

Passing in front of her modest home with the shutters closed, I started to cry. The flowers were withered. They too had died. I just couldn’t look at the house anymore. My sadness about her departure for heaven made me cross the street. Yet I was relieved for her. She didn’t cough anymore but would play harps sitting on a cloud. Could she see me?

Catechism class—what would the priest talk about today? “It is necessary to make a distinction between hell and purgatory. When a person dies and has committed sins, that person can avoid burning eternally in hell if he takes the last Sacrament. One has to call for a priest, the person has to confess all his sins without omission, and afterward he can eat the Communion. Maybe he cannot go to heaven right away, but instead will have to go to purgatory. It is a sort of an antechamber of hell. People suffer and burn, but they can get out after their sins have been purged. This time can be shortened if the family asks the priest to say Masses. The family has to make sacrifices and prayers for the dead.”

The night was terrible. I saw Frida in the flames, the lady with her burst tummy moaning. The firemen had tails like the Devil, their faces were fire-red, and the twins were drowning in a river of fire. The saints didn’t hear my prayers because of the roaring fire. I screamed and woke up. Mother was sitting on the edge of my bed, wiping the sweat off my forehead. My bed was a snarled mess of covers. Mum tucked me in again and kissed me. I fell asleep, but a similar dream haunted me. The following evening I didn’t want to go to bed. My bed had become hell.

Zita’s head went back to normal again. She had given birth to puppies! Soon after, on one sunny day, my fancy lady passed by pushing a baby carriage. She, too, had shrunk. Running to Mum I asked her, “Do mothers carry their babies in their tummies like Zita?” Mother’s answer made liars out of Mrs. Huber and Aline!

“But why do people say I should put sugar for the stork in order to get a sister?”

“That’s a story for little ones!”

Again, for little ones! I’m not a little one. “Why, Mum, why do adults lie?” I got no answer.

“Didn’t God say ‘You shall not lie?’ Aren’t they afraid to go to hell?”

That night, while under my covers, I decided to avoid Mrs. Huber. I was not going to talk to her anymore. But why didn’t Mother answer my question? Why do grown-ups lie to children? I would have to beware of them! That put me in a very bad mood.

Dad was a wonderful playmate—always encouraging me to try new things. I had some trouble with the spinning top Uncle Germain had made for me. It turned, slowed down, wobbled, and fell motionless. To get it started again I had to wind the string around it, put the point on a level place, and swiftly jerk the string to liberate it.

“Keep trying. You’ll do better next time,” Dad said from the balcony, where he stood watching me. No cars came down our block; I had the whole street to myself. Some of our neighbors, who spent their summer evenings leaning on cushions and looking out the window, kept on teasing me. They made me even more determined. But it was time for me to go to bed, even though the sun had not yet set. It was so hot that Mum had decided not to close my shutters completely.

“Mum! Dad! Hurry, help, help! There is fire everywhere!” A strong orange-red light had enveloped my room. Dad took me from my bed and brought me to the balcony. Mrs. Huber, Mrs. Beringer, Mrs. Eguemann—everyone had come outside to look at the spectacular light show. The sun had set, the blue line of the mountain had turned black, the sky was fire red, and, downstairs, our teenage neighbor John played the blues on his mandolin.

“Who opened the door to hell?”

“This is not hellfire. It’s a spectacular sunset!”

“But only a giant fire could send so much red light into the sky!”

Mum and Dad looked at each other and shook their heads.

“I know for sure it’s hell because the priest said that a person either goes down to hell or up to heaven,” I insisted.

Dad explained something about fire and lava inside the earth, convincing me about hell even more and making me even more terrified. Mother brought me back to bed. Sitting with me, she told me once more that it wasn’t hell; it was the sun.

“Don’t be so scared about hell. We have the saints to pray for us, and we have a guardian angel.”

It didn’t help because I knew how terrible it is to die unprepared.

How awful, how terrible if my parents would die during the night! Every night I would sneak into their bedroom and put my finger under their noses to find out if they were breathing. Only then could I go to sleep!

One Sunday, as usual, the three of us went for our afternoon walk. It brought us near a tavern with a garden. I remembered being there when I was about three years old. I had danced on a tabletop and the customers had applauded. Dad recalled my performance, too, and he said sternly, “Remember this place? Let it be said, I do not want you to become a show girl!”

Really! It wasn’t necessary for him to remind me. I was now a serious girl—nearly seven years old! I know about sickness, death, purgatory, hell, and God sending all kinds of situations to test us. My parents tried to cheer me up, but my innocent childhood free of sorrow was gone. My religious education at school taught me how painful life on this earth can be and what effort one has to go through to become a saint. That had become my chief concern.

One year of intense religious instruction had propelled me into a state of permanent fear, fear of God—the Father who was so severe, so exacting. I really had no desire to dance—how could I?

Sitting on a little footstool, I was holding class for Claudine, trying to teach her the pronunciation of the German alphabet. Mother was waxing the shared wooden stairs outside our apartment; it was her turn to clean them. She was always unhappy because our neighbor only used water to wash them down, while Mum believed in shiny wooden steps. I heard her talking to someone in the hallway; suddenly she came in to get something and went back out.

“I’ll read them,” I heard Mum say. “I believe our God is sleeping and doesn’t see what is going on. I wonder what you have to say.”[4] I couldn’t imagine why Mother would say something like that! Will she go to hell? I knelt down in front of my altar, begging the saints to ask God not to be angry with her! I was afraid for her soul!

That same day it was my turn to wash the dishes, but I just couldn’t scrub the burnt food off the bottom of the pans.

“We will put some water in them and soak them; it will come off easier later on,” Mum said absently. She put the pans on top of a shelf on the balcony, just behind a blind she had installed to keep people from gazing into our kitchen. For days, the pots remained there!

Mum was enthusiastic about the booklets she had gotten. She went to the bookstore to get a Bible. Day after day she would read and read and read—she barely cooked anymore. Ever since the day she had forbidden me to go to church alone, she hadn’t returned to our church for confession and communion. She started going to another Catholic church nearby. But, after a while, she decided that she wouldn’t attend Mass anymore. So Dad and I went together. He seemed really down, and I felt uncomfortable, too. Even the beautiful organ music didn’t make me feel better.

My mother also forgot how to cook. She reads too much, I said to myself.

One night as I was lying in bed, I could hear my parents’ voices. I stretched my neck and tried to listen in. I was convinced they had a secret I was not supposed to know. I had to discover it. Creeping alongside the wall, I tried to hear what they were talking about. Father’s voice was insistent; Mother’s was very firm, but in an undertone she said something about being free to worship according to conscience.

“We are Catholics!” Dad kept repeating.

“We all know that! What is Dad thinking?” I wondered. Mother’s answer was inaudible.

Dad got really irritated and insisted, “We have to stay faithful,” and he added something about a rock in Rome called Peter and the pope who sits upon it. All of a sudden Dad stood up. I quickly turned to hustle back to bed, but it was too late. He saw me. As he came out of the salon, disgusted, he said to Mother, “Do what you want!” He continued to walk away, then suddenly turned to Mum and added in an emphatic tone, “I forbid you to talk about your ideas and your readings to Simone!”

I was ignored, left out, treated like a baby! I felt like I would burst from anger. I was so mad at Dad. I was determined to resist.

“Mum, what do you read every day?” I asked her first thing the next morning.

“Bible literature.”

“What’s that?”

“The Bible is the Word of God.”

“I’ll read it too.”

“Later.”

“No, right now.”

“Simone, I promised your dad that I wouldn’t share a Protestant Bible or any literature with you.” I knew they were keeping something from me!

“But Dad isn’t here!”

“Yes, but I promised him.”

“Dad won’t see you, and I won’t tell him!”

“That would not be right; it would be lying. Child, your father is working hard to feed us and to pay the house rent. He has the right to make decisions concerning your education.” Inside I was burning up.

“But why? Why can’t I read what I want?”

A strange atmosphere had crept into our home. Mother still didn’t go to church, but at least she didn’t burn the food anymore. Father didn’t talk anymore, not even about socialism! His greetings to Mother were mechanical—no warmth, no enthusiasm, only questionings.

“Who have you seen? Where have you been going?” What foolish questions! Father knows that she sees only the grocer, the butcher, and the baker. Why does he bother her like that? But one time his questioning got worse.

“Do you mean the men who gave you those booklets didn’t come back?”

“No, and I feel bad about it. I have so many questions I want to ask them.” Dad didn’t like this either. They were so absorbed in their conversation they didn’t notice me. He kept on.

“Who brought you those other brochures?”

“I ordered them,” and nervously Mum pulled out a brown paper with stamps. “Here is the proof,” she said with annoyance.

“Why did you order so many, and where are they all?”

“I ordered three kinds. They sent me ten of each.”

“And what did you do with them?”

“I shared them with our neighbors in the apartment and down the street.” Dad shook his head angrily.

Sneaking farther back in the corner of the room, I said to myself, Dad has forgotten that I’m here. I’ll try to keep quiet.

He looked straight into Mum’s eyes and said, accentuating each word, “Are you spreading propaganda now?” Mother turned pale. Would she fight back? I would have! Dad was treating her like a child.

After a while she said, “Adolphe, people have the same right that each one of us has—the right to choose. But to do so, they have to have a choice; this is not propaganda.”

I thought, “Well done, Mum!” And without realizing it, I spoke up, murmuring that people have the right to read what they want, and I did too! Turning to gaze at me, both of them fell silent.