Читать книгу Unjustifiable Risk? - Simon Thompson - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

INTRODUCTION

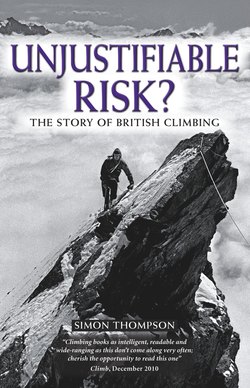

To the impartial observer, Britain does not appear to have any mountains. Yet the British invented the sport of mountain climbing, and for two periods in history, in the second half of the nineteenth century and for a shorter period in the second half of the twentieth century, they led the world. In no other comparably flat country have mountains and climbing played such a significant role in the development of the national psyche, both reflecting and influencing changing attitudes to nature and beauty, heroism and death. This book is about the social, cultural and economic conditions that gave rise to the sport in Britain, and the achievements and motives of the individual scientists and poets, parsons and anarchists, villains and judges, ascetics and drunks who have shaped it over the past 200 years.

Like all sports, climbing is the pursuit of a useless objective – the summit of a mountain or the top of a cliff – for amusement, diversion or fun, and in common with most other sports with a strong amateur tradition the means are more important than the end, but not by as much as some climbers like to pretend. Unlike most games, but in common with other field sports, climbing has no written rules. Instead there is an ever-evolving set of unwritten but widely accepted conventions that govern its conduct. The only sanction if you break these ‘rules’ is the disapproval of your peer group. As Colonel Edward Strutt, Alpine Club grandee and self-appointed guardian of British climbing morality in the 1930s, observed: ‘The hand that would drive a piton into British rock would shoot a fox or net a salmon.’1 In most sports it is easy to define what ‘winning’ means, but not in climbing. In the early days, success meant reaching the summit of an unclimbed peak, but mountaineering was never simply exploration in high places. People with truly exploratory instincts soon became bored spending months trying to climb a single mountain (even if it was Everest) when the whole of the Himalaya lay around them, untravelled and unknown. The conquest of a virgin peak remains the ultimate ambition for some climbers today, but as the supply of readily accessible unclimbed mountains began to dwindle, winning was gradually redefined. In the mid-1890s, Fred Mummery, the leading climber of the day, wrote that ‘the essence of the sport lies not in ascending a peak, but in struggling with and overcoming difficulties’.2

Over time, with improving technique and rising standards, it became clear that almost any rock face or ice wall could be climbed, given enough manpower and equipment, and the style of the ascent became paramount. The most dangerous and therefore the ‘best’ style is to climb a route alone (‘solo’), without a rope. The worst is to drill holes in the rock and use expansion bolts to create a line of fixed ropes running from the bottom to the top. Between these two extremes lie an almost infinite variety of styles, the nuances of which confuse all but the most devoted practitioners of the sport. Climbers have always soloed short, easy routes on sunny days. Progressively the same approach was applied to longer, harder climbs, to alpine peaks and finally to the highest peaks of the Himalaya.

As with every sport, a large part of the attraction lies in the uncertainty of the outcome, but in climbing the consequences of failure can be fatal. Bill Shankly, the manager of Liverpool Football Club, once quipped that football ‘isn’t a matter of life and death, it’s more important than that’. For elite climbers, this really is true. Overall, climbing is not a particularly dangerous sport – the risk of harm is more often imagined than real – but the sensation of fear is intensely real and that feeling either attracts or repels. For some it becomes almost an addiction. At the leading edge, the objective of the sport is to take risks that others consider unjustifiable, and within the small community of top climbers everyone knows a dozen or more people who have died in the mountains, and yet they continue to climb. Extreme climbing is the ultimate expression of ‘deep play’, Jeremy Bentham’s term for an activity where the stakes are so high that the potential for loss far outweighs the potential for gain. From a utilitarian standpoint, it is clearly an irrational activity, but climbing is a sport for romantics, not rationalists, and climbers are drawn to risk like moths to a flame. The typical weekend climber eases himself cautiously forwards, pulling back the instant he feels the heat, but the frisson of fear is sufficient to sustain his heroic self-image through another mundane working week. The elite climber flies ever closer to the flame and plays ‘this game of ghosts’ for real.

Almost regardless of their absolute level of achievement, when climbers operate at their personal limit they experience an emotional intensity, both elation and despondency, that exceeds all but the most ecstatic and traumatic events in ordinary life. During a climb all mental noise, all distractions, are eliminated and the mind focuses solely on the flow of climbing. For a short period of time all of the cares and concerns of the world disappear and all that is left is the climber and the mountain. The experience is so vivid and taut that ordinary life can feel grey and flaccid in comparison. For elite climbers, ‘deep play’ is rational because a man who is afraid to die is afraid to live.

But there is more to climbing than pure heroics. It is possible to climb in a disused quarry full of rusting cars and stagnant pools or on a specially constructed wall in the middle of an industrial estate, but for the majority of climbers the beauty and grandeur of the surroundings are an intrinsic part of the sport. Mountains have always been regarded as spiritual places, and for the past 200 years they have also been regarded as beautiful, a refuge from the polluted and crowded complexity of the urban environment where most climbers are born and bred. Like ballet or gymnastics, the beauty of climbing also lies in movement. A mountain path is a physical manifestation of the aesthetic urge to see the view from the ridge and the next horizon, and there is beauty in the line of ascent, even individual moves, on the chosen mountain or crag. The most elegant ‘classic’ lines tend to follow distinctive natural rock features in grand surroundings, with an ever increasing sense of height and exposure as the route is ascended. Classic routes must present a significant climbing challenge and demand a variety of techniques, but they are often the easiest line of ascent of a particular rock face or mountain, so that escape to an easier route is impossible and the choice is either to go up or to retreat. Above all, classic routes have a history. Climbing is a human activity, and a rock without a history is just a rock.

The shared experience of hardship and danger on a climb can be the basis of the strongest friendships, but climbing is essentially a solitary sport and there are few more lonely situations (voluntarily entered into) than leading a long pitch at the absolute limit of your ability. While the activity itself tends to be solitary, the climbing community is gregarious and tribal. Perhaps because of the collective release of nervous tension, climbers are known for their excesses when they return to the valleys and the sport has a well-deserved reputation for wild and reckless behaviour. This strange and contradictory mixture of ingredients – heroic and aesthetic, gregarious and solitary, self-disciplined and reckless, ascetic and debauched – has attracted an equally strange and eclectic mixture of people to the sport. It has also created tensions between those whose motives are primarily heroic – the vigorous pursuit of liberty, adventure and self-fulfilment – and those whose motives are primarily aesthetic – concerned with man’s emotional response to the mountain landscape.

Much has changed in the climbing world since its beginnings in the nineteenth century, but even more has remained the same. In many respects British climbers of today would be instantly recognisable to their Victorian predecessors, with their desire for adventure, love of wild places and need to escape from ‘civilised’ society. But the sport has also evolved, reflecting changes in British society, from a pastime undertaken by an eccentric and privileged minority to a part of the mainstream leisure and tourist industry. Society’s attitude to climbing and to climbers has also changed. When British climbers first ‘conquered’ the Alps in the mid-Victorian era, the sport was regarded with mildly disapproving incomprehension, that men should risk their lives for such a useless ambition. By late Victorian and Edwardian times, as they extended their activities to almost every corner of the globe, climbers came to be seen as plucky heroes whose achievements underscored Britain’s right to rule a quarter of the world. In the aftermath of the First World War, the disappearance of Mallory and Irvine, enveloped by clouds as they tried to reach the highest point on earth, had an almost redemptive quality after the mechanised mass slaughter of the trenches. When Hillary and Tenzing finally reached the summit of Everest after the Second World War, even though neither of them was British, they were part of a proudly nationalistic project, marking the end of Empire but heralding the dawn of the New Elizabethan Age. As climbing has progressively become a mass activity in the post-war years, the heroic status of climbers has come under increasing scrutiny. In the secular twenty-first century, the British like their heroes to be banal celebrities or saintly figures who combine benevolence with bravery. Most top climbers are neither banal nor benevolent, but they are brave. They deliberately set out to do things that no-one has attempted to do before: things that most normal, rational people would find quite terrifying. Yet the motives and desires of elite climbers, as they grapple with their icy peaks, are not so very different from those of the 4 million ordinary climbers and hill walkers active in Britain today, and it is partly this sense of recognition and shared experience that makes the lives of these flawed heroes so compelling.

I first started rock climbing in the long, hot summer of 1975. Within a week I seconded an HVS in hiking boots and by the end of the summer I was leading VS (see Appendix I for an explanation of climbing grades and Appendix II for a glossary of climbing terms). I was completely obsessed by the sport and flattered myself that I had the makings of a good climber. By the end of the 1970s, as climbing standards continued to rise inexorably while my own energies and enthusiasms were increasingly directed elsewhere, I concluded that I was probably an average sort of climber. By the mid-1980s it was obvious that even this was an exaggeration. With the benefit of 34 years of experience it is now clear that, in terms of technical difficulty, my rock climbing achievements reached their zenith about 30 years ago while my equally modest mountaineering achievements peaked about 15 years ago. Over the past 34 years many things have changed in my life, but the mountains have remained a constant. I have had good days and bad days at work, but I am hard pressed to think of a single climbing day that I have regretted, at least in retrospect. When I reached the age of 49, mindful of Don Whillans’ admonition that ‘by the time you’re 50, you’re completely fucked’, I decided to write this book before it was too late. The decision reflects my continuing fascination with this strange sport.

Given my lack of accomplishment as a climber, some readers may question whether I am qualified to write a history of the sport. I would contend that the best climbers do not necessarily make the best historians, since so many of them appear to agree with Winston Churchill that ‘history will be kind to me, for I intend to write it’. Donald Robertson, who died in a climbing accident in 1910, observed that a truly honest account of a climbing day has yet to be written, and it remains a truth almost universally acknowledged that there are only two approaches to writing about climbing: exaggeration or understatement. Since the activity necessarily takes place in inaccessible places with few impartial witnesses, the boundary between fact and fiction is often blurred, and climbing history is full of larger-than-life characters around whom myths have grown up that are certainly not literally true, but which may nevertheless provide a true insight into the nature of the climber, their deeds and the times in which they lived.

Gustave Flaubert compared writing history to drinking an ocean and pissing a cupful, and there can be few other sports that have given rise to a body of literature as rich, varied and, above all, extensive as climbing. Having drunk at least part of the ocean, the challenge is to decide what should go into the cup. Inevitably, this particular version of climbing history reflects my own interests and prejudices, and no doubt contains both omissions and inaccuracies. But I hope that it also reflects the true spirit and tradition of the sport which is, first and foremost, about the pure joy of climbing.