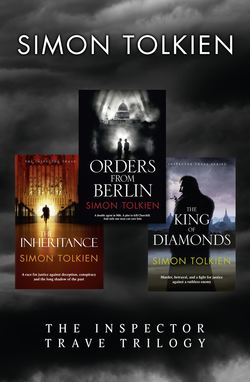

Читать книгу Simon Tolkien Inspector Trave Trilogy: Orders From Berlin, The Inheritance, The King of Diamonds - Simon Tolkien - Страница 19

CHAPTER 6

ОглавлениеThe next morning, Seaforth was waiting for Ava on the other side of the street from her flat when she went out to do her shopping. She was shocked and even a little alarmed to see him. It made no sense that this complete stranger was suddenly so interested in her, unless it had something to do with her father’s death. Anyone could be the murderer. It could be Bertram; it could be this man, except that he didn’t feel like a killer to her – which was a stupid way to think, she told herself. Seaforth’s sparkling blue eyes, which seemed to promise humour, tenderness, and understanding all at the same time – everything that had been missing from her life up to now – had nothing to do with it. She needed to watch herself, to stay on her guard. Now more than ever.

‘I’m sorry to show up like this. Unannounced, I mean,’ he said, falling into step beside her as she walked towards the bus stop. ‘I got your address from the phone book. I wanted to see you – to apologize.’

‘Apologize?’ she repeated, surprised. ‘Apologize for what?’

‘For what happened with Alec Thorn yesterday. It was inappropriate; it should never have happened.’

‘It wasn’t your fault. Alec attacked you, not the other way round. I can’t imagine why. I’ve never seen him do anything like that before.’

‘He’s changed.’

‘Changed?’

‘Yes, it’s the war. When did you last see him?’

‘A few months ago, maybe more. I’m not sure.’

‘Months are a long time nowadays. They seem like years. We’re under a lot of pressure at work, and Alec feels it more than most – perhaps because he’s a bit older than the rest of us. He’s closer to your father’s generation than to mine.’

‘Us! Who are us?’ she asked, stopping and turning to face her companion. ‘Please tell me, Mr Seaforth. I need to know.’

‘Charles,’ he said, meeting her gaze. ‘You must call me Charles.’

‘Charles, then,’ she said, sounding the name on her tongue, liking it, feeling it fit. There was no place for caution if this stranger could tell her who her father was – as she’d said, she needed to know. ‘Can’t you help me?’ she asked, putting her hand on his arm. ‘No one else will. I feel like I said goodbye to a stranger yesterday, not my father.’

Seaforth said nothing, so she guessed. ‘It’s the Secret Service,’ she said. ‘You’re spies. That’s what you are, aren’t you?’ It was framed as a question, but she didn’t need an answer. As soon as the words had left her mouth, she’d known she was right. It was as though she’d known the truth for years but had never been prepared to admit it to herself until now.

‘We’re patriots,’ Seaforth said quietly. ‘That’s all. Everyone does their part in different ways.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Yes, I can understand that.’

‘You can’t tell anyone I told you. You know that, don’t you?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Don’t worry, I won’t.’

The first emotion she’d felt was relief. At least there had been a reason for her father’s silence; at least he’d done something worthwhile with his life. But now she felt something else – a surge of spontaneous gratitude towards Seaforth. He hadn’t told her the truth because he couldn’t, but he’d certainly enabled her to find it. He’d taken her seriously. Not like her father and Alec Thorn, shutting her out because she was a woman and couldn’t be trusted.

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘It helps to know.’

‘You have nothing to thank me for. I came here to apologize. Remember?’

‘Yes,’ she said, smiling. ‘I remember.’ She relaxed for a moment, but then her nervous curiosity about the reasons for Seaforth’s interest in her returned, and with it a sense of unease. ‘Why does Alec hate you?’ she asked, remembering Alec’s unseemly rage outside the church and the effortless way that Seaforth had held Alec’s hand suspended in mid-air for a moment before he let go.

‘He thinks I want his job,’ Seaforth said carefully. It was as if he were measuring his words, working out how much he could say.

‘Do you?’

‘I want what’s best for the country.’ He smiled, noticing the frown on her face. ‘Sorry, that’s not good enough, I know. The fact is this is a young man’s war, and if we’re going to win it, a lot of the old guard will have to be swept away. Some of that happened after the last war, but not enough. It’s what works that matters now. There’s no place for a sense of entitlement when our backs are up against the wall. I think people like Alec Thorn find that hard to understand.’

‘Because he doesn’t want to be swept away?’

Seaforth nodded.

‘Like my father was?’

‘I told you at the funeral that your father was a great man. He could have accomplished great things, but no one would listen to him. He understood what was at stake with Germany when Hitler came to power, but everyone was obsessed with Joe Stalin and the Reds, and then it was too late. He was a voice crying in the wilderness.’

They walked on in silence until they reached the bus shelter, where Ava stopped, turning to look again at her companion. She sensed there was something else he wanted to say – something personal, nothing to do with Hitler and Communism. She could tell from the look of indecision on his face.

‘What is it, Charles?’ she asked. ‘There’s something else, isn’t there? What is it you want with me?’

‘I can’t tell you here,’ he said. ‘Could we meet sometime – somewhere we can talk?’

‘Why?’ she asked, taking a step back. ‘You need to tell me why.’

‘Because there are other things I’ve got to tell you, things you need to know – about your father, about his death. I only need a few minutes. It isn’t much to ask.’

A bus was coming, and she reached out her hand, hailing it to stop. She turned away from him, getting out her purse for the fare. ‘I don’t know,’ she said.

The bus came to a halt beside her and she took hold of the grab pole in her hand but didn’t mount the platform. She knew Seaforth was waiting for an answer, but she felt unable to respond – caught between curiosity and suspicion.

‘Please,’ he said. ‘You won’t regret it.’

‘The Lyons Corner House – the big one in the West End, by Piccadilly Circus,’ she said, saying the first place that came into her head. Only later did she realize its unsuitability – it was the same restaurant where Bertram had proposed to her over tea and cake three years before.

‘Come on, dearie, make up your mind. Are you getting on or are you getting off?’ asked the conductress impatiently. ‘We haven’t got all day.’

Ava stepped onto the platform and the conductress rang the bell. The bus moved off, away from the kerb.

‘When?’ asked Seaforth, shouting over the noise of the engine.

‘Tomorrow,’ she shouted back. ‘Twelve o’clock.’

Seaforth raised his hand as if in acknowledgement, but she didn’t know for sure whether he’d heard her. And as she sat down, it occurred to her that she didn’t even know whether she’d wanted him to.

She closed her eyes, and out of nowhere a memory rushed to meet her from the remote past. She was a small child in a snow-suit, standing with her father at the top of a steep hill. The world was white and he was bent over a wooden toboggan that he was holding in position a few inches back from the beginning of the slope. He was telling her to get in – she could hear his voice, and she could remember how his face was red in the cold – but she continued to hesitate, frightened that they would crash and that she would be smashed to pieces against the line of ice-laden birch trees that she could see in the valley below.

‘Are you coming or not?’ her father demanded, impatient just as the bus conductress had been a moment before. But try as she might, she couldn’t remember whether she had got in the toboggan and gone screaming down the hill or given in to her fears and slunk away. It was too long ago.

In the afternoon, Bertram got out the car and drove them over the river to Scotland Yard. The young policeman Trave had rung up in the morning to say that their statements were ready for them to read through and sign.

And then halfway down the Embankment, Bertram announced in a self-important voice that the next day at 12.30 had been fixed for the reading of her father’s will at the solicitor’s office – a champagne moment for him at which he wanted her present. Ava was taken aback. She’d been worrying all day that she had made a mistake agreeing to meet Seaforth in the West End, but it hadn’t occurred to her that the arrangement would cause her a problem with Bertram. He’d been out a lot in recent days, revelling in his new role as her father’s executor, and she’d thought it safe to assume that her absence from the flat for several hours in the middle of the day would go unnoticed.

Now, without warning, she was faced with a choice between lying to her husband and not going to her meeting with Seaforth. She had no means of contacting Seaforth to change the time, and she was sure he would assume that she’d decided not to see him if she didn’t show up. Moments before, she had been contemplating staying away, but she felt differently now that the decision was being forced on her. Talking to Seaforth for a few minutes had enabled her to find out more about her father than she had discovered in all the years he was alive, and Seaforth had told her at the bus stop that he had more to tell her. She didn’t trust Seaforth. How could she, when he had descended on her out of the blue without giving any adequate reason for his sudden interest? But she couldn’t give up on the chance to know more about her father, even if the price was lying – something she had always hated doing.

‘I can’t go,’ she said. ‘I’ve got plans.’

‘What plans?’ asked Bertram, sounding annoyed. ‘What are you doing?’ He seemed surprised that she should be doing anything, which spoke volumes, she thought, about what he thought her life was worth.

‘I’m seeing someone at twelve o’clock for lunch – my mother’s cousin. She was at the funeral,’ Ava lied, naming the first person who came into her head. But it was a bad choice.

‘Do you mean Mrs Willoughby?’ asked Bertram. ‘I thought she was only up in London for the day.’

‘No, she said she was staying on. And I’ve got no way of getting in touch with her to rearrange, so you’ll have to change the time with the solicitor. I can go later in the afternoon if you like.’

‘No, we’ll go in the morning. Mr Parker offered me an earlier time when we spoke, but I thought twelve would be better. I should have talked to you first, I suppose,’ he said grudgingly.

Ava breathed a sigh of relief. She’d got what she wanted, but she knew that the lie had moved her into uncharted territory. Before it, she could tell herself that there was nothing improper in seeing Seaforth, as he had important information to give her. Now it felt as if she were committing herself to something irretrievable – an act of betrayal.

At the police station, they were put into separate rooms and seen by separate policemen. Trave saw Ava. He waited, watching her carefully while she read through her statement. He sensed the tension in her. It was as if she were coiled up, hiding inside an inadequate shell, trying not to be noticed. But then when she glanced up from her reading, the flash of her bright green eyes made her seem an entirely different person – vivid and alive.

‘How have you been?’ he asked when she’d finished signing.

‘Surviving,’ she said with a wry smile, touched by the genuine concern in his voice. ‘The funeral wasn’t easy, but you had a ringside seat for that.’

‘I’m sorry. I should have told you I was coming,’ he said, looking embarrassed. ‘My inspector sent me. It’s standard procedure in these cases.’

‘Don’t worry – the more the merrier,’ she said with grim humour. ‘I’m just glad it’s over.’

‘I can understand that,’ said Trave, nodding. ‘Who was the man arguing with Mr Thorn? Do you know him?’

‘No, that was the first time I’d met him. His name’s Charles Seaforth. He worked with my father.’

‘And Mr Thorn and he don’t get on?’

‘No, apparently not,’ said Ava. She looked for a moment as if she were about to say more, but then she lowered her eyes. Part of her wanted to tell Trave about her encounter with Seaforth earlier in the day, but she resisted the temptation. It wasn’t as though she knew anything about the murder that the police didn’t, or at least not yet. And she felt obscurely that she wouldn’t be able to go through with her meeting with Seaforth the next day if it became public knowledge. She wanted to hear what he had to say. Afterwards she could decide what she should do with the information.

‘Have you seen this before?’ asked Trave, taking out a plastic evidence bag and laying it on the table between them. It contained a single black cuff link with a small gold crown embossed in the centre.

Ava looked at it carefully and then shook her head. ‘I don’t recognize it,’ she said. ‘Where’s it from?’

‘We found it on the landing outside your father’s flat, close to where he must have been struggling before he fell. It had rolled into a corner.’

‘Well, it could have been his, I suppose. My father liked his ties and cuff links, just like my husband. I wouldn’t necessarily recognize every one he had.’

‘We don’t think it was your father’s,’ Trave said quietly. ‘We’ve been through all his belongings and there’s no other cuff link that matches this one.’

‘So you think it belonged to the man who killed him – that my father tore it from his attacker’s sleeve while they were struggling?’ said Ava, looking back down at the cuff link with fascination. It seemed strange that something so small could become so significant.

‘Quite possibly,’ said Trave, watching Ava closely. ‘You mentioned that your husband likes cuff links. Could this be one of his?’

‘I don’t know. Maybe. Is Bertie a suspect? Is that what you’re saying?’ Ava’s voice rose in sudden panic and she gripped the edge of the table.

Instinctively, Trave leant forward and put his hand over Ava’s for a moment, trying to reassure her. ‘I know this is difficult, but please try to stay calm,’ he said. ‘We’re looking at every possibility because that’s our job. As soon as we have some news, you’ll be the first to know.’

Ava nodded, visibly trying to control her anxiety.

‘But in the meantime, I think it would be best if we kept this evidence between ourselves …’

‘Don’t tell Bertie, you mean?’

‘Yes, if you don’t mind.’

‘All right, but Mr Trave …’

‘Yes?’

‘Please get this right. Find the man who killed my father – the right man, so you’re sure. Promise me you won’t leave any stone unturned.’

Ava looked at Trave hard, waiting with her green eyes fixed on his until he nodded his assent.

‘Well, did she recognize it?’ asked Quaid when Trave returned to their shared office after showing Ava and Bertram out.

Trave shook his head.

‘Pity,’ said Quaid. ‘But I’d still bet my bottom dollar it’s his. Do you think she’ll tell him about it?’

‘She said she wouldn’t.’

‘And did you believe her?’

‘Yes, I think so.’

‘Well, it probably won’t make any difference one way or the other. We’ll see if we can dig up anything more on our friend the medicine man, tomorrow, and then, whatever happens, I’ll apply for a search warrant and we can find out what he’s got hidden away. I reckon we’ll find a lot more than just the matching cuff link.’

‘So you’re sure he’s guilty?’

‘Yes, have been from the moment I clapped eyes on him. I’ve got a nose for criminals, remember? And murderers are my speciality.’

‘But don’t you think we should look at other possibilities, even if just to eliminate them?’

‘Like what?’

‘Well, did you find out anything about what happens at that place where Morrison used to work – 59 Broadway?’

‘Yes, as a matter of fact, I did. It’s exactly as I thought – the building’s a department of the War Office and the people there don’t need us poking our noses in where we’re not wanted.’

‘You were told to stay away?’

‘No, of course I wasn’t,’ said Quaid irritably. ‘I’ve got the right to take a search team into Buckingham Palace if that’s what a case requires, but this one doesn’t. We don’t need to complicate the investigation just for the sake of it, not when we’ve got the murderer staring us in the face. I’ve already told you that.’

‘Do you know who you spoke to?’ asked Trave, refusing to be put off. There was something terrier-like about his persistence.

‘It’s none of your business. And I don’t want to hear any more of your damn fool questions about the place,’ said Quaid, getting visibly annoyed. ‘You’re to stay away from St James’s Park, do you hear me? And concentrate on Bertram Brive. He’s the culprit and we need to bring him in – the sooner the better. I’m in court tomorrow morning, but we can catch up when I get back.’

All things being equal, Trave would have preferred not to cross his boss, but he felt he had no choice about going back to Broadway. There were too many unanswered questions associated with the place. Why had Albert Morrison rushed over there on the day of his death? And why was there no record of his visit? Was it because he had been intercepted? And if so, by whom?

Albert had worked at Number 59 until he retired. Thorn worked there still, and according to Ava, so did the man Seaforth, whom Thorn had attacked at the funeral. What was it that they were all doing inside the building with the flat, featureless façade and the blacked-out windows? And why had Thorn lied to him about the purpose of his visit to Albert’s flat and the note he had left with Mrs Graves? Because he had lied – Trave was sure of it. Just as he was sure that someone associated with Broadway had got to Quaid and told the inspector to call off the dogs. Why? It had to be because someone there had something to hide. But who? And what?

Questions leading to more questions – Trave felt as if he were in a blindfold, groping around in the dark, and he knew that the only way he was going to get answers was to find them out on his own. He remembered the dead man lying broken like a puppet on the hall floor at Gloucester Mansions and the promise he’d made to Ava to find the man responsible for putting him there. He couldn’t honour it without going back to Broadway, so first thing the next morning he took the Tube to St James’s Park and stationed himself behind a cup of coffee and a copy of The Times in a café diagonally across from Number 59 with a grandstand view of the front door.

Between half past eight and nine, a succession of furtive-looking people went into the building, starting with Jarvis, the ancient doorman–caretaker in grey overalls whom Trave had encountered on his first visit. Thorn arrived on the stroke of nine, head bowed and back bent and with the smoke from his cigarette blowing away behind him down the street each time he exhaled. Such a contrast to Seaforth, who showed up soon afterwards, strolling down the pavement as if he hadn’t got a care in the world.

And then nothing for over two hours. Trave was sleepy and several times caught himself starting to nod off with his newspaper slipping from his grasp. The Luftwaffe seemed to have selected the streets around the rooming house where he lived in Fulham for special treatment the previous night, and he’d been up through the small hours helping to fight incendiary fires in neighbouring buildings with sand and stirrup pumps. He’d managed to snatch a couple of hours’ sleep after the all clear, and his body was crying out for more.

He was almost on the point of giving up and returning to Scotland Yard when the door of Number 59 opened and Seaforth emerged. He stood on the pavement, putting on his hat and gloves, and then walked away to his left. His lips were pursed and it looked as though he were whistling a tune. Trave waited until he had gone past and then followed him into the Underground station at the end of the street.