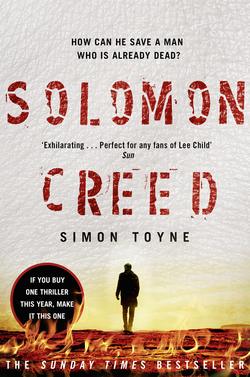

Читать книгу Solomon Creed: The only thriller you need to read this year - Simon Toyne, Simon Toyne - Страница 29

19

ОглавлениеThe ambulance screamed to a halt in the shade of the billboard and medics and doctors swarmed around it. Everyone else stood back, grimly fascinated by what would emerge from inside and frightened at the same time.

Solomon knew what was coming. The strangely familiar smell of charred flesh had already told him. It warned him exactly how bad it was going to be too. The siren cut out and was replaced by a howl that came from inside the ambulance.

‘Here –’ Billy Walker appeared at his side and handed Solomon a starter cap, his attention fixed on the ambulance. ‘Best I could do. Got you some boots too.’

‘Thank you.’ Solomon took them and inspected the cap. It had a red flower logo and the name of a weedkiller on it. He pulled it over his head, folding the peak round with his hands until he was looking at the ambulance through an arc of shadow.

‘You should use this too –’ Walker handed him a tube of heavy-duty sunscreen squeezed almost empty.

The howl doubled in volume with the opening doors and there was a clatter of tubular steel as a man, or what remained of one, was pulled from the ambulance. He lay twisted and charred on starched white sheets, his whole body shaking, his hands baked to talons by furnace heat and clawing at the smoke-filled air above him while the inhuman noise howled from the seared ruin of his throat.

‘Jesus,’ Walker said, his voice flat with horror. ‘I think that’s Bobby Gallagher. He was driving the grader.’ The medics wheeled the gurney to a covered area and doctors clustered round him. ‘You reckon they can save him?’

Solomon squeezed sunblock from the tube and rubbed some on to his neck and the back of his hands, disliking the greasy feel of it but disliking the growing itch of sunburn even more. ‘Not a chance,’ he said.

Bobby Gallagher stared up at the ring of faces crowding over him. Worried eyes stared down.

A doctor leaned in, his face filling his vision. His mouth was moving but he couldn’t hear what he was saying. Too much noise. Someone screaming close by. Someone in pain. At least he didn’t feel nuthin’. That was good, wasn’t it? Surely that was a good thing.

A penlight snapped on, shining in his eye and making the world turn bright and milky, like everyone was wrapped in white smoke … smoke …

The fire …

He had seen the flames curling towards him, the desert writhing in heat like the surface of the sun. The fire running alongside him, chased by the wind, leaping from shrub to shrub like a living thing. Never seen fire race so fast, faster than that old grader, that was for sure, but not as fast as that Dodge he’d had his eye on, the silver-grey one with the smoked windows and the V8 under the hood. That would have evened the race out some. Would have bought it too, taken the hit on the finance and all, if he hadn’t been saving for something else. He wanted to see old man Tucker’s face at summer’s end when he cashed in all the extra shift hours he was pulling and slipped that big ole ring on to Ellie’s finger. Eighteen-carat yellow-gold band with a one-carat, heart-cut diamond right in the centre: three and a half grand cold, every cent he had in the world and all of it for Ellie – fuck old man Tucker, the way he treated him, like he wasn’t good enough to even speak his daughter’s name.

The penlight snapped off and the doctor leaned in, his mouth moving again, everything slow like he was underwater. Still couldn’t hear a damn thing, what with that howling. He’d heard something like it before and the memory of it needled into making him shake with more than cold.

When he was eight his daddy had taken him hunting. They’d tracked a big old mule deer out into the desert for almost three hours and when they caught up with it his daddy had handed him the rifle. It was that old Remington, the one that hung above the fire with the walnut stock worn smooth at the neck by the bristled cheeks of his daddy and his daddy before that: beautiful rifle, but heavy, and tight on the trigger.

Maybe it had been the weight of it or the excitement of being handed something he’d only ever seen in a man’s hand before, but when he beaded up on that big old bull his heart had pounded so hard he felt sure the deer must be able to hear it even with him two hundred yards away. It had lifted its head and sniffed the air, its haunches tightening as it readied to run. He snatched the shot just as it moved, missed the heart and punched a hole right through its belly. Gut shot or not, that thing took off, blood pumping out all over the desert, innards flyin’ out behind it like streamers. His daddy said nothing, just grabbed that rifle back and took off after it, carrying it as easy in his hand as it had sat so heavy in his.

The blood trail was wet and bright against the dry orange earth. And the deer howled as it ran, a great bellowing noise, like fury and pain mixed together. Ever after, when he sat on the hard wooden pews in the cool dark of the church and heard the reverend deliver his ‘hell and damnation’ sermons he would remember that noise. It was like he imagined hell must sound, the echoing tormented howl of a soul trapped deep underground – the same thing he was hearing now.

The doctor leaned in again, swimming down through the milky air. He still couldn’t catch what he was saying. He tried to tell him he couldn’t hear above the howling, managed to snatch a ragged breath and the noise stopped. He made to speak and it started up again even louder than before, so loud he could feel it deep within his chest. Then he realized where the sound was coming from, and began to cry.

They had caught up with the deer not so far up the track from where he’d shot it, down on its front knees like it was praying. He wanted to shoot it and put it out of its pain, but his daddy had the gun and he daren’t ask him for it. They stood a ways back, watching it trying to get up and run, eyes rolling in its skull, and that awful sound coming out of it. He had turned to look away but his daddy put his hand on the top of his head and twisted it back round again.

You need to watch this, he’d said. You need to watch this and remember. This is what happens when you don’t do a thing right. This is what happens when you fuck somethin’ up.

The jolt of him cussing like that, his best-suit-on-a-Sunday daddy who he’d never even heard say ‘damn’ before that day had been more shocking than the sight of the dying deer or the noise it made while it was about it.

I’m sorry, Daddy, he whispered now, and the faces moved closer as the howl took the rough form of his words.

I think he’s calling for his daddy, the doctor said.

Bobby, we’re doing everything we can for you, OK? Just hang in there.

He had been trying to steer away from the fire but the damn grader could only run over the flat land and the contours had kept him too close. He’d seen a place to turn ahead of him and he’d kept his eyes focused on it, too focused to notice the wall of flame sweeping in from his left. He could have jumped and run but he didn’t. He knew they needed the grader to draw the fire line and help save the town. Might be old man Tucker would show him some respect if he came out of this a hero.

The heat had closed round him like a fist, the skin on his knuckles bubbling where they curled around the wheel. He’d kept his eyes ahead of him and his foot on the gas, holding his breath like he was deep underwater and kicking for the surface. He’d known that if he breathed in, the flames would get inside him and he would drown in that fire, so he had held on, thoughts of Ellie and diamond rings running through his head until he reached the turn and steered the grader away and out of the fire. He didn’t remember much else.

He looked up into the doctor’s face now and realized that the fact he could feel no pain was actually a very bad thing. He didn’t care for himself. It was Ellie he felt bad for. Maybe old man Tucker was right, maybe she was better off without him. He had spent his life running away from that sound, the sound of failure and pain, and now it was coming out of him.

I’m sorry, he said, I messed up. I messed it all up.

Then the pale man stepped into view.