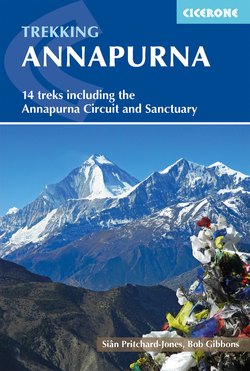

Читать книгу Annapurna - Siân Pritchard-Jones - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The power of such a mountain is so great and yet so subtle that, without compulsion, people are drawn to it from near and far, as if by the force of some invisible magnet…

The Way of the White Clouds, Lama Anagarika Govinda

Misty moods: Dhaulagiri from Kopra (Trek 4)

First used in our Cicerone Mount Kailash trekking guide, this quotation is surely no less apt when applied to the Annapurnas. Of all the great Himalayan peaks, the Annapurnas are unique. They are not defined by a single soaring summit, but comprise a vast massif, encompassing multiple peaks, spires and impossibly high ridges. The whole range is about 60km in length, with four major peaks and many subsidiary summits. Even the most sedentary soul will wish to get closer, to explore the verdant valleys, discover the mysterious gorges and head for the high passes.

Trekkers come from far and wide to discover Annapurna. Many arrive full of barely controlled anticipation, seeking a new challenge. All will leave with a renewed inspiration for life – there is something truly uplifting about being among some of nature’s most magical arenas. Everyone will lament the poverty of the ‘developing’ world, but look deeper – do you see many unhappy faces? Nepal’s people are her greatest asset: hard-working, brimming with almost child-like humour, boisterous, endearing, versatile and hungry for change, just like most people across our planet.

Any journey in and around these mountains is a joy, with experiences to treasure for a lifetime. Routes lead around tranquil lakes, through rich farming country, forests of bamboo and rhododendron, cool rainforest, silent alpine glades and rugged, high mountain desert. In the villages, excitable children rush to practise their English. Elsewhere a Hindu god may catch your gaze, or you may hear the chanting of monks in a monastery clinging to a strangely eroded cliff. The Annapurnas may dominate the landscape, but the people and the culture will surprise and delight in equal measure.

This latest Cicerone guide to Annapurna discusses the impact of new mountain ‘roads’ on the trails. Initially it might be tempting to write off those areas that have experienced the internal combustion engine for the first time at close quarters. Change is happening in Nepal at a staggering pace, despite its underdeveloped status. However – and this must be stressed most emphatically – do not believe for one minute that the Annapurnas have lost their shine.

There are many new and exciting routes opening across the greater Annapurna region. The guide is divided into three parts, covering established routes, restricted area treks and new homestay trekking areas.

THE EARTHQUAKES OF 2015

In April and May 2015 two powerful earthquakes struck Nepal, causing massive disruption to the country. Although many older houses and some historic temples were left in ruins, across Kathmandu the majority of buildings and infrastructure remained intact. Sadly the rural regions adjacent to the two quakes suffered more serious damage. The main areas affected were below the peaks of Manaslu, Ganesh Himal, Langtang, Gauri Shankar and parts of the Everest region.

The entire Annapurna region, including Upper Mustang and Nar-Phu, was miraculously spared any significant damage. The villages, lodges, trails, roads and hillsides were left intact; only a few isolated houses suffered. Transport links between Kathmandu and Pokhara, as well as along the main valleys of the Kali Gandaki and Marsyangdi in the Annapurna region, remain open and are functioning normally.

We were in Kathmandu during the month of May. Having become instant aid workers (buying up rice, tarpaulins, tin sheets and warm, locally made clothing using generous donations), we witnessed a remarkable few weeks in the country. After the first days of shock, thousands of local people, young and old, engaged in the relief and rebuilding process with amazing energy. There is no doubt that the resilient people of Nepal will be back on their feet well ahead of expectations.

There is no reason for any prospective trekker to the Annapurna region (and much of Nepal) to delay a trip to the Himalayas. The country certainly needs the tourism sector to blossom again as soon as possible. Your trek will help this to happen more quickly.

Anyone wishing to know how ‘amateur’ aid works can read our Earthquake Diaries: Nepal 2015, published by CreateSpace/Amazon. (ISBN: 978 1 51506 316 2).

Annapurna Circuit

Most of the changes over recent years affect this route, so much of the guide concentrates on this trek, introducing some previously neglected side trips and new alternatives to walking on or close to the new ‘roads’. It remains the classic trek and is still a top trekking destination. Roads may change it but will not destroy it (after all, Switzerland has both side by side).

Annapurna Sanctuary

Another classic favourite where little change, other than ever-improving comfort, has occurred. The views from this cloud-bubbling cauldron are still hard to beat.

Ghorepani Circuit

Affectionately known as the Poon Hill Expedition, this has all the ingredients for a short, spell-binding adventure in the foothills. Terraced hillsides, fairytale forests and soaring snow-covered spires contrive to make any visit a memorable one.

Annapurna–Dhaulagiri

Once a hidden treasure, this route is gradually becoming more popular. Still mainly a camping option, its high isolated ridges will soon see an influx of trekkers, as community homestays open along its lower reaches. The airy belvederes of the Kopra Danda ridge are sensational; even the most experienced trekking hand will be blown away.

Restricted areas

Many would-be explorers are drawn to the captivating Tibetan culture and the plateau’s fantastic scenery. In these remote mountains, specialist trekkers can delve into the natural world, capturing magnificent predators like lammergeyer on camera, tracking the bashful Himalayan bear, sniffing out the elusive snow leopard and even yearning for the yeti.

Mustang

Mani wall in Mustang

Upper Mustang, with its extraordinary walled city of Lo Manthang, has long been the fabled Shangri-La. Getting there is every bit as fascinating and inspiring. Where in the world can you find such unbelievable variation – the highest peaks of the Himalayas, mysterious canyons, legend-filled settlements, staggering geology and contorted natural landscapes?

Nar-Phu

Perhaps the most astonishing region of all the Annapurnas, Nar-Phu is as barely known as it is inaccessible. Cut off for centuries by the highest passes and the most impenetrable, sheer-sided canyon in Nepal, the medieval villages of Nar and Phu are some of the country’s most closely guarded secrets. Trekking here takes one to a new level of adventure and wonder.

Other treks

Long overlooked are two routes below Machhapuchhre: the Mardi Himal Trek and the Machhapuchhre Trek. Both climb above the tree line to the wild, rugged base camps of Mardi Himal.

Lower down the hillsides trekkers can enjoy close contact with local people and their villages; eco-friendly, cultural homestay treks are the new thing. West of Poon Hill on the sunny slopes above the Kali Gandaki River are the Parbat Myagdi treks. Not far from Pokhara is the Siklis Trek; once popular with camping groups, it remains a peaceful and traditional area. The Lamjung foothills – around Chowk Chisopani–Tandrangkot–Puranokot – are the latest area to introduce homestay trekking. A little further north, the Gurung Heritage Trail is sure to be enjoyed by increasing numbers of trekkers in the future.

The joy of discovering these routes must be tempered with some words of warning: no trek to the remote Himalayan region can be underrated in terms of objective danger. Sections of this guide are devoted to the essential advance planning that is required by any potential visitor, especially because of the isolation, difficulty of access, and sheer ‘different-ness’ of the destination.

Having spent over half our lives trekking in Nepal, we have never tired of the Himalayas. Our youthful romantic notions about these distant, lofty peaks have not dwindled with age – we find ourselves drawn to these mountains, time and time again. It is an addiction that is hard to shed, so beware – you too may find that the ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ trek becomes habit-forming!

Geography

Climbing from Putak with the Thorong La in view (Trek 1)

Stretching over 2500km from the Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh in the east to Pakistan in the west, the Himalayas form an unbroken chain that divides the plains of India from the Tibetan plateau. Nepal is 250km wide on average and roughly 800km in length. The country’s highest peaks, from east to west – Kangchenjunga, Makalu, Everest, Lhotse, Annapurna and Dhaulagiri, all exceeding 8000m in height – are located along its northern borders.

From fossil records in Nepal and Tibet, it is estimated that a sea existed in this area about 100 million years ago. At some time in the following 50 million years India began to ‘collide’ with Tibet through the process of plate tectonics. Some 40–45 million years ago, the Indian plate continued its northward march, forcing the Tibetan plateau upwards. Around 20 million years ago, the main Himalayan chain was formed by the same process. The Himalayas have continued to rise over the last two million years.

Nepal’s border region with India, a narrow, once-malarial jungle strip called the Terai, has been cleared for agriculture and today provides the majority of the population with food. Rising abruptly from the plains of India are the Siwalik Hills: dramatic, steep, yet fragile, being easily denuded by the heavy rains. The steep and forested Mahabharat Hills, rising to over 3000m, mark the southern edge of the middle hills of Nepal, where most of the rural population lives. Most visitors trek through this area – home to the valleys of Kathmandu and Pokhara – marvelling at the impressive farming terraces and rolling hills dotted with quaint houses.

The Himalayan mountains comprise a relatively small zone along the northern border with Tibet/China, but are the visual focus of the whole country. The main Himalayan range is not a watershed; dynamic fast-flowing rivers cut through these mountains, giving access to the inner sanctuaries of the peaks. The main watershed ranges are north of the Nepal Himalayas in Tibet – equally astonishing and alluring mountains – with an altitude range of roughly 3000–8848m (the summit of Everest).

Climate

To see the greatness of a mountain… one must see it at sunrise and sunset, at noon and at midnight, in sun and in rain, in snow and in storm, in summer and in winter and in all the other seasons.

The Way of the White Clouds, Lama Anagarika Govinda

The Himalayas are an amazing natural barrier that divides the main weather systems of Asia, affecting the climate in a unique manner. The southern Indian plains experience hot, humid monsoon patterns in the northern hemisphere summer, with cooler, dry, high-pressure-dominated winter periods. In Tibet to the north the climate is harsh, cold and windy. The mountains cause a rain shadow creating a desert-like region, with only the far south of Tibet experiencing any influence of the monsoon. The Annapurna range sits between these two extremes, making a trek in the south very different from one in the north. It is these contrasting climates that make the Annapurna Circuit trek one of such variety. For the specific effects of the climate on trekkers see ‘When to go’.

Plants, animals and birds

Plants

Poinsettia

Nepal is a paradise for botanists. With so many climatic zones, it’s no surprise to find that there are in excess of 6500 different types of plants, flowers, trees, grasses and growths of all dispositions across the country. Many of the plants favoured by gardeners in the West have their origins in the Himalayas; Joseph Hooker, a noted 19th-century explorer and botanist, discovered many of these as he explored Sikkim and eastern Nepal.

Rhododendron

The lowland jungles and slopes of the Siwalik foothills are home to sal trees, simal, sissoo, khair and mahogany. Hugging the Mahabharat ranges and higher you find the ubiquitous pipal and banyan trees, like an inseparable couple shading porter rest-stops (chautaara). Chestnut, chilaune and bamboo occur in profusion, and in the cloud forests are a myriad of lichens, ferns, rattens and dripping lianas. The prolific orchids, magnolia, broadleaf temperate oaks and rhododendron (locally called laliguras) colonise the higher hillsides. Higher up are spruce, fir, blue pine, larch, hemlock, cedar and sweet-smelling juniper. Poplar and willow are found along the upper tree line; in the high meadows look out for berberis. Even in the highest meadows, hardy flowers and plants, such as colourful gentians, survive.

Animals

With such a wide variety of plantlife and breadth of climatic range Nepal is home to a diverse population of mammals, reptiles and birds. The lowland Terai is home to the spectacular Asian one-horned rhino, elephant, spotted deer and sambar deer, as well as the odd sloth bear, leopard and tiger, which are rarely seen. Gharals, marsh mugger crocodiles, alligators and snakes lurk in the murky waters of the lowland marshes and rivers that drain into the holy Ganges River. These once-thick jungles still host an amazing number of semi-tropical birds, despite clearance for agriculture. The middle hills are extensively cultivated, but still hide a variety of animals. Monkeys and langurs abound in the forests.

At altitude look for marmot, pika (small mouse-like animal, related to the rabbit), weasel, ermine, Himalayan hare, brown bear, wild dog, blue sheep, Tibetan sheep, wolf, thar (species of large deer) and the famed musk deer (a prized trading item in the past). Skittish wild ass, the kyang, are only found in the northern zones of Mustang and Nar-Phu. Wild yaks do still roam in isolated, remote valleys, but most are now domesticated. As well as the infamous butter tea, yak milk is also used by nomads to produce cheese and yoghurt. The dzo – a cross between a yak and a cow – is commonly used as a pack animal. Herders keep sheep and goats, as well as yaks. The snow leopard is rarely encountered and virtually never photographed. Hunting blue sheep in the dawn or twilight hours, they are extremely wary and unlikely to show themselves. Television crews with big budgets have waited many years to get any film of these beautiful creatures. If you see a yeti, do let us know!

Note that trekkers need not worry about encountering dangerous animals in the Annapurnas in general, although domestic guard dogs occasionally show more interest than is desirable.

Birds

(contributed by Rajendra Suwal, WwF Nepal)

The incredible diversity of the Annapurnas offers naturalists the perfect environment for discovering a wealth of birdlife. Its unique habitats shelter diverse groups of bird species. Birds move mostly in flocks, hunting insects at different levels in the forest. During quiet times you might spot 5–12 different species, determined by season. There are diurnal, seasonal and altitudinal migrants; birds such as the cuckoo visit during the spring for breeding.

As the first rays of sun hit the forests, the insects stir into life and the insectivores, including the colourful long-tailed minivet, and green-backed, black-lored and black-throated tits, begin foraging. Nectarine-, fruit- and berry-eating birds are active early in the day. Trees with berries or flowers are magnets for multiple species, namely whiskered, stripe-throated, rufous-naped and white-browed tits. The forest between Ghorepani and Tadapani is a good place to encounter the great parrotbill, spotted laughing thrush, and the velvet, rufous-bellied and white-tailed nuthatch.

The most rewarding forest habitats are those of Timang, Chame and Pisang, around Ghandruk, Tadapani, Ghorepani, Ghurjung and en route to Annapurna Base Camp. Try to catch a glimpse of the golden-breasted, white-browed and rufous-winged fulvetta. The forest is full of red-tailed, rufous-tailed and blue-winged minla. The tapping of the rufous-bellied, crimson-breasted and pied woodpeckers occasionally interrupts the silence. The forests are alive with the beautiful scarlet, spotted and great rose finch, along with the spot-winged grosbeak. Birdwatchers will be amazed to see tiny warblers, including chestnut-crowned, Whistler’s, black-faced, grey-hooded and ashy-throated warblers. Nepal cutia is found in forests of alder.

Smart sunbirds found in flowering trees include the black-throated, green-tailed, fire-tailed and purple sunbird. Fire-breasted flowerpeckers are found near settlements, in the flowering trees and mistletoe. Large-billed crows scavenge on kitchen leftovers or raid village crops. Flocks of red and yellow-billed chough forage around farms or high above the passes. The olive-backed pipit, magpie, robin and common tailorbird are found near farms, along with the common stonechat and the grey, collared, white-tailed and pied bushchat.

Streams and riverbanks are teeming with frisky birds. The pristine environment of the Modi Khola is a very rewarding habitat for river birds, including white-capped water redstart and plumbeous redstart; little, spotted, black-backed and slaty-backed forktail; brown dipper, grey wagtail and blue whistling-thrush. Other common birds are the red-vented, black bulbul, great and blue-throated barbet, and also coppersmith barbet in the lower reaches. On some overhanging cliffs below Landruk, Chhomrong and Lamakhet near Siklis are honeycombs made by the world’s largest honeybees, where you may spot the oriental honeyguide.

Ravens are acrobatic birds, seen in the alpine zones. The blue pine forest is a habitat of the very vocal spotted nutcracker, while orange-bellied leafbirds prefer the upper canopies. More treasures are the tiny Nepal, scaly-breasted and pygmy wren babblers, feeding under the ferns, with their high-pitched territorial calls. With its high-pitched sound, the jewel-like, tiny chestnut-headed tesia is a wonderful bird to see in moist undergrowth.

The mountains near Lete and Ghasa harbour all the pheasant species found in Nepal, namely the kalij, koklass and cheer pheasant. Shy by nature, one can hear them before dawn. In the rhododendron and oak forest look for ringal, and in cane bamboo watch for satyr tragopan and blood pheasant. The Himalayan munal, the national bird of Nepal, favours the tree line and pastures.

The Kali Gandaki River Valley is one of the major ‘flyways’ of migratory birds, including demoiselle cranes, birds of prey, black storks and many varieties of passerines. Migrating eagles, including the steppe and imperial, as well as small birds of prey, pied and hen harriers and common buzzards also use it. Observing the annual autumn migration of thousands of demoiselle cranes is very rewarding. To gain height and glide over the peaks, they catch the thermals in the windshadow of the mountains. If the weather turns bad, they wait in the buckwheat fields and riverbanks. The golden eagle, the master predator, anticipates their arrival and attacks the cranes in-flight, occasionally separating a young, injured or sick crane from the flock, catching them in the air. This epic migration was broadcast as part of the ‘Planet Earth’ Mountain Series on the BBC/Discovery Channel.

The skies of Annapurna host the vulture and majestic lammergeyers (with 3m wingspans). Himalayan and Eurasian griffons soar, lifting every onlooker’s spirit. Some ethnic groups of Mustang practise sky burial and believe the vultures pass the spirits to the heavens. Cliffs are breeding sites for vultures and lammergeyer. All the vulture species of Nepal, including the Egyptian vulture, the endangered white-rumped, the red-headed and the globally endangered slender-billed vulture are found in the foothills. Cinereous vultures are seen in winter.

In the caragana bush habitat of Muktinath, Jharkot and Jomsom, look for the white-browed tit-babbler, white-throated, Guldenstadt’s and blue-fronted redstart, brambling and brown rufous-breasted and Altai accentor. Rock bunting and chukor partridge inhabit areas between Kagbeni, Muktinath, around Manang and south to Lete. In the air you can observe the speedy insect-hunter white-rumped needletail, Nepal house martin, red-rumped swallow and Himalayan swiftlet. Finally, near the Thorong La, observe the Himalayan snow cock and flocks of snow pigeons foraging near trails, oblivious of passing trekkers.

Brief history

Nepal is one of the most diverse places on earth, its culture and people as varied as its scenic attractions. With a long history of isolation, the country and its once mystical capital, Kathmandu, has an amazing story to tell. Its history is a complex blend of exotic legend, historical fact and religious influence, suffused with myth.

The original inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley were the Kiranti people. Around 550BC, in Lumbini in southern Nepal, Prince Siddhartha Gautama was born, later becoming the Buddha, whose philosophy would have such an impact on the country. In the third century BC, Ashoka, one of the first emissaries of Buddhism in India, built the ancient stupas (a large Buddhist monument, usually with a square base, a dome and pointed spire) of Patan and the pillar in Lumbini. Around AD300, during the Licchavi Period, the Hindu religion blossomed across the southern and middle hills. Trade routes flourished between Tibet and India, with Kathmandu being the most important trading centre.

When Buddhism declined in India, ‘adepts’ (masters of Buddhism) crossed the Himalayas to find refuge in Tibet. Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism later trickled back into Nepal, providing many of the fascinating aspects of the country’s religious life. The Buddhist master Padma Sambhava (Guru Rinpoche) travelled around the Himalayas in the eighth century. Few records exist of the period following until the 13th century, when the Malla kings assumed power.

The Malla period marks the golden age of art and architecture in Nepal, with the construction of multi-tiered palaces and pagodas. The people lived in decorated wood and brick houses. Jayasthiti Malla, a Hindu, consolidated power in the Kathmandu Valley and declared himself to be a reincarnate of the god Vishnu, a practice that was considered appropriate for the monarchs of Nepal until 2007. Jyoti Malla and Yaksha Malla enhanced the valley with spectacular structures. Around 1482 the three towns of Kathmandu, Patan and Bhaktapur became independent cities, with each king competing to build the greatest Durbar Square, parts of which still exist today.

Durbar Square. Patan

From a hilltop fortress above the town of Gorkha (Gurkha) came Prithvi Narayan Shah. His forces swept in from the west, subduing the cities of the Kathmandu Valley and unifying Nepal. Nepalese armies invaded Tibet in 1788, but were later repulsed by Tibet with Chinese intervention. In 1816 the British defeated the Gurkhas and, in the treaty of Segauli, Nepal had to cede Sikkim to India, with the current borders delineated. The British established a resident office, but Nepal effectively became a closed land after 1816.

In 1846 a soldier of the court, Jung Bahadur Kunwar Rana, took power after a bloody massacre in Kot Square in Kathmandu. The queen was sent into exile and the king dethroned. For the next 100 years the Rana family ruled Nepal, calling themselves Maharajas. Family intrigues, murder and deviousness dominated the activities of the autocratic Ranas. The country remained closed to all but a few invited guests, retaining its medieval traditions until 1950.

After Indian independence in 1947, a Congress Party was formed in Kathmandu. The powerless king became a symbol for freedom from the Ranas’ rule. For those who dared to confront the Ranas, there was a terrible price to pay; many suffered the death penalty. King Tribhuvan finally ousted the Ranas in 1951.

A coalition government was installed, with a fledgling democracy. The country opened to visitors and Mount Everest was climbed in May 1953. King Tribhuvan died in 1955 and his son Mahendra assumed power. In 1960 Mahendra ended the brief experiment with democracy, introducing the party-less panchayat system, based on local councils of elders with a tiered system of representatives up to the central parliament. In 1972 King Birendra became the new king, but his coronation did not take place until the spring of 1975, on an auspicious date. In 1980 a referendum was held and the panchayat system was retained. After 1985, rapid expansion brought many changes; the population grew astonishingly, and the traditional rural lifestyle of the valley began to disappear under a wave of construction.

In April 1990 full-scale rioting and demonstrations broke out, forcing the king to allow a form of democracy to be introduced. But political corruption and infighting did little to enhance the democratic ideals, and in the late nineties a grass roots Maoist rebellion developed. Many had genuine sympathy with the need for greater social equality, but violence and demands for a leftist dictatorship met with resistance. In a tragic shooting spree in June 2001 King Birendra and almost his entire family were wiped out by his son, Crown Prince Dipendra. King Birendra’s brother Gyanendra became king, but in October 2002 he dissolved parliament and appointed his own government until elections could be held. Meanwhile the Maoist rebellion continued to threaten all parts of the country. Coercion and intimidation were rife in the countryside and no solutions were in sight.

King Gyanendra relinquished power in April 2006 and the Maoist leaders entered mainstream politics after winning a majority of votes in the election. Since then, the government of Nepal has been in freefall, with a political stalemate and paralysis derailing development. A new constitution was finally promulgated in September 2015, but it remains to be seen where the ruling elite will take the country. Tourism is still one of the main foreign exchange earners, but an increasing number of young Nepalese are seeking work outside the country, particularly in the Arabian Gulf. Despite the political uncertainty, tourists are still made to feel very welcome in the country.

People of Nepal

Children in Bhaktapur

At the latest estimate there are around 32 million people living in Nepal. (In 1974 there were a mere eight million.) There are at least 26 major ethnic groups, with the majority of these living in the middle hills. In general, the people in the southern zones are Hindu followers while those from the high Himalayan valleys are Buddhist. However, there is no clear traditional divide in the major valley of Kathmandu, and many thousands of villagers ‘escaped’ from the effects of the Maoist insurgency to the safety of Kathmandu.

The Newaris – a mix of Hindus and Buddhists – are the traditional inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley. The Tharu are a major group from the lowland Terai, with their ancestry probably linked to Rajasthan in India. Other people of the Terai, also related to Indian Hindu clans, are collectively known as the Madhesi. The first President of Nepal, Dr Ram Baran Yadav, comes from this ethnic group.

The rural hills of the Annapurna region are home to Magars, Chhetris, Gurungs and Brahmins (technically high caste). Gurung men are particularly noted for their service to the Gurkhas. Thakalis live along the Kali Gandaki. Manangis inhabit the higher reaches of the Marsyangdi.

Religion

Holy places never had any beginning. They have been holy from the time they were discovered, strongly alive because of the invisible presences breathing through them.

The Land of Snows, Giuseppe Tucci

Paintings in Jhong Gompa (Trek 1)

Religious beliefs and practices are an integral part of life in Nepal. To comprehend the country’s culture would be impossible without a basic understanding of the religious concepts.

Hinduism

Hinduism is the main faith of Nepal; until recently the country was a Hindu kingdom. Evidence of the Hindu faith in the Annapurnas manifests itself mainly through the festivals and celebrations of the people, rather than in an abundance of elaborate temples; it is as much a way of life as a religion. A very definite attitude of fatalism is conveyed to the visitor meandering along the populated trails. The monsoon often brings the destruction of a hillside or village by a giant mudslide, for example; these are seen traditionally not so much as resulting from the uncontrollable actions of nature but from the vengeance of the gods. Your own bad actions might be the cause of such misfortune.

Many Hindu religious ideals have come from the ancient Indian Sanskrit texts, the four Vedas. In essence, the ideas of Hinduism are based on the notion that everything in the universe is connected through Karma. This means that your deeds in this life will have a bearing on the next.

Despite the apparent plethora of Hindu gods, they are in essence one, worshipped in many different aspects. The trinity of Hindu gods are Brahma, the god of creation; Shiva, the god of destruction; and Vishnu, the god of preservation. They manifest in many forms, both male and female. Brahma is rarely seen – his work is done. Shiva is the god of destruction but has special powers for regeneration. Shiva can manifest as Mahadev the supreme lord, or as dancing Nataraj, representing the rhythm of the cosmos. As Pashupati he is the Lord of Beasts. Bhairab is Shiva in his most destructive form, black and angry. In his white form he is so terrible that he must be hidden from view, daring only to be seen once a year during the Indra Jatra festival. (He lurks in Kathmandu’s Durbar Square behind a gilded wooden screen.)

Parvati is Shiva’s wife, with many aspects. As Kali and Durga she is destructive. The festival of Durga takes place during the trekking high season of the autumn, so don’t offend her or you may not get your trekking permit on time. Taleju is another image of Parvati.

Other popular gods and goddesses include Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, and the humorous elephant god Ganesh, worshipped for good luck and happiness.

The third God, Vishnu, is also worshipped in Nepal as Narayan, the preserver of life. Vishnu has 10 other aspects. The eighth avatar, the blue Krishna, plays a flute and chases after the cowgirls. Other notable avatars are Rama, of the Indian epic Ramayana, and the ninth avatar, the Buddha.

Hanuman is the monkey god, sometimes appearing as a rather shapeless stone and often sheltering under an umbrella. Machhendranath is a curious deity, the rain god, hailed as the compassionate one, and has two forms: White (Seto) and Red (Rato).

THE LEGEND OF GANESH

Ganesh is Shiva and Parvati’s son. But why does he have the head of an elephant? Parvati gave birth to Ganesh while Shiva was away on trek. When he returned, he saw the child and assumed that Parvati had been unfaithful. In a furious rage, he chopped off Ganesh’s head and threw it away. After Parvati explained, Shiva vowed to give Ganesh the head of the first living being that passed their home – it was an elephant.

Buddhism

Buddhist gompa in upper Pisang (Trek 1)

Buddhists are found in the Kathmandu Valley and in the northern regions of the country. Buddhist monasteries (gompas) and culture are encountered on the Annapurna Circuit beyond Tal, around Muktinath and south along the Kali Gandaki River as far as Ghasa. Mustang and Nar-Phu are also Buddhist.

Buddhism is a philosophy for living, aiming to bring an inner peace of mind and a cessation of worldly suffering to its adherents. Reincarnation is a central theme; the essence of the soul is developed through successive lives until a state of perfect enlightenment is attained. Prince Siddhartha Gautama, the earthly Buddha, was born to riches but his daily life was one of spiritual torment. He left his wife and newborn son to become an ascetic, wandering far and wide, listening to sages, wise men and Brahmin priests. However, he found no solace until he achieved enlightenment through the Middle Path.

Buddhism has two branches: Hinayana and Mahayana. The latter path is followed in Nepal and Tibet, where it has evolved into a more esoteric philosophy called the Vajrayana (Diamond) Path. It blends ancient Tibetan Bon ideas with a phenomenon known as Tantra, meaning ‘to open the mind’. Tantra basically asserts that each person is a Buddha and can find enlightenment from within.

The dazzling proliferation of Buddhist artistry and iconography is startling. Even the most sanguine atheist will surely find something uplifting about Nepal’s rich and colourful Buddhist heritage.

The following Buddhist sects are found across the Annapurna region:

Nyingma-pa is the oldest Buddhist sect; its adherents are known as the Red Hats. Guru Rinpoche was its founder in the eighth century AD. Today the Nyingma-pa sect is found across the high Himalayas of Nepal, in Tibet, Spiti and Ladakh.

Kadam-pa was developed by Atisha, a Buddhist scholar from northern India, during his studies at Toling Gompa in the Guge region of Western Tibet. He suggested that followers should find enlightenment after careful reflection and study of the texts.

Kagyu-pa is a sect attributed to the Indian mystic translator Marpa (AD1012–97), a disciple of Atisha. Adherents concentrate their meditations on inner mental and spiritual matters, following the wisdom of their teachers. The Kagyu-pa sect split into a number of sub-groups, such as the Drigung-pa, Druk-pa, Taglung-pa and the Karma-pa.

Sakya-pa began in the 11th century under Konchok Gyalpo from the Sakya Gompa in Tibet. Followers study existing Buddhist scriptures and created the two great Tibetan Buddhist bibles, the Tangyur and Kangyur.

Gelug-pa is the Yellow Hat sect of the Dalai Lama. Tsong Khapa, the 14th-century reformer, redefined the ideals of Atisha and reverted to a more purist format, putting more emphasis on morality and discipline.

Bonpo

Bon idol, Kunzang Gyalwa Dupa, Naurikot (Trek 1)

In 1977 the Tibetan government-in-exile recognised and accepted the ancient Bon as a Tibetan sect. The Bon’s spiritual head is the Trizin, and its spiritual home is the Triten Norbutse Gompa; anyone interested in Bon should visit the complex near Swayambhunath, such is the rarity of any active Bon culture today. The Bonpo worshipped natural phenomena, like the heavens and mountain spirits, as well as natural powers such as rivers, trees and thunder. The chief icon of the Bon is Tonpa Shenrap Miwoche. The Bon seek the eternal truth and reality of life, as do Buddhists.

See Appendix B for further details. Other religions with a limited following in Nepal are Islam, Christianity, Sikhism and Shamanism.

Festivals

Nepal has an extraordinary number of festivals – any excuse for a good celebration! During the high season for trekkers, the Dasain and Tihar festivals can occasionally disrupt those trying to obtain the necessary trekking documents. During Dasain, the goddesses Kali and Durga are feted and the terrifying white Bhairab is allowed out of his cage in Kathmandu’s Durbar Square. (Blood sacrifices are the most noticeable aspect of these celebrations; these are not for the squeamish.) Tihar is a much more light-hearted affair, with crows, dogs, cows and brothers celebrated on different days before a final party night of fairy lights and candles.

During the early spring, trekkers may witness Losar, the Tibetan New Year, celebrated primarily at Boudhanath. Tibetan drama and colourful masked Cham dances can be seen; the Black Hat dance celebrates the victory of Buddhism over Bon. Mi Tsering, the goblin-like clown, mocks the crowd with great mirth.

In spring at Pashupatinath is Shiva Ratri: the night of Shiva. Holi is another festival celebrated across the country. Watch out during this festival, as coloured dyes are thrown at passers-by; tourists and trekkers are fair game! The cavalcade of the white Seto Machhendranath idol also takes place in spring, when a tall wooden chariot housing this rain god is dragged through old Kathmandu, often pulling down power lines and brushing the top storeys of the old brick houses of Asan. A similar festival takes place in May, when the red Rato Machhendranath is hauled around Patan and back out to Bungamati.

Cultural considerations

Despite contact with the outside world since 1950, Nepal remains a conservative country, especially in the remoter hilly districts. Avoid overt expressions of affection and always dress modestly – anywhere in Nepal – to avoid causing offence. Skimpy shorts and tops are fine in St Tropez, but wearing such attire here could cause embarrassment (and invariably some lewd comments from the locals behind your back). In the icy confines of the high mountains, an inappropriate state of partial undress is unlikely to be an issue – unless you have already become an ascetic!

It’s a rare thing for a non-believer to be allowed into the inner sanctuaries of Hindu temples anywhere across the country; remember that leather apparel, belts and shoes are not permitted inside. When visiting monasteries, remove trekking hats and boots before entry. Small donations are appreciated in monasteries and photographers should ask before taking pictures inside. On the trail, keep to the left of mani walls and chortens (religious devotional structures: see Appendix B) and circle them in a clockwise direction. The mantra ‘Om Mani Padme Hum’ – Hail to the Jewel in the Lotus – is inscribed on these walls, on stones and on prayer wheels.

Buddhist chortens, Tange, Mustang (Trek 5)

If you are invited into a local house, remember that the cooking area, hearth and fire are treated with reverence. Do not throw litter there. Never sit in such a way as to point the soles of your feet at your hosts, or step over their feet. Avoid touching food, and be careful to eat with your right hand if no utensils are available. Never touch a Nepali on the head.

Begging

Begging is endemic in Nepal, possibly putting a brake on development and local initiative. Seen from the Nepalese point of view, all foreigners are rich, and therefore fair game to be enticed into parting with some of their hard-earned cash. Ordinarily no one will mind this, but in the long term local people need to be helped to help themselves; simply handing out money is not the answer.

Begging is not confined to the poverty-stricken lower classes; even the higher echelons have the same attitude – there will always be some rich overseas government to build a road or desperately needed hydro plant, and so on. Western governments, the UN and large donors continue to ignore the unaccountability of bribery and slush funds, while boasting about how much they give to the poor.

The world still seems to see Nepal as a begging-bowl case. In fact, the wealth of talent in the country is amazing; the ‘make something from nothing’ and the ‘make do and mend’ culture shows a level of ingenuity that has almost disappeared in the throwaway societies of the developed world. Given the opportunity, Nepal will flourish and prosper.

Helping the community

The world’s big donor organisations and charities hold a soft spot for Nepal. This is in no small part due to its welcoming and charismatic people, many of whom are exceedingly industrious. The effect of these multinational donations is not often felt directly by the majority of the people, so there is plenty of scope for small initiatives to be implemented by visitors who wish to help. Often it is these projects – improving village water supplies or local electrification, for example – that really make a difference. Check out some of these local projects below.

Autism Care Nepal (www.autismnepal.org) There was very little knowledge of this condition in Nepal when their son was diagnosed with autism, so two Nepali doctors founded this organisation to raise awareness and help others in the same situation.

Beni Handcrafts (www.benihandcrafts.com) products are made by women forced to move from the hills to the city, providing them with training, employment and income for their families. Beni and her team collect sweet wrappers, inner tubes and other waste from the streets of Kathmandu as well as mountain trails. The rubbish is then made into attractive and functional products. View and buy them at the Northfield Café in Thamel.

Steps Foundation Nepal (www.stepsfoundationnepal.org) is a charity supported by profits from Beni Handicrafts. It works on the step-by-step principle that through education for all and increasing awareness of hygiene, the health and well-being of families will be improved.

Kathmandu Environmental Education Project (KEEP) (www.keepnepal.org) was established in 1992 to ‘provide education on safe and ecologically sustainable trekking methods to preserve Nepal’s fragile eco-systems’. Based down a lane off Tri Devi Marg in Thamel, they give vital information to trekkers, harness tourism for development, run environmental seminars, manage a porters’ clothing bank, and help to promote a more professional ethos while improving the skills of tourism professionals. They run volunteer programmes and conduct wilderness first aid training.

Local school in the foothills of the Annapurnas

Community Action Nepal (www.canepal.org.uk), co-founded by mountaineer Doug Scott, seeks to improve the infrastructure of villages in the middle hills by building schools, health posts and clean water projects, and developing cottage industries.

Choice Humanitarian (www.choicehumanitarian.org) is seeking to end poverty by concentrating on sustainable village development through tourism. The aim is to empower village people, generally with neither funds nor skill, to improve their own prospects.

Mountain People (www.mountain-people.org) ‘Helping mountain people to help themselves’ is an independent, non-profit, non-political, non-religious and cross-cultural organisation. They help with schools, porter welfare, women’s projects and bridge building. Their operations centre is in the Hotel Moonlight in Paknajol, Thamel.

The International Porter Protection Group (IPPG) (www.ippg.net) was started in 1997 to raise awareness about the conditions and plight of all-too-frequently exploited porters. Their task is to focus on the provision of clothing, shelter and medical care for often-overlooked working porters in Nepal.

PORTER WELFARE

Look after your friendly porter

Every year porters die on the mountain trails of Nepal, and very occasionally some of them are in the employ of foreign trekkers. Fortunately today there is much more awareness about the possible dangers faced by porters, partly because of some high-profile accidents in the past. Exploitation has always been a part of Nepalese society; the caste system, which still pervades the roots of its culture, ensures that each person knows his status. However, visitors need not adopt such attitudes. Following the Maoist insurgency, general wage levels for porters and once badly treated workers throughout society have risen dramatically – perhaps the only benefit of that long reign of violence! Two organisations have made an impact on porter welfare, the International Porter Protection Group (see below) and Tourism Concern (www.tourismconcern.org.uk). Trekking agencies in Nepal are now expected to provide adequate insurance for all their staff.

The following are some outline guidelines for all trekkers:

Ensure that your porters have adequate clothing and equipment for the level of trek you are undertaking: footwear, hat, gloves, warm clothing and sleeping bags or blankets as necessary.

Be prepared with extra medicines for your porters, and don’t abandon them if they are sick; carry funds for such a situation.

Group trekkers can make themselves aware of the policy of their chosen agent and keep an eye on the reality on the ground.

Naturally it is hard for trekkers to really know what is going on behind the scenes; the Nepalese are masters at appealing to the sympathetic nature of visitors to the country.

Developing rural areas through tourism

Tourism is one way in which the culture and livelihoods of the upland people can be sustained in the long term. The major trekking trails have experienced the growth of trekking tourism since the 1960s and the effects have generally been positive. The difficulty is finding the right balance, by improving local living conditions without destroying the existing environment and culture. It is not a unique problem to Nepal, as anyone who has visited other popular mountain destinations – even Chamonix or Zermatt – will have observed. As visitors we have our own views about development but ultimately it is the local people and the different tourism agencies that decide on the future of their region.

The fragile environment of the Himalayas is becoming an ever-pressing concern with global warming, just as it is across the globe. Unless the rural community is served well by tourism, decline is inevitable. Already there is a shortage of manpower in the hills as young people seek better pastures overseas in the Gulf and Malaysia.

Getting there

Karjung Kang peak, above the trail towards Damodar Himal (Trek 6)

Flights to Nepal

The main airlines currently flying to Kathmandu are:

Air Arabia From The Gulf

Air India Via Delhi, Kolkata (Calcutta) and Varanasi

Air Asia Via Kuala Lumpur; low-cost carrier

Bangladesh Biman Via Dhaka; for budget travellers with time to kill

Air China Links Kathmandu with Lhasa, Chengdu and Guangzhou (Canton)

Dragon Air From Hong Kong

Druk Air From Paro, Bhutan, to Kathmandu and on to Delhi

Etihad Airways Via Abu Dhabi from Europe

Fly Dubai From Dubai

Gulf Air Via Bahrain or Abu Dhabi

Indigo Cheap Indian carrier

Jet Airways (India) Good through-service from London to Nepal via Delhi and Mumbai

Korean Airlines From the Far East

Nepal Airlines From Delhi, Bombay, Dubai and Hong Kong – for those with bags of time

Oman Air Via Muscat

Silk Air From Singapore

SpiceJet Low-cost Indian carrier

Thai Airways Via Bangkok, from Europe and Australia/New Zealand

Turkish Airlines Via Istanbul

Qatar Airways Via Doha from Europe

Virgin, BA and other major airlines To Delhi; then one of the Indian carriers to Kathmandu.

This information is, naturally, subject to change. Check the internet or your local travel agent for the latest information.

Overland routes to Nepal

There are several overland routes into Nepal from India and Tibet/China. Land borders with India are at Sonauli/Belahiya near Bhairahawa; Raxaul/Birgunj; Nepalganj; Mahendranagar; and Kakarvitta. The most-used entry point from India is the Sonauli/Belahiya border north of Gorakhpur. Buses connect Bhairahawa to Kathmandu and Pokhara. The Banbasa/Mahendranagar western border links Nepal to Delhi, but it’s a long journey by local transport. Those travelling between Kathmandu and Darjeeling or Sikkim use the eastern border at Kakarvitta.

Kathmandu is linked to Lhasa in Tibet by the Arniko/Friendship Highway through Kodari/Zhangmu. It is a spectacular three-to-four-day journey, climbing over several 5000m passes through Nyalam, Xigatse and Gyangtse to Tibet’s once-forbidden capital, Lhasa.

Getting to Dumre and Pokhara

Many trekkers fly to Pokhara – a short flight from Kathmandu. On a clear day, stupendous views of Langtang, Ganesh Himal, Himalchuli, Manaslu and the Annapurnas grace the northern frontier. Airlines serving Pokhara (roughly US$115 single) include Yeti Airlines/Tara Air, Buddha Air and Goma Airlines, departing from the domestic terminal next to the international airport. Planes to Jomsom depart from Pokhara soon after dawn, so an overnight stay in Pokhara is necessary.

Travelling to Pokhara (200km) by bus is quite straightforward these days, since the road has been improved all the way. The normal journey time is six to eight hours, but traffic can get heavy in the afternoon if you are heading back towards Kathmandu. The most luxurious bus is currently the Greenline service: US$25 including a great lunch at the Riverside Springs Resort about halfway to Pokhara. Other slightly less comfortable (but generally reliable) tourist buses depart around 7am from Kantipath near Thamel. ‘Local’ buses, which are even cheaper, leave from the Gongabu bus depot, northwest of the city, but are only recommended for those wishing to rub shoulders (and more) with the locals and their animals all day. The taxi fare to the bus depot is normally more than the bus ticket, so there is little to recommend this option. Local buses often stop in Mugling, an infamous, scruffy village 110km west of Kathmandu – eating lunch here has its risks. In days gone by, dishes of ‘hepatitis and rice’ were served up.

The road plummets steeply down after leaving the Kathmandu Valley. On a clear day you will see Ganesh Himal, Himalchuli and maybe Annapurna II. The road descends through Naubise then soon follows the Trisuli River, passing through Charaudi, Malekhu and Majhimtar. Buses continue past the Manakamana cable car station for the temple shrine, and on to Mugling. Rafting parties can be observed on the Trisuli. From Mugling the road follows the Marsyangdi River through Ambo Khaireni, the turn-off for Gorkha town. At km135 is Dumre, where Annapurna Circuit trekkers need to wake up and change buses for Besisahar. Otherwise it’s on to Pokhara and, with luck, views of Himalchuli, Lamjung, Annapurna II and IV, along with Machhapuchhre; all are simply dazzling in the afternoon light. From Pokhara at sunset this astonishing panorama is truly heaven-sent – a vision that guests have marvelled at since Annapurna was ‘discovered’.

EARLY EXPLORERS TO ANNAPURNA

Annapurna I sunset from Kalopani (Trek 1)

When Nepal first opened to foreigners in the 1950s a few parties entered through the border south of Pokhara. French alpinists Maurice Herzog, Louis Lachenal, Lionel Terray, Gaston Rebuffat and others were granted access to Nepal in the spring of 1950. Despite having ambitions to summit the higher peak of Dhaulagiri, they settled for Annapurna I. Much of the arduous adventure was spent finding access routes to the mountain and its lower ramparts. Herzog’s party succeeded in summiting Annapurna I on 3 June, making it the highest peak over 8000m attained, but the cost of the expedition on his and Lachenal’s frostbitten fingers and toes are the abiding memory for readers of his book.

A British-Nepalese Army Expedition succeeded on the North Face of Annapurna I, when Henry Day and Gerry Owens made the top – incredibly it was 20 years later. At the same time an attempt was made on the awe-inspiring buttresses of the South Face, seen from the Annapurna Sanctuary, by Chris Bonington’s team. Dougal Haston and Don Whillans tackled this treacherous face on 27 May 1970, just a week after Day and Owens.

Climbers from all over the world have been drawn to the Himalayas of Nepal ever since. The early climbers were backed by vast entourages of porters, cooks and crews to carry their tons of equipment. In the 1960s ex-Gurkha officer Jimmy Roberts decided that the local portering traditions of the country, which allowed goods to ‘reach all those parts that were hard to reach’, could be adapted for trekking.

Soon all manner of adventurers, hippies and travellers also flocked to the country. You are following in the steps of some illustrious climbers, explorers and, yes, ordinary modern-day adventure-seekers like yourself.

Visas and permits

Village house on the trek up to Chowk Chisopani (Trek 12 variant)

Nepal

All foreign nationals (except Indians) require a visa. Currently visas are available from embassies and overland borders, as well as at Tribhuvan International Airport on arrival in Kathmandu (check that this is still the case before arrival). Entering or exiting the country at the remoter crossing points and from Tibet may be subject to change, with the unpredictable political difficulties in some of these districts.

Applying in your home country is one option, although it will cost more. Be sure to apply well ahead of the time of travel, in case there are any holidays at the embassy related to the festival periods in Nepal. Many people obtain visas on arrival; at the present time this is the simplest option. The maximum length of stay in Nepal is five months in one calendar year (although the fifth month can sometimes be hard to obtain).

Tourist visas are available for 15, 30 or 90 days, at a fee of US$25, $40 and $100 (payment in cash) respectively. Check the up-to-date fees at www.nepalimmigration.gov.np. Those staying longer can get an extension in Kathmandu at the Immigration Department at a cost of US$30 (the minimum fee) or pay a daily charge of US$2 per day. All visas are currently multiple-entry, helpful for those heading out to places like Bhutan, Tibet or India and returning to Kathmandu for their flight home.

Note on Indian visas

Anyone planning to visit India as well as Nepal should be sure to check the latest visa situation. Changes to the fees, the period of the visa, re-entry rules, and probably new rules we can only guess at seem to be introduced quite frequently. It’s also important to note that obtaining a visa in Kathmandu for India at short notice takes at least a week and most likely more time to procure. There is a new online, pre-arranged visa system which may still be a little confusing.

Note on Tibet/China entry

Travel to Tibet from Nepal currently requires special arrangements. Do not get a Chinese visa in advance of your visit, as it will simply be cancelled at the Kathmandu embassy. Visas are normally issued on paper only for the duration of the stated itinerary, with extensions not possible. Allow for a few days in Kathmandu and make the application well ahead of your arrival in Nepal. Arranging the visa in Nepal must be through a Nepalese agent. Independent travellers can still visit Tibet by taking the ‘budget tour’ on offer through Kathmandu travel agents.

SOME NEPAL EMBASSIES

UK 12A Kensington Palace Gardens, London W8 4QU; tel: +44 (0207) 243 7854; email: eon@nepembassy.org.uk; www.nepembassy.org.uk

US 2131 Leroy Place, NW, Washington, DC 20008; tel: +1 (202) 667 4550; email: info@nepalembassyusa.org; www.nepalembassyusa.org

India Barakhamba Road, New Delhi 110001, India; tel: +91 (11) 2347 6200; email: consular@nepalembassy.in; www.nepalembassy.in

China (Consulate) Norbulingka Road 13, Lhasa, Tibet, People’s Republic of China; tel: +86 (891) 682 2881; email: rncglx@public.ls.xz.cn

For others see www.mofa.gov.np.

Trekking permits

All trekkers in Nepal are required to obtain permits before setting out on their expeditions. Both the documents below can be procured for a fee by trekking agencies in Kathmandu, or independently at the Bhrikuti Mandap building, south of Ratna Park bus depot, tel: 01 425 6909. The office is open every day except Saturday and public holidays.

Trekkers’ Information Management System (TIMS)

There are two types of permits for trekkers: Blue, issued through trekking companies, costing US$10; and Green for individuals, costing US$20 (maybe payable in rupees). TIMS cards can be issued on the spot in 30mins or so. Take a copy of your passport and two photos for the single-use card. Cards are valid for at least one month and longer if requested. See www.timsnepal.com.

Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP)

Visitors to the Annapurna region are also required to pay for entry to the ACAP zone that encompasses nearly all of the trails described in this guide. Currently the fee is Rs2000 (£15, $18) per person per single entry.

Note Single entry does mean just that; if you leave one part of the conservation area hoping to re-enter in another (for example, you cannot even get the bus from Beni to Birethanti), you will be refused – this means no rest and recuperation in Pokhara is permitted without payment again in full!

ANNAPURNA CONSERVATION AREA PROJECT

Meeting the locals in the Lamjung foothills

The Annapurna Conservation Area Project was established in 1986. Its aims were to regulate activities within the zone to promote conservation in tandem with community development. The project began work on developing more ecologically sound ways of improving the environment. One major aim was to reduce the destruction of the forests caused by traditional wood-burning cooking; other schemes sought to improve health and hygiene levels, as well as improving basic infrastructure. Bridges, schools, health posts, safe drinking water depots, kerosene dumps and regulation of trekkers have all brought significant benefits to locals and visitors alike. Preservation of the local culture is another key aim, and certainly the monasteries and historic places have seen the results of this sustaining project.

National Trust for Nature Conservation (NTNC)

PO Box 3712, Jawalakhel, Lalitpur, Nepal; tel: 977-1-5526571, 5526573; email: info@ntnc.org.np; www.ntnc.org.np; www.forestrynepal.org.

Trekking Agencies’ Association of Nepal (TAAN)

Tel: +977-1-4427473, 4440920, 4440921; email: taan@wlink.com.np; www.taan.org.np

See also www.welcomenepal.com and www.tourism.gov.np.

Permits for restricted areas

Lo Manthang harvest (Trek 5)

Prospective trekkers planning a trip to Upper Mustang, Damodar Kund or Nar-Phu do now require a company-issued TIMS card. These are normally procured by your trekking agency from the constantly moving immigration office. In addition, the areas require you to take a guide. All places to be visited should be mentioned in your application. Check www.nepalimmigration.gov.np for the latest information.

Upper Mustang

Currently a fee of US$500 is levied for the first 10 days, with an additional US$50 per extra day. However, recent information suggests that the intial fee might soon be lowered to US$100. Do check the relevant website (www.nepalimmigration.gov.np) for the latest information. Trekkers need to be familiar with the rules concerning conservation, ecology and cultural aspects when entering Mustang. Independent trekking in the Mustang region is not yet allowed.

Nar-Phu

Your trekking agent will normally obtain your permit, but if you need to go with him to get it be aware of the following anomalies. The permit is issued for one week, but officials will try to insist that it’s for seven days and only six nights, which immediately causes problems with the itinerary. The permit should have seven days written on it, but the fixed entry and exit dates might reflect the six nights. (Fortunately the checkpost in Koto is much more in tune with reality and automatically allowed us the correct seven-night period, and they also let one trekker in a day earlier than their permit stated. This means you do not need to be bamboozled into paying for another week, unless you plan some extra days for acclimatisation or additional walks from Phu or Nar; crossing the Kang La will not need an extra week.) It’s very unfortunate that extra days cannot be added to this permit, as for Mustang. Theoretically a group must be at least two trekkers, but if you are a lone visitor you can pay double to get the proper papers.

THE EVER-CHANGING REGULATIONS

The trekking regulations have been constantly modified over recent years, so you will need to check the latest changes when planning your trek. Information on the internet is often not up-to-date, so you will need to check in Kathmandu or Pokhara. Even as this guide was going to press, there was talk of changing the rules to require all independent trekkers to take a guide or porter. Further talks continue on this issue, but as yet no law has been passed. Such schemes (usually instigated by the big trekking outfits) have been imposed in the past, but subsequently abandoned with equal speed. Previous schemes actually harmed many small or fledgling local tourist operatives, porters and guides – particularly all those outside the Kathmandu valley. The reason cited for the latest changes is security – mainly because some individuals who trekked alone and off the main trails sadly came to grief. How these new regulations will affect trekking in Nepal is not clear. Information about the independent TIMs cards is also subject to change.

See also:

www.nepalimmigration.gov.np – immigration department for visa and permits

www.timsnepal.com – information on TIMS cards

www.taan.org.np – Trekking Agencies’ Association of Nepal

When to go

Dhaulagiri from a snowy Kopra Danda (Trek 4)

A trek anywhere in the Annapurna range is best undertaken in either autumn or spring. The autumn period, usually the most stable, is the optimum period for trekking in Nepal and will be the busiest time on the trails. Traditionally early October (after the monsoon) heralded the beginning of this season, but in recent years unsettled weather has prevailed. This has given rise to unseasonable rain, heavy cloud and delays for those flying to Jomsom. After mid-October the weather is usually better, with clearer skies and magical views. The harvest is underway, carpeting the hillsides with fabulous colours. November is often the clearest month, with crisp and clear days likely well into December. December is much colder at higher altitude, but trails are quieter. The stable conditions expected in autumn can occasionally be disrupted – about once every five years – when a storm blows in from the Bay of Bengal, wreaking havoc with heavy snow in the mountains.

Trekking through the winter is perfectly possible, but heading to high altitude during January and early February might mean encountering more cloud, snow and bitterly cold temperatures; minus 20°C has been recorded in Manang. Trekking into the Annapurna Sanctuary then can bring the risk of avalanche, so check locally with the lodges before proceeding up the Modi Khola. Crossing the Thorong La on the Circuit is also risky – heavy snow makes this dangerous, with a risk of avalanche even before the pass is reached.

The spring trekking season runs from late February to early May. The weather is generally stable, although clouds are likely to cover the mountains more often, and it will be hotter and quite muggy in the lower valleys. Haze is another factor for those who want their mountains crisp and clear for photography. Trekkers interested in flowering plants always favour the spring, when the rhododendrons and magnolia are spectacular. Wind tends to be a factor at this time of year, particularly closer to the Tibetan plateau, north of Manang or Muktinath.

Trekking at the height of summer, July and August, is not recommended and is totally frustrating for those hoping to see mountain vistas. Cloud, rain and snow can be expected at any time from mid-June to mid-September. The monsoon also brings landslides, leeches and flooding – so forget it, or keep to the lowest foothills around Pokhara.

OFFICIAL HOLIDAYS

1 January New Year

19 February Democracy Day

14 April Nepali New Year

23 April Democracy Day

1 May Labour Day

28 May Republic Day

There are also many other religious festive days.

For comprehensive listings see www.qppstudio.net and click on Nepal.

Style of trekking

Pony express: taking the deluxe option from Manang to the Thorong La (Trek 1)

The type of trek you are considering will dictate the itinerary. Very little of modern-day Nepal is wilderness. Trekking trails link the villages and are surprisingly busy; local porters, people off to markets, children scurrying about, dogs, monkeys, cows and trekkers all share these routes.

Fully supported group treks

For many this is the preferred option, providing maximum security for visitors. The tour operator removes many of the difficulties and discomforts associated with other ways of organising a trek. Visas and permits can be easily procured, transport does not have to be considered and all day-to-day logistics such as accommodation, food and carriage of baggage will be taken care of. Most trips will be fully inclusive, with few added extras. Clients can relax and admire the scenery around the Annapurnas in as much comfort as possible. Group treks utilise both lodge accommodation and tents; take your pick.

Note that there are some disadvantages to commercial group trekking. Large groups with the support of a Nepali crew have more impact on the local environment. Sometimes clients have to wait at camp for the gear to arrive, although lodges will be well stocked with drinks and refreshments. A major disadvantage is that there is less flexibility on a pre-organised itinerary. You may also be hiking with fellow trekkers who have underestimated the challenges and may not be in the best of spirits. In general, however, most hikers enjoy the conviviality of like-minded fellow walkers.

One other unnecessary danger is the possible effect of ‘peer pressure’ within the group. At its worst this can overrule common sense, with some members ignoring symptoms of altitude sickness in the unacknowledged race to compete. Do not fall into this lethal trap.

A typical group trekker’s day

The day begins at dawn for most trekkers, but fully supported walkers can expect a mug of tea and a bowl of hot water thrust through a tent flap or lodge doorway at around 6am. This is the wake-up call and means ‘get up now and pack your bags’. During breakfast, tents will be dismantled and the porter loads organised. Lodge trekkers can luxuriate in a warm dining area. Poor old campers will have to take the weather as it comes. With breakfast over and the loads packed, it’s off on the trail.

The morning walks tend to be a little longer to get the best of the morning’s clarity. Three to four hours is an average hiking period before lunch, including the odd tea stop along the way. Those on a lodge-based trek will find lunch ‘fooding’ easily on the main routes. Campers can slouch along until the kitchen boys and the cook come racing by to get ahead of the group to prepare lunch. It might be pancakes, bread or chips, tinned meat, fruit and other tasty goodies – probably a wider selection than available to the lodgers.

Afternoon walks are around three hours, although some days are inevitably longer because of the terrain. Campers should watch the kitchen boys and not get ahead of them. Afternoon tea and biscuits are served for campers (and group) lodgers on arrival at the night’s halt. Now is the time to read, rest or explore the locality. Dinner comes piping hot a little after sunset and may be a three-course delight. And that’s the day done for campers, bar crawling into that sleeping bag. Lodge guests can utilise the light, enjoying a beer or sampling the often dubiously produced local brews. (Be warned that so doing can adversely affect your health!) Take care with alcohol at altitude. It may be best to avoid it altogether.

Trek crews

Group trek porters in the rhododendron forest near Siklis (Trek 11)

Some of the following will also apply to small private groups and to independent trekkers hiring local staff. Normally the trek is led by a Nepalese guide who speaks good English and has done the trip many times before. Under him will be the most important member of the crew (not counting the cook): the Sirdar. His function (which can also be as leader/guide in a small group) is to organise all the porters, cooks and accompanying sherpas. With as many as 50 staff for a big camping group on a long trek, he certainly is a busy man. The cook naturally is in the spotlight; he will have several kitchen boys with him who will race ahead of the group to prepare lunch, afternoon tea and dinner. They carry all the cooking gear and often sing along the way.

In addition, there will be several sherpas. Some – although not all – may be from the Sherpa ethnic group who live in the Everest region. The term ‘sherpa’ in this context refers to the job of guiding the group, with one at the front and one bringing up the rear of the party. Big groups often have other sherpas floating between the front and rear guard. They also put up the dining tent and tents for the campers. Then there are the porters, as many as 30–40 for a large camping group. In such cases there will also be a Naiki (head porter), who takes some of the responsibilities from the Sirdar, organising and distributing the loads. The Naiki is often seen in the mornings adding items to a lighter load, causing some amusement and embarrassing the culprit who has offloaded a heavy bag on to a colleague in the hope of an easier day.

When booking a trek, be sure to check if all the food and meals are included. In recent years there has been a tendency for some companies to allow members on lodge treks to order and pay for all their own meals. This has happened because of the ever-rising costs in the mountains and because not including food appears to give a competitive edge in terms of the price of the trek. Do check this aspect of the ‘fully inclusive’ arrangement.

Independently organised trips

For those with more time, or who do not want to be locked into the group ethos, this is a good option, offering a great deal of freedom. Participants will be able to design and follow their own itinerary, according to their preferred length of trip and other special interests.

Organising a trip through an agent in the UK or Nepal for a couple or a small group is not necessarily more expensive than a group departure. Booking directly in Kathmandu is cheaper, but there is an increased risk because you will not be covered by any company liability if things go wrong. Be sure to have adequate insurance cover for helicopter rescue. These days there are a number of excellent local agents in Kathmandu who are very experienced in dealing with trekkers approaching them directly.

Contacting a local operator in Nepal is normally straightforward, although they might be unable to answer immediately at times because of regular, scheduled power cuts (known as load shedding). If you choose to arrange the trip with a Kathmandu agent, you can finalise the trip and pay the operators directly, but remember that if an internal flight is involved – to Jomsom for example – the agent might ask for some advance payment to cover that.

Independent trekking

Backpacking through Thonje kani (Trek 1)

This style is very popular with those able to carry their own equipment and seeking a closer, more intimate rapport with the local people. It’s also a cheaper way to trek in Nepal and ensures that your cash goes straight to the local people. Anyone willing to carry their own gear, with some experience of hill walking, can easily arrange a lodge-based trek on the main routes around the Annapurnas. If you have already been to Nepal or other developing countries you will have the added advantage of knowing roughly what to expect.

Many other trekkers in the Annapurna region hire a local porter/guide through a reputable agency, paying a wage that also covers all of their living expenses. If you hire a porter, make sure you check and provide all the necessary clothing and equipment for high altitude. In the past porters have died on high passes due to lack of proper equipment. Porters should also be insured – this should already be done if you hire a porter/guide through an agency. Hiring porters off the street and hotel areas is not necessarily a good idea these days, unless it comes through reliable recommendations.

If you decide to head off into the hills alone, be sure to read the sections in this guide on altitude and mountain safety. The points may seem obvious, but every year people are evacuated from or die in these mountains.

An independent trekker’s day

Being independent means you could have a long lie-in and make all those group people envious, but more likely you will want to be on the trail as early as possible. In the lodges you may be unlucky and find yourself at a disadvantage to the groups, who will often be served first. After breakfast the day is much the same as for those in groups, except that you can dictate your own pace, itinerary and lunch spots, so there are some positives against the negative of the heavy pack on your shoulders. Living off the lodges generally means a simple diet, but does that really matter? The lodges can supply all you really need in the way of sustenance. See Appendix E for details of foreign tour operators and local agencies.

‘FRIED CHAPS’

The Nepalis’ use of the English language is a most endearing feature of the country. You’ll see this most obviously on signboards advertising the lodges’ ‘faxsilities’, such as inside ‘to lets’, ‘toilet free rooms’ and, on enticing teahouse menus, ‘fried chaps’, ‘banana panick’ and the like. Watch out for the proudly displayed signs ‘Open defecation-free zone’.

Accommodation on trek

Mountains cannot provide bread and warmth, but they can provide secure anchorage for a troubled mind.

The Mountain Top, Frank S Smythe

Lodges

A trader’s house lodge in Tukuche (Trek 1)

The style and condition of accommodation used on trek will depend on the sort of trip chosen. In the past, camping throughout the Annapurnas was the best option, but today lodges are the more popular choice. Lodges en route are relatively basic, but dormitory-style rooms are rapidly being replaced by small but perfectly adequate twin-bedded rooms. Some rooms have en suite toilets and almost-warm showers. Beds tend to be hard, and dividing walls allow for a certain amount of communal interaction. Mattresses are getting thicker each year, so carrying a thermarest is not really necessary except on rare occasions (and for some homestays). There are now a few deluxe resort-style lodges in the Ghorepani/Ghandruk area, which are effectively ‘normal hotels’ with comfortable bedding, carpets and excellent dining areas.

Camping

Camping trekkers can expect a surprising degree of comfort in often wild, remote regions. Typically, large two-man tents are used and a mess tent is provided. In addition, dining tables, chairs, toilet tents and mattresses come as standard. All food is provided and cooked by the crews.

Homestay

Homestay is a new concept, where trekkers overnight in local people’s houses. Normally a room will be set aside for the guests. Most homestays are basic, with outside toilets and primitive washing facilities – much as the first trekkers found. Through local hydroelectric schemes electricity has now found its way to many rural areas, so lack of comfort is not quite on the scale it used to be. Mattresses may be thick or thin! Meals are provided by the household, using wholesome local produce. Don’t expect much other than nourishing dal bhat (lentils and rice) for dinner, but you could be surprised!

Washing

If there are no proper showers at a lodge you can ask for a bucket of hot water, but you’ll have to pay for it. Hot showers in lodges are generally provided by solar systems, but as with many aspects of trekking, utilising scarce resources (wood or kerosene) means conflict with conservation. Camping group trekkers will be given a bowl of hot water at some point during the day, normally mornings, and often now on arrival at camp as well.

Toilets

These will provide endless conversation throughout any trip. Most are outside, often up small, steep steps… be very careful not to drop any valuables down the holes! Increasingly however, loos are becoming quite modern, at least in appearance, with a few lodges offering ‘Flash Toilets’. Along the trails, toilet paper should be burnt and waste buried where possible.

Food

The kitchen of a lodge in Phu (Trek 6)

At one time a liking for dal bhat would have been a great advantage. Today eating on trek has become most civilised, with ample amounts and reasonable choice almost everywhere. Those on fully inclusive group or independently organised treks with full services can expect filling breakfasts, including porridge/cereal, bread/toast with eggs, as well as hot drinks. Lunch is often a substantial affair, with tinned meat, noodles, chips, cooked bread and something sweet to round off. At night the lodges are able to provide two- or three-course dinners: soup, noodles/pasta/rice/potatoes as well as a dessert of fruit and so on. Plentiful amounts of hot water/drinks are available on arrival and at all meal times to ensure dehydration is kept at bay, especially at higher altitudes. The further you get from civilisation, the less choice there is, but this far into the trek anything tastes good!

Kathmandu now has a good variety of supermarkets, but don’t anticipate many treats elsewhere. Across the city new shopping malls are opening, with familiar food brands and every possible item necessary for comfort. Pokhara Lakeside also has a good range of smaller supermarkets now. You might want to take some of your own supplies if venturing into remoter areas. Muesli tastes good even with water; instant soups and tinned fish are a good standby. Everyone should take chocolate, energy bars and snacks to relieve the eventual monotony of lodge food. Make sure as much indestructible rubbish is carried out by you or your crews, or use the places set aside for disposal.

IT’S BOILING!

Note that water only boils at 100°C at sea level, and the boiling temperature reduces by approximately 1°C for every 300m, meaning that your tea may not be as tasty nor the instant soups so scrumptious at Phu, 4100m above sea level. Thermometers were used by the early spies in the Himalayas to ascertain the altitude according to the temperature of their tea.

Money matters

The currency is the Nepalese Rupee (Rs). Notes come in the following denominations: Rs5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 and 1000, and coins: Rs1, 2 and 5.

APPROXIMATE EXCHANGE RATES

£1=Rs130

€1=Rs117

US$1=Rs107

CHF1=Rs108

Banks and ATMs

ATMs are now common in Kathmandu and Pokhara. In Thamel there is one in the Kathmandu Guest House courtyard. Larger sums can be taken from Nabil Bank ATMs. The Himalayan Bank is on Tri Devi Marg.