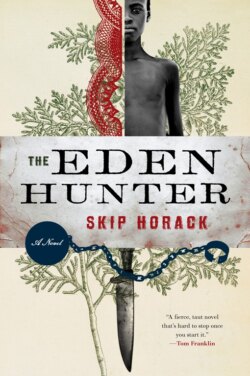

Читать книгу The Eden Hunter - Skip Horack - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеI

South—Into the forest—Lawson

KAU SAT CROSS-LEGGED in the shaky dugout, listening to the night sounds of the forest as the river carried him farther and farther south. In the distance he could hear the yips of red wolves coursing whitetails in the hot sandhills. A whippoorwill called and he tried to answer back. Five times he whistled before finally the notes came perfect and the whippoorwill called again.

The surface of the river was shining now, and at this first hint of dawn he paddled for the shore. He beached at a sandbar, then dragged the dugout into a thicket growing along the bank. The forest had grown quieter, and he squatted low in the underbrush, forcing himself to swallow some of the horse feed. In addition to the ten pounds of raw oats, the blanket and the saddlebags, all he had managed to pilfer was a dented canteen and a small tin pot—those and the blood-flecked hay hook. He checked the crocus sack that he had taken from the boy. Inside was a leather-sheathed hunting knife and a tinderbox, Benjamin’s sling and a collection of smooth stones that were each the size of chicken eggs. He added the knife and tinderbox to a saddlebag, then tossed the hay hook far out into the river. He waited for a splash but heard nothing.

Tears came as he ran his fingers along the leather sling—twin cords of finely plaited hemp joining a pocket of soft calfskin. This had been a gift from the innkeeper to his son, a weapon purchased from an Arab who did horse tricks in the Augusta circus. Kau dried his eyes against the calfskin and then folded the sling into one of the saddlebags. A distant wolf howled as he dropped ten of the round stones in with the horse feed.

He returned to the dim sandbar and found a pool of still water cut off from the muddy river. He went down on all fours and, careful not to silt the shallow pool, used his fingertips to brush the scum from its surface. A tear formed in the orange crust. He touched his dry lips to the tepid water and sucked long, steady streams down his chalked throat. He drank until his stomach felt heavy, then began spitting mouthfuls into the canteen.

The redbirds were singing as he walked back to the dugout. At Yellowhammer he had carved two short paddles from an oak plank. He took up one of them and scraped the sandy soil down to the hard-pan, forming a trench alongside the beached dugout. He settled into the crumbling furrow and from across the river came cackling and the beating of wings, a turkey dropping from its roost. The hen was yelping for her poults to join her when the day arrived clean and blue and Africa hot. Exhausted, he rolled the dugout over on top of him.

Flat on his back, hidden in the dark chamber, he pressed his head against the worn saddlebags. The turned earth was cool against his skin and the scent of the cut cypress worked to clear his mind. He closed his eyes and between flashes of the bloody boy was able to think and plan. When the innkeeper discovered them both missing, he would alert the American soldiers at the fort and send for the slavecatcher. Eventually there would be a chase and for that he needed to rest. He steadied his breathing and fought to collect himself.

LAWSON. THE SLAVECATCHER. The man lived in a cabin near the fort, alone save his mules and a pack of bloodhounds. Kau had seen him only once. A smuggler had a coffle of slaves camped near Yellowhammer when there was an escape. Lawson arrived and had the runaway treed in the river swamp within a few hours. The man was brought in lashed to the back of a black mule, and all gathered to witness his punishment. A coin from the smuggler and Lawson tied the runaway’s hands to the low-hanging branch of a live oak growing behind the inn, then hit him twenty times with a cat o’ nine he bragged as taken from a British tent at Cowpens.

Kau remembered the runaway’s skin tearing like wet paper and knew that with the boy dead he would receive much worse. Indeed, were the boy alive he could still turn back, sink the dugout and walk north to Yellowhammer. He could be asleep on his straw pallet before the sun broke the horizon. At breakfast he would tell Samuel he was sorry and they would go on about their day like nothing out of sort had ever happened between them. And when he saw the boy he would make things right there too, say I never really meant to run, and I thank you for not sayin nothin. I was gamblin that you wouldn’t never. You and the Marse are good to me here. Les never speak of this again.

But the boy, of course, was dead.

BY MIDDAY THE sun was full up and he was sweating in slick sheets. His filthy slave-clothes were soaked, and the pocket of air trapped beneath his dugout had gone sour. He was reminded of the burrow of the aardvark, the hold of the slave ship, and he suffered through the last long hours of the afternoon before the day finally gave way to night and it was safe for him to emerge.

One mosquito found him and then many more came. He shed his gray osnaburgs and ran barefoot across the sandbar into the water. Blood and salt washed from his skin as he bathed in the river, scouring himself with handfuls of sand. Along the opposite shore he saw a place where the current had carved into a soft hillside. He swam to the cutbank and broke free a slick knob of red clay, then returned to his campsite and dried himself with long moss pulled from the low branches of an oak. Bats flitted past as he smeared the whole of his body with the clay. Mosquitoes still pushed against him but now they were thwarted and flew off.

He removed the leather belt from his discarded pants and cinched it around his waist. The knife of the boy hung from its sheath at his side, and he used the blade to cut a long strip of rough osnaburg from his shirt, making a breechcloth that he tucked front and back through the buckled belt. He then shouldered the saddlebags, and while dragging the dugout back into the river he saw the reflection of a clay-man painted on the shimmering water. He bent over and studied his round face, the tight curls of hair caked with clay. He shut his eyes and then opened them. For the first time in well over five years he was looking at one of his people.

HIS SECOND NIGHT on the river. The moon had just begun its descent when he heard the riders, horses galloping south along the path that followed the western bank. He hunched forward in the dugout, and after the horses had continued on he paddled himself under a willow that was growing in a hard slant out over the water. There he kept hidden, waiting for the forest to settle behind the riders’ raging wake.

After that the riders came steadily. He set down his paddle and slid into the river. The water had cooled slightly with the night. He swam alongside the drifting dugout and stayed to the middle of the channel, his eyes level with the waterline as he searched for soldiers. Here and there sentinels stood solitary on the dark bank. He saw them and he thought of scarecrows.

FARTHER DOWNSTREAM THE dugout became wedged in a snag of dead and gnarled wood and he pulled it free. Soon the river narrowed, and along the bank he noticed a tiny ember glowing orange in the night—a sentinel smoking a cigar. Kau ducked even lower in the water, but still he feared that if he kept on he would be spotted. He kicked his legs and began towing the dugout to the upriver shore.

It was kill this man or leave the river, and as if to assign some meaning or purpose to the death of the boy, Kau decided that in this one moment he would not run. Instead, he pinned the dugout between cattails, then rose up carrying three pale stones and the sling of Abdullah the circus Arab.

The blue-coated sentinel stood on a gravel bank. Next to him a musket was propped against an ebony tangle of driftwood. Kau sat in the cattails and watched him. He and the boy had practiced with the sling most every day. Together they had learned to kill rats in the stables, hurl rocks a hundred yards distant. And now two separate lifetimes had funneled into this moment. That man would die or he would die. Maybe even the both of them.

He was choosing from among the sling-stones when he heard the fast clip of hooves approaching. The sentinel killed his cheroot as another soldier rode out onto the gravel. The rider was big and shadowy, and his mottled horse spun fully around as he called down to the sentinel. “Seen anything?” he asked.

“Nothing,” said the sentinel. “Any word of Benjamin?”

The rider shook his head. “But they put the whip to the other nigger. He thinks they might have done run off together, might be angling for Florida.”

“Why would Benjamin do a fool thing like that?”

“I bet that little ape witched him some way or another.”

The sentinel sent a flat rock skipping across the river. “Better not sail past here.”

“Just keep your head and mind what you’re shooting at. No holes in the boy.”

“Don’t be worrying about me.”

The rider slapped at a mosquito, and Kau heard the wet sound of flesh hitting flesh. “Ain’t nobody worried,” said the rider. “Just don’t make any mistakes.”

The rider galloped off and Kau stood. He was afraid but soon thoughts of the beaten Samuel focused him. He lifted the circus Arab’s sling from his neck, then slid the loop onto the middle finger of his right hand. The other sennit tapered into a braided knot that he placed between his thumb and forefinger. He slipped a stone into the cradle and stepped free of the cattails.

The sentinel had taken up his musket but was facing the river. Kau crept closer, slowly spinning the sling to better seat the stone. At ten paces he set his feet and then, uncoiling, he swung the sling hard overhead, the weight of the stone extending his arm. He released the knot and the stone launched, grazing the top of the sentinel’s high leather hat before it went careening off into the river. The struck man gave a surprised grunt and then whirled around. He was an older man, had a peppered beard. Kau flicked his wrist and the loose end of the sling snapped back into his hand. He loaded another stone, and the sentinel was struggling to full-cock his flintlock when Kau let fly again. This time the man was caught perfectly in the mouth, and there was the sound of teeth cracking. He dropped his musket and doubled over.

Kau ran forward, then picked up the musket and beat the stock into the man’s skull until he could see the soft sponge of brain in the moonlight. The body was twitching as Kau dragged it across the gravel. He concealed the corpse in the cattails and then turned for the dugout, the river.

THE DAY WAS breaking hot and humid as he followed an oxbow channel behind a sliver island. He had claimed the dead sentinel’s musket—that and his powderhorn, some patch and grease and ball. The boy had schooled him on firearms, and on hunting trips Kau had watched the innkeeper closely, memorizing the exact rhythms that went into loading a flintlock—the pour of the powder, the preparation of the ball, the priming of the flashpan. He examined the heavy musket as he drifted in the morning twilight. He had already learned their language, this was but another.

HE BEACHED AT a corner of the island—on a mud bank dimpled with the heart-shaped tracks of feral hogs—and was dragging the dugout ashore when he surprised a wallowing sounder of panther-scarred calicos. The wild hogs went crashing through the briers and then into the water, churning across the channel in a wrinkled line.

Later, collecting blackberries in a thicket, he was charged low and hard by a lone lingering sow. He dropped the musket and sprang for the rough trunk of a dogwood, pulling himself from the ground just as a torn ear grazed the bottom of his bare foot. The sow hit the still-bubbling water, and he eased down from his perch. Deeper in the thicket he found her abandoned farrow, eight slink piglets that were dead but not yet cold. He took one of the stillborn shoats back to the dugout, then ate great handfuls of acrid blackberries, translucent slices of raw white pork as succulent and tender as the flesh of some clear-water fish.

HE DREAMT OF the boy. A quick dream that came like a snakebite, a flash of heat lightning on the horizon. A brief vision of Benjamin tumbling along the river bottom, wispy threads of blood trailing him like smoke, his wet hair unraveled and in tendrils, gas bubbling from the holes in his small chest.

And then he awoke to a memory. Benjamin and the innkeeper are on horseback, quail hunting in the uplands, and he and Samuel follow in the wagon as lemon setters quarter off-cycle acres of lespedeza and ragweed. In a hayfield a young dog rouses a bedded spike buck, and the deer goes bouncing toward the hunters. The innkeeper dismounts and drops the buck with a close blast of fine-shot from his fowling piece. The boy cheers but then his father reloads and passes him the shotgun. “Once more,” says the innkeeper to his son. “In the head.” Benjamin takes the flintlock into his small and freckled hands, but then he hesitates as the buck drags its lifeless hindquarters across the field. Black hooves are stabbing black dirt when the bird dogs arrive. The snarling setters pile on to the wounded deer, and the angry innkeeper orders the boy not to fire. The spike buck is bleating like a fawn as Kau cuts its throat with the innkeeper’s knife. There is the metallic smell of blood, and Benjamin is told to remain with the wagon. “Ride with the niggers,” his father tells him, “ride with the niggers until you are ready to be a man.” The innkeeper canters off after his dogs and Benjamin weeps. Kau helps Samuel butcher the deer. “Don be cryin now,” says Samuel to the boy. “Killin ain’t no easy thing.” The boy says nothing, just climbs on to his horse and heads in the direction of Yellowhammer. Kau watches him leave, then wraps the slippery liver in a cut piece of hide. Crows caw as the distant pop of a shotgun announces that the innkeeper has scattered the morning’s first covey.

AT DARK CAME the chitter of coons night-fishing the shallows. He crawled out from under the dugout and the startled coons fled. A shooting star streaked across the southern sky and burned into nothing. It was time to move on.

HE WAS ALL night on the water before he rounded an elbow bend and saw the blockade. Two wide flatboats sat anchored across the river, the pine barges illuminated by the false-dawn glow of torches. Soldiers leapt from boat to boat, and in the center of the flotilla he saw the slavecatcher, Lawson, a leashed hound in either hand. Kau watched him and thought of a thing that Samuel would sometimes say when a bad man slunk past Yellowhammer.

That fella there be the Devil’s own pirate.

Kau backpaddled against the current, straining to avoid the place where the dark ended and light began. A dog barked but then went quiet. Kau made for the western shore, and he was guiding the dugout through a field of bone-smooth cypress knees when something hard and fast and hot tore across the slope of his shoulder. A musket boomed, and beneath a shoreline shower of flint-sparks and smoke stood a moonfaced soldier. Kau rolled into the water and unsheathed his knife. A great black cloud of mosquitoes lifted, and he was splashing toward the shore when the soldier threw down his spent musket. The man turned and ran in the direction of the downriver blockade. He was yelling in a high and winded voice, screaming, “Don’t shoot, it’s Jacob! He’s back there! He’s back there!”

There were constant hollers down the line as the soldier retreated. Kau grabbed the musket and saddlebags from the dugout, and a hunting horn sounded as he began moving away from the river.

HE WAS A quarter mile from the blockade when dawn burst and the hounds picked up his trail. He had already jettisoned the horse feed—the cooking pot as well—yet still they gained. He doubled back on a low ridge and inspected his shoulder. The musket ball had sliced a furrow through the caked clay, leaving a shallow red scrape but no real damage. He pressed clean green leaves against the cut and sat down with the musket. If they were trying to kill him then they must have found the body of the sentinel, maybe even the sunken boy. He lifted the frizzen to check the prime on the flashpan. The powder looked dry but he added a little more from the powderhorn. The hounds would be ariving soon. He laid the musket across the front of his breechcloth and he waited.

IN THE GRAY light he saw the blurred mass of the main pack pour into the draw beneath him. They continued on, then were followed in a short while by a bell-mouthed bitch—pregnant, her teats heavy with milk—carefully working the scent with an occasional bawl. The old slavehound was nosing through the dry leaves when she came to a stop. She sat on her haunches with her head tilted, and then Kau whistled low and she let loose a howling bay, long and deep. He knelt on the ridge, cocking back the hammer of the musket as she came in a lumber. The bellowing hound was almost to him when he thrust the musket forward and pulled the trigger. The flashpan hissed before finally the muzzle load caught. There was an explosion and then a sharp, quick yelp. He opened his eyes and saw the hound sliding slowly down the hill, her frothing jaws clicking so that for a moment she looked like some enormous dying insect.

The main pack went silent at the shot, and he pulled the powderhorn from a saddlebag and began reloading the musket—a four-count measure of powder, a ball wrapped in a greased patch of cloth and fitted into the muzzle. He pushed the ramrod down the barrel and was priming the flashpan when the hounds started up again. They were moving west still, staying true to the trail he had laid, and this helped to settle him. He tucked the powderhorn through his belt and stood, shouldering his saddlebags as he started out in a straight southern jog.

The hunting horn sounded, but the hounds were overeager and refused to quit the hot trail. Twice more Lawson tried to call in his dogs to check their pursuit. Each time they ignored the slavecatcher’s horn. Kau pushed forward, running, and soon the river-bottom graywoods rose into green pinewoods as the whole of the morning sun emerged in the golden east.

IN A SKELETON forest of fire-scarred pine he stopped again. A lightning-struck longleaf had snapped near its base, and he crawled carefully atop that jagged and oozing pedestal. Behind him he could see quick streaks of hide as the hounds came like monkeys moving through a canopy. He pinned his saddlebags between his feet and waited.

Before long five hounds had collected at the burnt and broken stump, clawing at pine bark as they tried to reach him. He shot a young male point-blank in the chest, then pulled patch and ball from a saddlebag and reloaded as quickly as he could manage. Another point-blank shot and Lawson began to scream. Kau could hear him clearly now. “Where the hell are you?” the slavecatcher hollered. “I’m a-coming, nigger.”

Kau fired again, and the surviving pair of hounds skulked off whimpering and ruined just as the slavecatcher appeared in his torn buckskins. He was tall and thin and bearded, had black hair veined with gray. Lawson saw the three dogs lying dead at the foot of the broken pine and hurried forward in a hunched trot. At thirty yards the exhausted man raised his longrifle, the black barrel cutting small circles as he tried to take aim. Kau finished seating another ball, then waved the ramrod in the air as he spoke out across the distance between them. “Lemme alone,” he said. “You miss and I’m gonna kill you.”

“So it talks,” said the slavecatcher.

Lawson rushed his shot and there came the hollow echo-knock of a lead ball burying itself into a faraway tree. Kau leapt from his pine stump and the slavecatcher turned to run. The two remaining hounds shied as Kau pursued their master. He primed the musket’s flashpan on the sprint, then let the powderhorn fall to the ground. At an arm’s length he shot Lawson low in the back, the barrel so close that for a moment the man’s greasy buckskins caught fire. The slavecatcher collapsed, gutshot and smoking, and Kau came sliding down beside him.

Lawson’s pink stomach was split across the middle and showing cords of intestine. His mouth cracked open. Two of his front teeth were missing. “Well, you’ve gone and done it,” he whispered. “Done what the lobsterbacks never could.”

Kau ran his fingers over the stock of Lawson’s longrifle. There were stripes and curls in the amber wood. “I gave you a good choice in this,” he said.

“Turning tail from some rag-wearing nigger wasn’t no choice.”

“You done ran though.”

Lawson called for the two hounds but they stayed huddled together and frightened among the already dead. Kau watched them and thought of the calmed lions in one of Samuel’s Bible stories. Lawson cursed the dogs and then he cursed him. “You son of a bitch,” he said. The slavecatcher coughed and a trickle of blood escaped the corner of his scabbed mouth. He started to shiver. Sweat had pooled in the hairless hollow of his chin.

Kau touched him on the shoulder. “I can go and cut your throat if you want that.”

“Well,” said Lawson. “I don’t.”

“Be a long while fore they findin you.”

“I ain’t afraid.”

“You gonna be. At the end.”

Lawson spit blood at him but missed. “What I might fear ain’t no concern of yours.”

Kau nodded and the two of them sat there in silence, thinking. A fox squirrel chattered as he unsheathed his knife. He had realized something. “I should scalp you,” he said.

“Now why?”

“Them soldiers maybe go thinkin redsticks about.” Kau moved closer. “Lose they heart for chasin me.”

The slavecatcher sighed a scratched breath. “Play Indian with your possum teeth. I ain’t gonna die begging.”

“I’ll kill you fore I do it.”

“Well, thank the good Jesus for that.” Lawson sneered and then spit more bright blood. “You kill that boy?”

Kau looked up, searching the blackened forest for danger. “Not wantin to.”

The slavecatcher repeated the words, mocking the thickness of his accent. “Ain’t what I asked,” he said.

“You go and whip my friend?”

Lawson nodded and Kau smelled shit, piss. “I was a scout for Marion, spied with my own eyes that British bastard Tarleton making a Patriot widow dig up her dead husband.” The slavecatcher shook his head. “Least that was a war.”

“That means you ready?”

“Don’t mean that at all.”

“You won’t feel nothin.”

The slavecatcher laughed a high chopping laugh, and a red mist sprayed from his mouth. “Get on,” he said. “This has become an ugly world.”

Kau pressed the blade against the loose and wrinkled skin folded across Lawson’s throat. “I know that,” he said.

“Well, then you go on and live free in it awhile,” said the slavecatcher. “See if it treats you any better now.”