Читать книгу What Does Europe Want? The Union and its Discontents - Slavoj Žižek - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

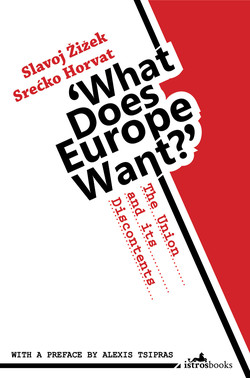

ОглавлениеWHAT DOES EUROPE WANT?

WHAT DOES EUROPE WANT?

The Union and its Discontents

SLAVOJ ŽIŽEK

SREĆKO HORVAT

First published in 2013 by

Istros Books

London, United Kingdom

www.istrosbooks.com

© Slavoj Žižek, 2013

© Srećko Horvat, 2013

Artwork & Design © Milos Miljkovich, 2013

Graphic Designer/Web Developer – miljkovicmisa@gmail.com

Typeset by Octavo-Smith Ltd

The right of Srećko Horvat and Slavoj Žižek to be identified as the authors of their respective works has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

ISBN: 978-1908236166 (print edition)

ISBN: 9781908236845 (eBook)

Printed in England by

CMP (UK), Poole, Dorset

www.cmp-uk.com

This edition has been made possible through the financial support granted by the Croatian Ministry of Culture.

CONTENTS

Foreword Alexis TsiprasThe Destruction of Greece as a Model for All of Europe. Is this the Future that Europe Deserves?

1. S. Žižek Breaking Our Eggs without the Omelette, from Cyprus to Greece.

2. S. Horvat Danke Deutschland!

3. S. Žižek When the Blind Are Leading the Blind, Democracy Is the Victim

4. S. Horvat Why the EU Needs Croatia More than Croatia Needs the EU

5. S. Žižek What Does Europe Want?

6. S. Horvat Are the Nazis Living on the Moon?

7. S. Žižek The Return of the Christian-conservative Revolution

8. S. Horvat In the Land of Blood and Money: Angelina Jolie and the Balkans

9. S. Žižek The Turkish March

10. S. Horvat: War and Peace in Europe: ‘Bei den Sorglosen’

11. S. Žižek Save Us from the Saviours: Europe and the Greeks

12. S. Horvat: ‘I’m Not Racist, but … The Blacks are Coming!’

13. S. Žižek Shoplifters of the World Unite

14. S. Horvat Do Markets Have Feelings?

15. S. Žižek The Courage to Cancel the Debt

16. S. Horvat The Easiest Way to the Gulag Is to Joke About the Gulag

17. S. Žižek We Need a Margaret Thatcher of the Left

18. A. Tsipras Europe Will Be Either Democratic and Social or It Will No Longer Exist (interview)

19. S. Žižek and A. Tsipras ‘The Role of the European Left’ (debate)

Notes

Alexis Tsipras

FOREWORD: THE DESTRUCTION OF GREECE AS A MODEL FOR ALL OF EUROPE.

IS THIS THE FUTURE THAT EUROPE DESERVES?

From the middle of the 1990s until almost the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, Greece tended towards economic growth. The main characteristics of that growth were the very large and non-taxed profits enjoyed by the rich, along with over-indebtedness and the rising unemployment among the poor. Public money was stolen in numerous ways, and the economy was limited mainly to the consumption of imported goods from rich European countries. Rating agencies considered this model of ‘cheap money, cheap labour’ the model of dynamic emerging economies.

The Vicious Cycle of Depression

Everything, however, changed after the 2008 crisis. The cost of the bank losses that were created by uncontrolled speculation were transfered to national governments, which were in turn transferred to society at large. The flawed model of Greek development collapsed and the country was deprived of the opportunity to borrow, causing it to become dependent on the IMF and the European bank. And all this was accompanied by an extremely severe austerity programme.

This programme, which the Greek government adopted without proper debate, consists of two parts: ‘stabilisation’ and ‘reform’. The conditions of the programme are presented as positive, in order to cover up the huge social destruction it has caused. In Greece, the part of the programme named ‘stabilisation’ leads to indirect, destructive taxation, large cuts in public spending and the destruction of the welfare state, especially in the areas of health, education and social security, as well as the privatisation of basic social goods, such as water and energy. The programme which forms part of the ‘reform’ deals with the simplification of redundancy procedure, the elimination of collective agreements and the creation of ‘special economic zones’. This is accompanied by many other regulations designed to facilitate the investment of powerful and colonialist economic forces, without the inconvenience of, say, having to go all the way to South Sudan. These are just some of the conditions that are in the ‘Memorandum’, the contract that was signed by Greece with the IMF, the European Union and the European Central Bank.

These measures are naturally supposed to lead Greece out of the crisis. The strict ‘stabilisation’ programme should lead to budget surpluses, allowing the country to stop borrowing, while at the same time enabling it to pay off the debt. On the other hand, the ‘reforms’ are aimed at regaining market confidence, encouraging them to invest after witnessing the destroyed welfare state and the desperate, insecure and low-paid workers in the labour market. This would lead to new ‘development’; something which does not exist anywhere except in ‘holy books’ and the perverted minds of global neoliberalism.

It was assumed that the programme would be very effective and fast, and that Greece would soon be ‘reborn’ and back on the path of growth. But three years after the signing of the ‘Memorandum’, the situation is becoming worse. The economy is sinking further, and the taxes are obviously not collected, for the simple reason that the Greek citizens are unable to pay them. The reduction of spending has now reached the core of social integrity, creating the conditions of a humanitarian crisis. In other words, we are now talking about people who are reduced to eating rubbish and sleeping on the pavements, about pensioners who can not afford to buy bread, of households without electricity, of patients who are unable to afford medicine and treatment. And all this within the eurozone.

Investors, of course, do not come, given that the current bankruptcy option remains open. And of course, the authors of the ‘Memorandum’ after each tragic failure, react by imposing more taxes and more cuts. The Greek economy has entered a vicious cycle of uncontrolled depression that leads nowhere except to complete disaster.

Taliban Neoliberalism

The Greek ‘rescue’ plan (another convenient term used to describe this disaster) ignores a fundamental principle. The economy is like a cow: it eats grass and produces milk. It is inconceivable to take away a quarter of her grass and expect her to produce four times more milk. The cow will simply die. The same is now happening to the Greek economy.

The Greek Left realised, from the very first moment, that the austerity measures would not ‘cure’, but actually deepen the crisis. When someone is drowning, he needs to be thrown a lifeline, not a weight. For their part, the Taliban neoliberalists still assure us that things will improve. Yet even the most stupid among them must now know that this is a lie. But this stance is not nonsense, and it’s not dogmatism. The leaders of the IMF themselves recently stated that there is an error in the design of the Greek austerity programme, which is doomed to failure, and that the effects of the recession are completely out of control. And yet the programme continues with an unprecedented stubbornness and persistence, and the situation is becoming more and more difficult. The conclusion can only be that something else lies behind all this.

In fact, behind all this is the fact that pulling the Greek economy out of the crisis is not in the interests of Europe or the IMF. Much more important is the desire to remove, as the ultimate goal of the programme, what in post-war Europe became known as the ‘social contract’. The fact that Greece will be left bankrupt and riddled with social problems is not important. What is important, is that a eurozone country is openly discussing the introduction of a wage level comparative to that of the Chinese, along with the abolition of workers’ rights, the abolition of national insurance and the welfare state, and the total privatisation of utilities and public goods. Those neoliberal depraved minds, who already encountered violent resistance in European societies following the decade of the 1990s, now find their dream becoming a reality through the pretext of the crisis.

Greece is the first step. The debt crisis has already spread to other countries in southern Europe, and penetrates deeper into the heart of the European Union. Greece can serve as a case study. Anyone who is exposed to the speculative attacks of the markets has no other choice but to destroy the remnants of the welfare state, as has happened in Greece. Similar memoranda in Spain and Portugal have already introduced similar changes. But this strategy is fully revealed in the ‘European Pact for Stability’, which promotes Germany in place of the entire Union. Member states are no longer free to manage their own finances. The central institutions of the EU are allowed to intervene in budgets and impose tough fiscal measures to reduce deficits. This policy strongly affects schools, nurseries, universities, public hospitals and social programmes. If people use democracy as a defence against austerity, as happened recently in Italy, the result for democracy is even worse.

There Are Alternatives

Let us be clear: the generalised European model was not created in order to save Greece, but to destroy it. Europe’s future is already planned and it envisages happy bankers and unhappy societies. In the anticipated development plan, capital will be the rider and society will be the horse. It’s an ambitious plan, but it can not go far. The reason is that not one such project was ever completed without the consensus of society and the protection of its most vulnerable. It seems that the leading European elite has currently forgotten this fact. Unfortunately for them, they will have to face up to it sooner than they think.

It is the beginning of the end of the existing neoliberal capitalism; the most aggressive capitalism that mankind has ever faced, and which has dominated for the past two decades. Ever since the collapse of Lehman Brothers, there have been two conflicting strategies for overcoming the crisis which represent two different perspectives on the world economy. The first strategy is a financial expansion, with the printing of new money, the nationalisation of banks and the increased taxation of the rich. The other is by saving, transferring the bank debt to the public sector debt, relying on the middle and lower classes of society being overly taxed, while only the rich can avoid tax altogether. European leaders choose another model, but they too have come to a standstill, while facing additional problems. These problems led to an historic conflict in Europe. A conflict that seemingly has geographical dimensions and designations: on the surface it seems to be divided into that of north-south, yet beneath the surface there is a class conflict that relates to two conflicting strategies for Europe. One strategy defends the complete domination of capital, unconditionally and without principles, and without any plan for secure social cohesion and welfare. The other strategy defends European democracy and social needs. The conflict has already begun.

There is an alternative solution to the crisis. This is to protect European companies from the speculation of financial capital. It is the emancipation of the real economy from the constraints of profit. It is a way out of monetarism and authoritative fiscal policy. It is a new development planning with social benefits as the main criterion. It is a new production model, based on decent work conditions, the expansion of public good and environmental protection. This view is consistently left out of the discussion by the European leadership. It remains with the people, the European workers and already ‘bitter’ movements to strike their own stamp on history and prevent the mass looting and destruction.

The experience of previous years leads to one conclusion: there is one morality in politics and another for economy. In the years since 1989, the morality of the economy has fully prevailed over the ethics of politics and democracy. What went in favour of the two, those five or ten strong financial institutions, were considered legitimate, even if it would be contrary to fundamental human rights principles. Today our task is to restore the dominance of political and social moral values, as opposed to the logic of profit.

The War of Resistance

How will we make the dynamics of social struggle work? And how can we break, once and for all, the harness of social apathy on which the construction of Europe since 1989 is founded upon? The active participation of the masses in politics is the only thing that can frighten the ruling elite in Europe and worldwide. And that’s exactly why we should make it happen.

The plan for a stronger economic cycle is clear. We need to create a different political and social project and defend it by all means at the central and local level. Let’s start with the workplace, with universities and neighbourhoods, until we have a coordinated joint action in all European countries. It is a struggle of resistance that will result in a victory as long as it leads to a common alternative programme for Europe. Today’s conflict is not one between deficit and surplus countries, or between disciplined and restless people. Today’s conflict is between the European social interests and the needs of capital for continual profit growth.

We will defend social interests, or else our future and our children’s future will be uncertain and dark, something that in recent decades we could not even imagine. The model for development that was based on the ‘free market’ is now bankrupt. At this time the dominant forces are attacking society, its unity and all the privileges that it has managed to retain. This is what is happening in Greece, and this is the plan for the whole of Europe. Let us therefore defend ourselves by any means. We must support a social resistance that invokes and permanently upholds a sense of solidarity and a unified strategy for the peoples of Europe.

The future does not belong to neoliberalism, bankers and a few powerful multinational companies. The future belongs to the nation and to society. It’s time to open the way for a democratic, socially cohesive and free Europe. Because this is the only viable, realistic and feasible solution to exit the current crisis.

Greece

March 2013

Slavoj Žižek

1 BREAKING OUR EGGS WITHOUT THE OMELETTE, FROM CYPRUS TO GREECE

There is a story (apocryphal, maybe) about the Left-leaning, Keynesian economist, John Galbraith: before a trip to the USSR in the late 1950s, he wrote to his anti-communist friend Sidney Hook: ‘Don’t worry, I will not be seduced by the Soviets and return home claiming they have socialism!’ Hook answered him promptly: ‘But that’s what worries me – that you will return claiming that the USSR is NOT socialist!’ What worried Hook was the naive defence of the purity of the concept: if things go wrong with building a Socialist society, this does not invalidate the idea itself, it just means we didn’t implement it properly.

Do we not detect the same naivety in today’s market fundamentalists? When, during a recent TV debate in France, Guy Sorman claimed that democracy and capitalism necessarily go together, I couldn’t resist asking him the obvious question: ‘But what about China today?’ He snapped back: ‘In China there is no capitalism!’ For a fanatically pro-capitalist Sorman, if a country is non-democratic, it simply means it is not truly capitalist but practises its disfigured version, in exactly the same way that for a democratic communist, Stalinism was simply not an authentic form of communism.

The underlying mistake is not difficult to identify – it is the same as in the well-known joke: ‘My fiancée is never late for an appointment; because the moment she is late she is no longer my fiancée!’ This is how today’s apologist of the market, in an unheard-of ideological kidnapping, explains the crisis of 2008: it was not the failure of the free market which caused it but the excessive state regulation, i.e. the fact that our market economy was not a true one, that it was still in the clutches of the welfare state. When we stick to such a purity of market capitalism, dismissing its failures as accidental mishaps, we end up in a naive progressivism whose exemplary case is the Christmas issue of The Spectator magazine (15 December 2012). It opens up with the editorial ‘Why 2012 was the best year ever’, which argues against the perception that we live in ‘a dangerous, cruel world where things are bad and getting worse’. Here is the opening paragraph:

It may not feel like it, but 2012 has been the greatest year in the history of the world. That sounds like an extravagant claim, but it is borne out by evidence. Never has there been less hunger, less disease or more prosperity. The West remains in the economic doldrums, but most developing countries are charging ahead, and people are being lifted out of poverty at the fastest rate ever recorded. The death toll inflicted by war and natural disasters is also mercifully low. We are living in a golden age.1

The same idea was developed in detail by Matt Ridley. Here is the blurb for his The Rational Optimist:

A counterblast to the prevailing pessimism of our age, and proves, however much we like to think to the contrary, that things are getting better. Over 10,000 years ago there were fewer than 10 million people on the planet. Today there are more than 6 billion, 99 per cent of whom are better fed, better sheltered, better entertained and better protected against disease than their Stone Age ancestors. The availability of almost everything a person could want or need has been going erratically upwards for 10,000 years and has rapidly accelerated over the last 200 years: calories; vitamins; clean water; machines; privacy; the means to travel faster than we can run, and the ability to communicate over longer distances than we can shout. Yet, bizarrely, however much things improve from the way they were before, people still cling to the belief that the future will be nothing but disastrous.2

And there is more of the same. Here is the blurb for Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature:

Believe it or not, today we may be living in the most peaceful moment in our species’ existence. In his gripping and controversial new work, New York Times bestselling author Steven Pinker shows that despite the ceaseless news about war, crime, and terrorism, violence has actually been in decline over long stretches of history. Exploding myths about humankind’s inherent violence and the curse of modernity, this ambitious book continues Pinker’s exploration of the essence of human nature, mixing psychology and history to provide a remarkable picture of an increasingly enlightened world.3

With many provisos, one can roughly accept the data to which these ‘rationalists’ refer – yes, today we definitely live better than our ancestors did 10,000 years ago in the Stone Age, and even an average prisoner in Dachau (the Nazi working camp, not in Auschwitz, the killing camp) was living at least marginally better than, probably, a slave prisoner of the Mongols. Etc. etc. – but there is something that this story misses.

There is a more down-to-earth version of the same insight which one often hears in mass media, in the quoted passage from The Spectator but especially those of non-European countries: crisis? What crisis? Look at the BRIC countries, at Poland, South Korea, Singapore, Peru, even many sub-Saharan African states – they are all progressing. The losers are only Western Europe and, up to a point, the US, so we are not dealing with a global crisis, but just with the shift of the dynamics of progress away from the West. Is a portent symbol of this shift not the fact that, recently, many people from Portugal, a country in deep crisis, are returning to Mozambique and Angola, ex-colonies of Portugal, but this time as economic immigrants, not as colonisers? So what if our much-decried crisis is a mere local crisis in an overall progress? Even with regard to human rights: is the situation in China and Russia now not better than fifty years ago? Decrying the ongoing crisis as a global phenomenon is thus a typical Eurocentrist view, and a view coming from Leftists who usually pride themselves on their anti-Eurocentrism.

But we should restrain our anti-colonialist joy here – the question to be raised is: if Europe is in gradual decay, what is replacing its hegemony? The answer is: ‘capitalism with Asian values’ – which, of course, has nothing to do with Asian people and everything to do with the clear and present tendency of contemporary capitalism, as such, to suspend democracy. From Marx on, the truly radical Left was never simply ‘progressivist’ – it was always obsessed by the question: what is the price of progress? Marx was fascinated by capitalism, by the unheard-of productivity it unleashed; he just insisted that this very success engenders antagonisms. And we should do the same with today’s progress of global capitalism: keep in view its dark underside which is fomenting revolts.

People rebel not when ‘things are really bad’, but when their expectations are disappointed. The French Revolution occurred after the king and the nobles were for decades gradually losing their full hold on power; the 1956 anti-communist revolt in Hungary exploded after Nagy Imre had already been prime minister for two years, after (relatively) free debates among intellectuals; people rebelled in Egypt in 2011 because there was some economic progress under Mubarak, giving rise to a whole class of educated young people who participated in the universal digital culture. And this is why the Chinese communists are right to panic, precisely because, on average, the Chinese are now living considerably better than forty years ago – but the social antagonisms (between the newly rich and the rest) exploded, plus expectations are much higher. That’s the problem with development and progress: they are always uneven, they give birth to new instabilities and antagonisms, and they generate new expectations which cannot be met. In Tunisia or Egypt just prior to the Arab Spring, the majority probably lived a little bit better than decades ago, but the standards by which they measured their (dis)satisfaction were much higher.

So yes, The Spectator, Ridley, Pinker etc. are in principle right, but the very facts that they emphasise are creating conditions for revolt and rebellion. Recall the classic cartoon scene of a cat who simply continues to walk over the edge of the precipice, ignoring that she no longer has ground under her feet – she falls down only when she looks down and notices she is hanging in the abyss. Is this not how ordinary people in Cyprus must feel these days? They are aware that Cyprus will never be the same, that there is a catastrophic fall in the standard of living ahead, but the full impact of this fall is not yet properly felt, so for a short period they can afford to go on with their normal daily lives like the cat who calmly walks in the empty air. And we should not condemn them: such delaying of the full crash is also a surviving strategy – the real impact will come silently when the panic will be over. This is why it is now, when the Cyprus crisis has largely disappeared from the media, that one should think and write about it.

There is a well-known joke from the last decade of the Soviet Union about Rabinovitch, a Jew who wants to emigrate. The bureaucrat at the emigration office asks him why, and Rabinovitch answers: ‘There are two reasons why. The first is that I’m afraid that in the Soviet Union the communists will lose power, and the new power will put all the blame for the communist crimes on us Jews – there will again be anti-Jewish pogroms …’ The bureaucrat interrupts him: ‘But this is pure nonsense. Nothing can change in the Soviet Union; the power of the communists will last forever!’ Rabinovitch responds calmly: ‘Well, that’s my second reason.’

It is easy to imagine a similar conversation between a European Union financial administrator and a Cypriote Rabinovitch today – Rabinovitch complains: ‘There are two reasons we are in a panic here. First, we are afraid that the EU will simply abandon Cyprus and let our economy collapse …’ The EU administrator interrupts him: ‘But you can trust us, we will not abandon you, we will tightly control you and advise you what to do!’ Rabinovitch responds calmly: ‘Well, that’s my second reason.’

Such a deadlock effectively renders the core of the sad predicament of Cyprus: it cannot survive in prosperity without Europe, but also not with Europe – both options are worse, as Stalin would have put it. Recall the cruel joke from Lubitsch’s film To Be or Not to Be: when asked about the German concentration camps in occupied Poland, responsible Nazi officer ‘Concentration Camp Ehrhardt’ snaps back: ‘We do the concentrating, and the Poles do the camping.’ Does the same not hold for the ongoing financial crisis in Europe? The strong Northern Europe, focused in Germany, does the concentrating, while the weakened and vulnerable South does the camping. What is emerging on the horizon are thus the contours of a divided Europe: its Southern part will be more and more reduced to a zone with a cheaper labour force, outside the safety network of the welfare state, a domain appropriate for outsourcing and tourism. In short, the gap between the developed world and those lagging behind will now run within Europe itself.

This gap is reflected in the two main stories about Cyprus which resemble the two earlier stories about Greece. There is what can be called the German story: free spending, debts and money laundering cannot go on indefinitely, etc. And there is the Cyprus story: the brutal EU measures amount to a new German occupation which is depriving Cyprus of its sovereignty. Both stories are wrong, and the demands they imply are nonsensical: Cyprus by definition cannot repay its debt, while Germany and the EU cannot simply go on throwing money to fill in the Cypriot financial hole. Both stories obfuscate the key fact: that there is something wrong with the entire system in which uncontrollable banking speculations can cause a whole country to go bankrupt. The Cyprus crisis is not a storm in the cup of a small marginal country; it is a symptom of what is wrong with the entire EU system.

This is why the solution is not just more regulation to prevent money laundering etc., but (at least) a radical change in the entire banking system – to say the unsayable, some kind of socialisation of banks. The lesson to be taken from the crashes that accumulated worldwide from 2008 on (Wall Street, Iceland …) is clear: the whole network of financial funds and transactions, from individual deposits and retirement funds up to the functioning of all kinds of derivatives, will have to be somehow put under social control, streamlined and regulated. This may sound utopian, but the true utopia is the notion that we can somehow survive with small cosmetic changes.

But there is a fatal trap to be avoided here: the socialisation of banks that is needed is not a compromise between wage labour and productive capital against the power of finance. Financial meltdowns and crises are obvious reminders that the circulation of capital is not a closed loop which can fully sustain itself, i.e., that this circulation points towards the reality of producing and selling actual goods that satisfy actual people’s needs. However, the more subtle lesson of crises and meltdowns is that there is no return to this reality – all the rhetoric of ‘let us move from the virtual space of financial speculations back to real people who produce and consume’ is deeply misleading; it is ideology at its purest. The paradox of capitalism is that you cannot throw out the dirty water of financial speculations and keep the healthy baby of real economy: the dirty water effectively is the ‘bloodline’ of the healthy baby.

What this simply means is that the solution of the Cyprus crisis does not reside in Cyprus. For Cyprus to get a chance, something will have to change elsewhere. Otherwise we will all remain caught in the madness that distorts our behaviour in times of crises. Here is how Marx defines the traditional miser as ‘a capitalist gone mad’, hoarding his treasure in a secret hideout, in contrast to the ‘normal’ capitalist who augments his treasure by throwing it into circulation4:

The restless never-ending process of profit-making alone is what he aims at. This boundless greed after riches, this passionate chase after exchange-value, is common to the capitalist and the miser; but while the miser is merely a capitalist gone mad, the capitalist is a rational miser. The never-ending augmentation of exchange-value, which the miser strives after, by seeking to save his money from circulation, is attained by the more acute capitalist, by constantly throwing it afresh into circulation.

This madness of the miser is nonetheless not something which simply disappears with the rise of ‘normal’ capitalism, or its pathological deviation. It is rather inherent to it: the miser has his moment of triumph in the economic crisis. In a crisis, it is not – as one would expect – money which loses its value, and we have to resort to the ‘real’ value of commodities; commodities themselves (the embodiment of ‘real /use/ value’) become useless, because there is no-one to buy them. In a crisis, ‘money suddenly and immediately changes from its merely nominal shape, money of account, into hard cash. Profane commodities can no longer replace it. The use-value of commodities becomes value-less, and their value vanishes in the face of their own form of value. The bourgeois, drunk with prosperity and arrogantly certain of itself, has just declared that money is a purely imaginary creation. ‘Commodities alone are money,’ it said. But now the opposite cry resounds over the markets of the world: only money is a commodity … ‘In a crisis, the antithesis between commodities and their value-form, money, is raised to the level of an absolute contradiction.’5

Does this not mean that at this moment, far from disintegrating, fetishism is fully asserted in its direct madness? In crisis, the underlying belief, disavowed and just practised, is thus directly asserted. And the same holds for today’s ongoing crisis: one of the spontaneous reactions to it is to turn to some commonsense guideline: ‘Debts have to be paid!’, ‘You cannot spend more than you produced!’, or something similar – and this, of course, is the worst thing one can do, since in this way, one gets caught in a downward spiral. First, such elementary wisdom is simply wrong – the United States was doing quite well for decades spending much more than it produced.

At a more fundamental level, we should clearly perceive the paradox of debt: at the direct material level of social totality, debts are in a way irrelevant, inexistent even, since humanity as a whole consumes what it produces – by definition, one cannot consume more. One can reasonably speak of debt only with regard to natural resources (destroying the material conditions for the survival of future generations), where we are indebted to future generations which, precisely, do not yet exist and which, not without irony, will come to exist only through – and thus be indebted for their existence to – ourselves. So here also, the term ‘debt’ has no literal sense, it cannot be ‘financialised’, quantified into an amount of money. The debt we can talk about occurs when, within a global society, some group (nation or whichever) consumes more than it produces, which means that another group has to consume less than it produces – but here, relations are not as simple and clear as it may appear. Relations would be clear if, in a situation of debt, money would just have been a neutral instrument measuring how much more one group consumed with regard to what it produced, and at whose expense – but the actual situation is far from this. According to public data, around 90 per cent of money circulating around is the virtual credit money; so if ‘real’ producers find themselves indebted to financial institutions, one has good reason to doubt the status of their debt – how much of it was the result of speculations which happened in a sphere without any link to the reality of a local unit of production?

So when a country finds itself under the pressure of international financial institutions, be it IMF or private banks, one should always bear in mind that their pressure (translated into concrete demands: reduce public spending by dismantling parts of the welfare state, privatise, open up your market, deregulate your banks …) is not the expression of some neutral objective, logic or knowledge, but of a doubly partial (‘interested’) knowledge: at the formal level, it is a knowledge which embodies a series of neoliberal presuppositions, while at the level of content, it privileges the interests of certain states or institutions (banks etc.).

When the Turkish communist writer Panait Istrati visited the Soviet Union in the mid-1930s, the time of the big purges and show trials, a Soviet apologist trying to convince him about the need of violence against the enemies evoked the proverb, ‘You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs’, to which Istrati tersely replied, ‘All right. I can see the broken eggs. Where’s this omelette of yours?’ But we should say the same about the austerity measures imposed by the IMF: the Greeks would have the full right to say, ‘OK, we are breaking our eggs for all of Europe, but where’s the omelette you are promising us?’

Srećko Horvat

2 DANKE DEUTSCHLAND!

Danke Deutschland, meine Seele brennt!

Danke Deutschland, für das liebe Geschenk.

Danke Deutschland, vielen Dank,

wir sind jetzt nicht allein,

und die Hoffnung kommt in das zerstörte Heim.6

Croatian song, 1992

At the end of 2012, the German President Joachim Gauck visited Croatia. For some reason, I had the honour to be one of three Croatian intellectuals chosen to meet him and have a closed-room conversation about Croatia’s entry to the European Union, but mainly focused on the intellectual and cultural sphere.

When you are invited to meet a president, if you are not a complete idiot, the immediate reaction should be the famous Lacanian lesson that ‘a madman who believes he is king is no madder than a king who believes he is king.’ In other words, a king who believes he possesses an inherent ‘king gene’ is implicitly mad. And the same goes for presidents. A ‘president’ is a symbolical function, even if – or, especially if – he is from Germany (where Angela Merkel runs the game).

In the end, I was pleasantly surprised. It was really interesting to chat with Mr Gauck. He wasn’t just kindly present waiting for the official programme to end, but posed many different questions and showed interest in the Balkans. Although it was planned that culture had to be the main topic of our conversation, politics was in the air. Knowing him not only as an ‘unverbesserlicher Antikommunist’ (‘incorrigible anti-communist’, as the Stasi described Gauck in their file on him), but also as a former Lutheran pastor and someone who seriously studied theology, at one point I asked him a question about the relation between theology and debt, with a political subtext, of course. The question was based on a manuscript from the thirteenth century cited by Jacques Le Goff:

Usurers sin against nature by wanting to make money give birth to money, as a horse gives birth to a horse, or a mule to a mule. Usurers are in addition thieves, for they sell time that does not belong to them, and selling someone else’s property, despite its owner, is theft. In addition, since they sell nothing other than the expectation of money, that is to say, time, they sell days and nights.7

Le Goff offers a detailed analysis of how between the twelfth and fifteenth century a caste of tradesmen developed from a small and despised group into a powerful force not only influencing social relations or even architecture, but first and foremost – social time. What is, according to Le Goff, the hypothesis of the trading activity? Exact timing: the accumulation of supplies in anticipation of famine – buying and selling at optimum moments. In other words, what Le Goff wants to show is that – before the emergence of usurers – in the Middle Ages, time still belonged to God (or to the Church), but today it is primarily the object of capitalist expropriation/appropriation.8

Gauck’s answer about the function of debt was this: ‘It is a matter of responsibility.’ Unfortunately, at this precise moment, as much as I was tempted to do so, I was polite enough not to graze the symbolic function of the President anymore. The question I wanted to pose was, of course, the following one: ‘Is it the responsibility of the German bankers, or of the Greek citizens who depend on the credit?’

And it is not only a question about capitalist domination or financial speculation; it is a theological question par excellence. If our future is sold, then there is no future at all.

And here we come to an interesting episode from recent Croatian history. When at the end of 2012 General Ante Gotovina, considered by many in Croatia as a war hero but ten years ago the biggest obstacle to the European future of Croatia, was freed from the International Court of Justice in The Hague after seven years of imprisonment, the first thing he did when he arrived back was give a speech at the central square in the capital of Croatia, where he offered a calm and terse message to the gathered crowd of 100,000 people: ‘The war belongs to the past; let’s turn to the future!’ Among primarily emotional and some nationalist reverberations, this was the most sober message. But only at first sight.

Only a few days later, asked by a Serbian journalist about his stance towards the return of exiled Serbs to territories liberated by the operation ‘Storm’ (‘Oluja’), the General answered: ‘This is still their home, and I don’t have to invite them back, since you can’t invite someone to his own home.’ He concluded with: ‘But let’s turn to the future!’ The motive of the future as the main motto of the freed general was best summarised by his lawyer during a Croatian TV show. Asked what the General, now the single most popular person in Croatia, would do with his popularity, the lawyer answered succinctly: ‘He will use his popularity to promote the future.’ He added that the acquittal didn’t only justify the past, but also saved the future. Of course, what he forgot to add was that his future was business. Recently he invested in the gasification in his hometown Zadar, worth almost 800,000 euro. So finally, after the war and all this international justice business, we can take what we were fighting for in war – democracy and a free market!

The unavoidable irony of this hyperinflation of the future lies in the fact that never since the break-up of Yugoslavia and the end of the war was there so much public debate and discussion about the past – not about the future. Not only people on the streets, but distinguished political analysts declared that only now ‘the war is over’ and that Croatia was finally ‘free’, which could only mean that until now all of us lived in the past. All of a sudden we were ejected into the future. Politicians, public intellectuals, newspapers, TV shows – all were full of confronting the past, resembling the period in Germany during the 1960s: on the one hand, what did the operation ‘Storm’ really mean (now the Hague Tribunal verdict had made it clear it was legitimised as a liberation operation), and on the other hand, what crimes were still inflicted on the Serbian minority (since the generals were freed, who was now responsible for the crimes that did happen?). Instead of falling into this trap of what Hegel would call ‘die schlechte Unendlichkeit’ (once again all the endless debates were about who killed more people and whose actions and victims were more justified), the General focused himself on the future.

But what does the future really look like? As happens in rare moments, history was condensed within just a few days: at the end of 2012 the Croatian public was surprised by two other judgments that are not only giving a new meaning to the past, but also determining the future. The first verdict was against the former minister of economy, Radomir Čačić, who caused a traffic accident with two fatalities in Hungary in 2010. Although the minister was fully aware that there was a high chance he would end up in jail, he was behaving as if this didn’t concern him as the most important Croatian politician at that time. In a way, the fate of the country was held hostage by his past – because it was clear that he would be convicted, there was no future in his decisions or in his (austerity and privatisation) strategy. The second verdict was a ten-year prison sentence for the former prime minister for ‘war profiteering’. Among other things, Ivo Sanader was found guilty because between 1994 and 1995, during the war, he conferred high-interest rates on loans for Croatia, taking a commission of 5 per cent, which was around 7 million shillings. In other words, what he did during the 1990s directly affected the future of Croatia – namely today’s external debt.

As we can see, the future didn’t die during those seven years when General Gotovina was in prison. The death of the future is inscribed in the very nation-building process. Yes, Croats fought in the war, and many fought really defending their homes and families, truly believing in a better Croatia. But at the same time, the ones who convinced them to fight for Croatia worked hard to steal the future. Sanader setting high-interest rates is the best example. And the other is the once state-owned oil company INA, which is now Hungarian. And there are a number of other cases, which date back to telecommunications, another once-profitable industry that is now German, while all the doors are now open to privatisation of the railway, energy sector, healthcare system etc.

And here again we return to Gotovina and his ‘promotion of the future’. If you think that his vision of the future is an empty gesture without any content, think again. What did the General do right before the Croatians voted in the referendum on joining the EU? Although during his time in prison he hesitated to give any political messages, just a day before the EU referendum he urged all Croatian citizens to go to the referendum and vote for the European Union – and, to be sure the future would be certain, he himself voted in The Hague’s prison cell. It is precisely this perspective which can give us a clear explanation of this hyperinflation of the future, which now gets a clear outline. Just a few days after his ‘futuristic speech’ in Zagreb, he visited the coastal city of Zadar where he admitted that his vision of future was the European Union. Then, eventually, he released a dove of peace into the air.

But doesn’t the future seem a bit different? A long time ago, on one of Zagreb’s façades stood a famous graffiti: ‘We don’t have Cash, how about MasterCard?’ (Namely, the translation of ‘Gotovina’ is neither more nor less than ‘Cash’.) Today we have both, General Gotovina and MasterCard, but we don’t have any cash – we live in an economy of debt. Here the insights of the Italian philosopher Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, known for his thesis about semio-capitalism as the new form of capitalism (financialisation as a process of sign-making), could be useful. In his book The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, he claims that banking is actually about storing time. In a sense, in banks we are storing our past, but also our future. Bifo goes a step further and claims that German banks are full of our time: ‘The German banks have stored Greek time, Portuguese time, Italian time, and Irish time, and now the German banks are asking for their money back. They have stored the futures of the Greeks, the Portuguese, the Italians, and so on. Debt is actually future time – a promise about the future.’9

And if we now interpret the conversation with President Gauck, aren’t precisely German or Austrian banks, among others, storing Croatian time as well? Most of the citizens – not only in Croatia, but in the whole region of the Balkans – are now highly indebted, owing money to foreign-owned banks that have spread around the Balkans and control its whole financial sector. According to some estimation, 75.3 per cent of banks in Serbia, 90 per cent in Croatia and up to 95 per cent in Bosnia and Herzegovina actually belong to German, Italian and French banks.10 The integration of the Balkans into the EU already started twenty years ago!

So, what we should do today is to repeat the famous slogan ‘Danke Deutschland’, but of course, in a cynical manner. When Germany recognised Croatia as an independent state in December 1991, a Croatian singer performed a song under the title ‘Danke Deutschland’ on national television. Although the kitschy song actually wasn’t very popular in Croatia, it clearly shows the prevailing atmosphere: this was the time when many villages and towns in Croatia had a Genscher Street or a Genscher Square, named after the German foreign minister, and even today there are some cafés having his name. As was expected, the song ‘Danke Deutschland’ was immediately used – and played rather more often – in Serbia as a mean of counterpropaganda, which claimed this was further proof of the eternal relationship between Germany and Croatia, namely between the ‘Third Reich’ and the Ustaša regime in Croatia. TV Belgrade went even so far as to play the clip for ‘Danke Deutschland’ over filmed scenes of crowds greeting Germans in the middle of Zagreb at the beginning of the Second World War. Why is it so impossible to imagine such an enthusiasm regarding the enlargement of today’s Europe?

In an early text published during the war, in 1992, Slavoj Žižek developed the famous thesis that the Balkan ‘ethnic dance macabre’ was actually a symptom of Europe, reminding us of a story about an anthropological expedition trying to contact in New Zealand a tribe which allegedly danced a terrible war dance in grotesque death masks. When the members of the expedition reached the tribe, they asked the village to perform it for them, and next morning the performed dance did in fact match the description. The expedition was very satisfied; they returned to civilisation and published a much-praised report on the savage rites of the primitives. But here comes the surprise: shortly afterwards, another expedition arrived at this tribe and they found out that this terrible dance actually didn’t exist in itself at all. It was created by the aborigines who somehow guessed what the strangers wanted and quickly invented it for them, to satisfy their demand. In other words, the explorers received back from the aborigines their own message. And, as you can guess, Žižek’s point is that people like Hans-Dietrich Genscher were the 1990s version of the New Zealand expedition: ‘They act and react in the same way, overlooking how the spectacle of old hatreds erupting in their primordial cruelty is a dance staged for their eyes, a dance for which the West is thoroughly responsible. The fantasy which organised the perception of ex-Yugoslavia is that of the Balkans as the Other of the West: the place of savage ethnic conflicts long ago overcome by civilised Europe, the place where nothing is forgotten and nothing learned, where old traumas are being replayed again and again, where symbolic links are simultaneously devalued (dozens of cease-fires broken) and overvalued (the primitive warrior’s notions of honour and pride).’11 But far from being the Other of Europe, ex-Yugoslavia was rather Europe itself in its Otherness, the screen onto which Europe projected its own repressed reverse.

And doesn’t the same hold for the peripheral countries of Europe as well? Isn’t Greece, soon joined by Croatia, today’s mirror of Europe and all what is repressed in the centre? On the one hand, considering the Balkans still as ‘the Other of the West’, just before the entrance of Croatia to the EU, the European Commission engaged a London-based public relations agency – which usually worked for Coca-Cola, JP Morgan Chase and British Airways – at a cost of 20 million euro to ‘break the myths and misconceptions about EU enlargement’ and to ensure Croatia’s accession was smooth.12 On the other hand, like the aborigines of New Zealand, trying to fit into the Western fantasy, Croatia’s government had to spend 600,000 euro, just before the referendum on the EU, to convince the Croats they would soon become part of civilised Europe.

Already these two details show that the enlargement of the EU is definitely not what it has been before. There is no optimism in the air anymore. And the true question still remains: what does Europe want? And whose responsibility is it for the current state of Europe? This is something this book will try to show, not only questioning the responsibility of the European elites but also rethinking the responsibility of the Left.

Slavoj Žižek

3 WHEN THE BLIND ARE LEADING THE BLIND, DEMOCRACY IS THE VICTIM

In one of the last interviews before his fall, Nicolae Ceausescu was asked by a western journalist how he justified the fact that Romanian citizens could not travel freely abroad although freedom of movement was guaranteed by the constitution. His answer was in the best tradition of Stalinist sophistry: true, the constitution guarantees freedom of movement, but it also guarantees the right to a safe, prosperous home. So we have here a potential conflict of rights: if Romanian citizens were to be allowed to leave the country, the prosperity of their homeland would be threatened. In this conflict, one has to make a choice, and the right to a prosperous, safe homeland enjoys clear priority.

It seems that this same spirit is alive and well in today’s Slovenia, where, on 19 December 2012, the constitutional court found that a referendum on legislation to set up a ‘bad bank’ and a sovereign holding would be unconstitutional – in effect banning a popular vote on the matter. The referendum was proposed by trade unions challenging the government’s neoliberal economic politics, and the proposal got enough signatures to make it obligatory.

The idea of the ‘bad bank’ was of a place to transfer all bad credit from main banks, which would then be salvaged by state money (i.e. at taxpayers’ expense), so preventing any serious inquiry into who was responsible for this bad credit in the first place. This measure, debated for months, was far from being generally accepted, even by financial specialists. So why prohibit the referendum? In 2011, when George Papandreou’s government in Greece proposed a referendum on austerity measures, there was panic in Brussels, but even there no one dared to directly prohibit it.

According to the Slovenian constitutional court, the referendum ‘would have caused unconstitutional consequences’. How? The court conceded a constitutional right to a referendum, but claimed that its execution would endanger other constitutional values that should be given priority in an economic crisis: the efficient functioning of the state apparatus, especially in creating conditions for economic growth; the realisation of human rights, especially the rights to social security and to free economic initiative.

In short, in assessing the consequences of the referendum, the court simply accepted as fact that failing to obey the dictates of international financial institutions (or to meet their expectations) can lead to political and economic crisis, and is thus unconstitutional. To put it bluntly: since meeting these dictates and expectations is the condition of maintaining the constitutional order, they have priority over the constitution (and eo ipso state sovereignty).

No wonder, then, that the Court’s decision shocked many legal specialists. Dr France Bučar, an old dissident and one of the fathers of Slovene independence, pointed out that, following the logic the CC used in this case, it can prohibit any referendum, since every such act has social consequences: ‘With this decision, the constitutional judges issued to themselves a blank check allowing them to prohibit anything anyone can concoct. Since when does the CC have the right to assess the state of economy or bank institutions? It can assess only if a certain legal regulation is in accord with the constitution or not. That’s it!’ There effectively can be a conflict between different rights guaranteed by constitution: say, if a group of people proposes an openly racist referendum, asking the people to endorse a law endorsing police torture, it should undoubtedly be prohibited. However, the reason for prohibition is in this case a direct conflict of the principle promoted by the referendum with other articles of the constitution; while in the Slovene case, the reason for prohibition does not concern principles, but (possible) pragmatic consequences of an economic measure.

Slovenia may be a small country, but this decision is a symptom of a global tendency towards the limitation of democracy. The idea is that, in a complex economic situation like todays, the majority of the people are not qualified to decide – they are unaware of the catastrophic consequences that would ensue if their demands were to be met. This line of argument is not new. In a TV interview a couple of years ago, the sociologist Ralf Dahrendorf linked the growing distrust for democracy to the fact that, after every revolutionary change, the road to new prosperity leads through a ‘valley of tears’. After the breakdown of socialism, one cannot directly pass to the abundance of a successful market economy: limited, but real, socialist welfare and security have to be dismantled, and these first steps are necessarily painful. The same goes for western Europe, where the passage from the post-second world war welfare state to new global economy involves painful renunciations, less security, less guaranteed social care. For Dahrendorf, the problem is encapsulated by the simple fact that this painful passage through the ‘valley of tears’ lasts longer than the average period between elections, so that the temptation is to postpone the difficult changes for the short-term electoral gains.

For him, the paradigm here is the disappointment of the large strata of post-communist nations with the economic results of the new democratic order: in the glorious days of 1989, they equated democracy with the abundance of western consumerist societies; and 20 years later, with the abundance still missing, they now blame democracy itself.

Unfortunately, Dahrendorf focuses much less on the opposite temptation: if the majority resist the necessary structural changes in the economy, would one of the logical conclusions not be that, for a decade or so, an enlightened elite should take power, even by non-democratic means, to enforce the necessary measures and thus lay the foundations for truly stable democracy?

Along these lines, the journalist Fareed Zakaria pointed out how democracy can only ‘catch on’ in economically developed countries. If developing countries are ‘prematurely democratised’, the result is a populism that ends in economic catastrophe and political despotism – no wonder that today’s economically most successful third world countries (Taiwan, South Korea, Chile) embraced full democracy only after a period of authoritarian rule. And, furthermore, does this line of thinking not provide the best argument for the authoritarian regime in China?

What is new today is that, with the financial crisis that began in 2008, this same distrust of democracy – once constrained to the third world or post-communist developing countries – is gaining ground in the developed west itself: what was a decade or two ago patronising advice to others now concerns ourselves.

The least one can say is that this crisis offers proof that it is not the people but experts themselves who do not know what they are doing. In Western Europe we are effectively witnessing a growing inability of the ruling elite – they know less and less how to rule. Look at how Europe is dealing with the Greek crisis: putting pressure on Greece to repay debts, but at the same time ruining its economy through imposed austerity measures and thereby making sure that the Greek debt will never be repaid.

At the end of October last year, the IMF itself released research showing that the economic damage from aggressive austerity measures may be as much as three times larger than previously assumed, thereby nullifying its own advice on austerity in the eurozone crisis. Now the IMF admits that forcing Greece and other debt-burdened countries to reduce their deficits too quickly would be counterproductive, but only after hundreds of thousands of jobs have been lost because of such ‘miscalculations’.

And therein resides the true message of the ‘irrational’ popular protests all around Europe: the protesters know very well what they don’t know; they don’t pretend to have fast and easy answers; but what their instinct is telling them is nonetheless true – that those in power also don’t know it. In Europe today, the blind are leading the blind.

Srećko Horvat

4 WHY THE EU NEEDS CROATIA MORE THAN CROATIA NEEDS THE EU

When in late 2005 the accession negotiations between Croatia and the EU officially started, a leading Croatian liberal daily triumphantly published the following headline all over its front page: ‘Bye, bye Balkans!’ At that time, this was the prevailing and typical stance towards the European Union: some sort of ‘self-fulfilling mythology’ of the Balkans as a region needing to be ‘civilised’ by integration into the West. Only eight years later, as Croatia finally becomes part of the European Union, neither the EU nor the Balkans has the same image anymore. Today’s situation is somehow reminiscent of the famous joke about a patient whose doctor makes him choose whether to hear the bad or the good news first. Of course, the patient chooses first to hear the bad news. ‘The bad news is you have cancer,’ says the doctor, ‘but don’t worry, the good news is you have Alzheimer’s, so when you get home you will already have forgotten about the first predicament.’ Doesn’t that sound just like the situation with Croatia’s EU accession, where the bad news is that Croatia is experiencing a political and economic crisis, with corruption affairs erupting almost on a daily basis and unemployment rates rising as well, and the good news is: ‘Don’t worry, you will enter the EU’?

‘A clear majority in favour of EU accession’ is how the teletext of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation reported on the referendum in Croatia regarding the country’s EU membership. And indeed, two-thirds of the votes cast said ‘Yes’. But taking into account the historically low turnout in the referendum of 43 per cent, this means that actually not more than 29 per cent of the population entitled to vote spoke out in favour of EU accession. On the eve of Croatia’s EU referendum, the former war general Ante Gotovina, recently released from his ICTY prison cell in The Hague, and who had once been the biggest obstacle to the Croatian negotiations with the EU, sent an epistle to the Croatian people urging them to vote in favour of the EU. At the same time, the two biggest Croatian parties, the Social Democrats (SDP), now in power, and the Conservatives (HDZ), the former ruling party, together with the Croatian Catholic Church, did everything to convince the voters that ‘there is no alternative.’

Only a few days before the referendum, the foreign minister even went so far as to point out that pensions would not be paid unless the vote was ‘Yes’. And, thanks to a ‘Yes’ campaign that cost around 600,000 euro, the main arguments were a similar type of ‘blackmail alternative’, among which the most frequent was: ‘If we don’t enter the EU, we will stay in the Balkans.’ In such an atmosphere it is no surprise that the referendum on Croatia’s accession to the EU recorded the lowest turnout among all current member states. With an attendance of only 43 per cent of its citizens, Croatia has beaten the previous record holder, Hungary, where the referendum was attended by 45 per cent. One possible explanation was nicely formulated by Croatia’s prime minister after the first official results: ‘Afraid that the referendum might fail, we changed the Constitution’, involuntarily echoing the famous proverb by Bertolt Brecht: ‘When government doesn’t agree with the people, it’s time to change the people.’ Not only were the rules of the referendum indeed changed in 2010 because of the EU accession, but also other (legal, economic etc.) things were settled beforehand.

When, only six days after Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation which triggered the ‘Arab Spring’, 41-year-old TV engineer Adrian Sobaru attempted to commit suicide during the Romanian prime minister’s speech in parliament by throwing himself off the gallery dressed in a T-shirt saying, ‘You have killed our children’s future! You sold us!’ almost no-one took this as an indication of what was going to happen in the European Union. Only a year later, thousands of Romanians protested against austerity measures (mainly provoked by the privatisation of the healthcare system). Unlike at the time of the enlargement of the European Union in 2004 or 2007, there is no optimism in the air anymore – and yet, Croatia is joining the club.

Only last year the EU was facing huge protests and several general strikes from Spain, Portugal and Greece to England, Hungary, Romania and future member state Croatia.13 And there is a new anti-democratic tendency in the EU, which does not only manifest itself in the success of right-wing movements (Golden Dawn, etc.) and governments (Viktor Orbán). An even bigger threat to democracy is the new technocrat elites in power; people who are actually provoking new nationalist tendencies and who all have one thing in common: they all worked for Goldman Sachs; people such as Mario Monti, Mario Draghi or Lucas Papademos. Actually, the last one is the best example for what is wrong with the EU today. If we play with the etymological meaning of ‘papa’ (which means ‘father’ and ‘goodbye’), at the same time you have a ‘father of the people’ (Papa demos) and someone who is saying ‘goodbye to the people’ (Pa-pa demos). When we spoke about this weird congruity, Slavoj Žižek made a brilliant Hegelian synthesis: if you put the two together, you have neither more nor less than the mythology of Saturn who is eating all of its children, except Jupiter! (Namely, ‘papa’ in Croatian and Slovenian language also means ‘eating’.)14

Actually, the Croatian referendum was another symptom of the EU’s democratic deficit. We had a referendum after everything was already settled. We did not have a referendum in 2003, when Croatia applied for EU membership. We did not have a referendum in 2005, when Croatia officially opened negotiations with the EU. We did not even have a referendum in 2010, when our Constitution and the rules of the referendum were changed because of future EU membership. In other words, today we are in a situation where we can only choose what was already chosen throughout these stages. The question, repeated continuously by the Croatian government, ‘What is the alternative?’ already sounds like blackmail and is strangely reminiscent of the there-is-no-alternative-slogan made famous by Margaret Thatcher. And it is not by chance that we have a paradox here in the shape of an allegedly social-democratic government actually putting forward neoliberal reforms faster and more efficiently than the former conservative government. Already now – as a plan to ‘rescue’ the economy – this social democratic government is announcing gradual privatisations of highways and railways, the energy sector and even prisons.

At the same time we witness the bizarre situation where the government is trying to convince the people that Croatia has to join the EU because, firstly, we will no longer be part of the Balkans anymore, and secondly, we will finally be part of the West. Sometimes it is enough to take a look at the path of the previous candidates who are now full members of the club, to see what sort of mythology haunts each new member state. In his provoking book Eurosis – A critique of the new Eurocentrism, Slovenian sociologist Mitja Velikonja made an extensive discourse analysis starting from the observation that the infinitely reproduced mantras of the new Eurocentric meta discourse have caught on and became normalised within all spheres of social life: in politics, in the media, in mass culture, in advertising, in everyday conversations. In his own words: ‘Never during the one-party era of the uniformity of mind under Yugoslav totalitarianism did I see as many red communist stars as I saw yellow European stars in the spring of 2004, that is to say, under democracy.’15 In short, what we have is a kind of ‘virosis’, therefore the neologism ‘Eurosis’.

The pattern is always the same: according to the then Slovenian foreign minister, by joining the EU, Slovenia has come ‘one step closer to the European centre, European trends, European life, European prosperity, European dynamics and the like’. On the other hand, all things that are ‘backwards’, ‘bad’ or ‘out’ stand for – you can guess – the Balkans. Or, as one journalist said in the Spanish daily El Pais, ‘By joining the EU, Slovenia escaped the Balkan curse.’ But if we take a closer look, Europe is ‘Balkanised’ already, and, on the other hand, the Balkans is ‘Europeanised’ as well. This can be best explained if we look at the main myths circulating in the Balkan region since Slovenia entered the EU and moving from one candidate to the other, finding its temporary resort in Croatia and waiting to transmigrate to other countries such as Montenegro or Serbia. The first myth is the one about corruption, the second on prosperity and the third brings us to the recent Nobel Peace Prize.

Here is the first myth: ‘When we enter the EU, there will be less corruption.’ By now, almost everyone knows about the Hollywood-like story of Croatian ex-Prime Minister Ivo Sanader, escaping from Croatia and being caught on the highway near Salzburg. He was accused of several corruption affairs, including an Austrian bank (Hypo-Alpe Adria) and Hungarian oil company (MOL). In other words, without European partners, he couldn’t be involved in these corruption affairs. The last discovery is a ‘deal’ made between Sanader and Sarkozy, because of which Croatia’s national carrier, Croatia Airlines, faces bankruptcy unless it can change a contract that was signed in 2008 by the former prime minister. Sanader struck a deal worth 135 million Euros with the former French president, to buy four planes back in 2008 with Airbus France. Croatia Airlines didn’t really need the planes, but it was Sanader’s ticket to secure a meeting with Sarkozy, just before France took over the presidency of the Council of the EU. At the same time, Jacques Chirac was found guilty of corruption and the German President Christian Wulff had to resign because of alleged corruption. So much about the thesis there will be less corruption in the EU than in the Balkans. What we are facing here is a clear case of applying double standards perfectly illustrated by a recent edition of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung where Commission President Barroso gave a big interview claiming we need ‘more Europe’, accompanied by a small piece of news that Romania won’t get the green light to enter the Schengen Zone. Why? Because of corruption. So speaking about ‘reforms’ and ‘monitoring’, why isn’t the same applied to the EU itself? And to take it to the extreme: why shouldn’t new member states ‘monitor’ the EU?

And here we come to the second myth: ‘When we enter the EU, there will be more prosperity.’ It is not difficult to dispute this myth. It’s enough to look at the ‘prosperity’ of PIIGS or, as they have recently been called, the GIPSI, an expression which, by the way, perfectly illustrates the actual significance of the periphery for the centre. Croatia will not join the centre – it will be part of the GIPSI states. Recent statistics show that Croatia – with more than 50 per cent – is the third country in Europe when it comes to youth unemployment, after Greece and Spain. As the Polish philosopher Jaroslaw Makowski noticed, ‘Until now, sociologists have focused on the so-called “lost generation”, but politicians had been wary of using the phrase, until Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti broke the conspiracy of silence, telling his young compatriots: “You’re a lost generation.” Or, more precisely, “The truth, and unfortunately it’s not a pleasant one, is that the promise of hope – in terms of transformation and improvement of the system – will be only for those young people who will come of age in a few years.”’

Instead of precisely investing in young people, Monti even went so far to say that ‘young people will have to get used to the idea of not having a fixed job for life’, and added: ‘which is moreover, monotonous! It is much nicer to change and accept new challenges’. So on the one hand, as Makowski explains, you have the ‘enraged youth’, which we saw in action in London’s streets in summer 2011, the ‘new poor’ facing a prospect of protracted unemployment or flexi-jobs below their qualifications and ambitions, and on the other hand, although it is exactly the Erasmus generation that is Europe’s last resort, education is being scrapped as part of ‘austerity measures’.16 Maybe the time has come to paraphrase the famous saying by Max Horkheimer and say, ‘Anyone who does not wish to talk about neoliberalism, should also keep quiet on the subject of the EU.’ And the same goes for ‘reforms’ in Croatia. Those who don’t wish to talk about the reforms of the financial sector should also be quiet on the subject of all other (legal, human rights etc.) reforms. Already more than 90 per cent of banks in Croatia are Austrian, French, German or Italian, and the Croatian ‘euro-compatible’ elites are trying to implement further neoliberal reforms portrayed as a necessary part of the EU accession process. And maybe this is what Mr Barroso meant when he was saying that Croatia’s accession to the EU will only strengthen the EU (with new privatisations and new capital flows).

The third myth linked with the myth of prosperity is the following: ‘When we enter the EU, there will be more stability.’ Or as one liberal Croatian intellectual put it before the referendum: ‘For us the option is clear: either the Balkans or the civilised nations’, and his colleague added: ‘Eurosceptics are just bigoted obscurantists, maniacal patriots, fans of war criminals and tragicomic visionaries.’ This is the old myth, reinforced for example by Emir Kusturica’s movies, which show the Balkans as a dark region only good enough for war crimes. It is the ‘Imaginary Balkans’ so well explained in Maria Todorova’s classic book under the same title. But when the European Union got the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize for having ‘contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe’, it was exactly this myth which was repeated in the official press release by the Norwegian selection committee: ‘The admission of Croatia as a member next year, the opening of membership negotiations with Montenegro, and the granting of candidate status to Serbia all strengthen the process of reconciliation in the Balkans.’ Here you have it again, a celebration of the European Union’s mission ‘civilisatrice’, although it was exactly the EU that failed to stop massacres like that in Srebrenica. However, it is not really necessary to discredit the Nobel Peace Prize: by the time Henry Kissinger got it, it was obvious that Orwell’s famous credo ‘War is Peace’ had become a new motto for its awarding, a suspicion confirmed by the choice of Obama, who afterwards did not withdraw his troops from either Iraq or Afghanistan. Nevertheless, it is necessary to mention that one of the prerequisites for joining the EU is to be a part of NATO, not really known for ‘strengthening the process of reconciliation’ if we have in mind the war in Libya or other places. Or take the recent war in Mali, where the EU is again sending troops to fight ‘Islamic fundamentalism’ under the pretext that it is endangering European democracy. It is also worth mentioning that the current presidency holder of the Council of the EU is Cyprus, a still divided country, and that the Nobel Peace Prize is given in a country whose citizens twice refused EU membership. All in all, the myth of ‘stability’ goes hand in hand with the myth of ‘prosperity’, as there is no real peace in Europe, but exactly the opposite – a permanent economic warfare going on in the ‘bay of PIIGS’. Is there any better proof than the submarine deals that helped sink Greece, the billions spent on buying German U-boats while the EU is pushing for deeper cuts in areas like health or education?

So maybe the time has come to change the doctor joke and switch the roles. The bad news is that the EU is in a big political and economic crisis, with corruption affairs erupting almost on a daily basis and unemployment rates rising. The good news is that Croatia is entering the EU: it is precisely Croatia’s accession, just like the Nobel Peace Prize, that should give new credibility and legitimacy to the European Union in its current state. In that sense, we could say that at this moment the EU needs Croatia more than Croatia needs Europe in the state it is currently in.

Slavoj Žižek

5 WHAT DOES EUROPE WANT?

On 1 May 2004, eight new countries were welcomed into the European Union – but which ‘Europe’ will they find there? In the months before Slovenia’s entry to the European Union, whenever a foreign journalist asked me what new dimension Slovenia would contribute to Europe, my answer was instant and unambiguous: nothing. Slovene culture is obsessed with the notion that, although a small nation, we are a cultural superpower: We possess some ‘agalma’, a hidden intimate treasure of cultural masterpieces that wait to be acknowledged by the wider world. Maybe this treasure is too fragile to survive intact the exposure to the fresh air of international competition, like the old Roman frescoes in that wonderful scene from Fellini’s Roma, which start to dissolve the moment that daylight reaches them.

Such narcissism is not a Slovene speciality. There are versions of it all around Eastern Europe: we value democracy more because we had to fight for it recently, not being allowed to take it for granted; we still know what true culture is, not being corrupted by the cheap Americanised mass culture. Rejecting such a fixation on the hidden national treasure in no way implies ethnic self-hatred. The point is a simple and cruel one: all Slovene artists who made a relevant contribution had to ‘betray’ their ethnic roots at some point, either by isolating themselves from the cultural mainstream in Slovenia or by simply leaving the country for some time, living in Vienna or Paris. It is the same as with Ireland: not only did James Joyce leave home in order to write Ulysses, his masterpiece about Dublin; Yeats himself, the poet of Irish national revival, spent years in London. The greatest threats to national tradition are its local guardians who warn about the danger of foreign influences. Furthermore, the Slovene attitude of cultural superiority finds its counterpart in the patronising Western cliché which characterises the East European post-communist countries as retarded poor cousins who will be admitted back into the family if they can behave properly. Recall the reaction of the press to the last elections in Serbia where the nationalists gained votes – it was read as a sign that Serbia is not yet ready for Europe.