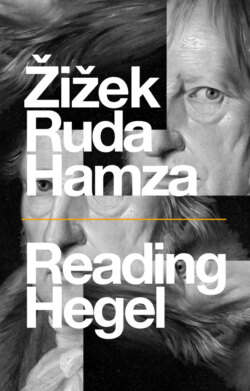

Reading Hegel

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Slavoj Žižek. Reading Hegel

CONTENTS

Guide

Pages

Reading Hegel

Notes on the text

Introduction

Notes

1 Hegel: The Spirit of Distrust. Hegel in a Topsy-Turvy World

Reconciliation in Hegel

“Forgiving Recollection”: Yes, but …

From Concrete Universality to Subject

How does “Stubborn Immediacy” Arise?

The Alethic versus the Deontic

What is Absolute in Absolute Knowing

“Ungeschehenmachen”

The Parallax of Truth

Method and Content

Notes

2 Hegel on the Rocks: Remarks on the Concept of Nature

New Geriatrics, or: Newly Born Old

Nature’s Compulsion to Return

Philosophy Begins. The (Eight) Dialectics of Nature

Falling For …

… and Cresting Nature

From Nature as Fragment to the System-Fragment

Nature in Jena (as Substance but also …)

The Other-Being of the Idea

From Natural Substance to Conceptual Subject …

… to Releasing Nature

Unavoidable Naturalization

Notes

3 The Future of the Absolute

Hegel Today

Marx’s Critique of Religion

The foundation of irreligious criticism

The mist-enveloped regions of the religious world

Hegel and Christianity

Theory of the State

Dialectic and Politics in Hegel

Notes

Index. A

B

C

D

E

F

H

I

K

L

M

N

O

P

R

S

T

U

Z

POLITY END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT

Отрывок из книги

Slavoj Žižek, Frank Ruda, and Agon Hamza

There is certainly a farcical dimension to the immediate aftermath of Hegel’s thought. This is already the case, because (some of) his pupils prepared and published an edition of his works that became highly influential to most of his subsequent readers, and which consequently led, to some degree, to profound confusion about the true kernel and thrust of Hegel’s philosophical system, and – by adding comments and annotations that were taken to be his very own wording – generated a peculiar struggle about Hegel’s ultimate achievements (and failures). Surprisingly material from this edition was nonetheless able to become, for long, the main reference for reading Hegel – a sort of manifestation of the Deckerinnerung, the screen memory that overshadows what one perceives to be Hegel’s ultimate philosophical system.2 However, the immediate Hegelian aftermath also already inaugurated, among other things, the infamous split between the young and the old Hegelians, which seemed to practically and farcically enact Hegel’s own claim that any immediate unity (and thus also that of the Hegelianism and of Hegel himself) will need to undergo processes of alienation and division to, at least possibly, reinstate the original unity in a reflected form. Does Hegel’s ultimate tragedy, in both senses of the term, lie in the fact that immediately after his death his philosophy was not only dissected and rebutted, but there was also a farcical element in the defense of a Hegel that was articulated in words he never wrote against critics who got it all wrong? So, did the farce not simply prove the tragedy to be a real tragedy? One could also, in both enlarging the historical focus and in locating the ultimate embodiment of the repetition of Hegel’s tragedy as farce, identify the tragedy of Hegel’s oeuvre with the fact that the arguably most influential and important pupil of the thinker who was by many perceived to have been a Prussian state philosopher (Hegel), has been one of the most influential and famous contenders of revolution and of overthrowing the state, namely Marx. May then not Marx’s ultimate Hegelian heritage – again confirming the tragedy–farce sequence – be identified in the fact that he himself not only witnessed as many rebuttals as Hegel, but was actually often claimed to have been the one who put (revolutionary) dialectic into practice, and thereby refuted it even more harshly, due to the brutal and bloody outcomes of his thought when concretely realized?

.....

Reading Hegel has been completed about three years after Reading Marx – the first book on which the three of us worked together. This move (from Marx to Hegel) is not accidental. It is our firm conviction that our contemporary predicament calls for a return from Marx to Hegel (that we also noted in our previous book). This return does not consist only of the “materialist reversal” of Marx (a thesis elaborated and developed in length by Žižek), but its implications and consequences are much deeper (for example the development and affirmation of an idealism of another kind, an idealism without idealism). So, why return (from Marx) to Hegel?

Hegel was born about a quarter of a millennium ago. Then, as the famous Heideggerian adage goes, he thought and then he finally died. One hundred and twenty-five years after his death, Theodor W. Adorno remarked that historical anniversaries of births or deaths create a peculiar temptation for those who had “the dubious good fortune”5 to have been born and thus to live later. It is tempting to believe that they thereby are in the role of the sovereign judges of the past, capable of evaluating everything that and everyone who came before. But standing on a higher pile of dead predecessors and thinkers does not (automatically) generate the capacity to decide the fate of the past and certainly it is an insufficient ground to judge a past thinker. A historical anniversary seduces us into seeing ourselves as subjects supposed to know – what today still has contemporary significance and what does not. They are therefore occasions on which we can learn something about the spontaneous ideology that is inscribed into our immediate relationship to historical time, and especially to the past. Adorno makes a plea for resisting the gesture of arrogantly discriminating between What is Living and What is Dead – for example – of the Philosophy of Hegel.6 Adorno viciously remarked that “the converse question is not even raised,” namely “what the present means in the face of Hegel.”7 The distinction between what is alive and dead, especially in the realm of thinking, should never be blindly trusted to be administered only by those alive right now. Being alive does not make one automatically into a good judge of what is living and not even of what it is to be alive.

.....