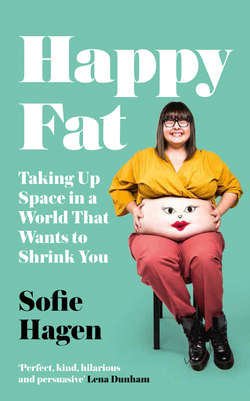

Читать книгу Happy Fat: Taking Up Space in a World That Wants to Shrink You - Sofie Hagen - Страница 6

Introduction

ОглавлениеHi, I am fat. I am also thirty years old, Danish and a Scorpio. I am a person who only recently felt adult enough to buy non-plastic plants. I have owned more instruments (three) than I have learned to play (zero). My favourite colours are red and purple. I have worked in an antique bookshop, a bakery, a sex shop (where they either believed me when I said I was older than I was, or just didn’t care), a video store (from which I stole sweets), a posh grocery shop, a kindergarten (from which I got fired when the children asked me to pretend to be a Sleeping Grown-up and I actually fell asleep for an hour), and various charity organisations as both a street fundraiser and a telemarketing fundraiser. That was my last normal job before I started doing stand-up comedy. I have won a few big stand-up comedy awards such as the Edinburgh Comedy Award for Best Newcomer. I have a poster on my wall of a flying llama saying ‘¿Que Pasa?’ and I laugh every time I see it. I had my first article published when I was thirteen. It was about the pop singer P!nk and it was in a Danish teen magazine called Vi Unge. I had my first two-page spread published in a free newspaper called MetroExpress when I was fifteen. It was about How to Be the Best Westlife Fan. I love musical theatre and I love going to the cinema alone. I prefer dogs to cats. I also prefer dogs to most humans. I am many, many things other than my weight. I am sure you are too. I don’t wish for my fatness to define me any more than I want Kindergarten Sleeper, Westlife Fan or Dog Lover to define me.

But when people see me, they see the fat. They judge and notice the fat. Despite this, they rarely say the word fat. That is why it’s part of the title of this book. FAT. I say it as often as I can. FAT. In the hopes that the more I say it, the less scary it will seem. We all have fat on our bodies, it’s only the volume of it that differs from person to person. Fat is essentially energy. Fat is protecting our organs. And fat is just a descriptive word. The negative connotations came later; hissed at us by a parent, shouted from a moving vehicle, or written in yellow all-caps letters on the front cover of a magazine as a warning.

A lot of effort is put into denying fat. Phrases like ‘You have fat, you are not fat’ and ‘I am not fat, I’m just easy to see.’ The intention is sweet, but it does nothing but reaffirm that fat is bad. This is all called fatphobia. The fear of fatness. This is a message we see constantly – from adverts on television, through fat characters in movies who either don’t exist or are portrayed negatively, through your mother asking if you’ve gained weight with a sneer, your friends talking about their new diets, the high-street clothes shops not catering to a size bigger than 12, through the lack of fat people on the covers of magazines and the constant news stories telling us that the obesity epidemic is coming to get us all. Everything has the basic underlying message that it is positive to be thin and negative to be fat.

Of course, if a woman is thin, she will be wrong in other ways. She will be too thin, not the right shape of thin, not the right height, not have a large enough gap between her thighs – and she needs to smile more but not too much, because that would be slutty. She needs to laugh but not at her own jokes, preferably men’s jokes. She needs to wear a dress that’s not too long because then she is a prude but also not short because then she is a whore. Her breasts have to be big – but not vulgar-big and not big in length. And she most importantly has to never complain about these extreme and impossible beauty standards and society’s wish to make her into an accessory.

There is a growing amount of pressure on men to look a certain way as well – but usually, they are given a slightly bigger pass than women are. Yet, even if they do get a big pass, fat men are still not allowed to be fat.fn1 Fat is frowned upon, regardless of who embodies it and regardless of how much they embody. Trashy magazines will find even the slightest bulge on the stomach of a celebrity swimming in the ocean and plaster her all over the front cover of their magazine as an example of someone breaking the rules: by not staying thin.

Fat is perceived to be an exclusively negative thing. And it isn’t. And it doesn’t have to be.

That’s the essence of this book. Fat is not an inherently negative word. Fat is, if anything, neutral. But it can be beautiful, it can be loved, it can be absolutely magnificent. You can be fat and sexy, fat and healthy, fat and happy.

I love my body. I love my stomach with all of its red stretch marks hanging like an impractical bum bag over my thick, fleshy thighs which spread out and drape slightly over the sides when I sit in a chair. My double and, sometimes, triple chin. The jiggly flesh on my arms where there are, in theory, somewhere deep down, triceps. There is so much fat there that I can grab a fistful of it. My body is many, many fistfuls of fat. When I wear a bra, bulges of fat pop out right above the strap under my armpits, creating side boobs. My cheeks are thick, so thick that when I smile, they almost cover my eyes completely. I smile a lot. I would tell you how much I weigh, but I don’t know. I stopped weighing myself years ago.

I have never been thin and I will never be thin.

I am a fat person and I love my body. I feel lucky to be able to say that. It has never come easy. It has taken a lot of work and a lot of time to get here. I often meet people who are incredibly puzzled that I can love this body. Taking the world into account – how we are taught to see bodies and judge bodies – I understand the puzzlement. But I am quite sure I can explain it. I want to tell you what I have learned and how I got here.

Essentially, this book is a beginner’s guide. A look into the world of being a fat person.

More specifically, what it is like to be me – a white, pansexual,fn2 West European person. On top of which, I come across as straight – meaning that people can’t see all the internal feelings of oh actually I want to kiss girls and oh actually I’d like to kiss everyone. I am, at this moment in time, nondisabled. In the moment of writing this book, I call myself fat. There are loads of different terms you can use to describe your body, but the most commonly used ones within fat activism are big-thin, small-fat, fat, super-fat and infinity-fat.fn3 It’s hard to define. All bodies are so vastly different that you can’t really make an official definition. Two people weighing the same could look completely different – and therefore be treated very differently by society. One person who is a size 28 could fit into an airplane seat whereas another person who is a size 24 could not. I am somewhere in between ‘fat’ and ‘super-fat’. I can buy clothes in most online plus-size clothes shops, but I cannot fit into most seats that have armrests. Infinity-fats can definitely not do any of those things. Big-thins never have to worry about either.

This book is very much from a West European perspective and primarily deals with West European culture. It’s important for me to say this and, I guess, for you to read this, because it is worth noting that there are other viewpoints out there. It is always important to be aware of privilege – be it your own privilege or the privilege of the author whose book you’re reading.fn4 But it is not for me to speak on behalf of others – instead, I talk about me and my experiences. Over the course of the last decade, I have read books and articles, studies and opinion pieces, I have watched documentaries and attended conferences, interviewed experts, scholars and highly experienced activists, all about fatphobia and its causes and its consequences. So even though my perspective is my own and as everything (hu)man-made, fundamentally subjective, the only reason I felt comfortable writing this book is that I feel like I have enough empirical knowledge to back up what I will be telling you.

Throughout the book, I have incorporated chats that I have had with people with different life experiences from my own. It’s also a way of showing intersectionality at play. I have talked to Stephanie Yeboah, who is a dark-skinned black and fat woman from London, and who – just by existing – has to deal with fatphobia, racism and colourism. There is Kivan Bay, a fat, trans, queer man from Portland, US, who has to live with fatphobia, transphobia, queer- and homophobia. And Matilda Ibini, a black woman in a wheelchair from London, who has to deal with racism, colourism, body shaming and ableism. You can’t separate just one ‘marginalisation’ on its own – which is why I urge you to not skip these chats. They are all incredible people whom I very much enjoyed talking to. If their life experiences are not similar to your own, it is still important to include them in your journey. I’m so grateful for their input.

I also have a chat with Dina Amlund, a Danish cultural historian who focuses on fatness, who is here to fix one of our most common misconceptions within our ideas of fatness. I am very excited and proud to share her viewpoint with you.

This book is for everyone. Absolutely everyone. But I have lived as a fat woman, I relate to fat women, I relate to queer people; people who sometimes feel like they are on the outskirts of society. I have written this book for everyone, but if you are not fat, if you are a cis man, you may at times feel left out or unattended to. This is not because I am purposely leaving you out. But I have lived for thirty years now consuming art and media made by thin, white, straight cis men who have subconsciously or consciously primarily addressed other thin, white, straight, cis men, and rarely have they tried to include me or my fellow outsiders into their world, as anything but the joke or the accessory. Yet, when asked, they would probably also claim that their art was for everyone as well. So that is what I am saying to you now: this book is for everyone. If you do not relate to being fat, if you do not relate to being a woman or if you do not relate to being an outsider in any way, you should still read it. I just don’t pander to you. We fatties have very little that is made by us, for us. So if you are fat, this is particularly for you. The fat, the weird, the queer, the neuroatypical,fn5 the confused and the excluded.

In this book, I am going to talk about growing up as a fat child, a fat teenager and becoming a fat adult. I am going to talk about dieting and, most importantly, failing at it. I am going to talk about the ridicule and humiliation, the ostracism and the trauma, the rejection and the heartbreak. I am going to talk about belly rolls, stretch marks and the red marks you get between your thighs when they have been rubbing together.

This is not a book about body positivity. I will mostly use the term ‘Fat Liberation’. Body positivity gained momentum fairly recently – it came with TV adverts showing slightly chubby (at best) models using certain lotions or tights. It came with a lot of caveats: you can be slightly bigger than a size 10, but it’s preferable if you have an hourglass figure. The fat is acceptable if it is in the right places and if there is not too much of it. Super-fat people are still not represented and there is a noticeable focus on fatties who exercise or eat salads. Another caveat: you can be fat if you at least are trying to lose weight.

It may seem like there has been a lot of progress recently, but it isn’t fair to say that the progress has been made for fat people. We may have more adverts on TV featuring what they call ‘real women’ (yawn) but at the same time, clothing brands are removing their plus-size collections from their physical stores and the world seems to want us to exist less and less. For example, only as recently as March 2018, Thai Airways banned fat people from using business class.1

Fortunately, due to social media, we can control a lot of what we see. In the back of the book, I have a list of some fat role models and fat activists who are all making a big difference. But when you look at popular media – your average TV commercial or women’s magazine, or when you look at the news, the very best we can hope for is a fat person struggling to lose weight or a thin person in a fat-suit. And maybe a message from some beauty brand saying ‘buy this lotion for real women’ which then features a few cis women who are all a size 10–12. Maybe one of them has short hair so the brand looks super diverse. That’s body positivity.

This is all so far away from what the original Fat Liberation movement stood for. By using the word ‘body’ instead of ‘fat’, we easily lose sight of what the core of the body image issue is: the hatred of fatness and fat people. By allowing the focus to rest on the ‘body positivity’ movement, we are allowing wealthy companies to cash in on a fight that has been fought by fat activists since the 1960s. Fat activism is very rarely about the individual’s struggle with their self-esteem or feelings about their stretch marks. It is about changing the anti-fat bias, particularly the way it affects fat people politically. For example, it is still legal to discriminate against a person based on their weight in the UK,2 49 states in the US (the only state that has made it illegal is Michigan)3 and a majority of countries all over the world. We are not a protected group. Fat people are, on average, paid less and have a harder time getting employed.4 So where there is definitely a reason for also talking about the individual’s self-esteem (I go fully at it in the chapter ‘How to love your body’, for example), it is so utterly important that we remember and understand where this whole thing started. The incredible people who fought for us and before us.

The fat-activism movement started in the US in 1967. Five hundred fat people had a ‘Fat-In’ in Central Park in New York, where they ate ice cream and burned diet books.fn6

The ‘National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance’ was founded in America in 1969, by a guy called Bill Fabrey in response to discrimination against his wife.fn7 Today NAAFA is seen more as a politically motivated group, but during the sixties they were much more of a social club for fat people. The San Francisco chapter of NAAFA were a bunch of wild and awesome lesbians and queer women, many of whom were Jewish, who started becoming vigilant about fat hatred in the scientific community and wanted to fix that. NAAFA considered this to be a bit too dramatic, so the San Francisco chapter splintered off and, in 1972, became the Fat Underground. They coined phrases such as, ‘A diet is a cure that doesn’t work, for a disease that doesn’t exist.’5

In 1983, the Fat Underground and the New Haven Fat Liberation Front released the book Shadow on a Tightrope, a collection of poems, articles and essays by and about fat women and their lives and in the UK, The London Fat Women’s Group was started in 1985. The terms used around this time were Fat Liberation, Fat Pride and Fat Power. The Fat Liberation movement, alongside the Fat Pride and Fat Power movement, was not too bothered with how the individual felt about their body. It was a critique and a fight directed against the structural oppression, the discrimination and the inherent fatphobia (the hatred of fat bodies) in society. The focus was not on how much you should ‘love your curves’; they just wanted to be free. In 1973, two fat activists, Judy Freespirit and Aldebaran, released the Fat Liberation Manifesto, which you can read at the back of this book, and it’s still as relevant today as it was back then.

Around the same time, a lot of Fat Liberation and body-revolution politics were also being discussed by black feminists and black womanists.fn8 Fat black women have had to fight sexism, racism and fatphobia, attacks on the colour of their skin, their perceived gender and the size of their bodies. In a 1972 edition of the American feminist magazine Ms., Johnnie Tillman wrote: ‘I’m a woman. I’m a black woman. I’m a poor woman. I’m a fat woman. I’m a middle-aged woman. And I’m on welfare. In this country, if you’re any one of those things you count less as a human being. If you’re all those things, you don’t count at all. Except as a statistic.’ In 1984, Guyanese-British poet Grace Nichols released the book The Fat Black Woman’s Poems.

It is worth noting that the movement that has now been overtaken by corporations was started by women who were primarily fat, Jewish, black and queer. None of whom would be likely to feature in the adverts for lotions by these ‘body positive’ companies, or would be able to buy clothes in a shop using ‘curvy’ models to ‘promote body positivity’. They took the ‘fat’ and replaced it with ‘body’ to erase the very existence of fat people and make it more palatable and sexy to consumers. They then took the searing and urgent call to arms that is the word ‘liberation’ and changed it to ‘positivity’, almost as if to say: ‘Shh, sit down, don’t make a fuss. Smile. Smile and be still-quite-thin.’

And we all know how women love to be told to smile.

A good thing about the body-positivity movement is that it is most likely what led you to my book. I am very much a spreader of ‘love yourself’ rhetorics. I use hashtags such as #HappyFat and I have a chapter in this book called ‘How to love your body’. I have been featured in many ‘Body-Positive Babes You Must Follow on Instagram!’ articles. And I would love for you to love your body, because it’s a wonderful feeling. But don’t get me wrong – I need you to love your body, so you can join me in the revolution. So one day you’ll join me in a park for ice cream and diet-book burning like those who came before us.

But let’s not focus on the far-away future right now. This is just the introduction, where I wrap you in a blanket, introduce myself and the topic of fat, and prepare you for what you are about to read. We can plan the revolution when you have finished the book.

When I set out to write this book, I wanted, first and foremost, to put into words what being fat has been like for me. In doing small, intimate readings of the initial draft to an audience, I learned that I am very much not alone with these feelings. It made me feel less alone and I sincerely hope you will feel the same way when reading this book. As I mentioned, you will find a whole chapter full of advice on how to love your body. What a grandiose statement. I will debunk all the damaging myths about fatness and health like many others have done before me and like so many others will have to do in years to come. I will reach out to you non-fats reading this book – you get your very own chapter. I wanted you to know how you can be a better friend to fat people. Oh, also, I wanted to refer to myself as the ‘Bang Lord’ at least once. And drag a lot of people who wronged me because I am vengeful, I never forget and I latch onto grudges like I am my brother twenty years after I convinced him to sell his shares in Google because it would never take off. #YahooForever. There are also lovely illustrations sprinkled all over the book by the amazing fat illustrator, Mollie Cronin.

Before you start the book, I want you to do something that I often have had to do throughout writing it. Put your hands on your stomach – or your thighs, your upper arms, your double chin or whatever area on your body that you have struggled with the most – and close your eyes. Give yourself a nice little cuddle. Whisper, ‘We are going to be okay. I love you.’ Because chances are, you will have said a lot of crap to your body in your life and we are about to dig into some of that. I’d love for your body to come with you. If this is all too cutesy-wootsy and wishy-washy and it makes you roll your eyes at me, fine. I can all-too-well respect that. I am making myself a little bit sick by writing it. But just consider trying it a few times throughout the book, and maybe wonder why the very basic action of physically showing yourself and your body affection makes us cringe. We have a long way to go.

So let’s go.

Welcome to my book. I hope you like it here. We are going to be okay.