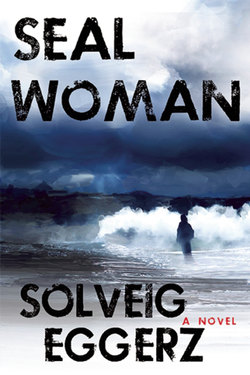

Читать книгу Seal Woman - Solveig Eggerz - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Deepest Landscape Painting

That summer Charlotte had wanted to get back on the boat and return to the ruins of Berlin. But she'd smiled tightly at the other women, then boarded the dusty little bus.

The bus ascended hills, crossed heaths, then ground its gears descending back onto the sands. Charlotte saw how the rain transformed the moss from gray to green. All around her the women chattered in German.

Farmers in Iceland seek strong women who can cook and do farm work.

Like meat needs salt, she'd told her mother. It had to be better than Berlin.

As the bus rattled along the gravel road, she looked for faces in the moss and in the wildflower clusters. The tundra painter had taught her to look for human beings in the grazing land that fingered its way up the side of the mountain, to imagine the shape of bodies in the brown and gold lichens, to see profiles carved in the rock. In her suitcase, she had his book, picked up at a bookstall on the Potsdamer Platz. His wildflowers, lichens, rocks, moss-covered lava made her hungry for this place.

She touched the card in her pocket. It bore the name of her farm, Dark Castle.

The driver stopped.

Sheep's Hollow.

Silence. Each woman checked her card. The dust billowed through the half-open windows, and Charlotte felt the grit in her teeth. Finally, a short, broad-shouldered woman waved her card.

"It's me."

Applause as if the woman had set a new record on the pole vault. From her window, Charlotte watched the lone figure pick her way along the path.

Gisela sat next to her. She was a brunette from Berlin with curls parted and pinned back. Her face dimpled when she laughed in a way that men probably liked. She was from the Wedding district of Berlin, the place where Max had looked for trouble and found it.

"Mine's called Stony Hill," Gisela confided.

On the ship, crossing the Atlantic, the two women had walked the deck together, holding their coat collars high at the neck against the North Atlantic wind. Each day as the ship drew closer to the island, Gisela added details to the hair color of her future five children.

As the bus bounced over the ruts in the road, Gisela leaned against her.

"Remember what I said about a husband?"

Charlotte registered mock surprise.

"I want one," Gisela said. Chirpy as a shopper, she recited her list.

"And three boys and two girls, just like my mother had."

Would it work for her too? Could new humans replace old ones? Charlotte was still pondering these things when the driver stopped and called out the label for her fate.

Dark Castle.

Gisela followed her out.

"You'll write me?" she asked, lips trembling.

Charlotte nodded, watched her only friend on the island disappear inside the bus.

Mountains, meadows, and ocean rolled toward the horizon. The same wind that flattened the grass tingled on Charlotte's cheekbones. Rocks with jagged features, like those of bigboned people, studded the foot of the hillside.

She ran her hands over her hips and looked up at this new sky. She was thirty-nine years old and still alive, a solitary figure in the deepest landscape painting she'd ever seen.

Up ahead, high on the hillside against a gloomy purple mountain, stood a liver-colored farmhouse. She picked up her suitcase, bulging with sweaters knitted by her mother, and walked up the gravel road. Stones stung her feet through the thin shoe soles. As she drew closer to the farmhouse, a small dog with a curled tail burst out of the bright green grass.

At the window, a pale figure lifted a curtain. The door opened, and a man with thick brown hair appeared on the steps. He extended a calloused hand and rolled out the r's of his name.

"Ragnar."

She said her own name slowly, wishing she could explain how her mother had named her after Sophie Charlotte, the elector of Brandenburg's beloved wife who had died young. Usually, the explanation helped her get to know people. But her dictionary was at the bottom of her suitcase.

The dark hallway smelled of sheep's wool and rain gear. She slipped off her gritty shoes and left them next to the pile of rubber footwear. Above the door to the kitchen hung a driftwood painting of a three-gabled farmhouse. Ragnar padded across the floorboards in his socks. Looking too big to be indoors, he said things she barely understood.

Wife's dead. No children.

In the awkward silence, she heard the rub of cloth against the wooden wall. A third person was breathing in the dark hall.

"My mother," Ragnar said.

An old woman with narrow shoulders offered, and quickly withdrew, a slender parched hand, then moved along the wall into the kitchen, her sheepskin shoes swishing over the floor. Ragnar picked up Charlotte's suitcase. She followed him into a small bedroom, dark but for the light from the small window. A chest of drawers stood against the window. A child-sized chair separated the two beds. On it stood a candle next to a book. Egilssaga. She and the old woman would take turns undressing in the narrow space.

When he set the suitcase down on the bed, the comforter made a sound like a person exhaling. At the foot of the bed was a wooden box full of uncarded wool. A carved plank bore words about God's eternal embrace. It hung on the paneled wall above the bed. Making rocking gestures with his arms, Ragnar explained.

From my father's boat. Dead.

Everyone but the three of them seemed to be dead.

The floorboards were splintered and the window casement warped. Above the old woman's bed hung a small oil painting of a farm with a chlorophyll-green home field, next to it a photograph of an ancestor with a stiff priest's ruff.

"Coffee?" he asked.

When she nodded, he looked relieved. Through the thin walls, she heard him talking in the kitchen. A wave of loneliness washed over her. Until this moment she had been moving constantly, caught between then and the future, but now she felt the finality of having arrived. She felt alone like on the day her mother had left her at the new school.

Beyond the open window, earth and sky met at the horizon. She was sealed in. She'd wanted to leave Berlin, not slip off the edge of the earth. But it was not so much a matter of geography as of time. The years of her old life had run out. She swallowed hard.

Here, not there.

Under the neatly folded underwear in her suitcase, she found her old address book and brought it to the window. The names of her classmates were written in a childish script. Her eyes blurred over those who had not survived the war.

Folded up between the pages, she found the advertisement and read it again.

Farmers in Iceland seek strong women who can cook and do farm work.

No mention of companionship, certainly not with this ungainly farmer. Still, his hesitating manner and his stained gray sweater suggested a pleasant humility. Perhaps he'd be more at ease outdoors. She placed her clothes in the chest of drawers. At last there was nothing left in her suitcase but her paintings. No place to hang them in this bedroom.

A shuffle of slippers, and he was back. Smiling awkwardly, he beckoned her to follow him into the kitchen. He seemed to have forgotten about the coffee. Fish sizzled in a pan, and potatoes rattled in a pot. He gestured toward the two place settings. The rest of the table was covered with stacks of bills and receipts. He placed these on the floor, opened the cupboard, and brought out a cracked plate. She sensed this would be her own special plate until it broke or she left.

The old woman gestured toward the steaming fish and potatoes. Then she drizzled a woolly smelling fat over her food. With their eyes on her, Charlotte did the same. Mother and son chewed the saltfish in silence while Charlotte had the feeling she'd interrupted a conversation begun long before she arrived.

There's a hole in the fence out by the main road. That chicken isn't laying.

The old woman dropped her gaze, and Charlotte studied the thick gray braids, looped against her sun-dried neck. The shiny hair appeared to have sucked the juice out of her face.

That night, Charlotte waited in the hall outside the bedroom until the swish of skirts stopped. When she heard the bed boards creak, she tiptoed into the room, slipped off her clothes, laid them at the end of the bed, and crept under the stiff sheets.

A sliver of moonlight revealed the old woman's stony profile, still but for the lips, vibrating with each breath. A cow lowed in the home field. On the moor, a horse neighed.

But sometime in the night, Charlotte's two worlds collided. She hadn't expected the ghost of Max—full of blame and love—to cross the Atlantic, to follow her up the hillside. His lean body pressed against hers in the narrow bed. He whispered about Monet's blues and greens. And she felt safe. But he wouldn't stay the night. When he slipped away into the mist, tears slid down her cheeks and into her ears.