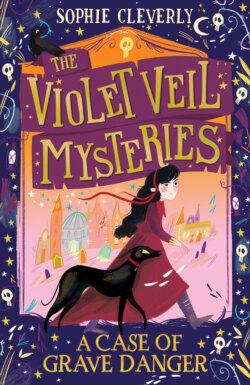

Читать книгу A Case of Grave Danger - Sophie Cleverly - Страница 6

Оглавление

was born in the mortuary. Topsy-turvy, I know, but that’s the truth of it. My mother said the slab was cold and hard, but that she was in no fit state to quarrel at the time.

They named me Violet, for the flower – the twin to my mother’s name, Iris. I think they were hoping I would be a Shrinking Violet, modest and shy, but it was soon apparent that I was not.

My middle name is Victoria, after the queen. They said she was in mourning for her husband these days, roaming the palace dressed only in black. I didn’t see anything unusual about that. Father had clothed us in dark and sombre colours for as long as I could remember. ‘We’re always in mourning for someone,’ he’d say.

Being on the edge of life and death was a funny thing. Sometimes, out among the graves, I could sense the dead. It was just a feeling – an echo of emotion, a scattering of words. It was just a part of me, and I had grown used to it – grown used to keeping quiet about it too, because all I got were strange looks and shushes from grown-ups if I were to mention it.

Often the dead didn’t have much to say. But I was soon to encounter a dead person who had a lot more to say than usual.

The day of the miracle, I had recently turned thirteen years old, and I was out collecting apples in the cemetery. I took a bite of one and it was as crisp as the autumn air. My black greyhound, Bones, ran circles around my feet, sniffing the ground with his long nose.

Bones was a fairly recent addition to the family. I had found him wandering amongst the headstones. As soon as he’d spotted me, he wouldn’t leave me alone. He wore no collar and looked skinny – but then all greyhounds do.

I named him Bones, because growing up as the daughter of an undertaker and living, as we did, beside a graveyard, it just seemed fitting. I fed him scraps and begged Mother to let me keep him. She said no. So I asked Father, who said maybe. Mother finally gave in and said I could have him, but all the same, she made Bones sleep outside.

For two weeks, he slept just beyond our back wall, curled at the foot of a stone cross. By the third week, Mother took pity on him and let him sleep in the back garden. It was only a few days more before he was in the house, and often on my bed.

Now he was my constant companion – at least when he wasn’t distracted by doggy things such as chasing squirrels and chewing shoes.

That day, when my skirts were full of the ripe fruit, I dashed back through the graves and into the parlour – the funeral parlour, that is – leaving Bones rolling in the grass. The breeze whipped my long dark hair across my eyes.

Father was sweeping up when I got in. ‘Honestly, Violet, can’t you use the back door to the house? What if there had been someone in here?’

‘Someone?’ I chuckled. ‘Your guests are usually a little too dead to notice, aren’t they, Father!’

He huffed at me and shook the broom out of the open door. I turned to see Bones trying to get a mouthful of broom before Father tugged it back. ‘And what about the family members? They could be visiting the deceased.’

‘We don’t have any visitors. Not today. I know the arrangements. I do pay attention sometimes, you know.’

‘Really? You surprise me.’ He tousled my hair affectionately and then mopped his brow. ‘What are you going to do with all those apples?’ he asked, but he turned away and I could tell he was no longer paying attention. In the past he would have played with me, juggled the apples, told me some little story about how fruit was somehow a metaphor for life – but he always seemed rather distracted these days.

I looked around the room. My arms were aching with the weight of my skirts, and I suddenly realised I wouldn’t be able to hold on to them much longer, but neither did I want to spill the apples all over the floor.

Aha! There was a coffin on the dais, freshly varnished and upholstered but currently empty. Perfect. I lifted the front of my dress and tipped them all in.

It made quite a racket, as you can probably imagine. That got his attention.

‘VIOLET!’ he shouted, spinning round. ‘Good heavens, girl, whatever do you think you’re doing?’

I grinned at him. ‘I just needed somewhere to put them down for a moment. Don’t worry! I’ll have them out of here before you can spit.’

‘I do not. Wish. To spit,’ he replied.

I realised it was time for a hasty exit. So, with Bones trailing behind me, I scooped up an armful of the red apples and headed through the door into the house.

Mother was in the kitchen, darning some of Thomas’s socks by the fire.

‘Apples!’ I called cheerily.

She looked up and smiled, her bright eyes lighting the room. ‘More apples? I’ll be making a pie or three, then. Add them to the basket in the larder.’

I did as she said. When I returned, she spoke again. ‘You know, my dear old mother used to say that an orchard in a graveyard could only grow bones. How wrong she was!’ She pulled a finished sock from her darning mushroom and tossed it aside. ‘Though we do seem to be overburdened with apples.’ She looked down at the dog. ‘I’m sure this one would prefer a beef bone.’

Bones pricked up his ears and sat wagging his tail, perhaps hoping Mother might actually have one somewhere about her person.

‘You could make a fine bone broth with one,’ I said.

My brother, Thomas, came in just then, his black trousers scuffed at the knees with dirt and grass stains. ‘Yeeuch!’ he exclaimed, throwing his leather football to the floor. ‘Who wants nasty old bone broth?’

Mother reached up and gave him a gentle clip on the ear– he was only six years old, and not yet as tall as me. He was at home for a few weeks after his school had been flooded. I still thought it unfair that he was seven years younger than me, but got to go to school when I didn’t. But then I was a girl and he was a boy and that was just how it was.

‘You’ll eat what you’re given and be thankful, whether it’s broth or five apple pies. We have to make do these days. And look at the state of your trousers!’ Mother was forever having to fix and alter our clothes, whether it was for repairs or to try and keep up with the latest fashions.

Thomas dragged a chair out from under the table, scraping the legs on the floor. Then he sat down heavily on it and ruffled a hand through his dark hair. A few blades of grass fell out. Bones ran over and sniffed them while Mother rolled her eyes at the sight.

I was about to return for more apples (after all, Father would not be pleased if I left them where they were) when Thomas spoke again.

‘Mother,’ he said, ‘who’s to be buried in plot two hundred and thirty-nine?’

Bones looked up at him, his eyes like small galaxies.

Mother put down the darning mushroom and stared at the wall for a moment in thought. ‘Is that one of the new ones? It’s just been dug out?’

‘Yes,’ he replied solemnly.

‘A young man, I think. He came in this morning. No relatives have come forward for him, poor thing. But your father will see to it that he gets a good burial. He always does. Even though it isn’t very good for business.’

I shivered a little, and took hold of a chair-back to steady myself. I remembered the young man she was talking about from earlier. He was fairly tall and pale, with blond hair (a little on the long side). He couldn’t have been much older than me – sixteen, perhaps? I’d sat with him for some time, just talking to him quietly – even the dead need company, though I never heard much back from them when they had recently passed. It was as though they hadn’t settled in yet.

‘Why do you ask, Thomas?’ I said.

He looked up at me. ‘I just wondered. There’s been a few in a row. What if it was murder?’ He made a horrified face. ‘Murder most foul?’

Mother narrowed her eyebrows at him, her favourite look of disapproval. ‘Murders? What nonsense. You’ve got a vivid imagination, my boy. Have you been reading those Penny Dreadfuls again? They are not suitable reading material for a boy of your age.’

Thomas stuck his tongue out, and I covered my mouth with one hand to suppress a giggle.

Mother tutted at him. ‘Your imagination is running away with you,’ she continued. ‘There have just been some nasty accidents, that’s all.’ She went back to her darning.

Bones padded round the table and sat by my feet. I stared into his soulful eyes and, not for the first time, wondered what he was thinking. He had a strange sense for these things, as did I. My skin was beginning to tingle, and I wondered if there was something to Thomas’s bizarre theory. There had been an unusual amount of men in their prime in the past couple of weeks – three or four, I thought. And now this boy. I wondered what could have happened to him. Surely it couldn’t be murder – Father would have noticed.

‘Violet!’ Father was calling me from the funeral parlour. Oops. He was certainly angry now. When I was sure that Mother wasn’t looking, I pulled a grotesque face at Thomas and then headed back down the corridor.

‘Violet,’ he repeated when I entered the room, followed by Bones. ‘Something’s missing.’

‘What?’ I asked. I noticed that he had removed most of the apples already, and began to wonder if the coffin would be the one for the blond boy.

‘One of the files.’

He gestured for me to follow him into the shop at the front of the house (not really a shop in the strictest sense of the word, of course – but death was our business, and money was exchanged here). The shop was filled with gloomy oak furniture – chairs, a desk, bookshelves and row after row of huge filing cabinets that contained all the information about those who were now resident in the cemetery. It was all so dark that I wondered how other people could stand to be in there for any length of time, especially when they had just lost a loved one. Father said it was respectful.

Thankfully, that day the autumn sun was bright and spilled in through the gaps in the heavy curtains. A carriage rattled past outside and a few flecks of dirt splattered on to the glass.

‘It was here,’ said Father. I blinked, my eyes adjusting to the light, and turned to where he was standing. He pointed into one of the drawers in the cabinet.

I walked over and took a look at a row of files. Bones sniffed them curiously. ‘I don’t see anything.’

‘Precisely! It’s missing!’ He wriggled two of the files this way and that with his fingertips. ‘There should be a file here, the one for the boy who came in early this morning.’

I looked at the names written on the top of the paper in my father’s neat hand. All of them read the same: John Doe. ‘The blond boy?’

‘Yes. Did you take it, perhaps?’ He gave me a stern look, and I began to feel a little uneasy. I certainly hadn’t taken it, but under his gaze I felt guilty, as though I had done something. Did he suspect me because he’d seen me talking to the boy as he’d lain there?

I squirmed. ‘No, Father. I haven’t seen the file at all.’

He wrinkled his brow. ‘Well, do you have any idea who might have done?’

I thought about it. ‘Thomas, perhaps? He was asking about the boy just now. He seems to have some theory about murder, but Mother said he’s just been reading too much nonsense.’

There was a moment of silence as Father stared at the wall, and then pushed his spectacles higher up his nose. ‘Thomas,’ he repeated. ‘Of course, I should ask Thomas as well.’ He walked back out of the shop again, in the direction of the house.

I went over to the window and brushed a few cobwebs away. We kept rows of flowers there, tastefully arranged in vases to show what manner of establishment we were. The sign above the door read