Читать книгу The Lost Properties of Love - Sophie Ratcliffe, Sophie Ratcliffe - Страница 19

St Petersburg Station

Оглавлениеl’exécution est de plus en plus difficile … parce que j’ai vidé mon sac

Gustave Flaubert, Correspondances

Anna descends from the night train into the early morning grey, stepping down from the steep carriage stairs and onto the platform of bags and porters and cabs waiting to pick up fares. She would have reached Mockвa at 11 a.m. Moscow Time. (That said, all time was Moscow Time on Russian trains, which meant that if you were on a train near Ekaterinburg wanting blinis for breakfast you could end up being offered a cabbage soup lunch.)

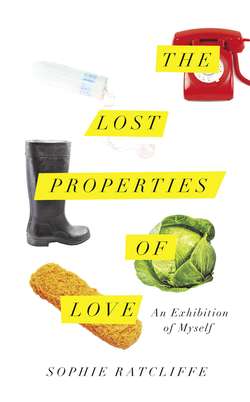

Like all good travellers, she kept her luggage near to her. Standing there, on the platform, in her dark travelling coat and hat, watching the movement at the station, the entrances and exits. She would have had a trunk or two – and a valise. Perhaps a shawl or rug over an arm. And a red silk pouch, her мешочек, would hang from her wrist – just large enough to carry her most immediate possessions. Tolstoy’s wife, Sofia, had three or four bags like this – some beaded, some fabric, some finished with braid, formed in each corner with two loops.

Once you start looking through the novel, bags are all over the place. A rash of them. They break out like measles, all redness and leather, in chapter after chapter. After her first disturbing and thrilling encounter with the handsome officer, Vronsky, Anna hides her face from her sister-in-law’s gaze. She bends her flushed face over a tiny bag, stowing her nightcap and handkerchiefs. Later this is the bag where she keeps her books, the tiny pocket editions of English novels that, in themselves, provide other ways and places to hide. Anna’s handbag is a sign of autonomy. She is a Woman Who Carries Her Own Bag, a prototype of the emancipated New Woman to come. But it is also a sign of retreat. Holding her nightcap and handkerchiefs, the bag is a gathering point – a refuge – and it keeps Anna steady in her attempt to hold herself together. There is, for her, no other gathering point.

So everyday in their status as totes, or carriers, that we barely register their existence, bags are entwined with the world of secrets and power, money and myth. They are not close to our body, like a pocket, nor do they live outside us, like a safe, or a chest. Prosthetic extensions. Intimate, but at arm’s length, the bag is a way of managing space. We condense our stuff, squeeze it into pockets and compartments, shut clasps and buckles and zips – so we can take some of our space with us as we travel. And, unless you’re a fan of transparent handbags (big in the 1960s), they also provide a private space in the public world. Even within our houses, bags usually belong to one individual. We rarely share a bag. They are our bastion, our fortress, our protection from communal space. They are the first place we hide things and the first place you would look to find something hidden.