Читать книгу The Sunshine Crust Baking Factory - Stacy Wakefield - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIII

“Lorenzo came by earlier,” Skip whispered. It was trash night and we were sneaking the bags I’d filled out of the Bakery.

“He did?” I asked, startled to hear the name in my thoughts spoken aloud.

“I told him you were sleeping up on the second floor for now. He put his stuff up there too.”

“I guess that means he’ll be back sometime.” I was totally disappointed. I’d barely left the house in three days. If I hadn’t gone out for food earlier, I could have seen him, asked what was going on.

Skip glanced at me. “You guys aren’t a couple, are you?”

“No.”

“That’s good.”

“Good?”

Skip heaved his bag on top of a neighbor’s broken dresser. He had said that if we added a couple of bags to the piles in front of each building, no one would notice. I shoved mine into the same pile and put a bundle of magazines on top of it and looked up at the building. No movement. We headed back to the house for more.

“Oh yeah, couples are really bad for a group house,” Skip said. “Everyone is equal and friends until there’s a couple. They just agree on everything together.”

“And everyone else is left out.” I thought of my Dad and Angela, how I’d suddenly become a third wheel when they met.

“Exactly. They just want to spend all their time together!”

He sounded perplexed by the thought. I had wondered if he was gay, but now I reconsidered. “You into straight edge?” I asked. I heaved a bag over my shoulder so it rested on my back and we headed up Rodney to Hope Street, where Skip said he’d seen a dumpster.

“Straight what?” He held his own bag awkwardly in front of him so it hit his shins.

“Straight edge? Youth of Today? Minor Threat?”

“I don’t . . . What’s that?”

“Bands, hardcore, you know . . .”

The dumpster was in front of a building under construction. I swung my bag over the edge and we both flinched when it landed, but no lights came on in the dark block. Skip had trouble heaving his in. I got my hands under it and helped push it over. I had at least fifty pounds on wiry little Skip.

“You never heard of Black Flag?” A squatter who didn’t know anything about punk was a surprise to me. “Agnostic Front?”

“Sorry, I’m not hip, I guess. Why did you think I was into that?”

“Oh . . . well . . .” Good question. How had we gotten into this? “What you said about couples, I guess . . . I thought of straight edge. Some straight edge kids are celibate.”

“Celibate?”

“You know . . .” I felt awkward; I was glad Rodney Street was so dark. “Mostly they just don’t drink or do drugs. The idea is being clean so you can, like, think straight. I just thought when you were down on relationships, maybe . . .”

“Are you straight edge?” Skip looked at me as he unlocked the front door.

“No, I don’t call myself that. I don’t eat meat, but . . . I’m not into Krishna or anything.” I shrugged. I had been celibate all summer, but it wasn’t by choice. I pulled more bags out of the first floor and gave the lighter one to Skip. It was so cool he was helping with this gross sweaty work.

I started to thank him as we headed across South 1st but he interrupted, “Hare Krishna? Like the orange robe guys?”

“That scene is totally weird,” I said. I dropped my bag in front of the house directly across the street. We were getting tired, and their pile wasn’t too big. “I don’t get why punk kids would get into Krishna. I think all organized religion is messed up, you know?”

“Exactly! That’s just what I think!” Skip put his bag next to mine and smiled up at the house behind it with his open, defenseless face. “Wow, Sid, it’s really great to have an intellectual around.”

* * *

I decided the second floor needed a mural. The east wall was an expanse of white plaster, empty and inviting. A mural would make the house feel more like a squat. I sat on my sleeping bag and doodled ideas in my sketchbook. If downstairs was where the bakery ovens had once been, this floor must have been used for packaging, with the walls of windows for natural light. There were two small offices at the back with frosted glass doors. Skip lived in one and Eddie in the other. Eddie’s door was open, his radio a drone of baseball. He was lifting weights and every time I looked in his direction, he was grinning at me with his red strained face. I wanted to move my sleeping bag so I was out of his line of sight, but I was worried that would seem rude.

When I had a drawing I liked, I took the lamp over to the plaster wall. I had painted a mural at my high school in Connecticut. The theme was Alice in Wonderland. My friends and I thought the adults wouldn’t get the drug references. We thought we were smarter than everyone else, listening to the Velvet Underground and passing a joint while we painted giant mushrooms and drink-me bottles. That was before I started going to all-ages punk shows. For my friends at school, the Velvet Underground turned into the Doors, then the Grateful Dead. Pot started looking like a gateway drug to shitty music. The hardcore kids I met at shows didn’t care much about drugs either way, they just wanted to save their money for demo tapes and band T-shirts and vegan burritos.

I used a crayon to start sketching on the wall. Eddie came meandering out of his room holding dumbbells to see what I was doing. He hunched on a milk crate doing curls in the dark. Drawing on the white wall with the light on me, it was like I was on stage.

“Who’s winning the game?” I asked to make conversation.

“Huh?”

“Never mind.” I drew a huge egg shape in the center of the wall and then a horizon line. I was sore from working downstairs all week; stretching my arms over my head felt good. The front door creaked open downstairs and I held my breath, listening to the bolt click back in place. I hoped it was Lorenzo, though it didn’t seem likely he had a key yet, and the bouncing steps on the stairs didn’t sound like him, he was more of a trudger.

A lanky boy with Manic Panic red hair burst into the room behind a pizza box. I hadn’t met him yet, but I knew right away it was Jimmy. The ladies’ man, the fashion punk from Ohio, the kind of skate punk with bangs and a Dead Kennedy’s shirt who all the cheerleaders wanted to date in high school. He was hardly ever here at the squat, he spent most nights at the apartments of girlfriends and buddies, wherever there was a PlayStation and food to mooch.

Jimmy cocked his head at me and pulled off his headphones. He gestured at Eddie, who had finished working out and was stretched flat on the dirty floor, arms crossed on his stomach, asleep. “You slip him a mickey or what?”

Skip poked his head out of his room at the sound of Jimmy’s voice.

“Skippy, my man.” Jimmy held up the pizza box. “Check this out! Dudes were closing for the night and gave me all this!” He plopped down on the floor in front of the wall facing me, his long legs spread wide around the pizza box.

Skip padded up in his sports socks, feet turned out like a duck, and introduced me in his formal way. “Sid and her friend Lorenzo are going to be living on the first floor.” I was hungry. I left the circle of light that made the plaster wall look like a stage set and crouched by the pizza box. I picked the pepperoni off a slice.

“Whoa, downstairs!” Jimmy raised his eyebrows, “Total shithole, right?”

“I know you,” I told Jimmy. “I work Donny’s table at ABC.” I’d seen him around but I’d never have pegged him as a squatter. He was too clean and his look was more Sex Pistols than Crass.

Jimmy picked up my discarded pepperoni and ate them while he studied me. But he didn’t recognize me. When you’re fat, you’re invisible. “So, where’s your buddy then?” he asked.

“Um . . . band practice.”

“Ha!” Jimmy snickered. “Leaving the dirty work to you, huh?”

Dirty, you could say that again. We didn’t have running water in the house or a mirror. I’d washed up using my gallon jug of drinking water from the deli, but I didn’t want to waste any. It cost money and I’d just get filthy again tomorrow.

“This drawing is great!” Skip was studying my sketch on the wall. “Wow, you really know how to draw.”

“What’s it supposed to be?” Jimmy asked.

“Giuliani.” I pointed to the egg shape. “See, he’s Humpty Dumpty, sitting on the brick wall. Headed for a fall.”

“What, over there?”

“No, in the middle. His men are the cops over here. They’re going to give that punk in the corner a ticket for drinking beer on the street.”

“It’s looking like a squat in here!” Jimmy laughed. He had finished his slice and now he aimed his crust at Humpty Dumpty’s face. “Take that, Rudy!”

“Jimmy,” Skip said, licking his fingers, “Sid was telling me about how the squats in the city have workdays where everyone works together on house projects.”

Jimmy ripped a piece of crust off another slice and, squinting one eye, aimed for the cops. “Fuck the po-lice!” he chanted like Ice-T.

“Maybe Sunday?” Skip suggested. “What do you think?”

Jimmy looked between him and me like he was trying to think of something funny to say. “What did Mitch say?”

Skip stared at the wall in silence. For some reason the mention of Mitch ended the conversation. I went back to sketching on the wall. Jimmy finished another slice and threw his crust half-heartedly at the cops. It landed on the floor.

Downstairs the door slammed again and we listened to feet coming up the stairs. Mitch, in his basketball sneakers and jeans, rounded the corner and the light caught him dramatically. He and I were spotlit on stage together and no one else spoke, so I waved my crayon and said, “Hiya!”

Mitch’s eyes scanned the wall as he crossed the floor. I felt suddenly silly, like decorating the house, when there was so much real work to do, was frivolous. Mitch’s sneaker hit Jimmy’s pizza crust and he paused a moment to look down.

“You’re gonna get rats in here,” he said. Then he disappeared up the next flight of stairs.

Eddie sighed in his sleep, still stretched out on the floor with his ankles crossed, and we all turned to look at him.

Jimmy unfurled, stretching his arms up to the ceiling. “Hittin’ the hay, comrades!”

Skip said goodnight too, carefully shutting his door. I picked up the box and collected the leftover crusts in it. I took it downstairs before I went to bed.

* * *

In the morning it looked like a moose had ravaged the pizza box. The crusts were gone and the wax paper was shredded into a soft ball of fluff. I shoved the whole mess into a garbage bag and wiped my hands on my shorts. I should have been more grossed out, but I was getting used to it down here.

Mitch appeared in the doorway in a Patriots T-shirt, the messenger bag he took to work slung over his shoulder.

I had all the junk sorted enough that you could walk through the space now, and he followed the path I’d made toward the back wall.

“I’m putting in a woodstove upstairs,” he said, “so save me any wood scraps you got.” He navigated through the room to a closet and moved a rotten piece of plywood. “Bingo! I knew there was a toilet down here!”

I’d built a sort of barricade around the old toilet with tall wood and pieces of metal. We didn’t have running water and it was crusty and gross. Mitch put his bag on the floor and started moving everything.

“You can bucket flush,” he said. “Clean it up and find a bucket. I’ll show you how to get water at the hydrant. You’re gonna be in business.”

I stood back, sure I’d get in his way if I tried to help. “Hey, so Skip and I were talking last night. We want to get a house workday going, you know, maybe work on some projects in communal spaces in the building . . .”

Mitch snorted. He lifted a rusty piece of iron, his arms straining. “I live here ’cause I like to be independent, this isn’t some hippie commune.” He wiped his hands on his jeans. “Everybody should know enough to take care of what needs to get done. If they don’t, they don’t belong here.”

“I just thought it’d be, like . . . cool . . . I mean, being new here . . .”

“So we should sit in a circle and hold hands? Tell our life stories?” He strode out the door swinging his bag over his shoulder. It was easy to end up talking to Mitch’s back. Like I even wanted to hear his stupid life story.

* * *

The door to the laundromat opened and Lorenzo ducked in out of the rain. I dropped the tattered People I was flipping through. Even in the fluorescent-lit tan and orange laundromat the guy managed to look cool. He was wearing a filthy Amebix T-shirt and army pants and leather bands on his wrist. If my T-shirt got that dirty the Latino girls on the street scowled and veered their baby carriages away from me, but on him it looked tough.

“Hey, stranger,” I said as nonchalantly as I could. My heart pounded. “Skip tell you I was here?”

“Yeah.” He sat down a few seats away. “Dude’s all agitated.”

“There was a workday yesterday. At the house.”

“Crap,” Lorenzo said. “Everyone was there?”

“No.” The workday thing was my idea so I was duty-bound to be there and to drink with Skip at the end of the day, since he’d gotten beer and ice to make it festive. I was paying for my forced cheerfulness now, hung over and irritable. “I told Skip you had to work.”

Lorenzo smiled. “Where was everyone else?”

“Mitch thinks he’s too good for group projects. So Jimmy didn’t bother showing his face either. He’s never around, I might add. Really, Mitch is kind of a bully. Skip says—”

“Whoa, tranquilo.” Lorenzo put out a hand to slow me down. “You gotta stay out of that shit.”

Right. Mr. Also-Never-Around. “Seriously,” I insisted, “Mitch is so high and mighty, what’s the point of living in a squat and being all superior like that?”

Lorenzo frowned. “I don’t think he’s someone you want to piss off.”

I got up and looked into my dryer where the blankets I’d found on the street rose and fell. Lorenzo was right, though in reality none of this was what was really upsetting me.

“You wanted a house, right?” Lorenzo said. I could see his reflection in the dryer, his arms stretched casually along the plastic seat backs. “Now what you want?”

My dryer stopped and I stared into it feeling close to tears. What I wanted was for him to be here with me, doing this together, but I couldn’t say that. What right did I have? I was scared I’d only push him away.

“Here, give me.” Lorenzo bundled the blankets together and led the way outside. The rain had slowed to a drizzle. We crossed the street dodging puddles.

“I thought I’d hang the blankets in the doorway,” I said. “Keep the chill out when it gets cold?”

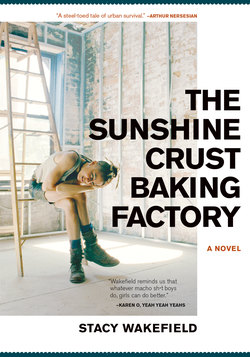

“Good idea.” Lorenzo studied the faded letters painted on the brick while I unlocked the bolt. Sunshine Crust Baking Factory est. 1944.

“The Crust Factory,” he said. “Where’s the crust punks at?”

“I guess that’d be us,” I said and sighed.

“Gotta represent.” He gave me that smile that made everything better.

Inside, I saw he had left a new toolbox by the door.

“Will you look at the window? I can’t get it open.” We went through the maze of crap all the way to the back. The window faced a courtyard next door where a retired cop lived. He was cool, Skip said. He’d told Skip and Eddie about when our house used to be a bakery. He said truck drivers would pull off the BQE at dawn for fresh donuts.

“Was just you and Skip at the workday?” Lorenzo asked.

“And Eddie. But he just stood around like he didn’t want to get his pants dirty. He told us stories about this junkie squat he lived at in Harlem.”

“Yeah?” Lorenzo had WD-40 in his toolbox and big pliers.

“They couldn’t afford nails so they built walls by cutting wood too long so it would just hold wedged together with the tension.”

Lorenzo laughed. “Oh man. We live with the Loony Toons, huh? It okay staying upstairs?”

“It’ll be better when we can move down here.”

“Look, I been busy with my band.” Lorenzo glanced over his shoulder at me. “We got a show in a coupla weeks.”

Here it comes, I thought. He’s bailing. I chewed my lip. Why had I said we like that, like I was depending on him? Why was I complaining about the guys here and making it sound bad?

“After that,” he went on, “I be around more. But man, you kickin’ ass down here.”

“Really?” I breathed out.

“You done a lot. It’s cool.”

It was all worth it. We were going to be together here. Lorenzo grunted with effort and the window opened. There was nothing to look at, it faced a brick building, but a gust of air came into the dank room and we leaned into it.