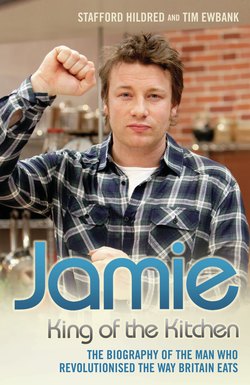

Читать книгу Jamie Oliver: King of the Kitchen - The biography of the man who revolutionised the way Britain eats - Stafford Hildred - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Early Starter

ОглавлениеThe Cricketers, an inviting hostelry in the picturesque village of Clavering, in the heart of rural Essex, is everything an English pub should be. The elegant timber-framed building dates right back to the sixteenth century and inside the atmosphere is warm and welcoming and generally full of highly satisfied customers. This fine freehouse sells a range of good British beers. There is a remarkable wine cellar and the kitchens serve high-quality meals every day of the year. Not surprisingly, licensees Trevor and Sally Oliver are delighted by the recommendations their hospitality and food have produced from the English Tourist Board, Egon Ronay, Michelin, the AA and just about everyone who has ever been fortunate enough to have eaten there. But they also have another production who is doing them rather proud as well, their fast-talking son Jamie.

Today he is internationally famous as the Naked Chef, the television phenomenon who has turned on millions of viewers from Sidcup to Sydney with his delicious high-speed food and high-energy friends in the most refreshing cookery series in decades. But some diners with long memories recall the day when a globally unknown ten-year-old Jamie managed to empty The Cricketers of staff and customers in about five seconds flat.

Bored in the long school summer holidays, he thought it would be a fun idea to let off some stink bombs in the bar. He decided it was sure to amuse his friends from the village who cheerfully sniggered in the background and egged Jamie on. He did not stop for long to consider the consequences, because Jamie Oliver has always been game for a laugh. Never one to shrink from a challenge, the mischievous youngster could not resist completing the dirty deed. Then he and his young pals scarpered as quickly as they could run.

To say that hard-working landlord Trevor Oliver did not see the joke is something of an understatement. Reliable observers of the scene recall that steam was distinctly visible coming from both ears at high speed. Trevor was absolutely furious because the smell was so awful that his customers couldn’t have left any quicker if the place had been on fire. From the moment the first nose twitched over the roast beef to the last diner rushing into the car park took only two or three minutes. It was that bad. Jamie and his pals were watching the scene from behind a fence almost helpless with laughter.

The village chums thought it was the funniest stunt in ages and rushed home to tell their brothers and sisters. Jamie was left with his hilarity swiftly turning to horror as he saw people spluttering and getting into their cars and driving off. Jamie had tears running down his face as he watched the results of his prank unfold before his very eyes. But gradually, even at that early age, the full consequences of his actions were not beyond him. He knew that emptying the pub in record time was bad news for business.

Jamie remembers the result very clearly. He says, ‘Thirty people left without paying and my old man gave me the hiding of my life. If there is one thing in my life I should apologise for it’s that. It was absolutely unforgivable.’

Trevor was furious that his son should be so ridiculously reckless with the family business. He had no hesitation in handing out a suitable punishment to his high-spirited son. But he found it hard to do it without looking Jamie in the eye because he knew that then he would probably burst out laughing.

Trevor Oliver is in possession of precisely the same sort of irrepressible sense of humour as his son. And had the stink bomb attack been mounted on some other establishment, he would most certainly have seen and shared in the joke. But in his own pub, during a busy lunchtime, he could not believe that Jamie could have been so stupid. And it took him some time even to begin to appreciate the funny side.

But it was also extremely untypical. Certainly he might always have been the boy with the wickedly unrestrained sense of humour. But Jamie Oliver is remembered by everyone who knew him growing up as a lad in Clavering as a sunny, good-natured youngster who was full of fun and highly unlikely to commit malicious acts of commercial disaster to his hard-working father.

‘It was a fabulous place to grow up,’ says Jamie, not caring in the slightest how corny this might sound. ‘And I had a wonderful childhood with a wonderful family.’

Villagers were a shade resentful at first of the newcomers who came to take over their local, with little regard for the joys of a late-night lock-in until the early hours. Trevor Oliver was determined to do much more than smile at the few aged regulars who loved to languish over their pints. But he cleaned the old place up from top to bottom and smartened up its appearance, as well as making a whole host of structural improvements.

Yet Trevor and Sally were always very well aware of the impact of all their alterations. They knew they needed to attract new customers who would come to enjoy the growing menu but they still had plenty of time for the locals who regarded The Cricketers as part of the social scene. To this day, they make sure that customers are just as welcome to come and enjoy a leisurely pint or two as those who order a full meal.

The Cricketers remains an integral part of Clavering. It is a quiet, rambling village, happy to be by-passed by busy nearby through-roads like the M11. It is still a place where everyone knows his neighbour and naturally watches out for them. Cars and houses are still often left unlocked. It was certainly an idyllic place to grow up. Even as a child, Jamie was a relentlessly social animal and he was always at the centre of a lively gang of rascals. His earliest memories are of the days when he and his gang used to wander freely around the beautiful countryside. Their time was mainly much more usefully employed scrumping apples or making dens and playing cowboys and indians in the woods. Local farmers knew the lads and turned a blind eye to their activities around the area. Geographically, the village of Clavering might be in Essex but its peaceful unspoilt acres seem a world away from the more familiar image of the urban Essex of Billericay or Basildon.

‘They were never any trouble, those lads,’ said a village elder who asked to be identified simply as Dan. ‘Young Jamie was a very nice lad. When my wife was ill and I was out at work, he knocked on the door one day and asked if she needed anything from the shops. No one told him to do it. He was only 11 or 12 but he knew she was stuck inside all day and he wanted to help. He fetched her some groceries and she reckoned she spent the rest of the day talking to him. My wife was a very good cook and they used to spend hours talking about recipes and meals. She knew some very old country recipes that came down from her mother. They’re not in any cookery books, they were just in her head and Jamie was fascinated by that. He always wanted to know how well a certain meal had gone down at a big occasion and she loved telling him. We never knew another boy who was interested.

‘My wife came from a big farming family in Norfolk and she used to tell Jamie about the great meals they prepared for big occasions like Christmas and when the shoot was on their land. He loved hearing her talk about having to pluck 20 pheasants at the crack of dawn so she could get everything ready for all the “guns” and the “bush-beaters” at night. He was dead inquisitive, was young Jamie, and when I got home she reckoned she was worn out with answering his questions. But he used to come quite a lot after that and he was always full of life and laughter.’

Jamie’s parents originally come from Southend where he was born on 27 May 1975, which was also his father’s twenty-first birthday. He mischievously told one interviewer that he was actually conceived on the end of Southend Pier.

‘I said it for a joke and it ended up in print,’ said Jamie. ‘When it appeared, I had this telephone call from my mum saying, “Everyone will think I’m a slapper.” But I could hear my dad laughing in the background.’

His mum was born Sally Palmer and she used to work in a bank before she met his father and they joined forces in running pubs and restaurants as well as in marriage. The couple are still as devoted today as they were in their courting days.

Sally was first taken by the twinkle in Trevor’s eye and the ease of his warm sense of humour. Trevor was one of many men who took notice of Sally’s blonde good looks and attractive figure. But it was his ability to make her laugh that was the first main attraction.

The Olivers are well known among their friends for having the happiest marriage around. Trevor was delighted when he realised soon after they met that she shared his enthusiasm for building up a good business together. ‘Not everyone wants to work with their husband or wife all day every day,’ says Trevor. ‘Some people enjoy time apart but to Sally and me it has been like a bonus working together.’

Childhood friends are not at all surprised that the marriage has thrived. Trevor always wanted to build up a business and he often talked of one day running his own pub or restaurant. ‘He has always had this amazing drive and confidence in his own ability,’ says one friend from Southend. ‘He believes that anyone can achieve anything if they try hard enough at it. He has no time for whingers and shirkers and people who blame others for their lack of success. I knew he would make something of himself and, when he met and married Sally, I was even more sure. She is like a female version of him. She is very pretty and feminine but underneath she is a really strong, focused woman. And they have hardly changed since they were youngsters.’

Trevor and Sally Oliver’s famously long and happy relationship has influenced Jamie deeply. Even as a boy he noticed that his parents seemed to enjoy life and laugh a lot. ‘They were always really busy, but they always had time for each other and to have a laugh,’ says Jamie. ‘I suppose you couldn’t work that closely together without getting on well but it was more than that. My sister Anna-Marie and I were included in the laughter, and in the pub it always seemed like no one from outside could ever do anything to hurt our little world.’

The Cricketers was completely renovated from top to bottom by the Olivers. They bought the sleepy, shabby old pub when Jamie was still a baby. They knew it would be a long-term project but they could see the potential of the drab and frequently empty village pub in a time when a full range of pub food meant a selection of different-flavoured crisps in many establishments. And, to a huge extent, Jamie has learned from his father’s example.

Jamie’s father is very much his hero and the inspiration for at least some of his boundless self-confidence. ‘Dad taught me to believe that anything is possible,’ says Jamie simply.

‘My old man is a mega hero. He is quite definitely my living example of how to act and how to behave. If he says he will do something then “Boom”. It’s done. I am not as good as that, but I am learning all the time and maybe I am half as good as that.

‘My dad was the true gastro-pub inventor 25 years ago. The Cricketers has been chocker for more than half that time but when he arrived in Clavering the pub was disgusting. It was just a drinkers’ pub with the locals calling in for their pension’s worth of Guinness.’

Jamie’s earliest memories are of watching how hard his parents worked. He noted that some of his young friends had parents who arrived home at five o’clock and slumped in front of the television. Others did not stir from their armchairs all day. With typical indiscretion, Jamie would return home with all sorts of stories of all sorts of more indolent lifestyles. But his father would simply explain his firmly held view that if you want to get anything out of your life, then you have to put something in. Trevor Oliver did not criticise the work-shy of Clavering. The eternal tact of the natural ‘mine host’ taught him not to let the conversation veer towards the controversial. Instead, he preferred to get his message across by example.

The Cricketers certainly gave him plenty of scope for hard work as it was sadly run down when the family arrived. But Trevor and Sally Oliver could see the potential and they had a dream to restore the historic inn to something of its old splendour. And they knew they would never be able to do that on the few rounds of drinks the customers bought. They knew that the future was food and not the third-rate ‘soup in a basket’ style of fare that still predominated in the mid-70s in English pubs. The Olivers wanted to serve the finest meals for miles around.

Jamie grew up watching his parents’ dream come gradually and steadily true. ‘Dad put a menu together, and put a buffet out,’ says Jamie. ‘People would just walk in and walk past at first. But then one person would stop, then two, three, four started to pick up. When I was about six years old, there was a massive turning point. He got a top chef in from Southend and paid him more than he was paying himself and my mum until he got the pub’s reputation up to scratch. He started with 30 covers, moved on to 40 covers and it soon went up and up. After 20 years, he was serving the best pub food in Essex. When I look back, I am pretty proud and impressed by his timing. To me, Dad is the true guru of pub food.’

Trevor Oliver never believed in gimmicks or expensive advertising. He couldn’t afford it and he wanted to build up his business so it became its own best advertisement. Trevor loved to see a customer with a smile on his face. He knew he was a walking advert who would bring in new business. He believed that simple word of mouth could make or break any catering enterprise and he made an enormous effort to deliver good-value, good-quality food at all times. Any rare complaints were dealt with head on. Even when they were being particularly difficult, Trevor knew that the customer was always right. If anyone was not satisfied, they would be dealt with fairly and courteously and often won over with a dish that was more to their taste.

‘We never wanted anyone to leave The Cricketers unhappy,’ says Trevor. ‘I suppose it sounds obvious, but so many businesses seem to regard the customers as a bit of a nuisance. To me, they were the whole point of the exercise. They still are.’

It was like living a lesson in setting up and running your own restaurant and it was the one lesson that attracted young Jamie’s full attention. He reflected later how lucky he was to have such an upbringing. He witnessed first hand the ups and downs of running your own business. And Jamie always loved the social side of the job.

‘Most people are interesting and worth talking to if you approach them the right way,’ he says. ‘My dad was just brilliant at making people feel welcome. He made them feel as if they were valued guests in our home, which in a way I suppose they were. And it’s no surprise that many people who arrived as customers have turned into lifelong friends.’

As he grew up, Jamie gradually realised that one of his father’s great skills was to maintain the same cheery public front out in the pub, even if there was a crisis in the kitchen thanks to a sudden power cut or a chef not turning up for work on time.

Trevor and Sally were well aware that their improvements and changes to the village pub might not get the approval of everyone in Clavering, so they went out of their way to take on board as many of the views of the villagers as possible. There were a few old-fashioned drinkers who were fond of the original pub as a homely hovel, ideal for a quiet pint, but they were steadily won over by the tasteful nature of the alterations and the unfailingly warm welcome they received. And the pub gradually became a key employer in the village as many local youngsters did their first shifts of paid employment under the watchful eye of Trevor Oliver.

In those days, deep in the country and far from any major towns or cities, it was hard to get good fish. It was only delivered on a Tuesday and a Thursday and at The Cricketers they made a big feature of this. Jamie says, ‘I remember my dad shaking his head one day because a woman had complained about the fish. It was as fresh as you like. Even I knew that and I was eight years old. Dad said, “Son, we have to educate some of these people. They are just too used to the frozen stuff.”’

Nowadays, that education seems to be more or less complete and The Cricketers sells fresh fish every day of the week and their customers love it.

The skilled chefs employed at The Cricketers always made their own pasta and even though the theme in the kitchens was traditional English food, everything was done properly under Trevor’s stern control. The steak and kidney pie was made with the help of a half-decent bottle of red wine. The Cricketers has been extremely popular for years now. It took a long time and many hours of careful budgeting to build the business and, at the beginning, money was often very tight.

But Jamie and his sister never wanted for anything and, as the business grew more prosperous, they were always taught to be discreet about the family finances. Some of Jamie’s young friends’ families were very hard up and, even as a youngster, Jamie knew how to be thoughtfully tactful. His father taught him that the really successful restaurant is not about money but about providing an excellent meal and an enjoyable experience to its customers.

Jamie’s mother Sally runs the business side and she is also a very good cook. Sally had a huge influence on Jamie during his formative years and some of his earliest food memories are of her mouth-watering desserts. Sally taught her son to use local ingredients wherever possible and she spent hours with him in the garden or in local hedgerows picking fruit. Years later, Jamie said, ‘I know it’s not rocket science, but blackberries from the bush are never like shop-bought ones in punnets. They always taste so much fresher.’

Jamie loved going with his mum to collect strawberries and raspberries for fruit to make jams and summer puddings and he regularly made himself sick by stuffing more of the succulent fruit into his mouth than their basket.

There is a great catering tradition in the Oliver family and all the relations enjoy nothing more than meeting up over delicious family meals. Two of Jamie’s uncles are cooks, as well as his parents, and all members of the family have a great interest in eating out. They were a very close family and food was at their heart. Jamie loves that traditional Sunday roast family feeling of closeness that was such an integral part of his growing up and tries to incorporate it in his recipes. Nowadays, he says, ‘I’m not changing the world but you have nice times round the table, you know.’ The importance of a family eating together and sharing their thoughts of the day over a well-prepared and leisurely-eaten meal is something which Jamie enjoys and believes in.

Not surprisingly, the catering business interested Jamie from as far back as he can remember. He loved the cheery hustle and bustle of the kitchens and constant throughput of fresh produce being swiftly prepared into tasty-looking meals.

Cooking was something that has been in his blood from a very early age and that caused plenty of disasters. He recalls cheerily, ‘As a kid, I would put things in Mum’s Aga and I would leave them in to cook overnight. When I came back in the morning, they would be like volcanic dust, like you had just cremated your grandmother.’

Sadly for the sake of posterity, Jamie cannot recall in detail the historic first meal that he cooked, though at the same time he can’t remember a time when he was not keen on catering. ‘I was very, very young when I started taking an interest in the kitchen,’ he says. ‘I started cooking regularly when I was about eight as a weekend thing. But when I was really young, my mum taught me how to make an omelette and I found I was good at it. That was a lovely feeling of satisfaction of actually creating something out of something else. I was fascinated by making proper omelettes and for a couple of years that is all I did. Then later, I used to make small pizzas, awful bits of dough, terrible tomatoes and horrible cheese. I used to cook them for my friends when I was about seven or eight. I remember thinking they were excellent but they were horrible! Then I made trifle and it sort of went on from there, really.’

Boyhood friends recall that The Cricketers was an unofficial meeting place for the gang. There was always a glass of lemonade and something delicious to eat.

‘We seemed to be starving most of the time,’ said one early pal, ‘so it was natural for us to congregate where we might get something to eat. Jamie’s dad didn’t like us getting in the way of the customers but if the pub was closed or quiet we used to get in and I don’t think we ever came away without something to eat and drink. It just seemed like such a fun place to be. And the food was always fantastic. Jamie was always trying out new tastes on us. I remember when he brought us some courgettes he was absolutely bursting with enthusiasm for this weird new vegetable that tasted a bit strange to us lot. Only Jamie could get worked up about courgettes. But he also gave us prawns and chicken legs and all sorts of things that we never saw at home. We always seemed to be hungry, so Jamie was always very popular.’

From a very early age, Jamie was desperately keen to join in the camaraderie of the kitchen. To the wide-eyed young boy, the chefs looked like the most glamorous figures in the world. They rushed around shouting out orders and putting together fantastic spreads, usually while having highly animated and unrepeatably rude conversations at very high volume. Jamie did not quite follow the joke, but he joined in the laughter when his father tried memorably to persuade one chef to moderate the language as he asked him with a grin, ‘Why do you have to cook at the top of your voice?’

As an angelic-looking little blond-haired lad, he also got a great deal of attention from the customers. He looked as if butter would not melt in his mouth, but Jamie’s parents were already finding out that their energetic young son was a real handful.

Jamie was just seven years old when he almost drowned in the bath while fearlessly performing a daredevil stunt. ‘My parents had just bought a large corner bath so I decided to try it out,’ he recalls. ‘I went flying along the landing into the bathroom and jumped straight in, but I knocked myself out cold. Mum was getting dressed in her bedroom and she had heard the noise and came to see what was going on. With only half her clothes on, she rushed me downstairs, past all the surprised customers in the restaurant and out to the car. Then she drove me 50 miles to hospital in Cambridge in a complete panic. The doctors said I was concussed yet otherwise none the worse for wear. But I could easily have drowned.’

Even this hair-raising emergency was not enough to persuade Jamie to curb his adventurous, all-action attitude to life. ‘I was a bit wild and I think the first accident might have knocked some of the sense out of me because it happened again,’ said Jamie. ‘Soon after the bath accident, I thought I would try flying because I was the proud owner of a pair of Superman pyjamas. I went hurtling down the stairs and knocked myself out again. This time, however, Mum didn’t waste time taking me to hospital but to the local GP. By the time we arrived at the surgery, I had come round and was sent home after a check-up.’ Jamie says dryly now that he definitely would not want to look after a child like him.

‘When I was younger, I used to dream I could fly. I can recall quite clearly that when I was about five I dreamt of hovering above the sofa. In my vivid imagination, I felt I could float wherever I wanted to go. That led me into all sorts of painful crash landings until I finally realised how hard the ground was!’

Jamie loved living in a busy pub full of people constantly coming and going, and he desperately wanted to join in and become a part of it. His dad and his workers seemed like the most enjoyable gang in the world and he simply could not wait to join it. And even more than that, he wanted to get some pocket money. Cash had a way of burning a hole in Jamie’s pocket that has hardly changed with time. There was always a new toy car or comic that he wanted, so he always seemed to be short of money. Jamie’s father had a very simple and old-fashioned attitude to handing out money. You first have to do some work to earn it. He did not believe in simply handing out cash, even to his children. He believed that handing out endless cash to kids was the wrong way to behave. It taught them nothing about the value of money and it was a certain way to spoil the child. Trevor Oliver is the epitome of a loving father, but he worked very hard to build a better life for his family and he wanted to show his children from their early days that there was a clear link in life between effort and reward.

‘I wanted to have some pocket money to spend and Dad told me that I had to earn it,’ said Jamie. ‘I thought washing up was perhaps not macho enough for a cool and sophisticated eight-year-old. I decided that most of the hardcore action was in the kitchen with the real men and that is where I wanted to be.’

The principle of the paramount importance of hard work on the way to a happy and successful life was thus instilled in Jamie at a very early age. His father made sure both Jamie and his sister Anna-Marie worked for their pocket money because he was convinced it would teach them the value of things.

Jamie has been fascinated by food for as long as he can remember. When he was only eight years old he would find regular employment podding peas, peeling and chipping potatoes and pestering the chefs for more responsible jobs at The Cricketers. He was paid £7.50 for two afternoons’ work and he was delighted. ‘Think how many penny chews you can buy with that.’

Trevor Oliver recalls, ‘Jamie wangled his way into the kitchen, and by the time he was 12 years old or so he was getting to be pretty useful.’ Not that he praised him too highly at the time, for Trevor was always a hard taskmaster when it came to supervising his workers and Jamie was no exception, just because he happened to be his son. But Jamie worked hard and learned aspects of working in the kitchen. His proud father Trevor later noted, ‘When he was still only 14, it was quite usual for him and another chef to cook 100 or 120 meals on a Sunday night.’

Jamie has different memories of his learning curve. He reckons that by the time he was 11 years old he could julienne vegetables like a professional, and when he was only 15, the head chef at the Star in nearby Great Dunmow was confident enough of his culinary abilities that he put him in charge of a section.

Jamie spent a great deal of his boyhood helping out in his father’s pub. Living above the business is not always easy, but Jamie revelled in having his home right at the hub of the village. He loved it always being busy and people coming and going all the time. Jamie is not a solitary person and happily admits that he can quickly tire of his own company if left alone too long. His parents had moved in and took over the inn soon after Jamie was born, so his total childhood was spent in the most social surroundings.

Being brought up on licensed premises has helped to give him a natural ease with people from all walks of life and of all ages. ‘It was quite an amazing experience growing up in a country pub with all these different characters coming in every day,’ he said. ‘There was always something going on and always something happening. We were always taught to smile and be polite to people and make them welcome. So many of my dad’s ways were right, that I find myself following them even now. “People want to feel pleased to be here,” he used to say and I suppose it sounds so obvious. But over the years I’ve seen loads of restaurants where people plainly did not feel pleased to be there. Dad loved his job and he reckoned it was because he was interested in people. “Sometimes it only takes a smile to brighten up a customer’s day,” my dad used to say and many’s the time nowadays that I think how right he was.’

Jamie cannot bear rudeness and slackness in any catering establishment. He seethes when Britain is accused of being second-rate in this department and always speaks up passionately on the country’s behalf.

Jamie loved working in a place where other people were relaxing. His father taught him the importance of listening as well as talking and regulars in Clavering always found young Jamie to be a genial and attentive companion. ‘I would be sitting there talking to old men who would give me a mini-glass of Guinness and I would feel really grown up.’

Jamie was taught early on that customers need to be made to feel comfortable as soon as they enter an eating establishment. ‘If they’ve never been inside before, they might feel a little unsure or awkward and the sooner you can put them at their ease, the sooner they are going to sit down and start enjoying themselves,’ says Jamie. ‘It sounds blindingly obvious, I know. But you can walk into a lot of restaurants and be left standing there like a lemon and it sets completely the wrong tone for the evening. Eating out should be a special experience. My dad drilled into me that people came to The Cricketers to be entertained. Often they were celebrating a birthday or a promotion or an anniversary and if you make that celebration a bit more enjoyable, they are all the more likely to come back again and tell their friends.

‘I suppose I’m lucky because I do genuinely like people, which I have found is a huge help in life,’ says Jamie. ‘Most people have a nice side or something interesting to tell you, if only you take the trouble to find out what it is. And food is such a great leveller. Everyone likes to eat good food, so if you can serve that up to people you are half-way there.’

Customers remember Jamie as an attentive presence around the pub. Bryan Stephenson, a regular who used to drive over from a neighbouring village for supper a couple of times a week, said, ‘Even as a young boy, he was very polite and helpful to the customers. He would come up and ask what we thought of our meal or if we wanted some more pepper or another drink, as if he was really interested in whether or not we were enjoying the meal. He would have a laugh as well but even as a young boy in his early teens he was just like his dad. He had that keenness to please and attention to detail. Lots of people are surprised he has become so famous but I always thought he would do well. He stood out even as a youngster. Good luck to him, I say.’

And Neil Weekes, who played football for Clavering as a young man, remembers Jamie ‘always with a smile on his face. We would go to the pub after the game and Jamie would be helping to serve us our scampi and chips even though he was only about 11 or 12. He was a really nice, friendly lad. The pub had a great family atmosphere. But then, it had a great family running it.’

Jamie’s parents worked very long hours to build up the business but they always tried to cover for each other so one of them was available for the children. Even though they lived above a busy pub, Trevor and Sally were always careful to preserve some privacy and they made sure there was always some special family time scheduled into every day. And they recognised the benefit of having regular family breaks.

‘Being a publican is incredibly hard work,’ says Jamie. ‘You can be on call 24 hours a day and it is hard to ever properly relax. So Dad always made sure that he made the time for us to have proper family holidays. He took us away every single year to the Canary Islands, Cyprus or Madeira just to relax and get spoilt.

‘But the place we always went back to every year was the Norfolk Broads. We used to hire a motor cruiser and go all over the place. Norfolk was fantastic. We would wake up early and there would be mist across the water and it was incredibly peaceful. We would take Nan and Grandad or an uncle or two. It was always good fun. And the boats were cool with pull-out beds, pull-out telly, pull-out oven, pull-out seats, pull-out everything. I found it fascinating. In the mornings Mum would do really good fry-ups for breakfast. Then we would pull back the big roof. It was always a convertible. And I would sit on Dad’s lap and help drive the boat. We would stop at little beaten-up old sheds for free-range eggs “fresh this morning”. The farm would be a mile up the track and they would trust you to put your money in the little pot and everyone always did. Then we’d explore little villages along the way and anchor in a broad, which was like a huge lake, for lunch. We would muck about in the dinghy and swim off the side of the boat and fish for little perch, roach and eels. At the end of each day, we would drop anchor and set up a barbecue in fields by the river. It was great.’

The freedom of the great outdoors has long appealed to Jamie. He loves to have plenty of space and as a boy he would walk for miles around Clavering, building dens, exploring woods and damning up streams. The gang would meet at Jamie’s house to pick up as many supplies as they could snaffle and then set off into the country. Sometimes there would just be two or three, although on occasions there were as many as a dozen of them roaming the countryside. The local farmers knew them all by first names, kept a protective eye on them and gave them their freedom so long as they kept away from the machinery. The link between the people and the land is still strong in a place like Clavering and to this day Jamie is determined to return when he finally tires of the city.

Jamie was generally the leader of the group. He was not exactly bossy but he had a strong personality and a ready wit and he had a natural knack for making the others follow his ideas.

But as he grew older he became more and more involved in The Cricketers. His father came to rely heavily on his cooking skill and his capacity for long hours of hard work. Jamie is very keen to shrug off some of the suggestions that he was some sort of amazing child prodigy in the kitchen. The truth is that he saw cooking at first as just a way of earning some money and helping his dad out at the same time. He liked the work certainly, but insists, ‘I didn’t really become passionate about it until I was about 14 or 15. And I always came second in competitions.’

He never liked that, he admits, as he possesses a fiercely competitive spirit underneath that genial exterior. Jamie smiles, ‘I believe you always have to try to be the best at whatever you do, even if it is scrubbing potatoes.’

Trevor and Sally Oliver were very caring parents but they could be firm, too. And Jamie’s enthusiasm for having long hair was a constant cause of friction. He couldn’t understand why anyone should be allowed to control something so personal as his hair length and they couldn’t understand why he wouldn’t smarten himself up like the other kids.

The bitter conflicts are still clear in Jamie’s memory, ‘My very worst haircut was when I was eight. I had a really cool Ian Brown sort of thing. But then my dad brought two little bruisers in from the tug-of-war team who both had crew-cuts with tramlines and said, “Don’t they look smart?” Two days later, Dad took me to the hairdresser’s, and I had a grade one all over. He’s bald now, though, so I got the last laugh in the end.’

In many ways it was an idyllic childhood, and his early memories are full of tree houses, dens and hilarious fights with soda syphons when the pub was mercifully free of customers. One friend from those days recalls Jamie’s unquenchable enthusiasm for practical jokes. ‘He just loved to throw buckets of water over people. He thought it was the funniest thing in the world to soak another lad to the skin. Once, we hid round a corner, three of us with buckets ready to drench one of our mates. Just as he came round this wall we let fly. Only it wasn’t our friend Dave as we expected, but the village postman. He was quite an old chap and it really took him by surprise. He was wet through and we were so surprised we forgot to scarper. We just stayed there mumbling apologies and in the end he even started to see the funny side. Fortunately, it was quite a warm day and he had almost finished his round so it wasn’t as bad as it could have been. But Jamie was really upset. He likes a laugh but he hates to hurt anyone. Underneath that chirpy, easy-going exterior he is actually a very caring bloke. He was horrified that we had soaked the postie, but then he also knew that if his dad found out he would be in real trouble.’

Jamie loved jokes but he was always dead against doing anything that went too far. Some of the older kids in the village developed the sport of relentless door knocking, bringing residents out to their front doors to discover, of course, that their surprise visitor had already vanished. Jamie was happy enough to watch some of Clavering’s more pompous occupants disturbed this way but he was quick to speak up when an elderly lady who was forced to walk with a frame was targeted. A friend recalls that Jamie was horrified that she was bothered. And when the older boys ran off, he presented himself at the door and asked her if she had any jobs she needed doing. He finished up posting a letter for her and she had her faith in human nature at least briefly restored. And Jamie successfully persuaded her would-be tormentors to leave the poor old dear out of their next round of hilarity.

Three of Jamie’s closest friends as a boy were gypsy children, whose parents were brought to the area by the money to be earned potato picking. It was back-breaking casual work but the potato-pickers did not do it out of choice. Even the kids had to join in and Jamie was horrified when he realised how desperate for cash their families were. Jamie is still friendly with some of those gypsy kids today and neither he nor his parents judged them because they lived life on the move with no fixed address. And although they were sharp and streetwise, Jamie quickly realised his young friends did not even begin to share or comprehend his wide experience of food.

‘They were nice kids but they had such a boring diet,’ he said. ‘They had never even seen decent food, let alone eaten it. The pub closed between three and six and we would be there in the back. I can still picture the scene now. I would be making baps of lettuce, ham and mustard, salami, smoked salmon and lemon and their eyes nearly burst out of their heads. We took it all to a clearing in the woods for a feast. These gypsies had never even tasted turkey and pickle before; they used to just about live on jam sandwiches. Imagine giving them smoked salmon! When I opened up the sarnie and squeezed the lemon on the smoked salmon they just went, “Wow!” That look on their faces was my first feeling of “this is really good” about food that I can remember. It was like showing a kid from 1800 what a VW Golf Convertible looks like.’

But the gypsy kids taught Jamie some things as well. When he went into their caravans, he found families even closer than his own. One particular pal had brothers and sisters of just about every age living happily together in restricted space. Jamie’s abiding memory is of them all speaking at once and hugging and laughing with a warmth and openness of spirit that impressed even the son of an undeniably happy family. Everything was put on the table and shared, he recalls. Whether it was food or money or the spoils of some other unknown enterprise. Jamie once saw them dividing the slices of a loaf of bread equally so everyone had just two. That was all they had for tea but there were no complaints and the evening ended in a very voluble game of cards. Jamie says he has never seen a family with so little have so much in terms of love and affection from each other.

As he grew older, Jamie was keen to learn all elements of the catering trade. His father drilled it into him that running a successful pub or restaurant was not easy. Certainly it involved hard work and long hours but it meant keeping an eye on every aspect of the business. There is no point in serving wonderful meals if you’re losing money on every plate, but if you do not deliver top-quality meals, then the only kind of reputation you’re going to build up is a bad one. Trevor Oliver had his finger on the pulse of every different aspect of his business and he knew that one of the keys to success was buying. Jamie learned the vital importance of sourcing good ingredients first-hand from his hard-working father. He always bought good-quality seasonal fruit and vegetables.

There were a large number of Italian-run greenhouses and market gardens in that part of rural Essex and Trevor Oliver was tireless in tracking them down. He always attempted to get ahead of the game and tried to buy up the best produce before it was sent to market. Jamie gradually graduated to occasional delivery man and remembers, ‘I used to talk to the tomato man on my CB radio. I was Beefburger and he was Ellio the Italian Stallion.’

Trevor built up a good relationship with his suppliers. He paid on time but he would not tolerate any sub-standard produce. The growers came to trust him and, as The Cricketers began to thrive, so the market for their fruit and veg was always there.

In those days, it was not considered remotely fashionable to wear a big white hat and make a lot of noise in the kitchen. And as a career option for style-conscious teenagers, it was certainly not to be taken seriously. Jamie found that he was regularly and mercilessly teased by some of his more conventional classmates for wanting to be a chef. Not that unkindly perhaps, but it was pretty obvious that in those days it was not exactly a cool career, or very macho. ‘It was never a manly thing to do, be a chef,’ recalls Jamie, who refused to have his ambitions even slightly diverted. He has never minded greatly what other people say about him. And nowadays he is, of course, wryly amused that he has the last laugh from what was once considered a joke career. ‘But whether you are a carpenter or painter or a mechanic, you can make the job as exciting as you want. I love cooking. And so I have fun doing it. Now people seem to think it is rather cool.’ The jokes were like water off a duck’s back. ‘Everyone got teased about something,’ he says. ‘I knew my real mates were not laughing at me so I just laughed along with it all.’

All-action Jamie had much more important things to do than worry what a few jealous classmates thought. He was far too busy having a good time. As he grew into his teenage years, fun-loving Jamie was always at the centre of any action. Teachers at Newport Free Grammar School certainly found him quite a handful. One schoolmaster, who prefers to remain anonymous, recalls a concerted campaign involving ‘moving’ pupils. ‘Whenever I turned my back on the class to write on the board, I would hear the furniture start to move around. They seemed to think it was a huge joke to swap seats, and in some cases even desks, while my back was turned. So I would look back at the class and home in on one of the more helpful members of the class, and ask a question to move the lesson on, only to find it was Jamie Oliver, or someone even dimmer, staring balefully back at me. The first time it happened it was most disconcerting. And as young Jamie appeared to be at the centre of it, I appealed to the class one day not to waste precious time indulging in what I described as the “Jamie Oliver Shuffle”. That provoked gales of giggles and the name stuck for a time, though I’m happy to say that from then on they seemed to think I had suffered enough.

‘I have to say that academically it was clear early on that Jamie was never going to be a high flyer. He was not without ability but he loved larking around too much for anything of any substance to remain in his brain. As a boy, he had a face that betrayed just about every one of his impish emotions so you always knew if he was up to something. Board rubbers had an unnerving habit of dropping off the top of doors as you started a lesson when young Jamie was around. He would try to look innocent but his face gave him away. For all that, there was no malice in the lad and I heard more than one story reported back to the staffroom of Jamie and his pals stepping hard on any outbreak of bullying.

‘There was one rather weedy young lad who came on the bus from a village not far from Clavering who was forever getting his sports gear pinched and ink flicked in his face. Today, that bullied youngster is a teacher himself and he told me that it became quite nasty and had him bunking off school to stay out of the clutches of the bullies. But when Jamie and his pals found out about it, they stood up for the lad and warned the older boys off. He didn’t hit anyone, he just stood up to them and issued a few embarrassing remarks about the cowardice of people who pick on people who are smaller than themselves. That did the trick.

‘I always thought Jamie was much brighter than his tests and exam results revealed. He had a gift for talking to people with the sort of honest, wide-eyed enthusiasm that is hard to resist. There is no side to him at all. I met him years after he had left school, just as he was starting to be seen on television, and he seemed to be the same sunny individual I remember shuffling round the classroom. Everyone needs some fun in their lives, even teachers. And Jamie could be relied upon to provide it.’

But Jamie’s knack for getting into scrapes was legendary. Friends used to joke that if you threw a cricket ball up in the school playground it would land on Jamie’s head. And the accident-prone side of his nature was never far away. Jamie had even knocked himself out on a third occasion as a child by crashing his tricycle into a wall. And, much later, he crashed a scrambling bike in a field near his home. ‘My parents didn’t know I was riding that bike as I was only 14 at the time,’ he said. ‘I passed out while I was on it. I think I was overcome by petrol fumes because earlier we had been adjusting the fuel mixture to increase the speed.’

Jamie was born bursting with energy and he has scarcely ever slowed down since. He loved to run across the fields near his home. His parents later moved from the pub to a luxury home three miles away. They wanted to get away from the relentless pressure of living over the shop and Jamie used the journey for regular exercise. ‘I suppose I am lucky that I have always had a lot of energy,’ says Jamie. ‘Running around has never been any problem, I enjoy it. But sitting still is very difficult.’

Once his generous parents introduced Jamie to the concept of regular holidays to spice up a hard-working life he has loved the feeling of getting up, up and away from it all. He loves a quickly-arranged break somewhere new that he has never been before. But even on holiday he found he could manage to land himself in trouble. Jamie remembers, ‘Holidays with my parents ended when I was 14, then school trips took over. I went on two skiing holidays with my class to France. I had already been skiing with my family when I was much younger so I wasn’t a complete novice. We went to a place called Brand in Austria when I was six. At that age, I didn’t seem to have any sense of danger or pain or disaster and my sister Anna and I were skiing in no time. But while Anna glided off elegantly across the mountain, as lovely people should, I just wanted to ski straight down from top to bottom as fast as I possibly could. Even really good skiers couldn’t catch up with me. The following year, Mum said, “You’re making me so worried, you go far too fast. I’ll teach you how to do an emergency stop.” And it was a good thing she did because the very next day I skied like a maniac through this red tape, which obviously meant “Danger”, and I managed to do an emergency stop only a few feet from the edge of a cliff.’

That frighteningly fearless side to his nature used to give his poor parents plenty of anxious moments. They would try to reason carefully with him that he was shortening the span of his natural life expectancy many times over if he continued to refuse to take even a modicum of care. Jamie would nod wisely in agreement and assure them that they were absolutely right – and then continue to live life to its dangerous full at all times.

Jamie sees things slightly differently. ‘By the time I went off with the school, Mum had bollocked me into shape enough to make me concentrate on what I was doing. We went out to France at Easter – 30 boys with a mission not only to ski, but to get hold of drink and fags and do whatever was forbidden, all of us fizzing with pure baby testosterone. It was a wonderful holiday.’

But one thing which Jamie did not instantly appreciate was the delights of European cooking. ‘One thing I learned was that “Continental breakfast” actually meant stale bread and disgusting jam. And on that we were expected to ski for five hours, in theory one of the most demanding sports in the whole wide world,’ he snorted.

As a teenager, Jamie preferred to start the day like most of his contemporaries with a traditional English breakfast – nice crisp fried bread to provide a platform for a couple of eggs and plenty of rashers of bacon alongside. This was definitely not on the menu in the budget accommodation used for the school trips, so Jamie decided to take direct and extremely popular action. ‘So the following year I secretly took a little cooker with me – an old camping gas one – and a non-stick frying pan. We bought bacon and eggs at the local supermarket and did wonderful fry-ups for breakfast on our balcony.’ He laughs loudly at the memory. The hotelier did not appreciate Jamie’s firm rejection of his catering facilities, but he did not find out that the young man had set up his own kitchen on his balcony until it was late in the holiday and he decided to dismiss it as ‘crazy English again’ with a shrug of his shoulders.

Many of the crazes which dominate the waking lives of schoolboys passed Jamie by. His hours were more often filled with hard work or scouring the countryside for adventure than playing with model railways or collecting stamps for an album. He laughs at the very idea. ‘I used to collect beermats as a kid, which wasn’t too much of a challenge for somebody growing up in a pub, but I pretty soon got fed up of that. I mean, what are you supposed to do with beermats when you’ve collected them? Apart from that though, I have never really had a hobby.’

All-action Jamie was never exactly deliberately rash as he hurtled through life, but at the same time he could never claim to be the most safety-conscious person in the kitchen as a young man. At 16, he damaged an artery in his hand in an accident that was very close to cutting short his career as a chef before it had properly begun. ‘I picked up a tea towel that had been used to collect some broken china and a sliver of it severed my artery,’ he remembers with a wince. ‘Surgeons carried out micro-surgery to repair the artery and a damaged nerve and fortunately everything was OK.’

Typically, Jamie chooses to make light of the accident, but it was a terrifying experience for both him and his parents and it has left him with a lasting horror of his own blood and a passion for safety in the kitchen. Jamie is not the least bit squeamish about all the blood and guts he encounters at work, yet certain things can turn his stomach. ‘I’m a bit weird,’ he smiles. ‘If I get a paper cut I faint but I can cut a pig in half and it doesn’t bother me.’

And being accident-prone didn’t just have repercussions for Jamie himself – others suffered on occasions, and did not always recover. He explains, ‘When I was about 13, I had a fish tank with about 250 fish in it. It was beautiful, and when I woke up one morning all the fish had been completely cooked – the thermostat had gone on and all I had was 250 dead fish.’

Young Jamie’s nose would most certainly never be found within the pages of a good book, or even a bad one. He says, ‘Reading bores me to death as I am dyslexic. I have honestly never read a book from cover to cover in my life. And at school textbooks did my head in.’

But Jamie never allowed his dyslexia to become an excuse. He acknowledges that he does not really have the patience or the concentration to become a great reader.

In fact, Jamie admits to an affection for The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole aged 13¾, but insists now the book he has read most often is ‘The Naked Chef, but only because I wrote it and had to check everything so many times’.

When he was younger, he struggled to sit still long enough to spend as long in front of the television as his classmates, but as a young child Jamie never missed The Flumps. Now he has grown up, his favourite Star Wars character is Chewbacca because ‘he makes funny noises and is really hairy’. To this day, Jamie has a very active imagination and loves well-crafted cartoons and slapstick comedy.

Schoolfriends recall Jamie as a very peace-loving guy, but confirm that he is no softie. ‘He was not so much a brave guy as completely fearless,’ says David Stevens, a boy in the year below Jamie at school. ‘I once saw him stand up to three much older boys who were punching one of the juniors in the toilets. It wasn’t desperately vicious, but this young kid was having a hard time.

‘He was a friend of mine and I was standing in the background kind of hoping not to get involved but not wanting to be so cowardly as to actually run away. Jamie came in and saw what was happening straight away. He just walked in front of my friend and looked the biggest guy in the face and said, “That’s enough of that.” And they stopped. There was something in the way he spoke, kind of quiet but confident, that gave the impression that underneath the smiley exterior he might be quite hard. I think the big guy knew him or something and he turned it into a joke and tried to make out it was one big laugh. Jamie laughed as well, but not with his eyes. Me and my mate scarpered but Jamie was our hero after that. He didn’t have to do or say anything and I reckon most people would not have got involved.’

Jamie is convinced that somewhere deep inside him he has the ability to kill someone in extreme circumstances, if someone was attacking him or his family. It was years later when he admitted as much. He cannot remember his valiant schoolboy deeds in standing up to bullies but on a more general theme he is honest enough to admit that if he really had to he could use violence to protect himself and his family.

‘I think everyone has the capacity to kill,’ Jamie said frankly. ‘I think that as you get older and you have a family and kids, you develop a sort of inner love that means you’d do anything to protect them. It would be easy to kill someone if they really threatened the ones you loved.’

Jamie started driving as soon as he could and he loved the freedom of movement that came with passing his test. In a sequence of flashy cars, he quickly became a familiar figure on the lanes and roads around Clavering. His flamboyant style behind the wheel soon earned him the attention of the local constabulary and, as a young driver in Essex, he was nabbed twice for speeding. Only he insists to this day that he wasn’t speeding at all. He believes that the police just haven’t got that much to do out there in the country, so they fill in their time slowing down anyone who looks like a potential speeder.

Jamie and his sister Anna-Marie have always been very close throughout their lives. But they are very different characters. Anna-Marie is famously together and down-to-earth, while Jamie admits he is far and away the more theatrical member of the family. He smiles as he admits, ‘The first day I went to playschool I cried my eyes out and wanted my mummy. On her first day, she got straight in there and started organising people. Some things never change.’

Jamie’s teachers were generally hard pressed to contain his irrepressible sense of mischief and not one of them predicted fame and fortune for the boy who could never ever be persuaded to sit still. Mrs Chris Murphy knew Jamie even before he arrived in her class at Newport Free Grammar School. She remembers, ‘I first met Jamie when he was only three years old and we used to sit in the lovely gardens of his family pub in Clavering with our own children enjoying a relaxing drink in the sunshine.

‘A few years later, I had him as a pupil and taught him on and off for five years after he started in my class in Year Seven. He was 11 years old by then. He was very lively and enthusiastic with an infectious laugh, very much as he is now. I’m a Geography teacher but I also did some reading. To be honest, I never thought he would go far, especially not as far as he has.

‘I knew from The Cricketers where he grew up what a hard worker he was and of his interest in working in the kitchens. But we didn’t do any cookery at school. And I am afraid the truth is that he did not excel at his lessons at all. He was much more interested in the band and in cooking. Jamie was music mad then and I always thought he might do well in that line. But it is very nice when former pupils succeed in whatever field of activity they choose to follow. It’s lovely when you see former pupils do well. Jamie wasn’t very good at spelling. He was in a group where we did puzzles and spelling games to try and improve his spelling. I look at his books and think his spelling is certainly all right now.

‘Then it was an all-boys school. The school has gone mixed since then. And they have food technology now. It was an old traditional grammar school which went comprehensive towards the end of the Seventies. Jamie was a very nice boy and he was always very popular.’

Mrs Murphy is very proud of her old pupil and one of her most treasured possessions is a copy of his first book personally inscribed ‘To Mrs Murphy, all my love, Jamie Oliver’. Mrs Murphy sought out her old pupil at a book-signing session in June 1999.

‘Remember me?’ I asked. “Of course I do,” he laughed as he flung his arms round me. ‘I’ve come for you to sign my book,’ I said. “I still can’t spell,” he admitted.

‘That doesn’t seem to matter very much,’ I replied. My street cred with my present pupils is high as I often use Jamie as a role model for what hard work can do for you in life. And I smile every time I see him on television, which is pretty often. What better motivation can there be for a teacher than a successful pupil, even one who can’t spell?’

As a boy, Jamie used to go and watch his local football team, Cambridge United, but he was never a football fanatic. He loves the comradeship of being in a gang of mates going to a game, but he always used to make sure that they ate before they went because he reckoned the pies were seriously dodgy. Now he is based in London he follows Arsenal, but he does not intend to let it rule his life. And these days, he rarely finds time to go. As he says, ‘Since I have been a professional chef, I don’t get much time to go to matches.’