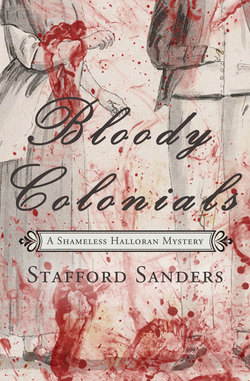

Читать книгу Bloody Colonials - Stafford Sanders - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. LAND HO

ОглавлениеIn other circumstances, the hearty cry of “Land Ho!” ringing out from the throat of a sturdy young sailor, stripped to the waist atop the crow’s nest of a majestic tall ship, might have elicited feelings of excitement, elation or even exhilaration, of a tremendous sense of the achievement of a dream or of the dawning of a life reborn in a bold new world.

In this case, however, all I was able to feel at this exclamation was a rush of numb relief that the interminable blasted journey was finally over and I might soon be back upon dry land at long last.

I hauled my wretched body up from the ship’s railing, having just attempted for the latest of God knows how many times to fill the heaving ocean with the contents of my equally heaving stomach. However, having long since lost the entirety of its contents to previous heavings, no more remained within that chamber to be thus emptied.

As I sagged utterly spent against the railing, that hideous and vivid memory once more came flooding back which had so often plagued me upon this long and gruelling voyage. A vision of similar illness gripping me in the midst of previous duties upon other vessels, important duties which did not brook such interruption. Duties as a naval surgeon, so oft embarrassingly cut short by my forced and rushed departures. Operations abandoned midstream to be salvaged by others whose muttered oaths, shaking heads and disapproving looks had followed me angrily as I had fled those rooms to avoid contaminating my colleagues and my poor patient with the erupting contents of my cursed weak vitals.

There now followed an equally ghastly impression of my poor mother, shaking her grey head in dismay - at yet another graphic and irrefutable report of her son’s abject failure in the line of naval duty.

This in turn was followed by visions of my most recent nightmare: the long months of rolling, pitching, gut-wrenching discontent, confined for what seemed an eternity in the fetid bowels of a vessel tossed like a scrap of debris upon the mighty and utterly unsympathetic seas. My diet during this voyage, of salt beef, flat bread, biscuits and stale vegetables, ameliorated only by the fact that I had kept so very little of it down. The voyage was not, to be sure, the stuff of which dreams are made.

Shaking these wretched recollections from my pounding head, I now slid gracelessly from the rail and dropped to one knee upon the deck. I winced at the painful crack of emaciated bone against hardened timber. Rubbing the bruised knee, I clambered with some effort to my feet, grasping the rail with both hands, and raised my head to blink blearily through reddened eyes. Out over the side of the ship, its immense cream sails already loosened and fluttering, and away through the mist toward the emerging dark shape beyond.

Yes, no mistaking - it was indeed land. To be precise, the Great South Land. The new jewel in the Crown of the British Empire. Not exactly jewel-like now, it loomed up out of the greyness, a dark, low, craggy and eerily indeterminate presence - but it was land nonetheless. I could not suppress a great rasping sigh at the knowledge that at last my gastric torment would be over.

I had arrived at His Majesty’s Colony of Port Fortitude. And, I added to myself with what vehemence I could summon, it was about bloody time.

The problem really started with the Americans. Many problems do seem to start with Americans; but this particular problem was a particular headache for the British Empire in the late eighteenth century - just before this story begins.

The Americans had been part of that great Empire until they turned rather ungratefully against their colonial masters in their impertinent War of Independence – which in 1776 they had the additional temerity to win. They then added insult to insurrection by refusing to allow any more British convicts to be dumped upon what was now, they insisted petulantly, their own sovereign soil.

Damn, thought the British. Now what do we do with all those troublesome convicts? Well, of course we could just hang more of them. That shouldn’t be too hard, since hanging was the penalty for a whole array of offences, most of them well short of serious.

The only problem was an infuriating outbreak of humane jury behaviour. Daunted for some reason by the idea of sending cartloads of offenders off to grisly deaths, modern juries were baulking at convicting on capital charges - preferring to find proven only lesser offences carrying sentences of imprisonment.

Damn again. Now what? Well, how about stuffing them all into the overcrowded, rotting hulks of decommissioned ships floating on the River Thames?

In the long term, this clearly would not do. For one thing, the hulks had begun to breed legions of disease-carrying rats – creatures Londoners were just a little edgy about since the Great Plague. Now the rats were breeding at an even faster rate than the Irish Catholics, who had caught the American disease of rebelliousness (or did the Americans catch theirs?). In any case, their similarly ungrateful uprisings were already producing an increasing proportion of the hulks’ human inhabitants – though in the face of their heroic posturings, it had to be said, most of these Irish convicts were incarcerated not for politics but for petty crimes: stealing, minor assaults and the like.

In any case, the result was: Double Damn.

It was at this point that some bright spark in His Majesty’s Government came up with a seriously original idea: What about sending these prisoners off to the colonies?

Well, yes, of course it had been done before. With the Americans. But this time, it would be different. These prisoners would be sent to the Empire’s safely compliant new South Pacific outpost, the Antipodean continent fortuitously discovered in 1770 by Lieutenant James Cook.

Well, to be precise, Cook was not actually the very first to discover the southern continent: that had been done more than a hundred years earlier by the Dutch - who called it “Terra Australis Incognita”, the “Great Unknown South Land”. So by now it was well past being “Unknown” to the Dutch – and for that matter, to the French, who had also floated in for a bit of a look; and then there were the Macassan traders popping across fairly frequently from the nearby north; and pirates of course, of various nationalities, who had stopped off for one reason or another before moving on in search of serious looting and pillaging - not seeing much worth looting or pillaging in this particular location.

The British could not, however, contemplate recognising or encouraging in any way the achievements of pirates, even less those of Dutchmen or Frenchmen. No, it was Cook, no mistake, who deserved to be credited with the discovery of the South Land, since he was the first to possess the ceremonial presence of mind to actually plant a national flag and claim the place properly for King and Country.

Well, actually, he was not quite the first to do even this. The French had done the planting and claiming thing – but across on the less hospitable western coast; and anyway, they hadn’t followed it up by properly occupying the great island. It remained quite unoccupied when Cook landed in 1770 and quite rightly hoisted the Union Jack.

Well, that is to say, it wasn’t occupied by any civilised people. There were natives there of course – but they didn’t really count as civilised, since they did no apparent sailing about on the high seas, or planting flags, or anything like that. Thus ran the ingenious legal doctrine of “Terra Nullius” – which asserted that if there were no white Europeans living there, then the place was to all intents and purposes uninhabited – meaning Britain was quite within its rights to march in and take it.

While the colonising officers were under instructions to establish “friendly relations” with the indigines, one cannot remain friendly on an indefinite basis with people who refuse to accept their proper subservient position. After all, as one senior chap in the Colonial Office sagely observed, “If the Almighty had intended the blasted natives to have the place, He would have given them the muskets and us the spears and clubs.”

Even worse, He might have given them the lawyers.

So Britain’s First Fleet arrived in the South Land in 1788 to begin the arduous business of establishing a penal colony. Soon more ships followed, as the Mother Country began to see the possibilities of expanding her fledgling outpost beyond mere felonious dumping ground and into potentially prosperous free settlement. Within a decade, British toeholds had begun to spread around the more temperate southern fringes of the continent to virtually all navigable areas of its coastline.

One notable exception was a particular location, passed over by all explorers to date as being quite unsuitable for human habitation.

From the brief accounts available in the Admiralty records, together with various correspondence sent to my mother and myself prior to my rather forced departure, I had been able to glean a certain amount of information upon the history of Port Fortitude. It was not exactly an encouraging read.

The settlement appeared to have been founded quite by accident - and not, it had to be said, in the most auspicious of circumstances.

The colony had its origins in the early autumn of 1800 - when a British naval vessel, the HMS Fortitude, under Captain George Strickleigh, a Master and Commander of apparently questionable mastery and negligible command, had taken a wrong turning somewhere south of Tahiti and finished hundreds of nautical miles away from its intended destination: the established settlement of Sydney Cove.

Caught in one of the sub-tropical storms abounding in that part of the South Pacific, the Fortitude ricocheted gracelessly off one of the many jagged reefs on this portion of the coastline, and ran aground upon a rocky headland – where it sustained a gaping hole in its hull and was soon battered to pieces by the high seas.

Poor Captain Strickleigh was never seen again. It was believed that he had been asleep below – the written accounts provided no further details of this. In any case the surviving crew, together with a handful of hardy (or possibly foolhardy) settlers, and a smallish gaggle of convicts and their guards, managed to stumble ashore and set up camp with enough provisions to ensure their temporary survival.

Word of this soon reached Sydney Cove by means of reports from passing trading vessels. While perhaps wisely unwilling to negotiate the perilous reefs or hazard a nip into the shallow harbour, they at least passed word to the larger settlement of the evidence they had seen from a distance of some living European presence there – a presence which could only have consisted of the survivors of the Fortitude.

The authorities saw this possibility, if true, as quite fortuitous. The inhospitable nature of the place, remarked upon by explorers and traders - its reefs too hazardous, its bay too exposed and too shallow, its soil too sandy, its insects too profuse, and so forth - had meant that the authorities had been so far unable to persuade anyone to establish any kind of settlement there. Indeed, no settlements existed for some distance either to the north or south. Anything to the west, of course, was assumed to be total wilderness and quite uninhabited – except, perhaps, for natives, who were most likely hostile.

The colonial authorities, then, were eager to grasp this new opportunity of gaining another coastal foothold upon the massive continent – since they lived in constant fear of it being taken away from them by the French. Consequently they had rushed an Acting Governor, a small garrison of troops and a contingent of hardened convicts around the coast from Sydney Cove.

They arrived at the starving survivors’ camp in the nick of time, and duly proclaimed it to be from thenceforward His Majesty’s Penal Colony of Port Fortitude.

Slowly, like a local sapling snaking raggedly upwards from sandy soil, the settlement had begun to grow.

Unfortunately, by the time I had read these accounts, and forged from their unwelcoming lines even greater misgivings than I had previously held as to what might await me in this forbidding place, it was altogether too late to turn my mother from her singleminded determination to send me there. I pleaded eloquently, apologised profusely for my past failures, promised sincerely to redouble my efforts, and finally questioned with the greatest respect whether it might not be just a tad excessive to compound an offspring’s failings and to deny him a chance at redemption by condemning him to the probability of an untimely death – whether from the perils of the voyage, or from a native attack, or perhaps from some dreadful tropical disease. Or indeed all of the above.

Alas, it was to no avail. Mother was unmoved and quite resolute. My place in the family heritage must be salvaged, she determined, and salvaged it would be; and if I should perish in the attempt, then it were better to perish bravely than to live on in lily-livered disgrace.

I had no choice, then, but to grit my teeth and accept my fate. I was to be transported to this God-forsaken spot, for - who knows? - possibly the term of my natural life. Given what I had read of Port Fortitude, most likely a term of no great duration.

Still, at least I had survived the blasted voyage. So far, as they say, so good.

On the craggy headland above the grey mist stands a solitary figure – the first to view the arrival of the ship.

She is Polly Dawes, a convict maidservant in plain sturdy working dress, apron and cotton bonnet. She has been up and about already for some hours, rising before daybreak to pump water from the well, to be used in the washing of clothes and the watering of chickens and pigs.

She’s just completed this last chore, and has emerged onto the grassy headland between Government House and the cliffs, full washing basket under one arm, empty scrap tin in one hand, empty water bucket in the other.

Bleedin’ pigs, she thinks with annoyance. Third one this month that’s got out, an’ I don’t suppose we’ll ever see that one again, run off into the bush like the others. So there’s one more dinner that’ll have to be filled out with potatoes an’ greens an’ whatever else we can grow in this rubbish soil. Oh well. Nothin’ to be done.

Now she stops as something in the distance catches her eye. She squints towards the horizon and her eyes widen slightly. She takes a step towards the clifftop and puts down the bucket and tin, one grubby sleeve mopping sweat from her ruddy cheek.

Ah, she nods, the ship is in at last. Its tall, pale sails loom unmistakably up out of the ocean mist as it inches its way slowly around the perilous reef and into the shallow bay.

Polly stands, stares at the ship for a moment, removing her bonnet to swat a stray fly from her cheek. About bleedin’ time too, she thinks. Now maybe we might get some little rise in the food rations at last. Maybe they’ve brought over some more pigs, an’ all.

Well … no point standin’ around here when there’s work to be done, she determines, and no doubt there’ll be a good deal more rushin’ about at Government House once that lot get ashore, what with all the unloadin’ and cartin’ about an what-have-you. All those men with their grand schemes, lots of shoutin’ an’ everythin’s the most important thing that ever there was, an’ it must all be done by about yesterday, or there’s hell to pay. An’ if it’s not done, well, most likely it’ll be some poor convict that gets the blame. She shakes her head slowly.

She turns, leaving the bucket and scrap tin for the moment where they lie in the shallow heath. She gathers her washing basket in both hands, and turns again towards the clothesline.

But as she does so, behind her she hears a noise. No, more than just a noise, a definite and human sort of noise. Well, barely human – and, she shudders, recognising the sound, most decidedly unwelcome. The sound is a low, rasping clearing of the throat, exaggerated to the point of stagecraft. It is a noise that could only come from one person.

Fixing a politely bland expression onto her healthy features and summoning what civility she can muster, Polly turns to face the Reverend Ezekiel Staines, colonial chaplain.

“Mornin’, Reverend”, she intones steadily.

The Chaplain smiles, his ineffectively shaven jowls creasing into a leer above the ever-present off-white clerical collar - which looks very much the worse for having had a number of fluids spilled down the front flaps of it, over the significant period since it appears to have seen any hint of soapy water.

“Lovely morning, my dear”, opines the Reverend in a kind of rasping sing-song - rather akin, thinks Polly, to the sound of a badly-oiled gate. Then he adds with the leer gaining in intensity: “And, I may say, a lovely vision to grace it.” He flutters his eyelashes and almost drools.

My God, she observes with disgust, even his lashes are oily. Over the involuntary turning of her stomach, she forces another barely tolerant half-smile which she works hard to ensure is not accompanied by any visible rolling of the eyes. She satisfies herself with a tone of firm but gentle reproof, trying not to make it sound the least bit playful, coquettish or otherwise encouraging, but merely to truncate further conversation as deftly and politely as possible.

“Now now, Reverend,” she says, in the tone of a kindly but firm governess, “that’ll do.”

And as she turns away from him towards the washing line she adds under her breath, unheard by him: “Pig.”

For a moment the chaplain considers following her; but something in the quiet steel of her rebuff deters him. He narrows his eyes and smiles ruefully, thinking to himself: Bit of a wild one, that one. All that scuttlebutt about the fate that reportedly befell the last man who tried to force his attentions upon her. Had to be shipped home in two separate vessels, according to Halloran the stablehand. Mind you, the Reverend sneers to himself, anything coming from that highly dubious source would need to be taken with a most generous pinch of salt.

Staines shakes his head and watches with ill-disguised prurience Polly’s generous hips swinging backwards and forwards as she pegs the washing out upon the line.

Yes, he thinks, after five years in the colony it is high time I found myself a nice little wife. And then on reflection: But possibly one in need of a little less taming than she. High-spirited, that is the word for her. And while there can be certain … advantages in that, I am not at all sure that she would respond to the requisite degree of discipline from a strong husband and moral guardian such as myself – no matter whether or not the Holy Bible might instruct her that man must rule and woman must obey.

Still, one must not be choosy, he warns himself, what with men outnumbering women in the colony by a proportion of no less than seven or eight to one. Ah, he thinks with a sigh, the many trials cast by the Almighty in the path of us mere mortals.

He ruminates upon this for a moment, takes a deep breath, turns and shuffles away, inspired by his spiritual ponderings to begin a rather tuneless mumbling of one of John Newton’s popular hymns of the time, “The Prodigal Son”:

Afflictions, though they seem severe,

In mercy oft are sent.…

Newton, of course, had been associated with the campaign against slavery – but Staines does not hold this against him. After all, to a good Christian it does seem wrong to haul some poor African half way around the world in the bowels of a ship and turn him into a beast of burden.

No, far better to use the Irish for that. At least they understand what you are yelling at them. Well, almost.

As the Reverend warbles on, his eyes have drifted to the Heavens and away out to sea. All at once he stops, squints into the morning haze. Distant cream shapes flutter majestically into the bay.

Ah, he thinks, the ship has come in at last. His mood brightens immediately at the prospect of the new parishioners this vessel may bring – hopefully a good proportion of them female.

With a great deal more spring in his step now, the Chaplain turns and totters happily off past Government House towards the main street.

Through heavy eyelids half-closed against the bright glare, someone else now observes the ship as it drops anchor out in the bay and the longboats are prepared for the bridging of the remaining distance to the shore.

This observer has only moments ago emerged from the track leading down from the settlement, and now props his ample frame against a navigation post at the top of the dunes overlooking the beach. He puffs with the exertion of this activity as he wipes the sweat from his brow and peers from under a ragged straw hat towards the ship, which sits placidly at anchor in the early morning calm of the bay.

Well now, he thinks, sure an’ that’d be a welcome sight. An’ not before time, too.

He’s reminded of a similar day – must be about just about seven years past now – when he himself arrived on a similar vessel, and from the same port of origin: Portsmouth. He recalls the surge of mixed emotions with which he had at first set foot upon these golden sands. Such a long way, so far from everything he was familiar with. And into a life of such hard labour in such strange surroundings.

Well, he thinks, not all that hard, really, not the way I’ve managed to arrange most of it. At the end o’ the day I’m still standin’, he thinks - unlike some. I’ve not fared all that badly from it, all things considered - not compared with what might’a been. Doesn’t stack up all that bad, really, he concludes, against the hard realities o’ life on the back streets o’ Dublin. Wouldn’t be tradin’ my lot for those back there. Not now.

Still, he thinks, can’t be countin’ me chickens at this point. Not out o’ the woods yet. Still need to be playin’ me cards carefully. ’Specially with what I know about …

His gaze has drifted slowly across the horizon and has run up hard against the dark foot of South Head cliff, its craggy profile standing imposing against the brittle glare.

For one startling moment, there’s a terrible flash in his mind’s eye of a dark shape (or is it two, a larger and a smaller one?) hurtling with a scream towards oblivion. He blinks, rubs his eyes, shudders. The vision is gone.

Now listen, lad, he reprimands himself, don’t you go back there. You get that business well and truly out of yer mind, if you know what’s good for yer. Nothin’ to be gained by mullin’ over that. Nothin’ at all.

He narrows his eyes and directs them purposefully back across the dazzling bay towards the ship. He peers with interest at the longboats. One has set off towards the rough jetty at the southern fringe of the bay just below his position. Wonder who’s comin’ ashore off this one, he thinks. And with an inadvertent licking of the lips: an’ what quality o’ merchandise might be aboard.

He rubs his hands together and starts to whistle a rather comical little tune. Were it more recognisably whistled, it might be identified as an Irish jig.

After what seemed an interminable negotiation of the difficult harbour entrance, the ship had creaked its way slowly and mercifully to a dead halt. It now stood finally at anchor in the large bay.

Several longboats had been lowered alongside and an assortment of ropes and ladders dropped to meet them. I had not dared to watch as with the most remarkable dexterity, the sailors had set to work, conveying luggage and passengers into the boats. I had hung back while most of these had set off for the jetty. I now inched gingerly towards the railing and forced a quick glance downward towards the last of these rather unstable-looking vessels, now bobbing like a cork in the briny in the shade of the ship’s flank, far below where I stood apprehensively awaiting instructions.

I noted with some relief that my own trunk – filled with my clothes, books, medical equipment and assorted other odds and ends - was among the items stacked at the stern of the longboat. Various passengers, having scrambled gleefully down the rope ladder, were now seated therein: a small, motley cluster of settlers of diverse ages, all staring upwards toward the rail of the ship, behind which I remained perched in a state of some reluctance like a long-confined prisoner, pale and skeletal, blinking through the bars towards an uncertain freedom.

“Come on, Doctor, down you come, sir”, shouted a hefty sailor in what he evidently hoped was a confidence-inspiring tone of jovial encouragement; but his voice came from so far below that it gave the impression of rising mockingly from the depths like the cry of some ghostly denizen of Davey Jones’ locker – or indeed Mister Jones himself, inviting the unwary sailor to descend into his watery clutches.

“Down you come”? Easier said than done, I thought. Rope ladders had never been my stock in trade - let alone those dangling from the sides of sea vessels, lurching in sub-tropical swells, into even more wildly lurching and perilously over-laden longboats.

Nevertheless it appeared the thing would have to be done, and better sooner than later. Yes, I determined, best get it over with. Now is the moment, I thought. Yes indeed, I decided, let us without further …

“Come on now, sir! Before the next change of tide, if ye please!” Hoots of laughter from the other sailors and passengers at this.

I gritted my teeth and took firm hold of the ladder with both hands, heaved myself awkwardly over the side and, not daring a seaward glance, started to inch painstakingly downwards, scraping and bumping my already bruised knee against the side of the ship. And bruising the other one to match it, along with both elbows for good measure. In this fashion I made my way towards my destination, bobbing unsteadily such a daunting distance below.

After what seemed hours of diligent scrambling, I had very nearly attained the relative safety of the smaller vessel - when, perhaps a little over-eager to reach it and the promise of dry land beyond, I slipped from the ladder and fell with a squawk and a splash into the swirling water between ship and boat.

I rose paddling wildly to the surface, choking and spluttering, my only thought at this instant being how terribly farcical it was to have survived such a long and gruelling journey, only to drown within a few oarstrokes of the shore. In the rush of water churning around my head I could almost hear Davey’s voice, laughing in mockery: Ha ha, got another one. Down you come, doctor. All the way down.

In the next instant, however, I felt several strong hands grasping my arms and coat, and I was hauled most unceremoniously up over the gunwale and into the longboat. There I lay on my back with my legs kicking helplessly in the air like some half-drowned insect, to the unkind guffaws of sailors and passengers alike.

Slowly I heaved myself onto the end of a box and sat there exhausted and bedraggled, dripping and gasping for breath atop the luggage - as the oars were manned and we set off for the beach. Each new lurch threatened to bring up once more the now merely theoretical contents of my stomach.