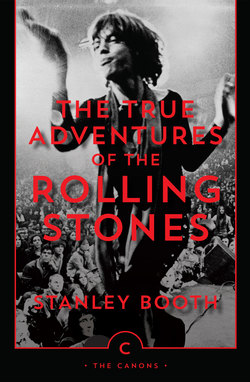

Читать книгу The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones - Stanley Booth - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSIX

One evening there, hot and astonished in the Empire, we discovered ragtime, brought to us by three young Americans: Hedges Brothers and Jacobsen, they called themselves. It was as if we had been still living in the nineteenth century and then suddenly found the twentieth glaring and screaming at us. We were yanked into our own age, fascinating, jungle-haunted, monstrous. We were used to being sung at in music halls in a robust and zestful fashion, but the syncopated frenzy of these three young Americans was something quite different; shining with sweat, they almost hung over the footlights, defying us to resist the rhythm, gradually hypnotising us, chanting and drumming us into another kind of life in which anything might happen.

J. B. PRIESTLEY: The Edwardians

‘So we start talking to Brian,’ Keith said, ‘and he’s moving up to London with his chick and his baby. His second baby, his first one belongs to some other chick. He’s left her and he’s really cuttin’ up in Cheltenham. He can’t stay there any longer, he’s got shotguns coming out of the hills after him, so he’s moving up to town.’

‘He used to come up on the weekends and I’d say, “Look, man, stick it out till you’ve got a bit of bread together, and then come to London,’” Alexis Korner said. Korner, who sang and played guitar, was one of the first Europeans to perform the music of American country blues artists. Brian, after changing from clarinet to alto saxophone and playing in a Cheltenham band called the Ramrods, had become interested in the blues and had begun playing guitar.

‘I’d met Brian,’ Korner said, ‘because while I was working with the Chris Barber band doing odd concerts we played one in Cheltenham and Brian came up to me after the concert and asked if he could speak to me. That’s how we got together. He used to show up at the Ealing club on Thursdays and weekends and occasionally play a bit.

‘Brian couldn’t stand Cheltenham. He simply loathed Cheltenham. He couldn’t stand the restrictions of Cheltenham. He couldn’t stand the restrictions imposed by his family on his thinking and his general behavior. That’s why he came to London, just bang! like that. Every weekend I’d be saying, “For God’s sake, Brian, hold on a bit longer, don’t suddenly arrive in London. It’s a very hard place.” And then in the end one of my weekend chats didn’t do anything and he arrived in London and that was that. One day he said, “I’m leaving Cheltenham and coming to London, can you put me up?” So he arrived, so we put him up. He slept on the floor for a few nights and then he found a place of his own and went to work at Whiteley’s, a store in Queensway.

‘Mick sent me a tape of some stuff he and Keith had got down, odds and ends of Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry numbers. I either answered the letter or we got together by phone, and he came over to my place. Mick was into the club at Ealing almost from the beginning, sort of standing around waiting to sing his three songs every night. If we made any bread, Mick got thirty bob to get back to Dartford on, if not, not. Keith was a very quiet guitar player who used to come up occasionally with Mick from Dartford. He didn’t make every gig but he’d come up most times, and sometimes he’d play and sometimes he wouldn’t. It was a very loose arrangement.

‘In general terms Mick wasn’t a good singer then, just as he isn’t a good singer now, in general terms. But it was the personal thing with Mick, he had a feel of belting a song even if he wasn’t. He had this tremendous personal – which is what the blues is about, more than technique; he’s always had that. I’ve got a very early photo of Mick with a zip-up cardigan and a collar and tie and baggy trousers – Mick always had that, and he had this absolute certainty that he was right.

‘Mick was very edgy, because he was having a lot of arguments with his family. I remember his mother ringing me up one night and saying “We’ve always felt that Mick was the least talented member of the family, do you really think he has any career in music?” I told her that I didn’t think he could possibly fail. She didn’t believe me – she didn’t see how I could make a statement of that sort. I don’t suppose she can to this day. Don’t suppose she’ll ever understand why he is what he is. You know that about someone or you don’t know it, and blood relationship has nothing to do with it. I never met any of Mick’s family. I spoke to his father on the odd occasion, but I find it very difficult to speak to gym instructors. He was a basketball player, I saw him on television once or twice refereeing basketball games. Mick used to come out from Dartford with a sigh of relief as he left and got into the area where he could say what he wanted, which he felt he couldn’t do at home.’

On May 19, 1962, a news item appeared in the music paper Disc, titled ‘Singer Joins Korner’:

A nineteen-year-old Dartford rhythm-and-blues singer, Mick Jagger, has joined Alexis Korner’s group, Blues Inc., and will sing with them regularly on their Saturday night dates at Ealing and Thursday sessions at the Marquee Jazz Club, London.

Jagger, at present completing a course at the London School of Economics, also plays harmonica.

‘In the early summer,’ Keith said, ‘Brian decided to get a band together. So I went round to this rehearsal in a pub called the White Bear, just off Leicester Square by the tube station. Got up there and there’s Stu, this is where Stu comes in.’

Stu – Ian Stewart, a boogie-woogie piano player – comes from a Scottish town just north of England, Pittenweem, Fife. ‘I’d always wanted to play this style of piano,’ Stu said, ‘’cause I’d always been potty on Albert Ammons. The BBC used to have jazz programs every night, and one night many years ago my ears were opened. I’d thought boogie was a piano solo stuff, and they had this program called “Chicago Blues.” I don’t remember any of the records, all I can remember is that they had this style of piano playing with guitars, harmonicas, and a guy singing. So when a little advert appeared in Jazz News – a character called Brian Jones wanted to form an R&B group – I went along and saw him. I’ll never forget, he had this Howlin’ Wolf album goin’, I’d never heard anything like it. I thought, Right, this is it. He said, “We’re gonna have a rehearsal.”’

‘We have one rehearsal which is a bummer,’ Keith said, ‘with Stu, Brian, a guitar player called Geoff somebody, oh garn what was his name, and a singer and harp player called – we used to call him ‘Walk On,’ that was the only song he knew. He was a real throwback, greasy ginger hair. These two cats don’t like me ’cause they think I’m playing rock and roll. Which I am, but they don’t like it. Stu loves it ’cause it swings, and Brian digs it. Brian doesn’t know what to do, whether to kick me out and keep it together with these cats or kick those two out and have only half a band again. Nobody is even thinking yet of actually playing for the audience. Everybody’s still very much into rehearsing together and playing together just to try to get it together and find out whether you’ll ever get anywhere near it. Brian was working. He had a job in a record store. After being thrown out of another for nicking something or other. He decides to get rid of these two cats, which is all right with me, and meanwhile I persuaded Mick to come to rehearsal, which is now going to consist of Stu, me, Mick, Brian, and Dick Taylor on bass, no drummer. Piano, two guitars, harmonica, and bass. Mick starts learning to play harmonica. We get this other pub for rehearsals, the Bricklayers’ Arms in Berwick Street. We had a rehearsal up there and it was great, really dug it. It was probably terrible. But it swung and we had a good time. Most of the pubs round the West End have a room upstairs or in the back which they rent off to anybody for five bob an hour or fifteen bob a night. Just a room, might have a piano in it, but nothing else, bare floorboards and a piano. Cardboard boxes full of empty bottles. That was virtually home for the rest of the summer. We’d rehearse twice a week, no gigs. The first fans if I remember appeared on the scene at this point. I left art school during this period. I did try for one job with my little portfolio, and I was promptly turned down by the cat who designed the cover for Let It Bleed. Mick meanwhile still singing with Korner, to make a little bread and ’cause he dug it. Brian was living right in the middle of where all the spades live here, in a basement, very decrepit place with mushrooms and fungus growing out of the walls, with Pat and his kid. Now sometime this summer something really weird happens. One night Mick, who’d been playin’ a gig with Korner, went round to see Brian, if I remember rightly, and Brian wasn’t there but his old lady was. Mick was very drunk, and he screwed her . . . This caused a whole trauma, at first Brian was terribly offended, the chick split, but what it really did was put Mick and Brian very tight together, because it put them through a whole emotional scene and they really got into each other, and they became very close . . . so that kind of knitted things together. Mick was still very strongly into school, music was just a sort of absorbing hobby, nobody was taking it seriously except Brian, who was really deadly serious about it.’

After Brian’s death, Alexis Korner’s wife went into Whiteley’s, Brian’s first employer in London, ‘and suggested,’ Korner said, ‘they erect a plaque. They were absolutely shocked. She said, “On houses where famous men have lived they put up plaques saying Charles Dickens 1860, or whatever, I don’t see why you shouldn’t put up a plaque in the electrical department saying Brian Jones worked here in 1962, I can’t see any reason why you shouldn’t.’”