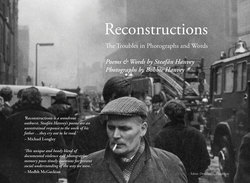

Читать книгу Reconstructions - Steafán Hanvey - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

A few years back, my father emailed me a black-and-white photograph of Main Street in Brookeborough, his home village in Co. Fermanagh. I used to spend my Easter holidays and some of my summer holidays down at my Granny Hanvey’s in the same village. She would often mistakenly refer to me as ‘Bobbie’ – my father’s name – to which I passed little heed. I never let on, for I knew, even as a child, that she’d just mixed us up, and to put her right, I thought, would have embarrassed us both no end. So, I just went by ‘Bobbie’ when I was staying with her. To the local kids, I was known as ‘Hansy’s cub’. To complicate matters even further, when I saw photos of my da as a child, I thought they were of me; so much so, that I wouldn’t believe my parents or my granny when they tried to convince me otherwise. This close resemblance made more sense of my granny’s mix-up. To her, having me around, was like having her Bobbie back. It was clear she missed him terribly and that she was very lonely, having become a widow several years earlier. So, I was really company for her in her later years, something I’m glad of when I look back.

Getting back to the photograph of Brookeborough: no sooner had I received it than I had written a poem about my stays with Granny Hanvey. Within twenty minutes, I’d sent it back to my father. I was aware that I had a collection of memories that would have been very similar to his own as a child. Perhaps I was trying to impress upon him our shared experience. Happily, he reacted positively and the idea for this book was born.

Having just one month earlier become a father myself for the first time, I was enjoying a breather from a prolonged period of touring my second album Nuclear Family and its artistic corollary, a multimedia performance called Look Behind You!™ A Father and Son’s Impressions of the Troubles through Photograph and Song, which happily brought my father’s work to new and distant audiences.

Curating, producing and eventually touring Look Behind You!™ had shown me that I had several channels of expression before me. Things were opening up, even if words were still the primary focus. Quite surprised at how easily the memories made their way down the pen and onto the page, I thought it would be an interesting and challenging project to embark upon, so I got writing. Although I had been working with words in one form or another for most of my life, this experiment and process proved to be a different animal altogether – different to anything I had previously tried or produced. I then started to revisit some of my father’s iconic photographs with the intention of producing a poem for each. In the end, the photos were part-inspiration, part-confirmation, in that I reacted to some and wrote new poems, whereas others complemented pieces I’d written at earlier stages of my life.

Growing up in the house anomaly built meant that I was present at the conception of many of these photographs. I witnessed their act of becoming, as it were, and marvelled as they developed a life of their own in chemical trays. I pegged many of them on the drying-line myself and often had a hand in the framing before they took up residency on the walls of our home.

Sometimes, after having been out in the wee hours on the latest adventure, I’d put the photographs on the day’s first buses to their pre-arranged collection point, ready for whatever newspapers happened to be carrying them that day. I watched them take on other lives too – on book covers, inside the books themselves, and on record covers. I witnessed and partook in captions in the making, photographs of me and us all in the taking.

My point is, they were there as much for me growing up as I was for them and now that they’ve found a new virtual home in an archive in Boston Mass., I thought I’d take a torchlight and blow a layer of dust off and say to the world, ‘Look, over here! This is something to see!’ And look they did, and they’re still looking.

We all look at photographs differently; we see new things every time we revisit them, details we may have missed first time around, which I suppose is why we have the phrase ‘one look is worth a thousand words’.

It’s clear who pressed the button. My father has likened the capture itself to a sniper pulling a trigger: ‘You look through the camera the same way a sniper looks through a gun. You press the shutter, he presses the trigger. He hopes to get something. I don’t think there’s much else involved.’ He conceived these photographs and I hope that my words, responses and memories do them and their taker – my fathographer – the justice they deserve. I also hope that in my presentation of each reconstruction that I have afforded the less-fortunate – those who lost their lives, and those who were hurt and are hurting still – their due respect.

This is my first collection of poems.

Steafán Hanvey, 2018