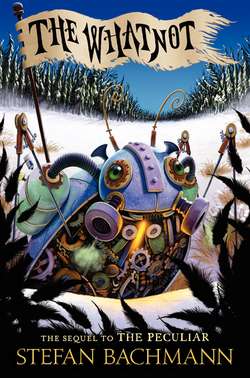

Читать книгу The Whatnot - Stefan Bachmann - Страница 7

Оглавление

IX days and six nights Hettie and the faery butler had walked under the leafless branches of the Old Country, and still the cottage looked no closer than when they had first laid eyes on it.

Of course, Hettie didn’t know if it had been six nights. It always felt like night in this place, or at least a gray sort of evening. The sky was always gloomy. The moon faded and grew, but it never went away. She trudged after the wool-jacketed faery, over roots and snowdrifts, and the little stone cottage remained in the distance, unreachable. A light burned in its window. The black trees formed a small clearing around it. Sometimes Hettie thought she saw smoke rising from the chimney, but whenever she really looked, there was nothing there.

“Where are we going?” she demanded, for the hundredth time since their arrival. She made her voice hard and flat so that the faery butler wouldn’t think she was frightened. He better think she could smack him if she wanted to. He better.

The faery ignored her. He walked on, coattails flapping in the wind.

Hettie glared and kicked a spray of snow after him. Sometimes she wondered if he even knew. She suspected he didn’t. She suspected that behind the clockwork that encased one side of his face, behind the cogs and the green glass goggle, he was just as lost and afraid as she was. But she didn’t feel sorry for him. Stupid faery. It was his fault she was here. His fault she hadn’t jumped when her brother Bartholomew had shouted for her. She might have leaped to safety that night in Wapping, leaped back into the warehouse and England. She might have gone home.

She wrapped her arms around herself, feeling the red lines through the sleeves of her nightgown, feeling the imprints the faeries had put there so she could be a door. Home. The word made her want to cry. She pictured Mother sitting on her chair in their rooms in Old Crow Alley, head in her hands. She pictured Bartholomew, the coal scuttle, the cupboard bed. The herbs, drying above the potbellied stove. Pumpkin in her checkered dress. Stupid faeries. Stupid butler and stupid Mr. Lickerish and stupid doorways that led into other places and didn’t let you out again.

She paused to catch her breath and noticed she had been clamping her teeth shut so hard they hurt. She wiped her nose on the back of her hand and looked up.

The cottage was still far away. The woods were very quiet. The faery butler barely made any sound at all as he walked, and when Hettie’s own loud feet had stopped, the whole snowbound world seemed utterly silent.

She squinted, straining to make out the details of the cottage. There was something about it. Something not right. The light in the window did nothing to dispel the hollow, deserted look of the place. And the way the trees seemed to curl away from it … She closed her eyes, listening to her heartbeat and the whispering wind. She imagined walking forward under the trees, hurrying and spinning, gathering speed. Her back was to the cottage. Then she was facing it, and for an instant she was sure it was not a house at all, but a rusting, toothy mousetrap with a candle burning in it, winking, like a lure.

“Come on.” The faery butler was at her side, dragging her along. “We haven’t got all of forever. Come on, I say!”

She stumbled after him. The cottage was normal again, silent and forbidding in its clearing.

“I can walk by myself,” Hettie snapped, jerking away her arm. But she was careful not to stray too far from his side. They really didn’t have all of forever. In fact, Hettie wondered how much longer they could go on like this. They had nothing to eat but the powdery gray mushrooms that grew in the hollows of the trees, and even those were becoming scarcer as they went. There were no streams in this wood, so all they had to drink was the snow. They melted it in their hands and licked the icy water as it ran over their wrists. It tasted of earth and made Hettie’s teeth chatter, but it was better than no water at all.

Hettie crossed another snarl of black roots, stomped over another stretch of crusty snow. She was so hungry. She was used to that from Bath, but there it was different. Her mother was in Bath, washing and scrubbing and making cabbage tea, and Hettie had always known that she’d never let her and Bartholomew starve. Hettie doubted the faery butler would care much if she starved to death. He didn’t give her anything. He hadn’t told her to eat the mushrooms or melt the snow. She had watched him and had stuck her nose up at him, and then she had gotten so hungry she’d had to copy him. But what would happen when there were no mushrooms left? What would happen when the snow all melted?

When she felt she couldn’t walk another step, she stopped.

“I’m tired,” she said in the sharp, nettled voice that back home would have gotten her a pat on the head from Mother and a silly face from Barthy. “Let’s stop. Let’s stay here for tonight. We’re not getting any closer to that dumpy old house and I want to sleep.”

The faery kept walking. He didn’t even glance back.

She bounded after him. “You know, what if someone lives in that cottage? Have you thought about that? And what if they don’t like us? What’ll happen then?”

The faery kept his eyes locked straight ahead. “I suspect we’ll die. Of boredom. I’ve heard tell there’s a little girl in these woods, and she follows folk about and jabbers at them until their ears shrivel up and they go deaf.”

Hettie slowed, frowning at the faery’s back. She hoped he would drown in a bog.

She thought about that for a while. If he did—drown in a bog—it would be frightening. He would lie under the water, and his long white face and white hands would be all that showed out of the murk. And perhaps his green eye, too, glowing even a thousand years after he was dead. She wouldn’t want to see it, but she didn’t suppose she would object much if it happened. This was his fault, after all.

Finally, when even the faery butler was breathless and dragging his feet, they stopped. Hettie collapsed in a heap in the snow. The faery butler sat against a tree. The woods were dead-dark now. On her first night in the Old Country, Hettie had slept against a tree, too, thinking that the roots might be warmer than the ground, trees being alive and all. She soon learned better. The trees here weren’t like English trees. They weren’t rough and mossy like the oak in Scattercopper Lane. They were cold and smooth as polished stone, and she had woken with the ghastly feeling that the roots had begun to wrap around her while she slept, as if to swallow her up.

The snow was cold, but at least she was not in danger of being eaten by a tree. She curled up for the seventh time and went to sleep.

The sound of footfalls woke her.

At first she thought the faery butler must be up again, pacing, but when she peered around the tree, she saw he was lying still. His gangly legs were propped up akimbo, long white hands limp in the snow. He made only very small sounds as he slept, little wheezing breaths that formed clouds in the air.

Hettie sat bolt upright. Something was moving through the trees, quickly and stealthily toward them.

Tap-tap, snick-snick. Hard little feet on roots, then on snow, limping closer.

She remembered the faeries she had seen the day they had arrived in the Old Country, the wild, hungry ones with their round, bright eyes. They had all leaped and swarmed around her, poking and prodding until the faery butler had chased them off with a knife. For a few nights they had followed, slinking along at the edge of sight, darting around the trees and giggling, but after a while they had seemed to tire of the strangers and had vanished back into the woods.

Only the cottage remained.

Hettie crawled around the tree trunk. The faery butler was still asleep. She poked him in his ribs, hard.

He grunted. Slowly his face turned toward her, but his eye remained shut. The green-glass one was dull, tarnished lenses loose across its frame. Hettie shivered.

She looked back around the tree.

And found herself staring straight into the red-coal eyes of a gray and peeling face.

“Meshvilla getu?” it said, and placed one long finger to its lips.

Hettie made a little noise in her throat. The skin of its cheeks curled like ash from a burned-up log. Its breath was cold, colder than the air. It blew against her, and she could feel it freezing in a slick sheen on her nose. It smelled rotten, wet, like a slimy gutter.

“Meshvilla?”

She wanted to run, to scream. Panic welled in her lungs. She couldn’t tell if the gray thing’s voice was threatening or wheedling, but it was without doubt a dark voice, a quiet, windy voice that prickled up her arms.

“No,” she squeaked, because back in Bath that had always been the right answer for changelings like her. “No, go away.”

The creature pushed closer, eyeing her. Then its horrid hands were feeling over her cheeks, running through the branches that grew from her head. Bone-cold fingers came to rest on her eyes.

Hettie screamed. She screamed louder than she had ever screamed in her life, but in that vast black forest it was just a little baby’s wail. It was enough to wake the faery butler, though. He sat up with a start, green clockwork eye clicking to life. It swiveled once, focused on the gray-faced faery.

The faery butler jerked himself to his feet. “Valentu! Ismeltik relisanyel?”

The gray face turned, its teeth bared. Hettie heard it hiss. “Misalka,” it said. “Englisher. Leave her. Leave her to me.”

Hettie began to shake. The long, cold fingers were pressing down. An ache sprang up behind her eyes. She knew she should fight, lash out with all her might, but she could not make herself move.

The faery butler had no such troubles. A knife dropped from inside his sleeve and he swung it in a brilliant arc toward the other faery, who let out a grunt of surprise. It was all Hettie needed. She threw herself to the ground and began to crawl desperately around the base of the tree. Once on the other side, she wrapped her arms around the trunk and peered in terror at the battling faeries.

They moved back and forth across the snow, swift and silent. The faery butler was fast. Faster than rain. She had seen him fight back in London, seen him use that cruel knife on Bartholomew, but right now she was glad for his skill. He moved his long limbs with grace, whirling and slashing, liquid in the moonlight. The blade spun, streaking down over and over again toward the other faery, who barely managed to get out of its path.

“No!” it screamed, in English. “You fool and traitor, what are you—?”

The knife grazed it. Bits of gray skin flew away on the wind. Hettie saw that underneath there was only black, like new coal.

She turned her face into the tree, squeezing her eyes shut. She heard a shriek, a dull thud. Then a whispering sound and a long, long breath fading away. After that, there was nothing.

It was a long time before Hettie dared peek around the trunk. She listened to the faery butler, pacing in the snow and panting. She wondered if she should say something to him, but she didn’t dare do that either. He seemed suddenly frightening and dangerous. After a while she heard him lean against the tree, and after another while, his slow, whistling breaths. Only then did she inch from her hiding place.

The faery butler was still again, his green eye dark. The snow between the roots was trampled. At the faery’s feet lay what looked like a heap of ashes and old clothes. Already they sparkled with frost.

She edged over to the heap. It didn’t look like a faery anymore. It didn’t look like anything, really. Nothing to be afraid of. She nudged the pile with her toe. It rustled and gave way, the jerkin and boots collapsing over a delicate shell of cinders.

She wondered what sort of creature it had been. She didn’t know if it had been a woman-faery or a man-faery. She had never seen a faery like it in Bath, falling to ashes.

The moon was out like every night, and it shone through the branches, glinting on something in the clothes. Hettie knelt and shuffled about in the pile. Her fingers touched warmth. She jerked back, wiping her hand violently on her sleeve. Blood? Was it blood? But it couldn’t be. If there was frost, the blood would have gone cold by now. She leaned in again, brushing away the rest of the ashes with the hem of her nightgown. Her hand closed around the warmth. She brought it up to her eye, examining it … and found herself looking into another eye—a wet, brown eye with a black pupil.

Hettie let out a muffled shriek. She almost dropped it. But it was only a necklace. The eye was some sort of stone, set into a pendant, a pockmarked disk on a frail chain. The pendant lay heavily in her palm, the warmth seeping into her fingers.

She stared at it. She hadn’t felt anything warm in so long. She ran her thumb over the stone. It looked precisely like a human eye. There was even a spark in it, a knowing little light like the sort in a real person’s eye. She couldn’t tell what its expression was, because there were no eyebrows or face to go with it, but she thought it looked sad somehow. Lonely.

She peered even closer.

Behind her the faery butler shifted, white hands scraping over the snow. Somewhere in the woods, branches skittered.

Hettie tucked the pendant into the neck of her dress and darted back around the tree. She went to sleep then, and the eye kept her warm the whole night long.

The next morning, when she woke, the forest seemed to have lightened several shades, fading, like the pictures on coffee tins when they were left too long in the sun. The clouds no longer hung so low in the sky. The trees didn’t look so close together. The cottage was still a hundred strides away, but when Hettie and the faery butler took their first step toward it, it was quite distinctly only ninety-nine. A short while later they were halfway there.

No light burned in the window anymore. The door hung open on its hinges, showing blackness. The house appeared even emptier and more desolate than before.

When they were only a few steps away, Hettie glanced back over her shoulder. What she saw made her whirl all the way around and stare.

Their footprints extended back in a thin line into the woods. And then the forest floor became packed with them. Thousands upon thousands of prints, winding between the trees—her small ones, and the faery butler’s long, narrow ones—going back and forth and round and round, trampling one another and never arriving anywhere.

A tangle of footprints under the very same trees.