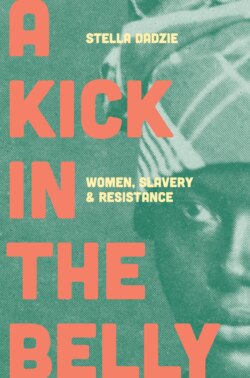

Читать книгу A Kick in the Belly - Stella Dadzie - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

A Terrible Crying: Women and the Africa Trade

There were many women who filled the air with heart-rending cries which could hardly be drowned by the drums.

Ship’s surgeon, 1693

There is no way to tell this horror story in a palatable way. Perhaps, if the descendants of those who benefited most had made recompense for this dark chapter in our shared history, it would be easier to talk about. But the legacies of those centuries of genocide and abuse are still with us, in relative levels of poverty and education, infant mortality and prison occupancy rates, wars, human suffering and a plethora of other glaring North-South inequalities, both social and economic, that cry out for reparation.

For all of this, it was never a straightforward black-white issue, and who owes what to whom is an ongoing debate. The trade in captured Africans was a complex transaction and Europeans were responsible for every aspect of its execution, yet the unpalatable truth is that it could never have survived or prospered without significant African involvement. But if some Africans colluded in the theft and sale of their own people, the evidence shows that there were also countless others who found the courage and the means to fight back, despite every effort to quash their human spirit.

This is the thought that preoccupies me as I step down into the dungeons of Elmina Castle in Ghana, Portugal’s first African trading fort. Built in 1482, it is an enduring monument to one of history’s most shameful epochs. In the holding cells, more than two centuries after Britain officially abolished the Atlantic slave trade, the stench of hundreds of thousands of captives still clings to the walls.

In the sun-scorched courtyard, a solitary cannonball too heavy to lift marks the start of our guided tour. Our guide describes how women who declined to ‘entertain’ their captors during the long months awaiting embarkation would be chained to the cannonball at the ankle or forced to hold it aloft in the blistering heat for hours at a time – a tantalising hint of the defiant mindset of those recently captured women. Inside the death cell, where mutinous soldiers and rebellious captives alike were left to rot, the atmosphere remains oppressive. Its door, marked with a skull and crossbones, acts like the lid of a coffin, blocking out light and air. Yet even this tomb-like cell speaks of dissent and rebellion – why else would it have existed?

A narrow, well-worn staircase leads us from the courtyard to the officers’ quarters above. The windows offer a panoramic view of the Atlantic Ocean, evoking a distant memory of slave ships of every nation anchored offshore, plying their ignominious trade. The governor’s breezy rooms contrast starkly with the suffocating gloom of the slave holes below, where the claw marks of the desperate and the dying are still visible above a dark, indelible tidemark of human waste. The horrors endured by hundreds of tightly packed captives receive graphic illustration when our guide points to the former site of huge ‘necessary tubs’ that would have been filled to the brim with excrement. A vile death by drowning awaited those unfortunate souls who, too exhausted to perch on the edge, slipped and fell in.

We stoop low to enter the cramped corridor that led countless men, women and children to step, bound and shackled, through the ‘door of no return’. The architecture tells its own story – a narrow, single-file opening, designed to frustrate all thoughts of escape as the captives were bundled into longboats that would ferry them to the waiting ships. Yet thoughts of escape there must have been, for a whole industry was developed to equip the traders with the heavy iron chains and shackles they needed in order to prevent it.

Back in the courtyard, we are almost blinded by the brilliant sunshine reflecting from a brass plaque in honour of the millions who perished. It reads: ‘In Everlasting Memory of the anguish of our ancestors. May those who died rest in peace. May those who return find their roots. May humanity never again perpetrate such injustice against humanity. We, the living, vow to uphold this’.

Fine words indeed.

Conditions such as those in Elmina would become commonplace as local chieftains became more and more complicit in the capture and sale of their own people. During the seventeenth century, their efforts to consolidate local or regional power came to depend increasingly on the exchange of prisoners of war and other hapless victims, both male and female, in return for guns and sought-after European commodities. The result was a highly lucrative partnership – one that has survived to this day in the corrupt dealings between the power brokers of Africa and Europe.

As people-trade entrenched itself along the West African coast as far south as the Congo and Angola, those intrepid Portuguese, Danish, Dutch, French and English traders, many of whom built their own forts and trading posts, could rely on a steady supply of captives from the interior to fill the waiting barracoons – the end result of a complex process of barter and exchange of ‘equivalent’ goods in return for captured humans. Increasingly, African lives came to be valued in beads, cloth, gunpowder, rum and iron bars.

Not all chiefs took so readily to the sale of their own people. Particularly in the early years of the trade, when the slavers’ success relied heavily on the patronage of local rulers, some chiefs bucked the trend and resisted all involvement. Africa, like Europe, was no more than a vague geographical concept at the time. In reality, Europe’s slave traders encountered a complex array of kingdoms and tribes, some more sophisticated than others, with competing interests, language barriers, social and cultural differences, rivalries and territorial ambitions, as well as widely differing attitudes to slavery. Inevitably they met with powerful Africans who wanted a piece of the action. But they also found others who were vehemently opposed the trade, including some impressive African women.

As early as 1701, the Royal African Company was writing to its factors at Cape Coast castle to alert them to the dangers of local resistance, led by a woman who clearly wielded considerable power in her own right:

We are informed of a Negro Woman that has some influence in the country, and employs it always against our Influence, one Taggeba; this you must inspect and prevent in the best Methods you can and least Expense.1

Taggeba was one of several powerful African women who resisted European encroachment in the early seventeenth century. Ana Nzinga, queen of the Ndongo (c. 1581–1663) was an equally formidable opponent, a fearsome woman who remained a flea in the ear of the Portuguese throughout her thirty-year reign. As well as keeping a harem of both male and female consorts, she is said to have dressed in men’s clothing and insisted on being called ‘king’ rather than ‘queen’.

Her brazen, imperious character is legendary. During her first encounter with colonial governor Correia de Sousa, she is said to have refused his offer of a seat on the floor, ordering one of her servants to get down on his hands and knees instead to form a chair. Later, under the pretence of forming an alliance with them, she allowed herself to be baptised Dona Ana de Souza and learnt the Portuguese language. Distrusted by the Portuguese for her habit of harbouring escapees and much feared for her military prowess when resisting European intrusion, she point-blank refused to become their puppet and was never effectively subdued.2

Even though resistance to European traders was sporadic and mercilessly repressed, it persisted in some form or another for centuries. Their names may have been lost to us, yet women are known to have played a significant role militarily, spiritually and politically. Several historical accounts confirm the influence of African women as leaders and warriors: Amina or Aminata (d. 1610), the warrior Hausa queen of Zazzau (modern-day Zaria), led an army of over 20,000 in her wars of expansion and surrounded her city with defensive walls that are known to this day as ganuwar amina or ‘Amina’s walls’. Described in Hausa praise songs as ‘a woman as capable as a man’, she reigned for over thirty-five years.3

There was also Beatriz Kimpa Vita (1684–1706) of the Congo, who insisted that Jesus was an African and whose call to Congolese unity was taken as a direct challenge to the designs of European slavers and missionaries. Burnt at the stake as a heretic together with her infant son, her spiritual influence spread so far and wide that enslaved Haitians used the words from one of her prayers as a rallying cry when they rose in rebellion almost a century later.4

Over 200 years after Ana Nzinga’s rule, warrior queen Yaa Asantewaa came to embody this spirit of female resistance when, as the chosen leader of the Ashanti in their struggle against British colonialism, she denounced her fellow chiefs for allowing their king, the Asantehene, to be seized and exiled. In her words:

Now I have seen that some of you fear to go forward to fight for our king. If it were the brave days of Osei Tutu, Okomfo Anokye and Opuku Ware I, chiefs would not sit down to see their king taken without firing a shot. No white man could have dared to speak to the Chief of Asante in the way the governor spoke to you chiefs this morning. Is it true that the bravery of Asante is no more? I cannot believe it, it cannot be! I must say this: if you, the men of Asante, will not go forward, then we will. I shall call upon my fellow women. We will fight the white men. We will fight till the last of us falls on the battlefield.5

Yaa Asantewaa, born in 1840, would have been around sixty when she was elected to lead an army of 5,000 in the Ashanti war of resistance against the British at the turn of the twentieth century. Described by the British as ‘the soul and head of the whole rebellion’, she is thought to have been the mother or aunt of a chief who had been sent into exile with the king. Although she was eventually defeated and exiled herself, she remains a Ghanaian national she-ro and a figure of inspiration to this day for her refusal to bow down to colonial rule.

This is not to suggest that recalcitrant men didn’t play an equally important role in resisting the theft of their people. In 1720, Tomba, chief of the Baga, attempted to organise an alliance of popular resistance that would drive the traders and their agents into the sea. The Oba (kings) of Benin are also reputed to have been opposed to the trade for many years.6 King Agaja II of Dahomey, whose reign lasted from 1718 to 1740, is said to have been so incensed by the incursion of traders into his kingdom that he raised an army of intrepid women to help resist them. A letter, thought to have been dictated and sent by Agaja to the English king, George II, in 1731, even went so far as to propose an alternative scheme of trade, substituting the export of human beings with exports of home-grown sugar, cotton and indigo.7

On second thought, King Agaja may not be the best example of male agency. His palace was ‘a virtual city of women, experienced in the mechanics of government’ – close to 8,000 women, whose roles included blocking or promoting outsiders’ interests. Said to have exercised choice, influence and autonomy, they wielded considerable authority and power. This ferocious army of Amazonian ‘soldieresses’ was legendary both for the warriors’ physical prowess and their elevated status. They called themselves N’nonmiton (‘our mothers’) and others saw them as elite, aloof and untouchable.

As bodyguards to the king, they were trained to display speed, courage and physical endurance on the battlefield, and expected to fight to the death to protect him. Their fearsome, ruthless legacy is remembered to this day.8

There were other kings who resisted, too. According to Carl Bernard Wadstrom, who made a voyage to the coast of Guinea in 1787, the King of Almammy was so opposed to the trade that he enacted a law forbidding the transport of slaves through his territory. Wadstrom was an eyewitness when the king returned gifts sent by the Senegal Company in an attempt to win him over, declaring that ‘all the riches of that company would not divert him from his design’. Even toward the end of the eighteenth century, by which time the trade was well entrenched, the inhabitants of the Grain Coast were known both for their reluctance to trade in slaves and their habit of attacking European slavers who attempted it.

Sadly, back in Europe, such protests fell on deaf ears. After all, why concern themselves with the plight of Africans when there were such huge profits to be made? Aside from copious supplies of rum and gin, which created their own dependency, one of the most lucrative exports to Africa at the time was guns. Between August 1713 and May 1715, the Royal African Company ordered no less than 11,986 fusees, pistols, muskets and Jamaica guns for export to the Guinea coast,9 the latter made specifically for the slave trade and known for their habit of exploding the first time they were fired.10 King Tegbesu of Dahomey (King Agaja’s successor) is said to have complained bitterly that a consignment of English guns had exploded when used, injuring many of his soldiers. In 1765, a fairly typical year, 150,000 guns were exported to Africa from Birmingham alone – the beginnings of an ignominious arms trade that has killed or maimed millions of Africans and has continued unchecked into the twenty-first century.

Before long, power and guns would become inextricably linked, with the price of a slave costing anything from one to five guns, depending on the location of the sale. Soon captive Africans, typically prisoners of war, had replaced gold, ivory, pepper and redwood as the primary currency. Meanwhile, resident European factors, whose ‘palavers’ with less scrupulous local rulers left them well placed to stir up local rivalries, were often charged with deliberately fomenting unrest in a cynical move to increase demand for guns and the resulting supply of captives.

The truth is although it was Europeans who organised the triangular trade in their scramble for profit and influence, they could not have done so without co-opting some extremely power-hungry Africans. The collusion of chiefs and indigenous traders was the inevitable by-product of a system that thrived on avarice. Elmina, like hundreds of other forts and trading posts along the West African coast, would soon become a busy commercial hub, its predominantly European occupants dependent on local communities for water, fresh food, transport and, in some cases, even armed protection.

Bogus treaties with local chiefs may have given Europe’s traders an initial foot in the door, but their success – and, on some occasions, their very survival – came to rely on the services of local people: boatmen, domestic servants, messengers, traders, brokers, interpreters and so-called ‘wenches’. For them and their descendants, this trade in fellow humans would ultimately become a way of life. Treacherous currents and diseases that could devastate an entire crew encouraged European ships to anchor far offshore for their own safety. The trade would have died an early death but for the expertise of local boatmen, who were handsomely rewarded for ferrying people and goods to and from the waiting ships. If they were fortunate enough to escape capture themselves, it was only because their skills in handling the canoes, sometimes as long as eighty feet and able to carry over 100 people, were vital to the endless traffic between ship and shore.

Within 200 years, what began as a Portuguese monopoly in 1490 had become a free-for-all. As the British, French, Danish, Dutch, Prussians, Spanish and Swedish jostled with the Portuguese for strategic dominance of the coastal forts and supply routes, competition was fierce, often deadly. Elmina Castle, seized by the Dutch in 1642, changed hands several times until finally, over two centuries later, it fell under British control. A similar fate befell Cape Coast Castle, Anomabu and many other forts and trading posts, 100 of which had been built on the Gold Coast alone. Meanwhile, in the Americas, the establishment of plantations for growing sugar, tobacco, cotton, rice, coffee and other produce led to a declining interest in Africa’s gold reserves and an ever-growing demand for ‘black ivory’. This steady drain of men and women, paupers and princesses alike, would deplete the continent’s most precious resource for centuries to come. Africa is, as we know, still in recovery.

To begin with, back in Europe, the traffic in human lives provoked few moral qualms. Initially characterised by mutual curiosity and respect, relationships between Africans and Europeans only began to change once the trade became established. Slavery was a lot easier to defend if its victims could be vilified, and the justifications, however crude, were easily swallowed by Europe’s illiterate masses. Africans, it was argued, were ‘slaves by nature’, little more than apes or talking parrots, a savage, godless race whose ‘impudent nakedness’ was proof of their inherent immorality. To enslave them, therefore, was seen as an act of salvation, for it saved them from themselves. By the end of the eighteenth century, an entire racist mythology had been devised to justify African enslavement, couched in lofty, pseudo-scientific language and sanctioned by both church and state.

The extent to which Africans were dehumanised is apparent from the earliest Portuguese references to the shipment of slaves by the tonne and records of their transportation across the Atlantic like so many heads of cattle. It can be no coincidence that in Portuguese, ‘to explore’ and ‘to exploit’ are one and the same word (explorar). The Royal African Company was quick to follow suit. Bankrolled by wealthy patrons, it supplied nearly 50,000 slaves to the British West Indies between 1680 and 1688 alone.11 It would be another 120 years before Britain publicly condemned the tyranny of the transatlantic trade and the ‘great enormities … practised in Africa and upon the persons of its inhabitants, by the subjects of different European Powers’.12

The enormities were great indeed, regardless of gender. African women are prominent in the accounts of contemporary eyewitnesses and in their detailed, hand-drawn sketches of the coffle line. Secured by wooden yokes fashioned from forked tree branches that could weigh as much as seven kilos, they can be seen leading children by the hand and carrying goods or supplies. Francis Moore, factor to the Royal African Company between 1730 and 1735, recorded seeing caravans of up to 2,000 slaves tied by the neck with leather thongs in batches of thirty or forty, ‘having generally a Bundle of Corn, or an Elephant’s Tooth upon each of their heads’.13

For those seized inland, the trek from the forested interior could mean walking several hundred miles in the pitiless heat. How many Africans perished before reaching the coast can never be quantified but it is thought that close to half of them – as many as 12 million people – may have perished before they even reached the coast, either from escape attempts, wounds sustained during capture, summary execution or sheer exhaustion. In such desperate circumstances, suicide was probably one of the few available acts of resistance. Many a captive is said to have chosen death by their own hand over the trauma of being driven like cattle toward an uncertain fate.

Flogging was common practice on the coffle line, with no exception made for young children or pregnant women. Babies, the elderly or the infirm, viewed as an unnecessary encumbrance, were often abandoned en route or casually murdered. In fact, the Royal African Company tacitly encouraged such practices. In an early missive to the King of Whydah in 1701, it insisted that the company was not interested in anyone ‘above 30 years of age nor lower than four and a half feet high … nor none Sickly deformed or defective in Body or Limb … And ye Diseased and ye Aged’. A year later, a letter to their newly appointed agent, Dalby Thomas, included written instructions to procure ‘as many Boys and Girls as possible’, ideally in their early teens, and to avoid sending ‘old Negroes’.14

Rumours of these atrocities must have spread like wildfire. Deep in the interior, talking drums, which could convey news over hundreds of miles in the space of a few hours, and the tales of itinerant traders ensured that the slavers’ terrifying reputation preceded them. Explorer Vernon Cameron, who witnessed a passing slave caravan while travelling in central Africa in the mid-nineteenth century, described how, at its approach, the local people ‘immediately bolted into the village and closed the entrances’. Camped close to the path, he watched as ‘the whole caravan passed on in front, the mournful procession lasting more than two hours. Women and children, foot-sore and overburdened, were urged on unremittingly by their barbarous masters; and even when they reached their camp it was no haven of rest for the poor creatures. They were compelled to fetch water, cook, build huts and collect firewood for those who owned them’.15 Whether these captives were headed for Portuguese traders off the coast of Angola or the Arab slave markets to the north is not known, since both continued to operate long after the Atlantic trade was outlawed by the British. Either way, on the arduous journey still ahead of them, women were clearly expected to bear the brunt of the hardship.16

Mungo Park, who accompanied a slave coffle in Senegal toward the end of the eighteenth century, witnessed the miseries of the Atlantic-bound coffle first-hand, including the substitution of an enslaved man who was too sick to travel with a young village girl encountered en route. His description of her anguish on learning her fate suggests that however ignorant of their eventual destination, the captives were only too aware of the horrors that lay ahead:

Never was a face of serenity more suddenly changed into one of the deepest distress. The terror which she manifested on having the load put upon her head and the rope fastened around her neck, and the sorrow with which she bade adieu to her companions were truly affecting.17

As demand for slaves increased, the King of Whydah and other local chiefs tried securing supplies to order, mostly by means of armed raids. Not all captives were prisoners of war, however. People could be sold into slavery for a variety of reasons: debt, witchcraft, theft, adultery, non-payment of a tribute, incurring their chief’s displeasure or simply having no means to support themselves. Others, like Olaudah Equiano and his ‘dear sister’ were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time and found themselves kidnapped.

Women and girls were especially vulnerable, it seems. The female relatives of male felons, mothers who gave birth to twins, family servants, even young girls who menstruated earlier than normal risked being despatched into slavery to meet the ever-growing demand. In 1694, Captain Thomas Phillips reported that, when slaves were in short supply, the king would ‘often … sell 300 or 400 of his wives to complete their number’. On the Ivory Coast, perhaps in the hope of taking the pressure off themselves, the Avikam people stole or purchased large numbers of female slaves with a view to breeding and selling the children to the Europeans. Whatever their motives, the incentives for African suppliers must have been significant. And since guns, which represented both power and security, could only be acquired in exchange for captives, they were caught in a double bind.

Inevitably some ships’ captains, especially ‘ten percenters’ who were backed by private investors, chose to bypass the company. During periods of shortfall, when ships languished off the coast, unable to leave, kidnapping became an increasingly popular course of action. Crew members, usually confined to their quarters in a futile effort to contain the spread of disease, would then be expected to play a more active role. The sailors, many of them press-ganged into service themselves, would have been skilled in the art of people-theft. When abolitionist Thomas Clarkson interviewed twenty-two men about their involvement in the Guinea trade, one of his witnesses admitted that ‘the Europeans who frequent the coast of Africa do not hesitate to steal the natives whenever an opportunity is offered them’. His witness goes on to describe how ‘a very considerable number of the natives of Africa annually become slaves, either by being way-laid and stolen, or decoyed from home under false pretences, and then seized and sold’.18

With a local guide and sufficient armed men, the business of procuring slaves could easily bypass the middlemen. Ironically, ordinary Africans had no choice but to take steps to avoid capture by carrying weapons themselves. Others formed defensive alliances with nearby villages or relocated away from those areas most vulnerable to attack. Faced with the constant threat of raids, some villagers developed their own alarm systems. One of Clarkson’s informants had been present when several ships’ captains ‘determined to make a descent on a village at night for the purpose of getting slaves … (and) take all they could lay their hands on’. Their attempt was thwarted by a woman who, on seeing them enter her hut, ‘shrieked aloud and made a terrible crying’.

Thanks to this woman’s warning, the villagers regrouped and fought back until the raiding party, several of whom were killed or wounded in the skirmish, ‘fled without precipitation into the water’. But they did not leave empty-handed. While making their escape, five women were seized and taken back to the ship for transportation. The captured women appear to have survived the journey, for they were ‘carried to the West Indies, and the port being just opened at South Carolina, they were sold there’.19

Women and girls were probably seen as easy targets. Another of Clarkson’s informants had been present when ‘two black traders informed the Captain … that they would procure him two women slaves, if he would assist them in doing it. The Captain accordingly sent Mr — with them to a distance … of some miles from the ship. The two young women were … brought down, but under the pretence of seeing a relation at Suggery Bay to the windward of Cape Mount. When they had been enticed under this pretence to the water’s edge, they were ordered to be swum off on board the (ship’s) boat in a very heavy surf, each of the women between two men. When they were put on board the ship they were treacherously sold for slaves.’20

Few accounts have survived by those on the receiving end of such trickery, and none of them by women. Abu-Bakr al-Siddiq, born in 1790 in Timbuktu, was one of a literate minority who could record the details of his capture in writing, so he speaks for the silenced, both male and female alike. His captors, he said,

tore off my clothes, bound me with ropes, gave me a heavy load to carry. They sold me to the Christians and I was bought by a certain captain of a ship at that time. He sent me to a boat, and delivered me over to one of his sailors. The boat immediately pushed off and I was carried on board of the ship. We continued on board ship, at sea, for three months and then came on shore in the land of Jamaica. This was the beginning of my slavery until this day. I tasted the bitterness of slavery from them, and its oppressiveness!21

Captives who were not taken directly on board could be confined in the coastal forts or ‘barracoons’ for months at a time. Elmina bears witness to the many thousands who languished in filthy, overcrowded holding cells or slave pens until loaded onto ships that, if they survived the journey, would transport them to the Americas. The dehumanising process began long before embarkation. Yet despite the terrifying consequences, there is evidence that women played an active part in barracoon insurrections during the long months spent awaiting embarkation. Women were almost certainly among those who attempted a rebellion on Bence Island, ‘armed only with [their] irons and chains’.22 They also resisted in other ways, as the solitary cannonball in Elmina Castle bears witness.

Keeping in mind the evocative images of the coffle line and the barracoons, it’s worth remembering that by no means all African women who encountered European men did so in shackles. In the coastal fortresses and trading posts, despite phenomenally high mortality rates, some Europeans survived disease, foreign bombardment, political intrigue or the effects of excessive alcohol consumption long enough to form intimate relationships with local women. In fact, the promise of copious sex, typically with young girls, was probably one of the attractions used to lure them overseas. At Cape Coast Castle, just up the coast from Elmina, it was common practice to supply newly arrived officers with an African ‘wench’ to serve as cook, maid and bed warmer.23 Similarly, in settlements around the estuary of the River Sierra Leone, it was said that ‘every man hath his whore’.24

Polygamous arrangements were commonplace, mimicking local practices. During a visit in 1694, Thomas Phillips, a ship’s captain, described the European habit of taking African mistresses as ‘a pleasant way of marrying, for they can turn them on and off and take others at pleasure’. This, he observed somewhat smugly, ‘makes (the women) very careful to humour their husbands, in washing their linen, cleaning their chambers &c, &c. and the charge of keeping them is little or nothing’.25 Some of these women may have been willing victims. Others – like the ‘Shanti beautee’, purchased for around £21 in equivalent goods when her male owner, the governor, died; or ‘DM’s lady’, who was ‘sent off the coast’ in similar circumstances – found that their favoured status offered them no guarantee of any long-term security.

Relationships with local women were typically casual or short-lived, though some clearly weren’t. Officers’ wills, letters and other surviving records suggest that marriages at Cape Coast Castle, while not recognised in British law, conformed largely to local customs by requiring payment of a dowry to the girl’s mother and a monthly allowance. This practice was not confined to the British. In his letters home, Paul Erdmann Isert, chief surgeon to the Danish in Christiansborg, Accra, from 1783 to 1786, declared that ‘one of the most peculiar customs here is the marriage of the Europeans to the daughters of the country’. He went on to describe how ‘a Black woman is paid one thaler monthly and a Mulatto woman two thaler monthly by their husbands, and … given clothing twice a year’. Not only was this payment for services rendered viewed as an entitlement, but when a woman found herself wedded to a ‘ne’er-do-well’, she had the right to complain. By way of recompense, her allowance would either be deducted at source from the man’s wages or his wages paid over to the woman in their entirety, for her to manage on his behalf.26

Isert also described how ‘the new husband can send his wife packing the next day if he feels like it’, implying that some European men were happy to exploit these arrangements to suit their own sexual appetite. Even so, it is clear that some of these relationships endured. At Cape Coast, Officer Miles arranged for monthly payments be made to his ‘Mulattoe Girl’ Jamah for over three years, possibly longer, from May 1776, suggesting more than a casual fling. Similarly, on his death in May 1795, Thomas Mitchell left his woman, Nance, the princely sum of twenty pounds, to be paid in gold dust, plus two gold rings ‘in consideration of her strict attention and attendance on me during the three years we have lived together’.

Occasionally – perhaps more often than was admitted – such unions led to genuine mutual affection. James Phipps, who was a governor of the castle early in the eighteenth century, is said to have implored his ‘mulatto’ wife, who bore him several children, to return with him to England. She refused the offer but allowed him to take their four children there to be educated. Another governor, Irishman Richard Brew, fathered seven children with the same woman before returning home in the 1790s.27 His contemporary, Dutchman Jan Neizer, having married a local woman called Aba, was apparently so content with his lot that he built her a grand house and named it ‘Harmonie’.

For some powerful local women, many of whom were slave owners or traders in their own right, political or commercial interests were probably a more pressing consideration than love and affection. The Queen of Winneba, who took the Royal African Company’s chief factor, Nicholas Buckeridge, as her lover, probably had more pragmatic motives. Further north, the formidable Senhora Doll, a member of the influential Ya Kumba family, was no doubt securing her interests, too, when she agreed to marry Thomas Corker of Falmouth, the company’s last factor. Known as ‘the Duchess of Sherbro’ by the European slave captains she entertained, she and her descendants went on to establish a small standing army of free Africans, maintaining control over a strategic stretch of land along the banks of the river Sherbro.28

Casting all African women as victims obscures the fact that relationships with European men, however short-lived or precarious, offered their concubines a degree of financial security that their wives back in Europe would have envied. Moreover, some women made a lucrative living from the trade. In the Bissagos Islands off Cape Verde, where an earlier preference for male captives had created a large female majority, women controlled most of the transactions. The children resulting from their liaisons with European men populated numerous offshore islands and coastal towns. Rarely acknowledged by the fathers, their Euro-African offspring would eventually become a trading force in their own right, known as caboceers. By straddling the cultural and linguistic divide between Europeans and Africans, both sons and daughters acquired increasing power and status, the latter often mentioned in surviving documents as wives, mistresses or favoured ‘wenches’.

One such woman was Betsy Heard, the daughter of a liaison between a Liverpool trader and a local woman. Schooled in England, she returned home to inherit her father’s trading assets and subsequently rose to prominence as a dealer in slaves along the banks of the River Bereira. By 1794, she had established a monopoly on trade in the area. As owner of the main wharf in Bereira, including a warehouse and several trading ships, she wielded sufficient influence to act as mediator in a long-standing dispute between the Sierra Leone Company and local chiefs, who are said to have regarded her as a queen.29

The patronage of chiefs and the mediation of caboceers would become vital to Europe’s traders, as the theft of Africa’s people became entrenched. Procuring and enslaving captive Africans could be a slow and laborious business, especially when competing with faster or better-stocked ships. Once the local market became flooded with cheap European goods, the cost of ‘black ivory’ increased and the supply of captured Africans began to dwindle. In 1764, Captain Miller of the Black Prince complained that he’d waited six months for his agent to acquire just twenty slaves. And when the Pearl, which sailed out of Bristol in 1790, had to wait over nine months in Old Calabar for a viable cargo, both the crew and their captives suffered high mortality rates before they could set sail.30 Many a captive perished in the disease-ridden holds of ships as they languished off the coast, waiting for the quota to be filled. Others endured the prolonged torture of captivity for months, forced to lie spoon-like in their own excrement, vomit or menstrual blood until the ships were fully loaded.

Selection for sale involved detailed and intimate inspection, with specially appointed ships’ ‘surgeons’ examining ‘every part of every one of them, to the smallest member, men and women being stark naked’.31 Captain Phillips recorded an account of one such transaction in his diary. ‘Our surgeon’, he wrote, ‘is forced to examine the privities of both men and women with the nicest scrutiny’.32 It was also common practice for captives to be branded on the shoulder or breast with a hot iron, to ensure that they could be readily identified by their purchasers. Their suppurating wounds would have been magnets for infection.

Cruelties like this went with the territory. Traders were not averse to beating or murdering those captives who, on account of ‘being … defective in their limbs, eyes or teeth; or grown grey, or … [victims of] the venereal disease, or any other imperfection’ were rejected by ships’ captains and other European buyers. It is doubtful that any concessions were made to women. These paragons of European civilisation simply turned away when ‘traders frequently beat those Negroes which are objected to by the captains and use them with great severity … Instances have happened … that the traders have dropped their canoes under the stern of the vessel and instantly beheaded them in sight of the captain’.33

Of course, brutality is not confined to any one race. It never has been. Both Africans and Europeans were guilty of such atrocities, reflecting contemporary attitudes toward violence on both continents. It is tempting to romanticise Africa by forgetting that slavery and human sacrifice preceded European encroachment or presenting the few chiefs who resisted as paragons of altruism. However, this would be a misrepresentation.

Having said that, it was the Europeans who initiated and oversaw these transactions, and it was they who established the parameters of what was acceptable. The men involved showed such callous disregard for human life that ex-slave Olaudah Equiano, turning the popular stereotype of African barbarism on its head, remarked: ‘I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me … the white people looked and acted, as I thought, in so savage a manner; for I had never seen among any people such instances of brutal cruelty.’34

Negroes in the Bilge, 1835 engraving of painting by German artist Johann Moritz Rugendas (Alamy)