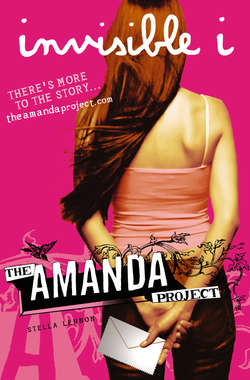

Читать книгу Invisible i - Stella Lennon - Страница 12

CHAPTER 8

ОглавлениеNia snickered when Mr. Thornhill offered us a chance to “come clean” right after we’d each picked up a bucket filled with rags, rolls of paper towels, and cleaning products piled by the door. It took me a minute to get the joke about cleaning, but I’m not sure if that was because Nia’s smarter than I am or if it’s because I was so confused by all the thoughts whirling through my head that I didn’t have room in my brain for a pun.

When nobody said anything, he just gestured toward the door and we trooped out in a line: Hal first, then Nia, then me.

“It’s not like we’re going to be able to get the stuff off his car with this,” I pointed out, rattling the bucket toward their backs. “Spray paint doesn’t exactly wash off.”

Neither of them said anything, as if during lunch they’d made a pact to ignore me. Well, two could play at that game, and I didn’t say anything more. A crowd was gathered by the gate to the faculty parking lot to gape at Mr. Thornhill’s car (some people had out their phones and were taking pictures); at first the security guard, who was holding them back, wouldn’t let us through. Hal had to explain for about fifty years that we had to go to the car, and even then the guy was reluctant to let us pass. As we walked past him, I spotted Lee’s curly dark hair towering above the crowd and then I saw Traci, Heidi, and Jake, who were all standing with him. Lee saw me before they did, maybe because he’s so tall, and he put his fists up over his head and shouted, “Go, Callie!” as Traci and Heidi clapped and Jake whistled. I hoped Hal and Nia heard them. I hoped they realized who they were ignoring.

The VP’s ancient Honda Civic was parked far enough away from the crowd that the noise of the onlookers was muffled, or maybe it was just that the sensory overload of looking at something so vivid made it difficult to register anything else. The clouds had rolled in since we’d first looked out Thornhill’s office window, but even in the watery sunlight of a March afternoon, the car pulsed with color and energy.

“Wow,” said Hal.

I had to agree. From a distance, we’d only been able to see the biggest shapes, but up close you could make out the detail work—tiny birds carrying intricate olive branches, long daisy chains intertwining with meticulously drawn rainbows. It wasn’t just bright and colorful, it was really, really good art.

Suddenly, I thought of something. Despite my private vow not to talk to either Hal or Nia, I turned to Hal, who was standing next to me admiring the lunar landscape that covered the driver’s side of the windshield. “Did you draw this?”

Either Hal was seriously ignoring me or he hadn’t heard what I said. He reached out with his index finger and traced the edge of the moon. “Hey, it’s—” he started to say, but before he could finish, I grabbed his arm.

“Did you do this?”

“What?” He turned to face me but I could tell he was still absorbed in admiring the masterpiece that was Thornhill’s car. I noticed that after he’d touched the moon, his finger had a light coating of bluish-white.

“I said, did you draw this?” Hal was the best artist at Endeavor, and there was no doubt someone with real talent had decorated this car.

“I wish,” he said. He turned back to admire the car. “Maybe I could have done this, but only with her, you know?” I wasn’t sure what he meant, but I couldn’t deny that Hal’s tone was friendly enough. I wondered if I’d been paranoid to think he and Nia were ignoring me.

“How did you even know her?” I hadn’t meant to sound so accusatory, but my question came out like an attack.

Hal didn’t say anything, but Nia did. “Oh, what, now you’re the holder of the social registry for the entire grade?”

None of the other I-Girls would have tolerated Nia’s being so rude, but the three of them are way better at confrontations than I am. For a second I tried to think up a snappy comeback,

but when nothing came to me, I just ended up with, “I didn’t realize you guys were friends, that’s all.” Then I shrugged, like there hadn’t been any judgment in my assumption.

I’d expected Nia to back off, but instead she kept going. “Oh, right,” she said. “You and your friends just—”

“Look!” said Hal. He’d been circling the car, and now he was pointing at the trunk.

Glad to have an excuse not to fight with Nia without having to feel like a wimp, I went over to where he was standing and followed his finger. Scattered across the trunk were half a dozen bears, birds, and cats that were the same as the ones on our lockers. There was another animal, too—a lizard of some sort. Then there were stars and moons and a bunch of peace signs.

“That’s a lizard,” I said, half to myself and half out loud. “And that’s a cat—”

“It’s a cougar,” said Hal, rubbing his wrist unconsciously for a second.

I hadn’t noticed that Nia had come up behind me until she spat out, “You thought it was a cat? It doesn’t look anything like a cat.”

This time my comeback was out of my mouth before I even realized I’d formulated it. “Gee, I didn’t realize you were such a friggin' nature girl, Nia,” I snapped. “When you’re on the Discovery Channel talking about the indigenous wildlife of Orion, I’ll be sure to watch.”

“Like I’d even care."

“Um, could you two—” said Hal quietly.

But Nia was on a roll. “And where do you come off questioning our friendships with Amanda anyway? What about yours? I mean, I never saw her hanging out with you and your stupid I-Girls. You probably tried to get her to be friends with you, only she wouldn’t let you call her Mandi so you dropped the whole idea!”

I could feel my face getting red, and I was so mad I forgot I was still holding the bucket as I reached out my arm to point at her. “Nia, you’re so jealous it’s pathetic. Like Amanda would ever, ever in a million years have hung out with someone as—” The bucket swung wildly in my hand, and one of the bottles of cleaner fell to the pavement.

“Hey!” Hal’s voice was a shout this time. I’d never heard him yell before, and it shut me up.

“Listen,” he continued in his normal voice. “I don’t pretend to understand Amanda or what motivated her or anything. But one thing I do know is that she didn’t do anything randomly. And I have a really strong feeling right now. This"—he pointed at the car and looked from me to Nia—"is a message.”

I’m basically the least superstitious person in the world, but as soon as Hal said that, I shivered. Was it possible? Was Amanda trying to tell us something?

Hal continued. “Now, here’s what I can tell you about what she’s drawn. My totem is the cougar. Strong but solitary.” I felt myself blush again when he described himself that way, but he didn’t seem at all embarrassed.

Hal’s words had some kind of magical softening effect on Nia, who pointed at the bird. “That’s me,” she breathed, her voice quiet and almost dreamy. “Night owl. Wise. Independent.”

I managed not to laugh when she said “independent.” Was that what we were now calling people who were incapable of functioning in a social setting?

Hal jostled me gently in the shoulder, and I realized it was my turn. “Bears are strong,” I said slowly. I didn’t add the other important bear fact Amanda had reminded me of: Bears hibernate.

Nia had leaned against the car while Hal and I were talking, and when she stood up, she instinctively brushed some dust off her hip. I remembered Hal’s finger.

“It’s chalk,” I almost shouted.

Hal smacked his forehead. “Yes! That’s what I was going to tell you before. It’s not paint at all.”

“What?” Nia looked from me to Hal.

“The drawing. It’s chalk. Look.” I touched my finger to a bright red apple and dragged it against the metal surface of the car. When I pulled my hand away, there was a red streak along my skin.

Hal leaned down until his face was less than an inch from the car’s surface. “You know, now that I’m looking more closely, I think it’s chalk and pastels,” he said. “This should come off the car really easily.”

“I hate the idea of erasing it,” said Nia.

I knew exactly what she meant. Even if this wasn’t some kind of message from Amanda, it was from her. And it was so cool. I couldn’t wait to ask Amanda about it.

Wishing I could talk to Amanda made me think of something.

“Hey, have you guys heard from her? I tried texting her and calling, but she didn’t answer.”

Both Hal and Nia shook their heads. “Nothing,” said Nia, and the way she said it made me know they’d spent the day calling her, too.

“I’m going to take pictures.” Hal took out his phone even as he said it. “Will you guys help me?”

Neither of us answered him, we just grabbed our phones and began circling the car with them.

“Look!” Nia was sitting on the pavement by the driver’s side door, pointing at the very edge of the car’s side panel, just behind the tire.

Unlike the cougar, this animal was immediately recognizable to me. “The coyote,” said Hal. “Amanda’s totem,” announced Nia.

“Me? I’m the coyote. The trickster.” She made a fist with her hand, then opened it and showed me her empty palm. “Now you see me, now you don’t.”

Supposedly I was catching Amanda up on quadratic equations, but really she was teaching me about totems, specifically hers and mine. When I pointed out that totems and superstition and ancient belief systems were about as far from trigonometry as you could get, Amanda gestured at me with her quill pen.

“Au contraire,” she said. “Belief systems are belief systems.”

“Oh, come on!” I said. “Math isn’t a belief system, it’s an explanation for how things work.”

“Right,” said Amanda. “In other words, it’s a belief system.”

She was wearing something in her hair that made it look as if she’d grown a waist-length ponytail overnight, and her dress, with its puffy sleeves and lace edging, definitely looked like it was something out of another century. I’d meant to ask her about the outfit—the hair and the pen and the dress, but as usual, I’d gotten sidetracked. That was the thing about talking to Amanda: I could never figure out how we’d gotten on the subject we were discussing or how we’d gotten off the subject I’d thought we were on.

“Wait, are you telling me you don’t believe in math?” Over the course of the past two weeks, I’d discovered that Amanda was probably the best mathematician I knew outside of my mom. She was truly a genius with numbers. How could she question their fundamental truth?

“I believe in math,” she said. “It’s not like the tooth fairy or Santa. I believe it exists. I just don’t think it explains things any better than a lot of other belief systems just because it happens to be in fashion in this particular place at this particular moment in history.”

“So, what, are you talking about, like … God?” This was definitely the weirdest conversation I’d ever had with someone. I tried to imagine talking about God with Heidi or Traci or Kelli.

“Religion is another belief system,” she said. “It happens not to be mine.”

“So, like, what’s yours?” I didn’t mean to sound defensive, but sometimes talking to Amanda made me feel like I was always one crucial step behind her.

“What’s my belief system …” She leaned her head against the wall and closed her eyes for a minute. Then, without opening them, she said, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

I shook my head. “There may be a lot of things in heaven and earth, but the point is, you can still count them.”

She opened her eyes and locked them with mine. “That’s what I’m telling you, Callie,” she said. “You can’t.”

Nia’s camera clicked, and without really looking at what I was photographing I pointed my phone in the general direction of the coyote and took a picture. None of us said anything for a minute.

“Okay,” said Hal finally. “Amanda needs us to do something for her.”

A car pulling out of the circular driveway at the front of the school honked its horn, and when I looked up, I saw Heidi’s mom’s BMW SUV pulling away. Heidi was in the passenger seat and Traci was sitting in the back. She shouted out something that sounded like, Call me! as the car turned onto Ridgeway Drive.

It was so weird that I could be having these two interactions at once: one, the most mundane and transparent, the other unique and mysterious. It was like existing in two parallel universes simultaneously.

But I couldn’t ignore the gravitational pull of what Hal had just said. Turning back to him, I said, “But what does she want from us? And why couldn’t she just ask us for it?”

“He’s not a mind reader,” said Nia. Any softness that had been in her voice earlier was definitely gone.

Okay, I’d had just about enough of this. “Do you have some kind of problem with me or something?” I asked. “I mean, how, exactly, did I manage to offend you in the past five minutes?”

“Let’s see,” said Nia, tilting her head to the side and pressing her index finger to her temple in imitation of someone thinking hard. Then she straightened her head and sneered at me. “No, I’d have to say you have managed not to do anything offensive in the past five minutes.”

“Are you two going to keep—” Hal interrupted, but this time I didn’t care what he had to say.

“Nia, I have never, never done anything to you and now you’re acting like—”

“You’ve never done anything to me?” Nia stood up and took a step toward me, lowering her voice until she was practically hissing. “You’ve never done anything to me? Oh, that’s a good one, Callie. Um, do the words Keith Harmon mean anything to you?”

I took a step back, but it wasn’t just to get away from Nia’s scary voice. The words Keith Harmon did mean something to me.

“That wasn’t me.”

“Yeah, right,” said Nia, turning her back on me.

I reached out and grabbed for her arm. “Seriously, Nia, that wasn’t me.”

She snatched her arm away from me, like there was something revolting about my touch, and I was reminded of Traci’s aborted cootie shot earlier. “Well, like my mom says, ’Lie down with dogs, get up with fleas.’”

At first I didn’t realize what she was saying, and then I did. “My friends are not dogs!"

“Maybe not on the outside,” said Nia, and she went back to snapping pictures of the car.

My heart was pounding. If I was all about avoiding confrontations, Nia was all about having them. No wonder she didn’t have any friends.

But even as I thought that, I couldn’t help cringing a little at the memory of what Heidi had done to Nia in seventh grade.

Nia and Heidi weren’t just in the same math class that year, they also had English together. One day, maybe a week after she’d turned Heidi and Traci in for cheating, Nia left her English notebook behind in class. Heidi picked it up because, as she told us at lunch, she wanted to be a good citizen, and then she dropped it; it happened to flip open, and what did it happen to open to but a page with a few notes on direct objects and predicate adjectives and a small heart in the margin with the initials NR and KH inside of it.

The truth is, I really don’t know exactly what happened or whose idea it was because my dad and I went to Washington, D.C. that weekend to meet my mom at a NASA conference she’d spent the week attending. But apparently, Heidi or Traci or Kelli or maybe all three of them created keith.harmon95@yahoo.com or some address like that, and they emailed Nia and then Nia emailed “Keith” back and then “Keith” emailed Nia and so on. By Monday morning, Heidi had a whole string of emails to show me and the rest of the seventh grade, emails in which Nia admitted she’d always thought Keith was cute and agreed to go out with him sometime. At that point, Nia was just a little geeky with her goofy braids and glasses, but she wasn’t a leper. And even then Cisco Rivera was Cisco Rivera, so maybe if she’d never pissed Heidi off, she could have survived middle school as a neutral. But no.

The whole thing was really, really bad. For a long time, Nia couldn’t walk by anyone without hearing something like, Going to meet your boyfriend, Nia? Or, Oooh, Nia, I think I just saw Keith, were you looking for him? Every time I passed Nia’s locker, I’d see something stuck on it—a piece of paper with NR and KH on it or a dead flower or, once, simply the words AS IF!!!!!! As far as I was concerned, she’d brought the whole thing on herself (what had she been thinking, that Heidi and Traci would allow her to live in peace after she turned them in?), but even I felt kind of bad for her by the end.

Part of me knew I should say something to them, but it wasn’t like I was that good of friends with Heidi and Kelli and Traci. I still felt a little as if … I don’t know, as if I were on probation or something. I mean, now if they did something like that, I would definitely tell them to stop. And anyway, they wouldn’t do anything like that anymore. People do a lot of stuff in middle school that they wouldn’t do in high school. You can’t judge someone forever based on one mistake.

Right at that moment, as if she’d been sent or something, Bea Rossiter limped out the front door. I watched her get into her mom’s waiting car and drive away.

I closed my eyes. What had happened with Bea was different.

But a little voice in my head said, Was it really?