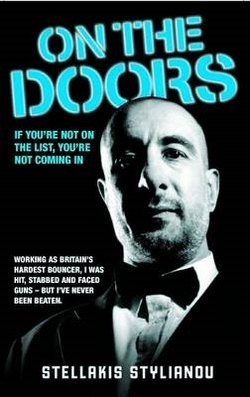

Читать книгу On the Doors - Working as Britain's Hardest Bouncer, I Was Hit, Stabbed and Faced Guns - But I've Never Been Beaten - Stellakis Stylianou - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHEN THE GOING GETS TOUGH

ОглавлениеIF YOU CHASE TWO RABBITS YOU WON’T CATCH EITHER

STILKS

T HE INCESSANT, RHYTHMIC WHIRR OF AN OLD SEWING MACHINE WAS THE SOUND OF MY CHILDHOOD.

It was always there in the background as my mum sewed together anything for the East End sweat shops that paid her a pittance and kept our whole family in a state of poverty. At times, we barely knew where the next meal was coming from and, as for luxuries like a television or toys to play with, forget it. Those sort of things were for other people, not for us.

The only time the sewing machine stopped was so my mum could cook us dinner.

My mum and dad, Helene and Andreas Stylianou, had come to Britain from Cyprus after the war, hoping to build a better future for themselves. They were grafters, Dad working in a butter factory on the production line turning out pack after pack of the stuff, while Mum was at her sewing machine all hours that God sent.

I came along on 21 July 1958. Stellakis Stylianou, after me grandad. But why don’t you just call me Stilks. Everyone else does.

I’m told I was born in London University Hospital, within one mile of Bow Bells, which makes me a cockney, but I can’t remember the very early years. For me, home was in Plumstead, South London, a little three-bedroom Victorian terraced house in Wickham Lane, where you could hear everything that went on because all we had was bare floorboards and old pieces of lino. The place would fairly echo. There was an outside toilet and a boiler in the kitchen which we stoked up with coal to get hot water. Hot water was scarce so we all had to use the same water when we had a bath, which was a tin one in the kitchen.

And the sound of that sewing machine would drone on all the time.

We might have had fuck all, but we were a close-knit family and, when my sister Yianoula was born two years after me and my baby sister Maria a couple of years later, the family seemed to be complete. The only thing was, none of us spoke English. At home with the family and with our friends, we all spoke Greek. In fact, I didn’t learn English ’til I went to Galleon’s Mount Infants School at the age of seven. And I hated it at the beginning, ’cos I didn’t know anyone and I couldn’t speak the lingo. And it was only when I was sitting at my desk, looking pained and crossing my legs, that I had the courage to stick my hand up in the air.

‘Toilet?’ said Miss, pointing her questioning finger at me.

And that was the first word I ever learned in the English language – ‘Toilet’.

After a few days I got settled into school and one of my first friends was Mark Rowe, who now promotes Julius Francis, the boxer. Even in those days, we used to pretend to be karate experts going round the playground trying to chop up pieces of wood with our bare hands. The only result of that was that I was always going home with bruised hands. But I was never questioned by my parents ’cos they were always working and we didn’t get that much time with ’em.

But the wonderful thing about my childhood is that we had these massive woods right behind the house, and that became the place to play. We’d march all around, roll over, jump up, laugh and become lost in them. It was in the woods that I found this rusty old bicycle frame. I knew what it was. I had wanted a bicycle for so long, I’d cried in front of Dad for one. That’s how desperate it got.

Anyway, with the frame well stored I went in search of the wheels. My mate Keith Waghorn got me one and I forget where the other one came from, but anyway, we got ’em. The gears and chain were a piece of piss, and I was off. I kept the bike in me den in the woods. And I got it ready for the day of me birthday – 21 July. Mum and Dad had bought me a pair of shoes! So I snuck away in the afternoon and got my bike out. I was ready to ride … And it was all going fine ’til I started to have a race with Keith going down Gravel Hill. I was doing about 30mph when I realised we hadn’t fitted any brakes. I thought, Shit. The only way to stop myself was by putting me feet on the road. And I had to do this from about three-quarters of the way down ’cos there was a crossroads at the bottom. And that was it, sparks on the tarmac, soles burning up. I stopped just before the major road junction, and fell off …

When my mum saw me shoes she went fucking ballistic. They were ruined. I’d only get a pair of shoes once a year and I had to look after them, but these were fucking ruined. Dad comes running in, spots the shoes, and then I know I’m in for a beating. My dad was a big fella, 6ft tall, 19st, he only had to hit you once and you knew it. And I’ll tell you what, I’ve taken a few beatings in my time but the one that left a real impression was the one I got from my dad when I ruined me new shoes.

I was always getting into scrapes, mainly ’cos we had to amuse ourselves all the time. We didn’t even have a fucking telly until I was eight years old and then it was one of them that kept going wonky and you had to hit it on the side.

I was a cheeky bugger and I remember one day thinking, How can I annoy Mum? My sister Maria was only four at the time. There was a ladder me dad left out at the back of the house where he had been painting the windows. So I made Maria climb to the top of this ladder and stand on the ledge, then I went and told me mum, ‘Look, Mum, Maria’s climbed up the ladder and she’s stuck on the second-floor ledge.’

Mum went mad, but she thought of the kids first all the time so she had to try and climb this ladder herself. There she was swaying about and I was pissing myself laughing. Us kids were always pulling as many tricks on each other as we could. You see, we were bored most of the time.

When I was about eight or nine, me and a couple of other kids in the gang used to go round to these greenhouses where they grew tomatoes. And we’d throw stones at the greenhouses and break the glass. We had no intention of nicking the tomatoes or anything like that. We used to like breaking the windows and listening to the glass smashing. Then I’d go round the front and I’d tell the bloke I’d seen these boys throwing stones. I’m sure the bloke could see through it, but he would give me a bit of change to make sure the kids didn’t do it any more. Remember, we didn’t have any money for sweets and stuff and that was the way I’d make a bit.

When I did get up to mischief, I think it was because I kept having to prove meself. You see, I was a really sickly child. I know if you look at me now, 16st and a threat to the unruly, then you won’t believe it. But I’m telling ya, I was a weak kid; I couldn’t have been more than 6st, I was always in and out of hospital. I suffered from acute mastoiditis or something, which affects one of the bones in your ear. So I was always having operations on my ear. Me grandmother and me dad had bad ears, so from birth I was always having earaches and I was always ill. If it weren’t me ear, it was me appendix.

I can still smell the wards and corridors of St Nicholas Hospital, Plumstead. They would echo and smell of Dettol. I can remember going in there, having me ear done, going home for a week and then going back for another operation. Mastoiditis is when the bone in the ear goes off and it seeps smelly pus out of your ear. So they have to cut away the bone; it’s a two-hour operation. If they don’t do it right, your face can drop and it can affect your brain as well. I had loads of operations but they never put it right on the National Health. It was only about eight years ago when I went and had it done privately that it was put right. Bloody National Health Service.

I’d be happy to get home from hospital. There was something reassuring about the background noise in our house.

The first weapon I ever had, if you can call it that, was a bow and arrow I made up in the woods. I was really proud of it and after I’d done all the target practice at the trees, I thought, What can I shoot now? And there was me sister. It was a pure accident but I shot her in the head. Here was this big, long stick lodged in her head and she was screaming and crying. Me mum had to take her up the hospital to have this arrow removed. So there we was again up the bloody St Nicholas.

Some nurses said, ‘Hello, Mrs Stylianou, and what’s the matter now?’

What’s the matter now – was she fucking blind? Here was a small child with an arrow sticking out of its head.

‘My sister’s got a headache,’ I said cheekily, which earned a clip round the ear from Mum. That hospital’s been closed down now and I’m not surprised; once our family stopped going, there probably wasn’t much reason to keep it open.

But I felt really bad about what I’d done to our Maria, even though Mum and Dad accepted it was an accident. And I got off lightly. But even to this day, I think it’s one of the things that put me off using weapons when I got older. I use judo holds and me fists now and I’ve never injured another fucker by accident. If they got hurt, it was because they had it coming to ’em.

But in those days, when you’re a kid, weapons are exciting and one day Dad came home with an air rifle. Dunno where he got it. Could have been from a mate at work or he could have got it out of a second-hand shop, which is where a lot of our stuff came from. Anyway, I thought, this is fucking brilliant. So I says, ‘Dad, got any targets?’

He goes, ‘Stellakis, this is not for target practice. I want you to go up in the woods and shoot pigeons so we can have something to eat! We’re gonna have pellafi.’

‘What the fuck’s pellafi, Dad?’

‘It’s a Greek rice dish with pigeons.’

We were so poor now we were having to go hunting for our food in the middle of South London. So I started practising a bit to get me eye in and within a couple of days I was over the back. When you shoot pigeons out of the nest, you have to make sure the baby pigeons have grown to a good enough, edible size, but not so big that they can fly away. Shoot the mother first, then climb up the tree and you’ve got two more. Now ya got a meal.

Me dad showed me how to pluck the feathers and with the babies you’d pull their heads off. Just hold it and twist. I didn’t like the idea at first, I thought it was cruel and that, but soon got the hang of it. I was soon eating everything – the sparrows, the blackbirds, the thrushes. Anything, as long as it wasn’t a bird that eats meat. If a bird eats meat, like a crow, you can’t eat it. But if it eats seed, you’re alright.

By the age of 12, I was skinning a rabbit quite easily; just cut it round the throat, grab the skin and pull it and it comes off in one go like a jumper.

Our food was very basic. I remember coming home one night and me mum’s at the sink and I’ve looked over and she’s got this lamb’s head. She was washing it and brushing the teeth.

‘What ya doing, Mum?’ I ask. ‘Whassat?’

She says, ‘It’s a lamb’s head.’

‘But what are you brushing its teeth for?’

‘Because we are going to eat it. You wait and see, it’s nice.’

I knew proper joints of meat were expensive. But I thought, Nah, we’re not gonna eat that, are we? So there was Mum cleaning it out; she pulls the tongue out and scrapes it, getting all the hairs and muck off it, washing it, preparing it. Then this head goes in the oven, with potatoes round it.

It comes out the oven and I can remember there was me and me two sisters, but only two eyes. So I goes, ‘Dad, I’m havin’ one of them.’

And he says, ‘All right,’ ’cos the son in Greek Cypriot families always gets the first choice of everything. So I put my finger in and pulled it out and the eye had all grown from being small in the socket to the size of a fucking golf ball. Dad said, ‘Just put it in your mouth and suck,’ and I can remember it just melted in me mouth. But there’s a hard white bit left and you just spit that out.

There’s a saying that the meat nearest the bone is the sweetest and the meat on the cheekbone of the lamb’s head was a different class, it was really nice.

Then Dad got a hammer and he hit the lamb’s head, cracking open the skull and removing the brain which he got out in one go with a spoon. He told me to eat it with salt and lemon and it would give me brains, too. Well, it never helped!

We used to eat really weird stuff. For years, I used to eat this stuff which I thought was liver until, one day, I asked someone if they had any ‘soft liver’ like me mum made. They said there was no such thing, so I asked Mum.

I said, ‘You know that soft liver you give us …’

She stopped me right there and said, ‘Son, that weren’t no soft liver, that’s the lungs.’ I mean, honestly, the fucking lungs!

But our parents were the salt of the earth. They would scrimp and save and that sound that kept haunting me, that whirring drone of the sewing machine, was the sound of a working-class family trying to keep up and do their best.

I only remember ever having two holidays when I was a kid. One was to Margate and all I can remember then was going round the amusement arcade putting old pennies in the slot machines. And the other one, the big one, was when we all went to Cyprus.

Dad had announced we were going to Cyprus months and months before it happened. And I swear to God that bloody sewing machine went into overdrive. It was do-doing and der-dering it’s little heart out right round the clock to try and get us the fares. There weren’t many luxuries in our lives but now there were to be none at all; everything was being sacrificed to get us to Cyprus.

Even from a very small child, I’d dreamed of going there because Dad went on about it so much. How it was hot and sunny and not cold and damp like South London. But if I was cheeky enough to ask why he had left in the first place, it would be another fucking clip round the ear.

So me and me sisters were counting the days ’til we could go on our holiday to Cyprus. We’d never been anywhere exciting like that and we’d certainly never ever been in an aeroplane. It was all a bit too much for us to grasp. I was about ten at the time, I suppose, and I only realised we were really going on holiday when Mum bought me a new pair of swimming trunks. They were incredible … bright red they were.

We went for two weeks and we was staying at my grandad’s house in Nicosia, and we’d travel to the nearest beaches like Larnaca for days out or up to the Trodos mountains. There was something every day. One day, I remember, we found ourselves – me and me sisters – on the beach playing around and we decided to go in the sea. But ’cos of the mastoiditis I suffered from, I wasn’t allowed to get me ear wet so just had to paddle around in the shallow bit by the beach. That was all right but it was boring, and so I started walking out a bit when all of a sudden the seabed dropped away … ’Cos I’d never been able to get me ear wet, I’d never been able to swim. I was still a paddler!

Suddenly I was bobbing around. I was going under and then twisting around and coming back up. There seemed to be a tremendous amount of water and it was dragging me away and dragging me down. They say your life flashes before you when you’re drowning, and that’s what happened to me. It hadn’t been much of a poxy life. I was only ten years old and I’d spent it in South London. But it was the only one I’d had, and it was flashing before me. The thing was, I liked the feeling. If I could have that feelin’ again I would. It’s like this big whoosh, and everything you’ve done, you see it all again in seconds. It was an incredible experience … but I knew I was in real deep shit.

I was shouting for help, but Mum and Dad weren’t on the beach, they must have gone for a cup of tea or something. There were only my two sisters. But the eldest one, Yianoula, who was only eight years old, came running into the sea. I thought, Fuck, she can’t swim very well herself! She got to me, but with me panicking at the time, I pushed her down. And now there were both of us drowning. I remember I’d swallowed a lot of water and I was right at drowning point, lashing out, shouting, pushing Yianoula under. These sounds were in my head and I swear to this day it was that bloody sound of the sewing machine. It had haunted me throughout my little life and now it was gonna haunt me as I died.

I learned later that my little sister Maria had run up the beach to try and get some help. But I didn’t know that and I couldn’t cling on any longer. The sound was running through my head as the waves were washing over me and I was slowly slipping unconscious into the depths of the sea.

The last thing I remember was thinking, Mum’s going be right fucking mad at me for drowning with me new swimming trunks on.

* * *

I wasn’t surprised when I failed the 11+ exams, because I couldn’t read or write. But I was surprised when I arrived at Bloomfield Secondary School in Plum Lane, Shooter’s Hill. There were all these other kids and they were bigger than me!

The first time I was picked on it was just shoutin’ names. They’d point at me and shout ‘Rumple-STILKS-kin’. I’d been nicknamed Stilks at junior school, because who the fuck can remember Stellakis Stylianou! But the name had followed me to secondary school. I thought, Shit, I’m stuck with it for life now.

It was an old Victorian school. In fact, it was that old that when I got to the fifth year they built a new school, a right concrete jungle, called Eaglesfield, and closed Bloomfield down.

But when I first arrived at Bloomfield, it was very scary. Remember, I was still weedy and couldn’t stand up for meself. Had no confidence, thought everyone was better than me. And so it was proved when I was streamed into the lowest class. And if you think it couldn’t get any worse, it did, ’cos I managed to come bottom of that class. I was the idiot, the kid who couldn’t read or write, the one they could pick on, bully and abuse. It was only later I discovered I was bloody dyslexic, or however you spell it. I’d do ‘b’ as ‘d’, ‘p’ as ‘9’, ‘6’ as ‘b’ and mix all the numbers up with the letters. I’d be physically sick if I had to do readin’ or writin’. That just wasn’t for me. Maths was the only thing I was any good at. It didn’t take me long to catch on to equations.

Ping – the rubber band came hurtling at me and hit me on me ear. Me fucking mastoid ear! I looked round; there was sniggerin’. After that came the assault with the 12 in plastic rulers; if you flicked the end up, then it come down with a bigger force – on the back of my hand. It stung. Things weren’t made any better by me mum, bless her, who insisted my uniform was always clean and my shirts perfectly ironed. The other kids must have thought I was stuck up, you know, a bit of a ponce. And, anyway, then disaster struck – I came top of the class. It was a total fluke – but nobody likes the number one bloke! I was in for it.

There was a group of about half-a-dozen boys, with this ringleader named Steve. He was a bit podgy but the tallest of ’em and, when you’re growing up, height is the one thing that matters. Soon as the bloody teacher was out of the room, they’d pick on me. It was a case of, ‘C’mon, let’s go and beat Stilksy up.’ They’d rush me. Bang! – in went a satchel; whack! – down came a ruler; slap! – that was the back of me head. Then the teacher would come back and they’d jump into their seats. I used to dread the teacher leaving the room ’cos then I knew I was in for it. I got my share.

Maybe ’cos I was new to the class, or I didn’t want to fight back – dunno, really – but I was the guy that got it. I think it’s because I never liked to join in any team sports on account of my ill health, so I was never really a part of a gang. I was more of a loner. Even now I don’t like team sports. I think real sport is on a one-on-one basis and, whenever the odds have been that, I rarely, if ever, lose. If you can’t win on your own, I’m not interested in playing. The bullyin’ would continue in the playground – maybe ten of ’em would come at me, taking me by surprise.

I can remember one day there was just me, the ringleader Steve and a mate of his, Steven, in this classroom. By now I was fucked off with being picked on, so for the first time I hit back. I clobbered this mate of Steve’s and he went right over. I dunno who was more shocked, him or me. And then there was like another voice coming out me mouth and I said to Steve, ‘And one day I’m gonna come back and do you as well.’

He laughed and said, ‘You’re fucking mad, Stilks. You’ll never do me. Even when I’ve got a walking stick, I’ll be doing you.’

I didn’t think any more about it and went back to me weedy ways until I was about 14 years old when you had to decide what subjects you wanted to take and what sports you wanted to play.

‘All those that want to do football over there,’ barked the teacher. ‘All those for tennis over there,’ he pointed. ‘All those for rugby, there.’

I was sitting down taking no notice. I was trying to do what I’d done for years, blend in and then bunk off ’cos it was Thursday afternoon sports period.

‘Stylianou.’

‘Sir.’

‘Stylianou, what sport are you going to do?’

‘Nothing, sir, I’m not well enough.’

‘You’ve got to do a sport this year, Stylianou, you’ve got away with it long enough.’

‘Football then, sir.’

‘Football’s taken.’

‘Rugby, sir.’

‘Rugby’s taken.’

‘What am I gonna do then, sir? I can’t do swimming because I can’t get water in me ear.’

‘You’re going to do judo, Stylianou. It’ll make a man of you.’

So I look over to see who was going to be doing judo and thought, Fuck me … nah … fuck me! – it was bloody Steve and all his bullying mates. They’d all wanted to do the fighting sport.

So I says, ‘No, sir, I don’t want to do judo, it’s not for me.’

‘You get over there, Stylianou. That’s what you are doing.’

I thought, Oh my God.

The judo lessons were given at Woolwich College in South London and the instructor was a fella called John Cole who is married to the sister of Brian Jacks, the Olympic judo medal winner. There was lots of sneering and taunting from Steve and his mob but John kept a tight rein on everything and there was fucking little they could do. But as soon as the lesson was over, I scarpered out of there first, in case any of ’em were trying to lay an ambush for me outside.

One week passed, two … three … four … and I was learning me holds and me throws. I was actually starting to bloody well enjoy it. Here was something at school I realised I liked doing. Then, one day, John said for the last ten minutes of the lesson we were all to practise with a partner. Of course, Muggins here got one of the bullies to partner. So I thought, Right, this is it. And lo-and-bloody-behold, the first thing I did was get him into a throw and bounce him down on the canvas. I was pushing him, pulling him, getting him in a hold … and a smile suddenly crossed my face. Fuck me, I thought, this kid isn’t as good and brave as he thinks he is.

The following week, the same thing happened. OK, they were throwing me as well, but I was dishing out as much as I was taking, even more most times. I was beating ’em. I’d started putting on weight a bit, but more importantly I was gaining confidence, I was starting to believe in meself for the first time my life.

Then, one day, we were in woodwork class and the chief bully Steve tells me to go and get something for him. He was always ordering people around, the nasty piece of shit. I said, ‘I ain’t gonna go and do nothing for ya. Fuck off.’

So he’s got a knife, and he’s come over, and he’s tried to stab me with the knife. So I grab his hand and start twisting it. But as I’m twisting it, hoping to hear it crack, the knife blade slashes across me … and he cuts me at the wrist. I manage to push him off and then says, ‘Right, after lesson I’ll see you outside.’ I was sounding like a cartoon character. One minute I was mild-mannered Stellakis Stylianou, and the next I was fucking Super Stilks.

It seemed all the class and their mates had gathered to see what happened in the playground. Strangely, the only one who seemed apprehensive was Steve himself. He was holding back while I went straight into the ring, me wrist strapped up with an old bit of bandage. I thought, Fuck it, and immediately took the fight to Steve. I grabbed him by his shirt, pushed, pulled and twisted him like we’d been taught, heard his shirt rip, then got him into a neat hold and threw him on the floor. I started picking him up to give him a bit more when I thought, He ain’t fucking worth it. So I threw him back on the floor, and that’s when I heard his head crack.

‘Don’t try messing with me ever again,’ I said. ‘And don’t forget to tell your mum how you got your fucking shirt torn.’

Now that I realised I could retaliate against anyone who threatened me, it must have gone to me head because I started to get unruly. I remember having the cane six times in one week. My judo was progressing, I was getting stronger and I was getting more and more into trouble. I became a nuisance; one of the kids disrupting the class all the time. I couldn’t hear much because of the mastoiditis, so I would sit at the back of the class and play up, doing me own thing and day-dreaming. In the end, the teachers started throwing me out of the classes until I was only allowed to take four subjects – Metalwork and Woodwork because I enjoyed ’em, and English and Maths ’cos I had to.

My Metalwork teacher was Terry Kilroy, who was head doorman at the Henry Cooper pub in the Old Kent Road and he would tell me these stories about his work as a bouncer which started to fire my imagination. He was also a British champion wrestler, so I’d always turn up at his class. But the other teachers didn’t want to know me. And I can’t fucking say I blame ’em.

With fuck all to do most of the day, I decided to set up a card school playing three-card brag. I’d find an empty classroom, get some of the other kids and we’d lock ourselves in. There were always about half-a-dozen of us and we’d play for money. Of course, I was still going home back to Wickham Lane where we lived as if I had been having a normal day at school, not gambling and beating people up. Mum kept on making sure my clothes were clean and fresh and tidy, so I suppose it came as a bit of a shock to my parents when I left school at 16 with no qualifications and I still couldn’t read or write.

‘Stellakis, doin’ all this judo and weight training ain’t gonna feed you,’ my dad would shout at me. ‘You’ve got to learn to read and write or when you’re older you’re gonna be banging your head against the wall. Sort your life out.’ He always went on like that, but I wasn’t listening.

When I wasn’t doin’ me sport, I was out nicking lead and copper wire from old houses and selling it. But Dad was worried about me and managed to get me an apprenticeship in Clerkenwell in London, near the City. It was nothing much. It was called McLauglin’s Machinery who made presses for the printers.

It didn’t last long, though. One day I saw these blokes humping this bloody machine outside.

The manager says to me, ‘Stilks, get out there and help ’em.’

I said, ‘It’s raining. I ain’t going out there. You go out in the rain.’

‘You go out there now or you’ll be sacked’

‘I tell you what – I’m fucking off home.’

And that was the end of me apprenticeship.

The next day, a letter arrived from the firm addressed to me dad. It said I was useless to the company, useless to meself and useless to anyone.

So I went on the dole with me mate Keith and with our first week’s dole money we bought a box of socks and we used to stand outside London Bridge. ‘’Ere ya go, six pairs for a pound, one for every day of the week – don’t care what you get up to on a Sunday!’ And then in the summer we’d knock out sunglasses, and that’s what we did for money.

Judo was my big love and I was taking extra lessons in the evenings; Tuesdays and Thursdays. I was rising up the ranks, as they say. That’s when I met Mick van Wyck. He was in the corner doing some curling with weights and told me it would improve me judo. And that fella later turned out to be Wolf from the Gladiators. But when I wasn’t practising, I used to hang out at St Peter’s Youth Club in Woolwich. I was always getting into trouble there and getting into fights. They used to have this pool table and people would put their money on the side for their turn next. I just used to walk by and scoop up the money and put it in me pocket.

One day, I was up to me tricks when this weird-looking guy came up to me and said, ‘Hey, what you doing taking my money?’

Now most people wouldn’t cause any fuss because me and my mate Mick ‘Scotty’ Lavell had a right reputation down there. But this weirdo who was in strange clothes like a hippy gone wrong had the cheek to talk back to me.

‘Fuck off,’ I said.

‘Come on, gimme my money.’

‘Bollocks.’

It went on like that for a bit, and this kid kept starin’ at me. He was a big bloke but he was dressed weird as shit. Anyway, I just snarled at him and moved off.

It was only years later that I realised I had been turning into the same kind of bully as Steve and his mates had been at school. They picked on me ’cos I was different and I was pickin’ on this kid ’cos he was dressing different and chose to be different.

So I’d like to apologise to him, and he knows who it is, ’cos it was George O’Dowd who later became Boy George. I reckon I owe him a week on the door for free whenever he’s playing. The offer’s open, George – sorry about that one, mate.

It was around that time I decided to take up boxing ’cos you could do it down St Peter’s Youth Club. So it starts off, first week skipping, second week shadda’ boxing, third week sit-ups and push-ups which I was doin’ all day long anyway. Well, I’d had enough of all this and said to the trainer, ‘Pat, I wanna do some fucking boxing!’

He looks round the place and says, ‘Do it with Les.’

I thought, Great, I can hit someone now. This is what I’ve wanted to do for ages.

So I get in the ring. Pat says to take it easy and move around. I’m doing it – jab, jab. This black kid two years younger than me goes – bang! – straight on me nose. So I’m moving around – bang, bang, jab. Then – bang! – another one on me nose. I’m thinking, He’s done that twice, I don’t like that. So I’m coverin’ up – jab, jab – and then he hit me again. Fuck this, every time I try and go for him he hits me on me fucking nose.

That was it – bollocks to it – I was gonna stick to judo in future. Anyway, the bloke I was fighting, Les Stewart, who was only about 14 then, later emigrated to Trinidad and became light-heavyweight champion of the world. He had forced me to give up boxing. If Pat had given me a different opponent at the beginning I might have become light-heavyweight champion of the world. But that was the end of me boxing ’cos I thought I wasn’t any good at it. Thanks a lot, Les.

Judo was my real big love and I was managing quite a high standard. Girls I didn’t have time for, and then one day I met Sheena, who would eventually become my wife. It was at a disco at a hall in Eltham. She was 15 and I was 18 and my mate says, ‘Have you seen that girl over there? She’s the best looking one here.’ So I’ve had a look and he bets me he can chat her up before I can. We had a bet and, for about six months, I followed her to different places, kept asking her out and she kept saying, ‘No, no, no.’

Then on Valentine’s Day I managed to get a date with her at the pictures. I was standing outside and I’d waited 20 minutes until I’d had enough and I was about to go. But as I was leaving, she turned up. I says, ‘Why are you late?’

She says, ‘I wasn’t late, I was early. I was waiting round the corner to see how long you’d hang around for me. Twenty minutes ain’t bad. Shall we go in and see the film?’

We hit it off right from the beginning but there was one thing I didn’t like telling her about. I was ashamed to let her know I couldn’t fucking well read or write. I thought if she found out, she’d drop me like that.

But I couldn’t hide it from her and one day she twigged when she found me looking at the Charles Atlas course I’d bought. I was trying to figure it all out just by looking at the pictures. It was the same with me other bloody body-building books. Great pictures, but I didn’t know what the fuck I had to do to get a body like that.

In frustration, I turned to Sheena and blurted out, ‘I’ll never develop meself, Sheena, ’cos I don’t know how to do the exercises. I can’t bloody well read the books.’

She was an absolute darling. ‘Don’t worry,’ she says. ‘I’ll teach you.’ And she did.

I’d look at the pictures in the magazines and she’d read out the words until I eventually started recognising ’em. Most kids might have started with bloody farm animals, but the first words I started to understand were ‘abdominals’, ‘biceps’, ‘hamstrings’ and ‘calves’.

And when it came to writin’, she’d make me write down my body-building work-outs and diet over and over again. ‘Reps’ must have been one of the first words I ever learned to write. Me mum and dad were well taken with Sheena.

By this time, me training was really coming along. With Sheena’s help, I was getting fitter, putting weight on and I’d joined a proper gym. I was pissed off with the Charles Atlas stuff. I was 6ft and 71kg. I was still very slim but I was wiry and my judo was getting so much better I started entering small tournaments. I had about five fights, won ’em all and I got into the final of this tournament. Who should I be up against but Neil Adams, who later won the silver medal at the Olympic Games.

He had already got a reputation and I thought, I don’t stand a fucking chance.

He had come from Manchester to train down in London and I just kept thinking, Shit.

So we’re on the mat and I’m pushing him and pulling him and I think, This is easy, I’m gonna beat him today. But, in fact, he was leading me into a false sense of security. The bugger reeled me in. He dropped his guard, let me come in and – slam! – we were on the ground. That, of course, was his speciality, but I didn’t know it at the time. He spun round and he got me into a strangle. And I thought, I ain’t gonna give in with all these people watchin’, I’m gonna get out of this …

And then I thought, What are all these people doing in my bedroom? And then I could hear the faint sound of something that was familiar but I couldn’t place it … I’m looking round … How many fingers can you see? … the sound getting louder … a rhythmic drone … I was going under again … I was going down again … Neil Adams had taken me out. He had strangled me until I was out cold, until I could hear that bloody sewing machine. And once again it was a nice experience. It was a weird feeling, the rush, the euphoria … And that was the only time I’ve ever been knocked out.

But even though I’d lost to Neil, I was beginning to impress a few people, and one of ’em was John Madden who, at the time, was top doorman in London and was, and still is, one of the nicest blokes you’ll ever meet.

He sent a friend of his named Don Austen, who was better known as Don the Docker, ’cos he worked at Tilbury, round to see me at the gym where I was building meself up and pressing some good weights.

‘You Stilks?’ he asks.

‘Yeah, who wants to know?’

‘You doin’ anything tonight?’

‘Not a lot.’

‘Wanna come over to the Music Machine and earn yourself some money?’

‘What’ve I gotta do?’

‘You gotta make sure Sid Vicious comes to no harm. He’s doin’ a personal appearance.’

I thought, Wow, Sid Vicious … Sid Vicious from the Sex Pistols. I’ve gotta make sure no harm comes to him.

Yeah, and then I realised … wasn’t he the one that was thin as a pin, white as distemper, had a major smack habit, and used to like ripping his chest open on stage.

Yes, that Sid Vicious.

I thought, Fucking hell. Make sure he comes to no harm! I’m probably too fucking late.