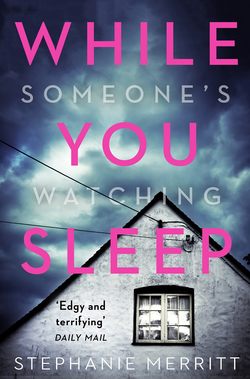

Читать книгу While You Sleep: A chilling, unputdownable psychological thriller that will send shivers up your spine! - Stephanie Merritt - Страница 7

1

ОглавлениеThe island appeared first as an inky smudge on the horizon, beaded with pinholes of light against the greying sky. As the ferry ploughed on, carving its path through the waves, the land took form and seemed to rise out of the sea like the hump of a great creature yet to raise its head. Bright points arranged themselves into clusters, huddled into the bay at the foot of the cliff, though the intermittent sweep of the lighthouse remained separate at the furthest reach of the harbour wall.

The only passenger on the deck leaned out, gripping the rail tighter with both hands, anchored by the smooth grain of the wood beneath her fingers. Doggedly the ferry rose and fell, hurling up a cascade of spray each time it crested a wave and dropped away. Wind whipped her hair into salt strands that stung her lips; she wore a battered flying jacket and pulled up the collar against the damp as she planted her feet, swaying with the motion of the boat, determined to take it all in from here as they docked and not through the smeared window of the passenger lounge downstairs, with its fug of wet coats and stewed tea. Outside, the wind tasted of petrol and brine. She pushed her fringe out of her face and almost laughed in disbelief when the noise of the engines fell away and the men in orange waterproofs began throwing their coils of rope and shouting orders at one another as the boat nosed a furrow through oily water to bump alongside the pier. Two days of travelling and it was almost over. She tried not to think about the old saying that the journey mattered more than the arrival. She tried not to think about what she had left behind, thousands of miles away.

The ferry terminus hardly warranted the name; there was a car park and one low, pebble-dashed building, the word ‘Café’ flaking off a sign above the door. She edged down the gangplank, pushing her wheeled art case in front of her and yanking the large suitcase behind like two unwilling toddlers, a travel easel in its holder unwieldy under her arm. Each time it hit the rail as she turned to wrestle with one bag or other, she was grateful that now, in mid-October, the ferry was not crowded, so that at least she did not have to worry about how many of her fellow passengers she had maimed in the process of herding her luggage ashore.

At the head of the slipway she saw a man in a leather jacket, its zip straining over a comfortable paunch. He was holding a home-made cardboard sign that read ‘Zoe Adams’; as soon as his eyes locked on to hers and met with recognition, he broke into a broad smile and started waving madly at her, as if he were trying to attract her attention through a crowd, though she was only yards away and the few remaining foot passengers had all dispersed. She smiled back, hesitant. He was around her own age, she thought; early forties, with thinning blond hair and a round, open face, cheeks reddened by island weather or a taste for drink, or perhaps both together. He approached her with an anxious smile.

‘Mrs Adams?’

She hesitated. She could have let it go, but there would only be more questions later on.

‘Uh – actually, it’s Ms.’

‘Eh?’

Zoe tilted her head in apology.

‘I’m not a Mrs.’

‘Oh.’ He looked afraid he had offended. ‘My mistake. You’re no married, then?’

She made a non-committal noise and set down one of her cases so that she could stretch out a hand. ‘You must be Mr Drummond?’

‘Mick, please.’ He beamed again, grasping her fingers and shaking them with a vigour intended to convey the sincerity of his welcome. ‘I’m the one who’s been sending all the emails.’ He released her hand and held up the sign with a self-conscious laugh; the wind almost snatched it from his grip. ‘My wife’s idea. I told her, it’s no as if there’s going to be hundreds of them pouring off the boat, but she said it would spare you feeling lost when you first set foot here.’

Zoe smiled. If only that were all it took.

‘It was very thoughtful of her.’

‘Aye, she’s like that. Kaye. You’ll meet her. Here, let me take those.’ He tucked the sign under his arm and hefted her cases into each hand, nodding across the car park to an old Land Rover, its flanks crusted with mud.

Zoe looked back at the harbour as he loaded her bags into the trunk. Through the lit windows of the ferry she could see the shapes of people cleaning, swinging plastic bags of trash, ready for the return trip, the boat garish in its brightness against the encroaching dark of sea and sky. The gulls shrieked their tireless warnings. Here, the rolling of the waves seemed louder and more insistent, as if the sea wanted to make sure you did not forget its presence. She wondered if she would grow used to that, after a while. A faint wash of reddish light stained the line of the horizon, but it was too overcast for a proper sunset like those in the photographs. Still, there would be time.

‘Hop in, then.’ Mick held the door open for her. For one panicked moment she thought he expected her to drive, before she realised she had made the usual mistake. That perverse habit of driving on the left. Perhaps she would get used to that in time, too. The quick flurry of palpitations subsided.

‘Is it far, to the house?’

‘Five miles, give or take.’ He glanced over his shoulder, shuffled his feet. ‘Look – it’s been a long journey, I know, and you’ll be tired, but we wondered if you’d like to come by the pub for a wee drink before I take you up to the house?’

Zoe began a polite refusal but he cut across her.

‘Thing is, we’ve music on tonight, local band, it’s a thing we do on Thursdays, so there’ll be a lot of folk out and we thought – well, it was Kaye’s idea – she thought it would be nice for you to say hello while they’re all in one place. Since you’re staying a while, you know. Only a wee glass.’ He twisted his hands together and looked at his boots before raising his eyes briefly to hers, as if he were asking for a date. ‘She’s dying to meet you,’ he added. ‘They all are.’

Zoe sucked in her cheeks. Christ. She was far from dying to meet them, whoever they were; quite the opposite. She felt grimy and dishevelled from the overnight flight, the five-hour train journey and two hours on the ferry; she probably didn’t smell too fresh either, under all her layers. And the point was to be anonymous here, to slip quietly into her coastal house and be left alone. She had not come here to make friends. But it had been naïve, she now realised, to imagine that a newcomer to a small community, out of season, would not immediately become a subject of gossip and speculation. If she was going to stay here a few weeks, it would be wise not to offend the locals on day one.

‘I’m not really dressed for going out,’ she said, though the protest was half-hearted.

‘You’re grand,’ Mick said, giving her a cursory glance. ‘It’s no as if they’ll all be in dinner suits.’ He clicked his seatbelt. ‘Just the one. And then I’ll run you up to the house, I promise. We can leave all the bags in the car.’

Zoe leaned her forehead against the window, the cold solidity of the glass reflecting her exhaustion back at her. Without make-up, the jet lag and all the sleepless nights of recent months were etched on her face, like a confession. Was that why she was so reluctant to go to the pub, she wondered – plain old vanity? Was it that she didn’t want to be judged by her new neighbours until she could at least brush her hair and paint some colour into her washed-out face? Of course, it could be a scam; she would blithely go in for one drink and when she came out there would be no sign of Mick or the car, or her bags. But if she was going to think like that, the whole thing could be a scam, as Dan had repeatedly pointed out. All she had seen was a website – an amateurish one at that – and a few emails. Maybe the house didn’t even exist. If that were the case, it was too late to worry about it now; she had already transferred the money.

‘Sure,’ she said, forcing enthusiasm. ‘Why not?’

‘Lovely. I wouldn’t hear the last of it from Kaye if we’d no given you a proper welcome.’ Zoe could hear the relief in his voice as the engine belched into life. ‘You’ll like it – they’re a colourful crowd. I mean – it’s no exactly the nightlife of New York,’ he added, as if fearing he might have created false expectations, ‘but then I suppose you’ve come here to get away from all that.’

‘I’m not from New York,’ Zoe said, watching the mournful lights of the café recede as he pulled away. Then, thinking she ought to offer something else, she added, ‘Connecticut. You’re not far off.’

‘Oh, aye?’ Mick turned out on to the main road. ‘Never been myself. America. I’d like to, mind. When the kids are older, maybe. Kaye wants to go to Nashville. She’s into all the country music and that, you know? Now me, I’ve a fancy for somewhere more rugged. Hiking, fishing, that sort of thing. I’ve always liked the idea of moving to Canada.’

‘So does half my country right now,’ she muttered.

‘Aye, the great outdoors,’ Mick continued, missing the point. ‘That’s where I’m at home. Can’t get my girls interested yet, though they’re quite into animals and all that. We get otters up here – you’ll maybe see some around the bay.’

Zoe leaned against the window and let Mick fill the silence with his wilderness dreams. For as long as he was talking about himself or otters, he was not asking her questions. They passed through what she assumed was the main street of the town: a general store; a place that sold hardware, electronics and fishing supplies; a tea room; a bookshop; a few vacant shopfronts, the windows opaque with milky swirls of whitewash as if to veil their emptiness from public view. At the far end, the street broadened out into a triangular green with a war memorial in the centre, a school playground on one side and a small, plain church opposite. Mick swung the Land Rover to the right, past the churchyard, into a narrower lane. The cottages on each side lined up crookedly against one another, like bad teeth, but they looked snug, with lights glowing warmly behind drawn curtains.

‘Have you always lived here?’ she prompted, when he seemed in danger of running out of talk. He slid her a sideways look and she sensed that a certain wariness had descended.

‘Born and bred,’ he said. She was not sure if the note in his voice was pride or resignation. ‘Got away as soon as I could, mind. All the young ones do. But my mother passed away five years back and my da couldn’t manage the pub on his own, he was getting on, you know? So I came home. Brought my wife and daughters with me.’ He heaved a deep sigh. ‘Sometimes a place is in your marrow. It pulls you back. Nothing you can do about it.’

‘Uh-huh.’ Zoe nodded. ‘My grandmother came from this part of the world, actually.’

‘Is that right?’ He eyed her with greater approval. ‘So you’ve come in search of your roots?’

‘Something like that. I guess my Scottish blood’s pretty diluted by now. She married an Englishman. My mother grew up in Kent. I was born there too.’

‘I’d keep that quiet round here, if I were you.’ He winked. ‘You don’t sound like you’re from Kent.’

‘We moved to the States when I was a kid. My dad’s from Boston.’ She wrapped her arms around herself; the thought of her father speared her with a sudden pang of longing. No use thinking of that now. She forced a brightness into her voice, changing the subject. ‘So did the house always belong to your family? The one I’m staying in?’

Again, that slight hesitation, the flicker of a glance, as if he suspected her of trying to catch him out.

‘Aye.’ It looked as if this was the extent of his answer, but as they approached a turning with a painted sign at the entrance showing a white stag on the crest of a hill, he cleared his throat. ‘But it didn’t come to me until my father passed on last year.’

‘Oh, I’m sorry,’ Zoe said automatically. ‘About your father.’

‘Aye, well, he was eighty-seven and still working, more or less – that’s no a bad run.’ Mick sniffed. ‘But he’d let the house go over the years. They all had. Took a lot of work to make it fit to live in. Don’t get me wrong’ – he turned to her with that same anxious expression – ‘it’s all good as new – better. I did most of the work myself – that’s what I used to do, down in Glasgow, you know – restore houses. It’s lovely now, though I say so myself. Well, you’ll have seen the photos on the website. They’re no Photoshopped or any of that,’ he insisted, a touch defensive.

‘It looks beautiful. You didn’t want to keep it for your family home?’

He snapped his head round and his eyes narrowed. Then his face relaxed and he laughed, almost with relief. ‘Too far out for us. We stay here, above the pub. That way we’re on hand if there’s any problems. And the girls can walk to school in five minutes. That’s the only reason,’ he added, as if someone had suggested otherwise. ‘No sense in making life more complicated.’ He indicated the building in front of them, a whitewashed inn of three storeys with gabled windows in the roof. The car park outside was busy, and as he switched off the engine, Zoe heard music and laughter drifting through the clear air. ‘But if it’s peace and quiet you’re after, it’ll be perfect for you.’

He was trying too hard, Zoe thought. Perhaps there was something wrong with the house after all. It had looked so idyllic on the website; eccentric, as if the original architect had thrown at it all the excesses of the Victorian Gothic and hoped for the best. From the pictures she had seen, the interior was tastefully restored and minimally furnished, but what had really hooked her was the light. The photographs had been taken in summer, but even in sunshine there was a bleakness to the island’s beauty that had whispered to her, stark bars of cloud lending shadow and depth to the sky. A veranda ran around the west and south sides of the house, overlooking an empty strand of sand and shingle, marked only by coarse clumps of seagrass, tapering down to a small bay that gave on to the vast silvered expanse of the Atlantic. The house was set a little way back from the beach, built into the slope of the cliff at its shallowest point, while a ridge of rock rose up behind, as if to protect it from prying eyes. She had noticed the quality of the light with a painter’s eye, and known with some instinct deeper than thought that she needed to wake under that sky, to the sound of that empty ocean and the seabirds that wheeled and screamed above it, if she was ever going to find her way back. Whether some ancestral tug in the blood had drawn her there, she could not say. She had only felt a certainty, on seeing the house, that had eluded her for months; the knowledge that it was meant for her.

‘Peace and quiet is absolutely what I want,’ she said, but with a smile, so as not to seem antisocial.

Mick opened his door, then turned back to her. ‘The thing is, Mrs Adams – Ms – sorry, Zoe …’ He chewed his lip, unsure how to continue. ‘There’s a lot of history to this place. Legends, and so on. And a lot of families have been here for generations. So people have their superstitions, you know? Plenty of folk here have barely been off the island.’

Zoe nodded. ‘I guess that’s part of the charm.’

‘Aye, but …’ He looked uneasy. ‘It’s only – if you hear people telling tall tales, as they like to do with a drop of whisky inside them, pay them no mind. Fishermen’s yarns, old wives’ gossip – that’s all it is.’

‘Oh, I love all those folk tales. My grandmother used to tell them when we were kids. Selkies and giants and whatever.’ As soon as she’d said the words, she regretted them, picturing herself trapped in a smoky corner by some ancient mariner.

‘As long as you know that’s all they are. Bit of fun. Tease the incomers.’ Mick smiled back, but he did not look reassured. ‘Come on then, you must be gasping for a drink.’

The warmth of the pub hit her face like a blast from a subway vent, thick and yeasty, homely smelling: woodsmoke and winter food, stews, hot pastry and mulled cider. A wave of sound broke over her at the same time, a fast and furious jig from the band, accompanied by raucous singing, foot-stamping and the banging of beer mugs, so that for an instant Zoe felt overwhelmed by the force of it, the noise and heat and smell of so many people crammed into a lounge bar designed for half their number. She stood very still, one hand to her temple as if her head were fragile as an eggshell, and closed her eyes as the weight of her jet lag settled inside her skull. When she opened them, every head had swivelled to stare at her. She allowed her gaze to travel the room, taking in the questioning faces – no hostility in them, as far as she could see, most had not even missed a breath in their singing – and felt her own expression freeze into a tight little smile, fearful of offending. She cast around for Mick with a flutter of alarm, until she realised he had flipped open the bar and taken up a position of natural authority behind it. He beckoned her over and pushed a heavy crystal tumbler across the polished wood. A generous measure of Scotch glowed honey-gold, with no ice.

‘Get this down you,’ he said in a low voice. ‘Put some colour in your cheeks.’

Zoe lifted the glass to her mouth and breathed in peat and smoke, ancient scents, the land itself. The heat slid down her throat and uncurled through her limbs. Behind her eyes the headache intensified briefly, then began to melt away. She set the glass down on the bar and Mick immediately refilled it, with a wink.

‘That’s my Kaye there,’ he said, nodding to the makeshift stage where the band were building to a crescendo. Zoe turned to look. The singer was a buxom woman dressed younger than her age, in drapey black skirts and a black lace top, her long pink hair bright and defiant. She sang with her eyes closed, a fist wrapped around the microphone, one foot in floral Doc Martens pounding the stage to the beats of the bodhran, her voice bluesy and hard-edged, smoke and whisky. Though Zoe could not make out the words, she surmised from the ferocity of the singing that it was some kind of nationalist rebel song, and that the anger soaked through its lyrics was still keenly felt by a good many of the patrons.

The rest of the band were men; all – apart from the young fiddle player – well into middle age, with grey hair pulled back into ponytails, and grizzled beards, leather waistcoats and cowboy boots. There was an accordion, a pennywhistle and a guitar as well as the bodhran and the violin; the music sounded vaguely familiar, the kind she had heard on a loop in Irish bars in Boston and New York, but here it did not feel manufactured for tourists. The musicians played with their eyes closed, as if every note mattered.

The rebel song ended in a burst of cheering and applause, but the band did not even pause to acknowledge it; instead the woman launched into a wild and wrenching lament, accompanied only by the violin and the heavy heartbeat of the drum. The room stilled to a reverent hush as her voice soared to the blackened rafters, transformed now into a fluting, other-worldly alto, holding tremulous notes that made goosebumps prickle along Zoe’s arms and the back of her neck. Though she did not understand the strange language, she could not miss the heart-cry in the music: a grief that seemed centuries old. Looking around, she saw old men with tears running down their faces, mouthing the words to themselves. The woman’s voice faded out and the young fiddle player stepped forward for a solo, his lips pressed tightly together, slender fingers moving nimbly over the strings, brow furrowed behind the long fringe that fell over his face. Zoe sipped her second whisky and experienced a sudden urge to reach forward and brush it out of his eyes, the way she would with Caleb when he was bent over his iPad, absorbed in whatever animation he was making, oblivious to everything. She became aware that Mick was leaning over the bar behind her, a dishcloth pressed between his clasped hands.

‘She has an incredible voice.’ Zoe realised she was expected to comment.

‘She’s something, isn’t she?’ Mick said, not taking his eyes off his wife. That glimpse of tender pride caused Zoe to flinch briefly. She remembered seeing the same expression on Dan’s face, at the first exhibition she had invited him to when they started dating; admiration of her talent and the thrill of being allowed to claim some share in it. She could not remember when he had last looked at her like that.

At the end of the song, the band set down their instruments and announced a break. Around the bar the hum of conversation resumed; glances once more directed openly at her, murmured observations that made no effort to disguise the fact that she was the subject. The woman with the pink hair sprang down and pressed her way across the bar, scattering smiles to left and right. She stopped breathlessly and caught Zoe’s hand between both of hers.

‘Zoe! We’re so glad you’re here. I’m Kaye Drummond. I hope he’s got you a drink? Top her up there, Michael, will you? You’re our guest tonight. Are you hungry?’

Zoe shook her head. If she had been hungry, the whisky had blunted all memory of it. Kaye looked up at her with anxious eyes. Though her figure was voluptuous, her face was delicate, almost elfin, the wide blue eyes rimmed with black kohl, her rosebud mouth painted the same shade of fuchsia as her hair; Zoe guessed her to be in her late thirties. She wore large silver rings on every finger, so that Zoe felt she was being clasped by armoured gauntlets.

‘That was a beautiful song just now,’ she said.

‘Oh, aye, thanks.’ Kaye beamed, her eyes shining. ‘It’s an old one. Everyone round here remembers their granny singing it.’

‘What does it mean?’

‘Och, they’re all awful depressing. It’s about a woman who loses her love to the sea and drowns herself of a broken heart. Most of them are, if they’re not about the Clearances. People have long memories up here. Have you come to paint? I said to Mick, we could have a wee show here in the pub if you wanted. Folk might like to see them. They might even buy one, if they weren’t too …’ she made a knowing face and rubbed her thumb and forefinger together.

‘Oh – that’s kind, but …’ Zoe felt herself growing flustered. ‘I hadn’t thought of selling. I’m a little out of practice. I’m here to find my way back to it, I suppose.’

‘Well, you let us know,’ Kaye said, undeterred. ‘It’s no like we’re experts. They could be total shite, we wouldn’t know any different.’ She broke into peals of laughter and flicked Zoe on the arm with the back of her hand. ‘I’m only messing with you. I’m sure they’re no shite. You’d buy one, wouldn’t you, Ed?’

She nudged the young man next to her, the fiddle player, in the ribs. He turned from the bar and gave Zoe a shy smile from under his fringe. He wore large tortoiseshell glasses that reflected the light, making it hard to see his eyes clearly.

‘Buy what?’

‘One of Zoe’s paintings.’

‘Oh. Well – ah – what are they of?’

‘I haven’t done any yet,’ Zoe said, smiling to ease his embarrassment. ‘Well – not here. But I guess I paint landscapes. Or I used to. Kind of impressionistic. Not very original,’ she added, with an awkward laugh.

He shrugged. ‘Everyone likes a landscape, don’t they? I mean, at least you know what it is. People don’t stand around in galleries arguing about what a landscape means, right?’

Oh, they do, Zoe almost said, but stopped herself; condescension would not be a good look. The boy took off his glasses and rubbed them on the hem of his shirt; his face appeared soft and exposed without them. A pint of dark beer was slopped down on the bar top in front of him. She glanced up and caught the eye of the barmaid, a thickset girl of about eighteen with heavy make-up, a top that was too tight to flatter and dyed black hair scraped into a messy topknot, pulling her small features taut under ruthlessly plucked brows. She looked at Zoe with evident disdain, even when Zoe ventured a smile.

‘Cheers, Annag.’ The boy, Ed, replaced his glasses, took a sip from the top of his pint and fished in his pocket for coins with the other hand. She noticed he did not look at the girl behind the bar. Instead he cocked his head towards Zoe. ‘Can I get you a drink?’

She glanced down at her glass. While her back had been turned, it had magically acquired another two fingers of Scotch. She would have to take it easy; already a gentle numbness had begun spreading up the side of her face, warm and comforting, as her head was growing lighter.

‘I’m good, thanks.’ She hesitated. The barmaid continued to watch her. ‘I’d take one of those, though.’ She nodded towards the open breast pocket of his shirt, where a pack of Marlboro Lights nosed out. As soon as she’d asked, she wondered why she’d done it. She hadn’t smoked for over a decade, not since before she was pregnant with Caleb. She hadn’t even been aware that she’d missed it. She had a sudden memory of the first day of college, self-consciously lighting a cigarette almost as soon as her parents had driven away, because for the first time there was no one who knew her and she was at liberty to try out a new version of herself, one less timid and constrained by expectations. Perhaps this was the same thing, twenty-five years on. Dan would be appalled. She supposed that was precisely why she had asked.

‘Course.’ The boy picked up his pint and patted the cigarettes in his pocket. ‘We’ll have to go out the back.’

As she turned back for her drink, Zoe saw the look of naked hostility on the barmaid’s flat face and realised, too late, that she might unwittingly have stepped on someone’s toes.

‘I don’t really smoke,’ she said, by way of apology, as the boy held open a door at the side of the bar and led her through to a paved courtyard that opened on to a grassy area with picnic tables overlooking a low wall. Beyond this, some way below them, lay the vast black expanse of the sea.

‘Nor do I.’ He flipped open the pack and offered it to her, glancing around as he did so. ‘At least, not where the children might see me.’

She looked at him, surprised. He could not be past his early twenties. People started younger in the country, she supposed. ‘How many kids do you have?’

‘Eleven.’ He left a significant pause, grinning at her expression. ‘Youngest four, oldest nearly twelve. I’m the schoolteacher here.’

‘Oh.’ Zoe laughed, to show that she had fallen for the joke. She regarded him with a new curiosity. ‘Just you?’

‘Just me. There’s only one class. The older kids take the ferry to the mainland and board during the week.’

‘Wow. How long have you been here?’

‘Since Christmas. The previous teacher had to retire on health grounds, they needed someone quickly. I was lucky. It’s my first job out of college.’ He gave a diffident smile and struck a match, cupping his hands around the flame as he brought it to the tip of her cigarette. He leaned in close enough for her to see the fine dusting of freckles over the bridge of his nose. Behind his glasses, his lashes were so long they brushed the lenses, and dark, darker than his hair. He sensed her looking and raised his eyes; a gust of wind snuffed out the flame before it could make contact.

‘What made you choose somewhere so remote?’ she asked quietly, as he threw down the burnt match and struck another.

‘I could ask you the same thing,’ he said. He laughed as he said it, but she glimpsed a flash of wariness in his eyes. The match guttered out and he dropped it with a soft curse.

‘Running away,’ said a firm voice behind them. Zoe jumped, as if caught in a forbidden act; she whipped around to see a man seated on a bench by the door, against the wall of the pub, almost hidden by shadows. He spoke through a pipe clamped comfortably between his teeth. A black Labrador lay at his feet, half under the bench, so dark its hindquarters seemed to disappear. ‘Everyone who comes here is trying to escape from something,’ he repeated, amusement lighting his eyes. ‘And those who were born here dream of running away.’ He rubbed his neat white beard and smiled, as if they were all included in a private joke. ‘Here, Edward –’ he held out a silver Zippo – ‘you’ll be there all night with this wind.’

The boy stepped forward to take the lighter. ‘What are you running from then, Professor?’

The older man considered. ‘History,’ he said, after a pause. His gaze rested on Zoe. ‘And you must be the artist from America. We’ve been looking forward to meeting you.’ He did not speak with the local accent, but in the rich, sonorous voice of an English stage actor. A reassuring voice, Zoe thought.

She inclined her head. ‘Zoe Adams.’

‘Charles Joseph.’ He held out a hand, though he didn’t get up, obliging her to cross to him so that he could shake hers with a brisk grip. Even in the half-light she could see that his face was tanned and weathered, his eyes a sharp ice-blue. He could have been anywhere between fifty and eighty. ‘And this is Horace. Named for the poet. He has a decidedly satirical glint.’ The dog raised its eyebrows and thumped its tail once in acknowledgement.

‘Are you a professor of history, then?’ she asked, to turn the conversation away from herself.

He laughed. ‘I’m afraid this young man is flattering me. Or mocking me, I’m never sure which. I have been a university teacher in my time, it’s true, though I never held tenure. Never stayed anywhere long enough.’

‘Everyone calls him the Professor, though,’ Edward said, cracking the Zippo into life. Zoe held her cigarette to the flame, inhaled and coughed violently as her head spun. ‘He’s our local historian. Anything you want to know about the island, he’s your man.’

‘Well. I can’t promise that, but I can usually find a book to help.’ Charles Joseph puffed on his pipe and folded his arms across his chest. ‘I own the second-hand bookshop on the High Street. Do drop by sometime. I make excellent coffee and it gets quiet out of season. I’m always glad of a visitor.’ Pale creases fanned out from the corners of his eyes, Zoe noticed, as if he smiled so often the sun had not had a chance to reach them.

‘He’s being modest,’ Edward said, breathing out a plume of violet smoke. ‘He’s the one who wrote most of the books. Get him to tell you the island’s stories. He can talk the hind legs off a donkey, mind.’ He grinned at Charles. Zoe sensed an unspoken affinity between these two men, despite their difference in age. Perhaps it was a matter of education; in a community like this, those who read books tended to huddle together against the corrosion of a small-town mindset. That was how it had been where she grew up, anyway.

‘My price is a cinnamon bun from Maggie’s,’ Charles said, lifting the pipe out of his mouth. ‘That’s the bakery three doors down from my shop. Bring me one of those and I’ll tell you all the tales you have time for.’

Zoe thought of Mick’s hesitant warning in the car, about the locals and their legends, embellished to frighten incomers. She took another drag, the second easier than the first, and felt the nicotine buzz through her blood.

‘How do you know so much about the place?’ she asked.

‘I lived here for a while, many years ago.’ Charles paused to relight his pipe. After considerable effort and fierce puffing, he looked up at her through a cloud of smoke. ‘After I retired, I drifted back. I think I always knew I would, deep down.’ He made it sound fatalistic, the way Mick had.

‘You missed it?’

‘It called me back. Simple as that. I took a look around and it occurred to me that people here could do with a bookshop.’ He drew on his pipe again with a rueful smile. ‘Not many of them agreed, if my accounts are anything to go by.’

‘Rubbish,’ Edward said. ‘People love the bookshop. Your profit margins would be a lot better if you weren’t always giving books away for nothing.’

‘Well, that’s the trouble, you see.’ Charles leaned forward, pointing the stem of his pipe at Zoe as if he were imparting a confidence. ‘Whenever someone comes in, I think, a-ha, I know just the thing he or she should read. But people have very fixed ideas about what they think they like – have you noticed? Sometimes I have to fairly insist they take it, and then I can hardly charge them. But I’m almost never wrong – Edward will tell you. Besides,’ he sucked on the pipe and sighed out a fragrant haze, ‘I hate to see books sitting alone and unloved on a shelf. I’d much rather they found a home.’

‘Not the smartest way to run a business,’ Edward said, with affection. Charles inclined his head.

‘True. But only an idiot would open a second-hand bookshop to get rich.’

‘Did you live here as a child?’ Zoe asked.

Charles looked at her, his white eyebrows gently puckered, as if the question required careful deliberation.

‘There you are!’ The door banged against the wall and Kaye stood on the step, a pint glass of water in one hand, jabbing a finger towards Zoe in mock-admonishment. ‘Thought we’d lost you.’

Zoe saw her take in the cigarette and felt immediately guilty, as if she were still her adolescent self and had exposed herself to the censure of the neighbours. Kaye’s look changed when her gaze fell on Charles, stretched comfortably over his bench, Horace’s chin resting on his boots.

‘Has he been filling your head with nonsense?’ She nodded towards him. She was trying to keep her voice light, but Zoe did not miss the underlying sharpness, the anxiety in Kaye’s eyes.

‘None that wasn’t there before,’ Zoe said with a smile.

‘He’s a great one for the stories, is our Professor,’ Kaye said, fixing him with a stern eye. ‘Keeps us all entertained round the fire when the nights draw in. Ed – Bernie wants to go in five. Give us a drag of that.’ She took Edward’s half-smoked cigarette from his hand without waiting for an invitation, throwing a guilty glance towards the upper windows of the building behind them. ‘If my girls are looking out, I’m in trouble.’

She hauled in another lungful and leaned down to stub out the butt in a pot of sand by the door. Edward dug his hands into his jeans pockets and dipped his head towards Zoe. ‘Nice to meet you. Hopefully we’ll see you up here again, if you’re around for a while.’ The diffident angle of his glance, the not-quite-meeting of her eye, the studied nonchalance of his tone, all caught Zoe off guard; was he flirting with her?

‘Sure,’ she said, aiming to sound neutral. The idea seemed so unlikely that almost as soon as it had occurred she felt embarrassed by it, in case he had guessed at her presumption. He nodded, gave Charles a brief wave and disappeared back inside the pub. Kaye beamed widely and looked at the door, as if she could will her guest back inside with the force of her smile. Zoe was too foggy with tiredness to offer any resistance. She looked at the cigarette burning slowly down between her fingers as if she couldn’t remember how it had come to be there. She ground it out in the sand and turned back at the door to Charles.

‘I’ll look out for your shop, Mr Joseph.’ She did not quite have the nerve to call him ‘Professor’.

‘Please do,’ he said, reaching down to tousle the dog between its ears. ‘Horace and I are there every day, putting the world to rights with whoever drops by. We’d be delighted to see you. I promise I’ll find you an interesting read.’

A brief twitch of alarm passed across Kaye’s face. ‘Mind you behave yourself,’ she said, pointing at him. ‘Mrs Adams is our guest.’ Once more, the jokey tone, with the undercurrent of warning. It was curious, Zoe thought; Kaye obviously liked the Professor, but she seemed keen to keep him away from her, without ever quite making it explicit. Did she fear he might tell her some local legend that would spook her so much she’d run away tomorrow and shout it all over TripAdvisor? She almost laughed, that they could think her so skittish. They had no idea; no story could be worse than the one she carried with her. Besides, she had already paid half the rent up front.

‘I like history,’ she said to Charles. ‘And poetry.’ Her tongue felt thick and woolly in her mouth as she spoke. She looked down at the glass in her hand and realised it was empty; she did not remember drinking it. She felt Kaye’s solid presence at her back, ushering her firmly but gently indoors.

After the night air of the courtyard, the heat of the log fire and the press of bodies crowded in on her. The whisky churned in her empty stomach and the nicotine pulsed in her temples, dizzying her and blurring her vision. She leaned against the wall, briefly closing her eyes. Her skull seemed to squeeze tighter and she took a deep breath to quell the nausea. Though she had no interest in making friends here, she did not want to be known forever as the woman who threw up in the bar within an hour of arriving.

‘You all right?’ Kaye laid her metalled fingers lightly on Zoe’s shoulder.

Zoe nodded. ‘The bathroom?’

‘Past the bar, on the right.’ Kaye patted her, as you might a small child.

The bathroom was even more stifling, airless with the heat of hand-driers in a confined space. Zoe took off her flying jacket and tucked it between her knees, splashed cold water over her face and dried it with the sleeve of her shirt. She rested her forehead against the cool of the mirror and watched as her breath fogged a circle on the glass. Her reflection stared back at her with frayed outlines. Her skin looked blanched, the shadows beneath her eyes so deep they appeared bruised. She had taken her make-up off before the flight and been too tired to bother applying any more. Straight off the red-eye, Bradley to Dublin, connecting flight to Glasgow and on to a five-hour train journey to the ferry, to bring her here. When she had planned it, back home, it had seemed a good idea: get all the travelling done at once, no layovers, no breaks for sightseeing. She was not here for tourist attractions. All she wanted was to get to the sprawling old house by that deserted shore that had called to her over the Internet, and wrap its solitude around her. She had no sense of time any more; she struggled to remember when she had last eaten, or showered.

Rubbing away the condensation of her breath with a sleeve, she met her reflection’s eye with as steady a gaze as she could manage. They both seemed disappointed with each other. Turning forty-three, and looking every last day of it. Did she seriously imagine that earnest, handsome boy would have been flirting with her? But it was more than jet lag, she thought, peering closely at her own face in the mirror; all the turbulence of the past year was written into her skin, a bone-deep exhaustion she could not shake off. Perhaps here she would finally be able to sleep.

She fished in her pocket and found a Chanel lipstick, one she had thrown in at the last minute, just in case. In case of what? What occasions to dress up had she imagined would present themselves on a small island off the west coast of Scotland, in winter? She barely wore lipstick even at home. Perhaps it was a defensive measure, a reaction against all the military-coloured hiking gear and shapeless sweaters she had packed. One last vestige of femininity. She opened her lips and slicked it around them, blotting the colour on a sheet of toilet paper. Not too garish; a discreet reddish-brown that she used to think suited her but now seemed to drain all the colour from the rest of her face. She wondered how soon she could reasonably ask to leave.

The door opened; Zoe glanced up and saw that another face was staring at her, unsmiling, in the mirror. The young barmaid, Annag, reached up and adjusted the pineapple of hair balanced on her crown, her eyes critically appraising Zoe all the while.

‘You’re the one who’s taken the McBride house.’ The girl’s accent was broad, rough-edged. ‘Brave,’ she added, cocking one thinly pencilled brow with an air of challenge.

‘It’s Mick and Kaye’s house, I thought,’ Zoe said mildly. ‘Aren’t they Drummonds?’ She did not ask why she should be considered brave, precisely because she could see that the girl was dying to tell her.

‘It’ll always be the McBride house round here,’ Annag said, with a meaningful look. She had an oddly flat face, Zoe thought, and wide, with all the features cramped together in the middle, like a puppet of the moon she had once seen in a kids’ show. Too pale for that unnatural shade of black dye, she added, in her head. This girl’s attitude seemed to provoke a mean streak in her, as if they were both in high school.

‘I’m afraid I can’t pronounce its real name,’ she said, forcing a smile.

Annag muttered a word deep in her throat that Zoe assumed was Gaelic, but sounded nothing like the way it looked on paper. ‘It means “resting place”,’ she said.

‘Oh. That’s nice.’

‘You think?’

Zoe looked up and saw that the girl was smirking openly. A strange chill ran through her as she understood. Clearly, the person who named the house had not stopped to consider its double meaning. Or perhaps they had.

‘Give us a lend of your lippy.’ A pudgy hand stretched out towards her, open; bitten fingernails painted flaking green. Zoe hesitated. Was this a normal thing to ask a stranger? She had grown up without sisters, without a close group of girlfriends; as a result she was possessive about her belongings and a little fastidious, bewildered by the kind of women who presumed all feminine items should be held in common. But she couldn’t think of a good reason to refuse without implying that she considered the girl unhygienic. Reluctantly, she passed the lipstick over. Annag stretched her mouth wide, drew on a red circle, smacked her lips together and pouted, apparently pleased with the result.

‘Why am I brave, then?’ Zoe asked, as if this small intimacy might now entitle her to answers. ‘I guess it’s haunted or something, right?’ She tried to make it sound jokey, as if she were happy to play along, but a look of guilt slunk over Annag’s moon face. The girl concentrated on the lipstick, twisting it all the way to the top and down again.

‘I only meant – staying out there on your own. In the middle of nowhere. That’s brave, for a woman.’ She reached inside her top with one hand and twanged a stray bra strap into place. ‘Not that I’m saying— I don’t mean …’ She turned to look at the real Zoe beside her, instead of at her reflection. ‘Whatever folk say about it, you didnae hear it from me, okay? Mick’ll bloody kill me.’

So Mick had warned this girl about telling whatever tales clung to the house. Had everyone else in the town been given a warning too? Charles Joseph apparently had, though he didn’t seem to feel inhibited by it. What could be so terrible that Kaye and Mick genuinely feared it might drive a tenant away? It will be one of those stories like the ones people used to swap at high school slumber parties, Zoe thought: like the one where the girl hears the banging on the car roof and it turns out to be her boyfriend’s head. And that’s what you get for coming to the ass-end of nowhere, she reminded herself: people who take that stuff seriously. But she found that, however dumb the story might be, she didn’t want to hear it on her first night.

‘But I haven’t heard anything,’ she said.

‘Then you’ll sleep soundly in your bed, won’t you?’ Annag flashed her a smile that seemed to contain some element of private triumph, before walking out. As the door banged behind her, Zoe realised Annag still had her lipstick in her hand. She considered going after her, asking for it back, but decided against it. There was no point making an enemy of this girl, who already seemed to resent her presence. But if she was honest, it was because Annag reminded her of the hard-faced girls who had given her hell in high school, and she despised herself for her own cowardice. She made a note to stay out of the barmaid’s way as far as possible. Out of everyone’s way. She caught her reflection’s eye with weary contempt, and slowly wiped away the bright slash of lipstick with a tissue.

Even in the dark, the house looked imposing. Mick had installed motion-sensor security lights at the front; a white glare leapt out of the blackness like a prison searchlight as the Land Rover descended the last slope and rounded the curve of the drive, Mick raising a hand to shield his eyes and swearing under his breath. They lit up a rambling house of three storeys, tall Gothic windows along the first floor, diamond-paned glass, pointed eaves over the windows in the attic, several tall chimneys and a hexagonal turret jutting up from the roof. A warm light glowed from one of the windows on the ground floor. As Zoe swung herself down on to the gravel, she could hear the booming of waves in the darkness beyond the house.

‘Kaye’s left you a few bits and bobs – bread and milk and whatnot,’ Mick said, lifting her suitcase down from the trunk. ‘Should see you right for breakfast. She’s done a wee folder too, telling you where to find everything – it’s got our number on and a few others you might need. I was thinking I could come by tomorrow before lunch and show you the other stuff. How the generator works, where we store the logs, all that business. Then, if you like, I’ll bring you into town so you can go to the supermarket.’

Zoe murmured her thanks, only half listening. She craned her neck and stared up at the night sky. A brisk wind chivvied scraps of cloud across the face of the moon; behind them, an extravagant scattering of stars glittered across ink blue wastes. The seabirds sounded subdued here, their cries reproachful. ‘Why do people call it the McBride house?’

Mick froze, for a heartbeat, in the act of setting down her art case. ‘McBride was the fella who built it, back in 1860.’ He sounded unusually stiff.

‘Was he a relative?’

‘He married my great-great-aunt. It passed to her brother, my great-great-grandfather. Been in my family ever since. But the name stuck. Now,’ he said, forcibly cheery, ‘let’s get this lot inside and you can settle in.’

He carried her cases into the wide entrance hall, set them down at the foot of the stairs and immediately flicked on all the lights he could find. Inside, the house smelled of new paint, furniture polish and the heavy floral scent from an extravagant vase of lilies that stood on a wooden chest opposite the front door.

‘Beautiful flowers,’ Zoe remarked, to fill the silence.

‘Oh, aye. Kaye did those.’ Mick seemed distracted, his eyes flitting around the hallway as if he half expected to see someone appear from one of the doors leading off it.

‘That was such a kind thought – will you thank her?’ It was gone eleven, by the grandfather clock in the hall; Zoe had lost all track of what time her own body thought it was, but the whisky sat heavy in her stomach and she was struggling to keep her eyes open. She wished he would hurry up and leave.

‘I will. Well, then. There are your keys. Those are the front door. The ones for the back are on a hook in the kitchen.’ Mick dropped a weighty keyring into her palm, dug his hands into the pockets of his leather jacket, then took them out again as if unsure what to do with them, glancing back at the front door. He seemed reluctant to go, but at a loss as to how to prolong his visit. For one awful moment, Zoe wondered if he was hovering for a tip, but it didn’t seem likely. ‘Shall I take these up for you?’ he asked, his gaze alighting on the cases.

‘Oh, no, I can manage,’ she began, but he was halfway up the stairs, telling her it was no trouble.

‘Well, then,’ he said, when he returned. ‘I suppose I should let you get on. The water from the tap’s fine to drink, by the way. And you remember there’s no broadband? I mentioned that in the email.’

‘It’s fine. It’ll be good for me to get offline.’ She forced a smile.

‘They haven’t got the cables out to this side of the island,’ Mick explained, keen to make clear it was no failing on his part. ‘In the next year or so, they reckon, not that that’s much help to you. You can come and use ours up at the pub if you want to send emails and whatnot.’ He hesitated once more, running a hand over his thinning hair. ‘Like I said, our number’s there in the folder. Call us if you need anything, anytime. We’re only five miles away, I can be here in a jiffy if there’s a problem.’

‘I’ll try not to disturb you if I can possibly help it. I’m pretty self-sufficient.’ She was not sure if this was actually true. It was a long time since she had put it to the test, but it was important that Mick should believe it. All she wanted now was to find the bed and fall face down on it.

‘Aye, well, that’s good. But we’re here if you need us. I mean it – anytime at all. Day or night.’ He said it more emphatically this time, and his gaze darted away to the top of the stairs. At the front door he turned back, holding it half open so that moths hurled themselves towards the light, wings whirring. ‘I’ll be back tomorrow at noon. I hope you have a comfortable night.’

‘I’m sure I will.’ She almost had to push him physically out of the door. She stood on the threshold, a narrow fan of light spilling through on to the step in front of her, determinedly waving him off so she could be sure he was finally gone. He raised his hand as he reversed the Land Rover with a scattering of gravel, but in the white cone of the security light his expression was anxious, just as it had been in the hallway.

When the sound of the engine had died away, Zoe leaned her back against the inside of the front door and allowed herself to slump to the floor.

He’s a new landlord, she told herself; he’s bound to be nervous the day his first tenant arrives. It was sweet, she supposed, how concerned he and Kaye were about her well-being, their little thoughtful touches. She hoped they would ease up once she’d settled in, though; she was troubled by the way they kept referring to her as their ‘guest’ rather than their tenant. She hoped they wouldn’t feel compelled to take her under their wing while she was here, save her from being lonely. Sometimes it was hard to make people understand how much you desired solitude. Or deserved it.

There was a telephone on a console table at the side of the entrance hall. She briefly considered calling home, but decided she was too tired, too fuzzy with whisky to deal with the conversation. She had texted Dan from the airport to say she had landed safely; she would call tomorrow. Instead she pulled herself to her feet, switched off the downstairs lights and climbed the stairs. On the first landing, to the right, she found her cases propping open the door to a lit room; inside, a master bedroom furnished neatly in crisp white, slate grey and duck-egg blue, with a small en suite leading off it. She threw her jacket over a chair, pulled off her biker boots in the bathroom doorway, bent her mouth to the tap and gulped down cold water, then collapsed on to the bed, where she fell asleep, fully clothed. Outside, the security lights snapped off and the McBride house was folded into the darkness once more.