Читать книгу Titan - Stephen Baxter - Страница 9

ОглавлениеFrom the air, Jiang Ling thought the Houston area looked like the surface of another planet, occupied and systematically bombed, perhaps, by malevolent aliens. The coastline was riddled with bays, canals, lakes, bayous and lagoons, all filled with oily water. A perceptible smog hovered over the glittering refineries around Galveston Bay.

Her NASA host pointed out Galveston Island, where she could make out a long, clear yellow slice of coastline: evidently a fine sandy beach, with what looked like a bulky oil rig, out to sea. The NASA person told her that the rig was there to dredge up sea-bottom sand, and pump it to the shore. The beach used to be stony, and the sand was only about eleven years old! Jiang was startled by the note of pride in the woman’s voice at this comical monument.

The plane – an ageing Cathay 747 – began its descent.

She was bustled off the plane and processed briskly through customs. The terminal building felt cool – chill, in fact. Jiang wore only a light jacket and trousers; she wished briefly she had brought something heavier. But when she emerged from the terminal building into the full strength of the July noontime Houston sun, the heat and humidity hit her as if she’d walked into a wall. The air was tangibly moist, the light intense, great polarized sheets of it bouncing into her eyes from the soft-looking asphalt surface, and the glinting metal carapaces of the cars which clustered here.

Waiting for her was a limousine, jet black, with a big softscreen panel, bearing a message which scrolled across the doors and wing. WELCOME JIANG LING, CHINA’s NUMBER ONE SPACEWOMAN. The message was repeated in Spanish, Chinese and English.

She clambered into the back of the limousine. It was like climbing through a long, padded corridor. There was a little drinks table, moulded into the upholstery, with champagne glasses and a decanter, and there were tiny TVs and softscreens. Waiting for her was a Chinese: Xu Shiyou, a senior Party official attached to the Embassy here, who would chaperon her. He was a fat man – American-diet fat, she thought – and his bald head was a round, sleek globe. Jiang was used to such meticulous planning and control; she was prepared to accept that she was a valued asset of the Party now, who required careful management.

It was a price she would pay, as she worked her way through these ceremonial duties, en route to space once more, some time in the imagined future.

The door was closed behind her, cocooning her in a little bubble of glass and new-smelling leather upholstery. The driver was sealed off by a partition; Jiang could only make out the back of the woman’s head.

The limousine pulled away. The windows of the car were clear, but Jiang became aware of a faint rippling effect, as the landscape slid past. The glass was thick, no doubt bullet-proof. She shivered, not just from the cold. Though she had circled the Earth in the Lei Feng Number One, she had never before travelled outside China. Now she wondered how she, as her country’s first space traveller, was going to be welcomed here in the home of Glenn and Armstrong.

The airport was on the northern outskirts of the Houston conurbation, and Jiang’s limousine, at the heart of a little cluster of cars, swept down the freeway towards downtown. The traffic was heavy, the smog thick in the air.

The land was hot, flat, the conurbation sprawling. The infrastructure – the layout of the roads – was clean and functional. And yet she had an impression – not of newness – but of middle age. Much of Houston’s growth, she knew, dated back to the space program growth period of the 1960s, and the oil boom of the 1970s. But those times were decades gone, and Houston was starting to age, to slump back into the plain.

Much of the time her view was obstructed by the roadside ads – huge, colourful, many of them animated – which battered at her senses, exploiting their slivers of competitive advantage. Most of the signs and ads were in Spanish.

There were water towers on the horizon, rusted, dominating. The land was greener than she had expected, but park-like, with orderly trees and thick-bladed grass; there seemed to be water sprinklers buried everywhere, many of them in full operation – even now at high noon, when much of the water would be wasted. Jiang looked at those glittering fountains, the shining green lawns, imagining the tons of water vapour being lost to the air each second, all over this baking city.

She remarked on this to Xu Shiyou. The contrast with the water shortages suffered in her own country was marked, she said severely. And it was a global problem: the growth in the population and the demands of the industrializing nations – including China – was poised to outstrip the planetary supply of fresh water which fell from the sky …

Xu smiled. ‘That is of course true,’ he said. ‘But until we can build pipelines to link the aquifers of Texas with the parched gardens of Beijing, there is little we can achieve by complaining about it.’

Jiang had the disquieting sense that Xu was mocking her.

‘You are nevertheless right in your perception,’ said Xu Shiyou, comfortingly. He waved a hand at Houston, beyond the car window. ‘America is a crass, empty-headed culture. And – look at that! – in the middle of this shower of advertising, you have their God, great neon crosses and beaming preachers, sold with the same methods as hamburgers.’

She looked out of the window anew. Xu was right, she saw; the ads for hair products and soft drinks and face implants were punctuated with immense crucifixes, images of Jesus.

‘Americans are free,’ Xu Shiyou murmured. ‘No intelligent person would deny that. But freedom is the minimum. I have lived and worked here for three years, and it is obvious to me that the Americans don’t understand the world beyond their borders – that they fear it, in fact.’ He looked through the window; animated electronic light glimmered in his eyes.

She stared out of the car as he lectured her. The office blocks of downtown Houston thrust out of the plain like a collection of launch gantries, grey in the mist and smog.

The Big S, JSC’s trophy Saturn V, was cordoned off from the public tours today and encased in scaffolding. Under Benacerraf’s instruction the bird was being surveyed, to see if it could indeed be made operational once more. But Marcus White had been asked to host the Chinese space girl, Jiang Ling, on her brief tour of JSC, and he couldn’t think of a better item to show her. So he got hold of a couple of hard hats and escorted Jiang inside the fenced-off rectangle that contained the booster.

Besides, he wanted to see the Big S for himself. He figured he may as well combine this makeweight ex-astronaut public relations chore with a little useful work.

The two of them walked along the three hundred and sixty feet of the fallen white-and-black-painted rocket, from its escape tower and Apollo capsule – both dummies – past the widening cylinders of the third and second stages, all the way to the gaping mouths of the five big F – 1 engines of the huge first stage. The Saturn V – AS – 514, built and ready to fly a late J-series Apollo mission to the Moon – was lying on its side, its stages and components separated. This was so the engines and other details of the mid-stages could be viewed, but it looked, White thought, as if the booster had shattered into cylindrical fragments on hitting the ground.

After three decades on the grass, the ageing of the Saturn was obvious. He could make out corrosion, cobwebs laced across the big wheeled A-frames which pinned the booster to the ground. The Stars and Stripes painted on the side of the second stage, the hydrogen-oxygen S-II, was washed out, with big red stripes of paint running down over the white hull. There was even lichen, growing on the fabric parts of the rocket engines.

They are not looking after this old lady well, he thought.

They weren’t alone in here; workers from JSC’s Plant Engineering Division were moving around the rocket, labouring through their detailed survey. One of them, attached to ropes like a mountaineer, was walking along the top of the big S-IC first stage, taking samples of the skin up there.

Jiang stood, slim and composed, looking up at the pressurization tanks of the second stage’s five J – 2 engines, big silver spheres which glowed in the diffuse Houston sunlight. She said, ‘It is beautiful.’ She smiled.

‘Yeah,’ White growled. ‘But the damn space program was more than a series of photo-calls.’

‘Was it?’ Jiang looked sad. ‘But this creature, General White, is a dream of the 1950s. So crude! – a painted monster of rivets and bolts and gloss paint –’

‘To me,’ White said, ‘it’s not rivets and bolts and paint. This baby was designed to fly to the Moon. But it’s having a tough time fulfilling the mission we finally gave it: lying for four decades horizontally, in the Houston climate.’

There was an access hatch open near the top of the second stage, the S-II. Jiang and White took turns peering in.

‘You know,’ White said, ‘when they first opened this up – for the first time in fifteen years – they found little skeletons, mice and small birds, a foot deep. And the base of the stage was coated in guano, from pigeons and owls, islands of it in lakes of moisture trapped in there. After all, the drainage of this damn thing was designed to be end to end, not side to side.’

‘They made no effort to protect it from such erosion?’

‘Oh, sure,’ White said. ‘All the openings large enough to allow in birds were covered with screens; there were ventilation openings knocked in the hull … but none of that is going to work, if you neglect the upkeep for long enough. They did try coating the second stage with polyurethane foam for insulation. But the sunlight takes its toll. All the uv we get these days. There are whole chunks of the insulation missing, great big pock marks … If you went up to the top of the S-II, you’d think you were walking on the surface of the Moon. Even the paint work isn’t authentic. They use big decals, as if it was a Revell kit, to fake up the lettering and the flags. How about that. It’s like spray-painting the Sistine Chapel. This poor old lady is going to require one hell of a refurbishment project.’

Jiang looked at him sharply. ‘Refurbishment?’

White knew he shouldn’t say any more. But there was no point in living seven decades and flying to the Moon and back if you couldn’t shoot your mouth off to a young girl once in a while. So he said, ‘Sure. You know, manufacturing has come on a long way since the Saturns were put together. CAD/CAM techniques, total quality programs, composites and aluminum-lithium alloys that are a lot lighter and stronger than this old aluminum shit … If we were to rebuild this bird, we could upgrade her performance a hell of a way.’

Jiang laughed, but not unkindly. ‘Perhaps. It is a fine dream. Certainly I sense how angry you are at this, the condition of your “big S”.’

‘I guess the bad guys did a pretty good job of killing off this old lady after all. All they had to do was let her lie here and rust. And they even got to show her off as their capture.’

Jiang grimaced. ‘Like a trophy from a hunt. Yes; humans are rarely logical, even within a space program. But it could have been worse. At least the remaining Saturn hardware is honoured as a relic of a great triumph.’

White ran his hand along the corroded hull of AS – 514. ‘A relic,’ he repeated.

This kid seemed to understand. She’d picked the right word. Relic. Maybe. But not for much longer.

His anger dissipated as he thought about that. The technicians crawling over the rocket were busy, competent, bustling. They nodded to White, smiled at the girl.

Okay, there had been some savage mistakes in the past, and this poor broken bird was a symbol of them. And maybe NASA was never going to be the same again; maybe it even deserved to be bust up and subsumed into Agriculture or whatever. But he had the feeling that the old days were coming back, just once more, as it had been working on Apollo, when everyone worked a hundred and ten per cent and the colour of your carpet didn’t matter so much as what you knew and what you could do. For just a short time, maybe NASA was going to pull together again, to achieve the Titan mission, to achieve one more moment of greatness.

If it came off, it would be a hell of a thing.

The Houston Coliseum was a huge underground arena that reminded Jake Hadamard of nothing so much as a gigantic, hollowed-out car park. Today, the roof was hung with cute little models of the Lei Feng Number One spaceship. The air-conditioning, he thought, was typically Texan, which is to say the whole place was so chill you could have stored corpses in here. As they waited for the Chinese party, everybody seemed to be standing up, and Hadamard found himself shivering in his suit jacket.

There were hundreds of people here, standing in rows: bands, police and firemen and National Guard in neat ranks, politicians and industrialists in open-topped convertibles. And Hadamard himself had brought a little party of senior NASA people: Marcus White, Paula Benacerraf and her family, some of the managers from JSC.

On a stage at one end of the arena stood Xavier T. Maclachlan, the ambitious Texas Congressman who had engineered the event. He was a thin, jug-eared man of about fifty. Now he whooped noisily into a microphone, and waved his big ten-gallon hat in the air, and gladhanded his guests.

Hadamard, bored and cold, checked his watch; there were still some minutes to endure before the Chinese spacewoman arrived.

Al Hartle came bearing down on him, resplendent in his Brigadier General’s uniform. He was clutching a full tumbler of bourbon. Hartle was a power in the USAF Space Command; Hadamard had encountered him in briefings for the Cabinet. ‘This is some display,’ Hartle said. ‘Some fucking display.’

Hadamard was amused; Hartle was upright and rigid, his head like a steel cylinder jutting up from his great box of a body. But he was clearly a little drunk, and anger seemed to be seething inside him, hot and deliquescent, like a pupa within its rigid chrysalis.

He prompted, ‘You think so?’

‘In 1961 we sent John Glenn on a fucking world tour. Now we’re on the receiving end of the tours, and we have to kowtow to some damn Red Chinese.’

‘Well, they have made it to orbit, Al.’

‘For the same reasons we did,’ Hartle growled. ‘Geopolitics. Just to prove their balls are as big as ours.’

‘Space as the symbolic arena. Well, I guess you’re right. But they hardly need symbols, Al. China’s GDP passed ours years ago.’

‘I know. That, and this woman in orbit, and this damn Shuttle crash, have sent us all into a fucking panic. I tell you, it’s like Sputnik all over again. And look what came out of the dumb decisions that were made when Sputnik went up. Apollo. Holy shit. A disaster that has reverberated for fifty years.’ He eyed Hadamard. ‘So you still throwing money down the john for another Shuttle?’

Hadamard laughed. ‘I’ll tell you all about it when you tell me about your Black Horse program, Al.’

Hartle grunted, and took a deep slug of his bourbon. ‘And your space cadets haven’t responded to our L5 proposal yet.’

The L5 proposal was the Air Force’s official recommendation on what to do with the left-over Shuttle and Station technology. The Station should be completed, and converted to a surveillance station – maybe even some kind of weapons-bearing battle station – and towed out to L5, the stable Lagrangian point two hundred and forty thousand miles from Earth, at the third corner of a triangle including Earth and Moon.

Hartle stabbed a finger at Hadamard’s chest. ‘You heard the case. It’s the new heartland of space. Circumterrestrial space encapsulates Earth to an altitude of fifty thousand miles. Who rules circumterrestrial space commands Earth; who rules the Moon commands circumterrestrial space; who rules L4 and L5 commands the Earth-Moon system.’

Hadamard sipped his drink. ‘Maybe you’re right, Al. But –’

‘The Red Chinese,’ Hartle hissed. ‘The Red Chinese. Those bastards think this is going to be their century. They’re making expansionist noises all over, impacting ten countries, from Taiwan to Russian East Asia to the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea … Christ, even the Australians are worried.’

Hadamard murmured, ‘Is it really so bad? Our weaponry is still so far ahead of theirs that we can contain them for a long time to come. And –’

But Hartle wasn’t listening. ‘If we don’t take Lagrange soon, we’ll find the damn Red Chinese up there waiting for us. And then we’ll have lost, Hadamard. We’ll be paying tribute to the bastards for the rest of time. Just like the days of the Qing Dynasty. Read your history, boy.’ He approached Hadamard, and thrust forward his hawk-like face, weathered by altitude and desert sun, and that inner anger burst to the surface. ‘Listen to me,’ he said, his voice a thick rasp. ‘I know some of those assholes in the NASA centers are putting forward dumb-ass schemes about leveraging this Chinese-in-space stuff into some big new Flash Gordon adventure in space. They want to start the whole damn thing over again. But that’s bullshit. You hear me? You try to fly any such damn thing and we will shoot you down, boy.’

He backed off, fixing Hadamard with a final glare, and stalked off into the crowd.

Good grief, Hadamard thought. He found himself trembling. He took a slug of his own drink, to regain his composure.

What anger. But we’re not at war, he thought, cowed by Hartle’s intensity. For all his political antennae, he couldn’t tell if Hartle’s anger was representative of the thinking inside the closed doors of the military, or if Hartle was some kind of ageing maverick, frustrated because he was unable to get his case accepted.

In fact Hadamard still had to make his decision, about disposing of the Shuttle assets.

Nobody wanted to go back to a regular flight schedule with the three remaining orbiters – the cumulative risk was just unacceptable – but some kind of one-off mission was still plausible, politically. And besides, he was still waiting for Benacerraf’s recommendation.

Anyhow, Hartle was threatening the wrong guy. Hadamard was no space buff. He was interested, he told himself, solely in managing budgets; if NASA never flew more than another July 4 skyrocket he could care less.

… But, oddly, against his expectations, he found himself leaning more towards proposals like the ones coming out of Marshall, about fantastic jaunts to the Moon or Mars or Venus, rather than building some monstrous Buck Rogers space battle station in the sky.

He couldn’t get the image of the crashing orbiter out of his head, the idea of the grizzled old Moonwalker at the controls to the last.

He found Paula Benacerraf, who was here with her daughter, and a kid: a boy, who looked bored and restless. Maybe he needed a pee, Hadamard thought sourly. On the daughter’s cheek was an image-tattoo that was tuned to black; on her colourless dress she wore a simple, old-fashioned button-badge that said, mysteriously, ‘NED’.

Hadamard grunted. ‘I’ve seen a few of those blacked-out tattoos. I thought it was some kind of comms problem –’

Jackie Benacerraf shook her head. ‘It’s a mute protest.’

‘At what?’

‘At shutting down the net.’

‘Oh. Right.’ Oh, Christ, he thought. She was talking about the Communications Decency Act, which had been extended during the winter. With a flurry of publicity about paedophiles and neo-Nazis and bomb-makers, the police had shut down and prosecuted any net service provider who could be shown to have passed on any of the material that fell outside the provisions of the Act. And that was almost all of them.

‘I was never much of a net user,’ Hadamard admitted.

‘Just to get you up to date,’ Jackie Benacerraf said sourly, ‘we now have one licensed service provider, which is Disney-Coke, and all net access software has built-in censorship filters. We’re just like China now, where everything goes through the official news agency, Xinhua; that poor space kid must feel right at home.’

Benacerraf raised an eyebrow at him. ‘She’s a journalist. Jackie takes these things seriously.’

Jackie scowled. ‘Wouldn’t you, if your career had just been fucked over?’

Hadamard shrugged; he didn’t have strong opinions.

The comprehensive net shutdown had been necessary because the tech-heads who loved all that stuff had proven too damn smart at getting around any reasonable restriction put in place. Like putting encoded messages of race-hate and smut into graphics files, for instance: that had meant banning all graphics and sound files, and the World Wide Web had just withered. He knew there had been some squealing among genuine discussion groups on the net, and academics and researchers who suddenly found their access to online libraries shut down, and businesses who were no longer allowed to send secure encrypted messages, and … But screw it. To Hadamard, the net had been just a big conduit of bullshit; everyone was better off without it.

Jackie was still droning on, in the sanctimonious way that might have been patented by serious young people. ‘This is the greatest reverse in free access to information since Gutenberg. The net was never meant to be sanitized and controlled. The shutdown will hit technological development, education, jobs …’

Hadamard was quickly bored. His glance was caught again by Jackie’s button-badge – which sat, he couldn’t help notice, over her breast, which was small and firm. Her little boy clung to her leg.

‘NED. Who’s that, a rock star?’

‘New Luddites,’ Paula Benacerraf said.

‘Oh. I heard of them.’

‘Believe me, Jake, you don’t want to get into that either.’

Maybe I do, Hadamard thought.

He knew Xavier Maclachlan had picked up on some of what the Luddites were arguing for. The Luddites had attracted a broad band of the younger generations who responded to a core anti-science message with, it seemed to Hadamard, their guts, not their heads. And that gut response was what Maclachlan was tapping into.

In his heart, Hadamard was uncomfortable with Maclachlan: his protectionism, his fundamentalist Christianity. But Hadamard had to concede that Maclachlan was hitting popular nerves among the electorate. It was, he thought, entirely possible that Maclachlan would indeed become the next President, just as the polls said. And if that happened, Jake Hadamard would be going to him for a new job.

Maybe I do need to figure out what’s going on inside the head of the likes of Jackie Benacerraf, he thought.

Benacerraf said, ‘Speaking of Luddites, I hear we lost the Mars sample-return mission.’

‘Yeah.’ Now, there was a pisser, even for a space cynic like Hadamard. ‘You know how they stopped it in the end? We had to apply to register the returned Mars samples with the Department of Agriculture in the state we planned to land. Just in case there was life aboard, like in that meteorite a few years ago. But you could crashland anywhere, so we were forced to apply in every state in the Union. And then we had to start applying for similar permits abroad. All that damn paperwork, the legal tangles. And when the first refusal came in, that was pretty much it.’

Benacerraf shook her head. ‘So we lost another fine mission, and any chance of confirming the biological stuff from the meteorite. Damn, damn. Once, we sent spacecraft to Jupiter, the rings of Saturn, out of the Solar System altogether. Now, we’re too scared to bring home a handful of Martian dust … You know, our attitudes don’t seem to be shaped by the rational any more.’

Hadamard shrugged. ‘It was predictable. The slightest suggestion of bugs from Mars was always going to raise a panic. It’s the times we live in.’

But now Jackie started in again, arguing with her mother.

Hadamard tuned out. He was still bored and cold, and he was getting no closer to Maclachlan like this. He made his excuses and moved on, abandoning Benacerraf to her dysfunctional family.

Up on the stage, Maclachlan started making a short, crass speech of welcome; evidently the Chinese party was on its way.

It seemed to Hadamard that Maclachlan was working his audience here almost greedily, as he stared into the camera lights. It was ironic that Maclachlan, the great protectionist and anti-space campaigner, was here to welcome a spacegirl from China. But it was politics. Maclachlan was turning this event, like everything else he touched, into just another part of his populist build-up towards what everyone expected would be a winning bid for the Republican nomination for the White House in 2008.

Hadamard glanced around the crowd, sizing up who was here, figuring how he could get to maximize his own contact time with Maclachlan.

There were ragged cheers. Hadamard turned. The Chinese party was arriving in their hard-top limos, rolling smoothly down the ramp from the overground. Led by Maclachlan, the waiting hundreds broke into noisy applause.

The limos did a brief turn around the Coliseum floor. Before stopping at Maclachlan’s feet the cars came close to Hadamard; he found himself looking into the pretty, oval face of Jiang Ling, from no more than ten feet. She looked young, he thought, and scared. As she had every right to be.

When she got out of the car, accompanied by some fat Chinese official, she turned out to be slim, about thirty-five, delicate-looking in what looked like a peach-coloured Chairman Mao jumpsuit with a neat little jacket over the top. She climbed the few steps up to meet Maclachlan, who grabbed her possessively and stuck his ten-gallon on her head.

Hadamard tried to imagine this fragile girl being launched into space, in the mouth of one of those huge, unreliable, 1950s-style Chinese boosters. Not for the first time the idea of spaceflight seemed monstrous to him: like a human sacrifice, to serve geopolitical ends.

But, he thought ruefully, as the head of the Agency which had just crashed a Space Shuttle he had no grounds for complacency.

Maclachlan, holding onto Jiang, finished up with a Chinese phrase, clumsily delivered. ‘Ni chifanie meiyou?’ Jiang looked disconcerted; Maclachlan laughed and hugged her anew. ‘I said to her, “Have you eaten yet”? Exactly what I’d be asked if I visited your home. Right, Ji-ang?’ The slim Chinese girl smiled nervously. ‘Well, you sure as hell will eat fine here in our home – Texas-style! Enjoy, folks!’ He whooped, the amplified noise ear-splitting.

And now the covers were taken off ten big barbecue pits, set up in the middle of the arena, and suddenly the air was full of the rich, cloying stink of burned cattle flesh. There was an eruption of applause. The girl astronaut looked utterly bewildered.

Maclachlan, holding tight onto his human Sputnik, clambered down off the platform and began to work his way through the crowd. Hadamard stepped forward, discreetly, towards the platform.

A year after the crash, Benacerraf’s daughter, Jackie, came to stay for a couple of days. She brought her two children, Ben and Fred, four and five respectively. The boys seemed to fill Benacerraf’s ranch house at Clear Lake with light and noise, and she spent as much time as she could with them. She got into a routine of working through the day at JSC, spending the early evenings with the children, and staying up nights to work on drafts of her recommendation to Hadamard.

One night, Jackie disturbed her. She came padding barefoot across the kitchen floor to where Benacerraf sat with her softscreen spread out over the big walnut dining table, at the center of a pool of scattered notes and documents.

‘Mom, you must be crazy,’ Jackie said gently. She went to the refrigerator, and returned with glasses of apple juice. ‘Do you know what time it is? Three a.m.’

‘So it is,’ Benacerraf said. ‘I don’t know where the time goes.’ She rubbed her face; the balls of her eyes felt gritty, the muscles aching and sore.

Jackie sat at the table. ‘So how long has this been going on?’

‘Oh. Ten, eleven months or so.’

‘Ten months? My God, Mother.’

‘It isn’t so bad. I travel a lot; I catnap on flights or in the car. And there’s an end in sight. I’m working on a project. When it’s done I’ll be able to rest.’

‘Mom, you’re not as young as you were.’

Benacerraf sighed. ‘I guess it’s a daughter’s job to say things like that. Well, neither are you.’

‘But I know it. And you won’t catch me working like that.’ Jackie smiled, vaguely. ‘Life’s too short, Mom. After all, what job is worth wrecking your health for? Seriously, you shouldn’t let them push you so hard.’

Benacerraf reached behind to rub the muscles at the back of her neck. ‘There is no “them”. Or I’m part of “them”. I’m a senior official in the national space program. I have to try to make things happen. Besides, what doesn’t seem to occur to you is that maybe this work makes me happy.’

‘If that’s so, why are you so prickly?’

‘I’m not prickly, damn it –’ Benacerraf subsided, and Jackie grinned at her.

It was a familiar argument to Benacerraf. What is it with you young people? What in hell happened to the work ethnic? Don’t you take anything seriously? …

It was a long time since Jackie had tried to push ahead with her journalism. At times Benacerraf felt she couldn’t stand to see Jackie drift through her life like this, like so many of her age group, floating from one career option to another, passing through relationships that coalesced briefly – sometimes leaving behind kids, as had Jackie’s brief marriage – and on to the next vague destination.

It wasn’t the structure of Jackie’s life that bugged her, but her casualness, her lack of seriousness. There seemed no need to struggle, to take responsibility – no attempt to build things.

She suppressed the impulse to snap. Now, of all times, wasn’t the moment to pick a fight with her daughter.

Anyhow, she thought, maybe Jackie and her generation are right. Look at me, slaving here in the small hours, over this huge Titan boondoggle. Maybe my day is done. Maybe this project is the last spasm of whatever drove us, in the last century, to our great, ambitious endeavours. Perhaps when this is over – when my generation has gone, the last great rocket ships fired off – the world will sink back, lapse into a kind of high-tech pastoralism.

Jackie got up and walked to Benacerraf’s back, and took over rubbing her neck muscles for her.

‘That feels good,’ Benacerraf said.

‘Just like when I was a little girl, huh?’

‘Even then you always had good hands.’

‘All that tennis I played.’

‘You could have been a surgeon. A physiotherapist –’

Jackie laughed. ‘A carpenter, like Jesus. Come on, Mom; you’re sounding like a cliche again.’

‘Sorry.’

Jackie pointed to the softscreen, which Benacerraf had folded over. ‘You going to tell me what you’re working on?’

I’m not supposed to, Benacerraf thought. But you deserve to know.

‘Here.’ She unfolded the softscreen and smoothed out its creases.

Jackie sat down again, pulled the softscreen to her, and ran her finger over its smooth fabric surface, a reading habit she’d developed as a child.

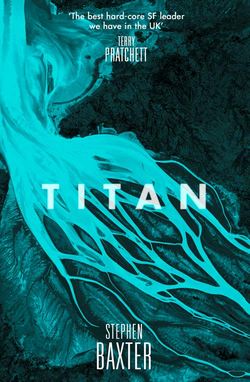

… The purpose of this memorandum is to obtain your approval to use Space Shuttle and ancillary technology to fly an open-ended manned mission to Saturn’s Moon, Titan, in the short-term timeframe, with a resupply and retrieval strategy in the medium-term based on new-generation Reusable Launch Vehicle technology.

My recommendation is based on an exhaustive review of pertinent technical and operational factors and also careful consideration of the impact that either a success or a failure in this mission will have on the future of the Agency.

My objective has been to bring into meaningful perspective the trade-offs between total program risk and gain. As you know, this assessment process is inherently judgemental in nature. Many factors have been considered during a comprehensive series of reviews, conducted over the past several months, to examine in detail all facets of the considerations involved in planning for and providing a capability to fly a crew of five or six on a Titan landing mission. A key benefit for the Agency is the motivation such a mission provides for maintaining funding and commitment for the upcoming RLV program.

In conclusion, but with the proviso that all open work against the open-ended Titan mission is completed and certified, I request your approval to proceed with the implementation plan required to support an early launch readiness date.

Turning to details of the –

Jackie pushed the softscreen back across the table to her mother. ‘You can’t be serious,’ she said.

Benacerraf sipped her apple juice. ‘Never more so.’

‘Is this to do with all that JPL shit? My God, the arrogance. You can’t even fly to orbit and back without crashing all over the place. How do you imagine you can send people to Saturn?’

Benacerraf shrugged. ‘Do you really care? You’ll learn all about it when it gets made public, if you’re interested.’ As, she thought sourly, you probably won’t be.

But Jackie was staring at her. ‘Oh. Hold up. Hold it right there. I think I’m just starting to figure this out.’

‘Jackie, I –’

‘You want to go. Don’t you? To Titan, on this ridiculous one-way jaunt.’ She slammed the table. ‘Mother, you are not going to Saturn.’

Benacerraf was taken aback by her anger. ‘Jackie –’

‘Don’t you know what it’s like for me, when you fly in space, in that ludicrous old technology? Every moment you were off the ground in Columbia, I could think of nothing but the danger. And when Columbia went through the crash, I was convinced I wouldn’t see you again. Right now the kids are too young to understand, but soon … And now you talk about this, about leaving the Earth altogether?’

‘It isn’t like that. There’s a retrieval strategy, based on –’

‘You don’t understand, do you?’ Jackie’s eyes were dry, her expression hard. ‘Listen to me. Flying into space is meaningless. It always was. The technology is antiquated and unsafe, and there’s nowhere to go, and all your language of risk reduction is just a play with words. And for what? The whole thing is just a selfish stunt.’

Benacerraf felt her own anger building in response. ‘I won’t be called selfish by you. I’m more than just your mother, damn it. I’ve raised you, as best I could. And now you’re grown, my life is my own –’

Jackie snapped, ‘Why don’t you put that in your report?’ She walked out of the kitchen.

Benacerraf sat for long minutes.

Then she pulled the softscreen towards her.

Hadamard hauled on the thermal meteoroid garment. It was a heavy, floppy, deflated balloon made of tough white Beta-cloth. There were sockets over the front, where he plugged in his backpack umbilicals for oxygen, water and telecommunications.

Alongside him, Buzz Aldrin – thirty-nine years old, bald as a coot, and eager as a virgin – was climbing into his own suit.

The Moon suit, authentically rendered, was unbelievably primitive, Hadamard reflected. To think you actually had to assemble it, here on the lunar surface. It was incredible none of the Moonwalkers had been killed, betrayed by leaky plumbing.

When his suit was closed Hadamard flicked a switch, and the pumps and fans in his backpack started. He heard the hum of machinery, and oxygen whooshed across his face.

The veracity of the experience was extraordinary, right down to the sensation of increasing pressure in his ears.

He gave Aldrin a thumbs-up, and through his shining bubble helmet, Aldrin grinned back at him.

The first line in the script was Hadamard’s.

‘Houston, this is Tranquillity. We’re standing by for a go for cabin depress, over.’

Tranquillity Base, this is Houston. You are go for cabin depressurize, over.

Aldrin opened the valve that would vent Eagle’s oxygen to space. The pressure crept downwards, much more slowly than Hadamard had expected, despite his detailed knowledge of the timeline. It took all of three minutes to get down to four-tenths of a pound.

‘Everything is go here,’ Hadamard said. ‘We’re just waiting for the cabin pressure to bleed, to blow enough pressure to open the hatch …’ Hadamard could hear a stiffness in his own tone, as he pronounced the scripted words.

The events of the Moonwalk – at any rate the few minutes surrounding the first footstep itself – had become utterly familiar, through a thousand reproductions and adaptations and digitizations and dramatizations; it was thought that a copy of this script resided in every home with online access, which meant most of mainland US. The rest of Apollo – the later flights, even the rest of the Apollo II mission – had been largely forgotten now. But, Hadamard thought, the story of these few minutes of the first footstep was probably as familiar, in the public mind, as the story of the Nativity.

It was one hell of a legacy to manage.

‘Let me see if it will open now,’ Aldrin said. Clumsily, he reached down for the hatch handle. He tugged on the thin metal door, but it stayed firmly shut. Aldrin pulled vigorously, and Hadamard feared he might rip the thin metal shell of the Lunar Module. Finally Aldrin peeled back one corner of the door to break the seal.

The next part of the litany was Hadamard’s. ‘The hatch is coming open,’ he said, and he heard, spontaneously, excitement creep into his voice.

As if it were all real.

A flurry of ice particles gushed out into the lunar vacuum beyond the hatch, the last of the LM’s atmosphere.

Aldrin held the hatch open, and Hadamard sank to his knees and carefully moved his suited bulk backwards through the opening. It was awkward, confining, more like struggling to escape from the neck of a sack than leaving an aircraft.

The Aldrin simulation gave him running guidance. ‘Jake, you’re lined up nicely. Towards me a little bit. Okay, down. Roll to the left. Put your left foot to the right a little bit. You’re doing fine …’

Hadamard crawled out onto a large platform called the porch, which bridged the gap between the hatch and the ladder to the surface. He groped backwards with his boots, and found the top rung. He got hold of the porch’s handrails and raised himself upright, cautiously.

‘Okay, Houston, I’m on the porch.’

Before him was the blocky, shadowed bulk of the LM. Beyond that, reaching all the way to the close horizon, was a pocked, rock-strewn, tan brown surface. There were craters everywhere, of all sizes, right down to the little micrometeorite pits on the sides of the rocks that the astronauts had called zap pits. On some of the rocks he saw an exotic sparkle, like a glaze. The colours, though, depended on which way he looked, on the angle to the sun, as if he was looking through a polarizing filter.

He knew this representation had been beefed up from the original photographs with fractal technology. Those zap pits weren’t real, for instance. But it looked pretty convincing to Hadamard. He could well believe this place had been gardened, pulverized by meteorite strikes, for billions of years.

The land, he saw, actually curved, gently but noticeably, all the way to the horizon, and in every direction from him. He was standing on a rocky sphere, no more and no less. This was a small world indeed. The sky was utterly dark, save for the blue Earth, which was almost directly overhead, visible only if he tilted back his head …

‘What do you think of it?’

He turned. An astronaut had come bounding around the far side of the LM, her suit glowing white.

‘Paula?’

‘Hi, Jake.’

He felt an odd reluctance to come out of the illusion. ‘Disney-Coke have done a good job.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Maybe this was what it was all about in the first place, do you think? Circus stunts, entertainment? And maybe in a few more years these visitors’ centers will be all that’s left …’

‘Oh, how symbolic. And that’s why you’ve dragged me here today, Paula. Correct?’

‘Did you read my recommendation?’

‘Not past the management summary. No.’