Читать книгу Summer of Fifty-Seven - Stephen C. Joseph - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

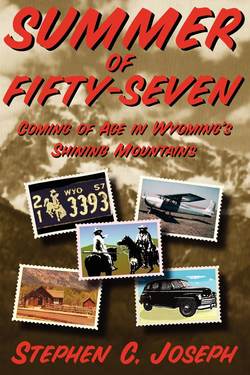

FROM BOSTON TO MOOSE JUNCTION

ОглавлениеIt was merely a few months past my nineteenth birthday, during the late winter of 1956-1957, when I decided to ride my thumb to Alaska, four thousand miles and more.

Who knows how, or where, such desires take root, from what long-hidden seeds they sprout. Are they stirred in from the genetic soup of grandparents who left the Old World for the New? Are they remembered from whispered words of stories or lullabies heard near the dawn of life? Are they lessons learned in school and at the movies, of Boone and Crockett, of Huck Finn, and, later, of Shane?

I have a scratchy eight millimeter old home movie film: the family at a picnic in the woods of the lower Hudson Valley. All, except one, are gathered around the wooden table. Then, out from among the trees, knobby knees striding under short pants, a crude walking stick waving, comes three-year-old me, unmistakable joy on my face and in my heart. If I had been old enough, I undoubtedly would have been whistling. Could I have known then that the archetypal American myth is that of the lone wanderer, the one who rides in and then rides on, looking always only for the next mountain, and again and again pushed over the hill and far away by the sight of a neighbor’s chimney smoke? Call me Ishmael?

Later, in early adolescence, it was Western dime novels (though they indeed cost twenty-five, and sometimes thirty-five cents even in those long-ago days). In compulsive ritual, every Friday after school I would pedal my bike the three miles to a favored cigar store, spend what seemed like hours choosing from among the books on the racks, and pedal home again. What fantasies galloped along with that two-wheeled and many-spoked magic steed, pushing across the suburban prairie, carrying the precious mail by Pony Express! Once home, I would read the week’s treasure as slowly as possible, making it last, obsessively, until the next Friday. With Max Brand, Evan Evans, Peter Field, Luke Short, and a score of other authors, I stole horses from around Kiowa campfires, drove long-horned, half-wild cattle across the Cimarron, rescued the widow’s ranch from the banker who wore the black string tie, held out against all odds at Fort Apache, and most, most of all, lived as a Free Trapper in the 1830s Shining Mountains.

With the zany compulsiveness of adolescence, I held my treasures in a special, separate bookcase, arranged alphabetically by author, nested within unique sections by publisher: Pocket Books, Signet Books, Bantam Books, and the new, ‘expensive’ Ballantines. Dreams were filled with the contents of that bookcase. The Black Hills, the Arizona Territory, Texas to Wyoming, the endless grass of Montana, and, striding north to south across my paradise, what we call the Rockies, and what the earliest white men who saw them called the Shining Mountains. At school, I drew maps, both accurate and fictional ones, of that country of the heart, hiding my work behind a bent head close to a propped-up schoolbook. I memorized the illustrations in the Encyclopedia Britannica that chronicled the westward march of Manifest Destiny.

I roamed, with my Daisy Red Ryder Carbine BB-gun, the shrinking woods and weeded lots of my suburban town, shooting (I blush to say) robins and squirrels, seeing in my mind’s eye the tall grass prairie and the bison, the mountain forests and the elk. By twelve or thirteen, I had prevailed upon my father to purchase for me three antiques: a 45 caliber Sharps buffalo gun, an 1874 Springfield military carbine, and an old Stevens pump 22. All were non-functional, at least to everyone but me. They rested in a rack on my bedroom wall, and every night, just before sleep, I would take them down one by one, check that they were cleaned and oiled (they always were), and aim them at the invisible targets of my imagination: loaded, cocked, sighted-in, and trigger-pulled.

In my nineteenth year I was a sophomore at an excellent college: a “grind” pre-med in a decade when the one phrase defined the other. I was a pretty good, and very aggressive, athlete, an A-student with little fundamental comprehension of the relevance and significance of what I was learning, and, not by choice, a virgin (my knowledge of detailed female anatomy and physiology mostly gleaned from what was then known as “heavy petting” and, upon rare occasions, reciprocal digital stimulation).

Most importantly, I felt the world closing in upon me, rather than opening out before me. I could see a clear road ahead, but narrowing, narrowing. As has perhaps been true forever for young males who don’t quite feel that they fit, I yearned to break free, to measure myself by my own, rather than others’, benchmarks, to seek a frontier not yet closed.

I spent hours haunting the library of the Anthropology Department, voraciously reading the accounts of the early students of the Plains Indians, of the Northwest Coast, of the Arctic peoples. And then, one wet, cold Boston March afternoon, I came upon a hand-written 3x5 file card tacked to the library bulletin board:

“Wanted: Riders to share expenses and driving to California.

Leave early June. Call Gene at 824-9787.”

So, perhaps, riding with Gene part-way to California wouldn’t exactly be crossing the Cumberland Gap with Boone, but it could be a first leg to Alaska.

Alaska seemed to me to be what was left of all I had dreamed of. It was expected that Alaskan statehood would take place in either 1958 or 1959, truly closing the American frontier. If I could get there before that fact, while it was still the Alaska Territory, I could have a taste of what my heroes had felt in the Dakota Territory, in Montana in the early days, in Arizona and New Mexico before 1912. If not, it might be all gone, forever, and something might also go out of my young life with it, something I would never know, but always regret the absence of.

And so, in the second week of June, Gene, Allan, and I piled into a creaky Chevy, and pulled out of Cambridge, headed, as the best dreams on this continent have always been directed, West. My plan was to ride the Lincoln Highway with them as far as Rock Springs, Wyoming, there to leave them and then strike out alone north through Yellowstone to Montana, and up across the Canadian border to the Alaskan Highway. That road was scarcely 15 years old, four years younger than myself, pushed through the muskeg and mountains as the AlCan Highway by military engineers, to forge a land route from the Lower 48 to Alaska, and thus to pre-empt a possible Japanese invasion through the Aleutian Islands. The Road West, and the Road North, were fused in my mind.

Family and friends were aghast. But knowing my stubbornness and eccentricities, no one raised much of a fuss; my folks kissed me good-bye over the phone, and my friends just shook their heads.

After much thought, and some experimentation, here is what I took with me. On my back (below a 1950s ‘crew-cut’ so short as to preclude the need for repetition by a licensed barber for some time to come): a short denim Wrangler jacket, the one with the metal buttons, washed soft and supple. A cotton work shirt. A nondescript Bulova watch with leather band. Denim jeans (we called them “dungarees” or “Levi’s” then, and you never, ever, turned up the cuffs unless you were a girl, or a city guy). Cotton ‘sweat socks’, and a pair of poorly broken-in Red Wing work boots. A broad plain leather belt, from which hung a four-inch leather case enclosing a bone-handled pocket knife with four blades: long and short cutting, a slot screwdriver/bottle-opener, and an awl. No hat, no sunglasses, both of which were then considered to be affectations.

In my hand: a weathered Gladstone bag, the kind that opens from a top zipper to offer broad and square access. Inside the bag: three extra shirts (one a warm flannel), three ‘T-shirts’, all the same plain white (no funny illustrations or double-entendre slogans, no designer logos in those days), three pairs of Jockey shorts (the fourth I wore under my Levi’s), the other three pairs of sweat socks, two extra handkerchiefs and a red-checked bandanna, a spare pair of Levi’s, a pair of white Converse ‘Hi-Top’ sneakers, a shaving kit (toothbrush and paste, a Gillette ‘safety’ razor and packet of individually-wrapped double-edged ‘Blueblades’, a small plastic soap case for washing and shaving, a travel shaving brush, a small metal mirror, and a few Band-Aids), a hand towel, a half-roll of toilet paper crushed flat, wooden kitchen ‘Strike Anywhere’ matches and a small candle, a small flashlight with the old grey, blue, and red ‘Every Ready’ batteries, and a hundred feet of parachute cord.

Strapped to the top of the Gladstone, between its handles: a light cotton sleeping bag, protectively wrapped inside a rubberized Army surplus rain poncho.

In my pockets: no keys at all—surely the sign of the liberated road traveler. A wallet with my identification (including my draft card), pictures of my mom and dad, brother, and dog, and a rolled-up condom. The latter had rested hopefully, but unsuccessfully, in the wallet for so long it had created a permanent circled ridge in the leather; Planned Parenthood should be grateful that I, like many American boys, never got the chance to use that particular dried and aged device. But I was ever hopeful, and, as the Tom Lehrer song of that era advised, was prepared to “Be Prepared.” I had about one hundred and twenty dollars, some in my wallet, some in the Gladstone, and the majority tucked in a plastic bag under the sole of my left foot in the Red Wing boots.

Gene and Allan were neither scintillating nor sympathetic companions, being graduate students at the Business School, and thus intolerant of both my callowness and my adventuresome idealism. But I was a full-share paying passenger, didn’t fill the Chevy with heavy luggage, and thus was, in their view, a reasonable cost/benefit addition. We didn’t talk much, the radio filling the silence with Chubby Checkers, Fats Domino, and The King. The miles rolled by: Boston down through old Routes 16 and 30 to Connecticut and the Wilbur Cross Parkway, through Hartford where the gas wars always allowed you to fill up at an economical thirty-two cents per gallon, into the New York suburbs and across the George Washington bridge, struggling down the Jersey Turnpike until we reached the old Pennsy Turnpike, one of the country’s earliest-built, controlled-access, long-distance roads.

Somewhere in western Pennsylvania, we stopped for the first night. Gene and Allan looked for a motel in the farm town along the pike, but I was counting dollars for the miles ahead, and determined to lie up in the woods, where they would retrieve me the following morning. I rolled my bag out in a low and sheltered spot as dusk approached, lulled by the sound of a distant tractor, using the last of the Daylight Savings Time light to cultivate a few more rows. Soon the closer-in whine of mosquitoes drowned out the tractor, and I was faced with an uncomfortable choice, one that would often recur that summer. You either put the rubberized poncho over your face, neck, and hands, and sweltered, or hunched over as close as you could at the top of the short bag, and bled. Alaska seemed very far away, and I felt very small and alone.

Somehow, dawn arrived, my companions of the road re-appeared, and we moved on, through Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, to Iowa, along Route 30, the old Lincoln Highway, which would take me all the way to Rock Springs in western Wyoming. Green country, endless rows of corn just coming up to ankle height, squared-off dirt section roads enclosing farmland, and that corn stretching to the ever-receding horizon. The Lincoln Highway was mostly two-lane, sometimes three-lane, blacktop, and you had to be careful, going fifty-five miles an hour or more, watching for farm tractors turning out of the section roads onto the Way West.

Crossing the Mississippi River meant little to me, but the thought of crossing the Missouri, the route of Lewis and Clark and of the fur-trading keelboat men, the route to the Big Sky country, stirred my blood.

We had stopped for the night in the college town of Ames, Iowa, where the world-weary proprietress of a homey motel looked doubtfully at the three of us when Gene asked for a “double room.” Accepting my pleas to be allowed to sleep on the floor in my bag between the two beds, and possibly touched by the sight of the swollen lumps on my face, she agreed to charge only my companions. I dined upon what I believe was my third burger and malt of the trip, and got a good night’s rest on the hard floor.

The third day saw another endless haul, this time across Nebraska and Wyoming. On the outskirts of a small Nebraska town, I saw a posted sign that has puzzled me to this day: ‘Swedes—we don’t want your kind here. Move on.’ It was not the bigotry, but the unusual choice of ethnicity, that I have not been able to comprehend.

Southern Wyoming was mostly dry and broken country, marked at long intervals during the last century where the head of track of railroad construction had left a good-sized town. And each town, in descending pecking order from east to west, had been graced with a public institution: Cheyenne (State Capitol), Laramie (State University), Rawlins (State Prison), and Evanston (State Mental Hospital).

In the mid-afternoon, we arrived in Rock Springs, a dusty grey straggling place that certainly looked to me to be at least seven parts rock to less than one part springs. Gene, Allan, and I grunted our good-byes, I stepped out of the Chevrolet, hauled out my Gladstone, and stood on the north-east corner of Route 191 and the Lincoln Highway. I set my bag between my feet, and lifted my thumb. I was on my own, headed north.

Within five minutes, a red Thunderbird stopped. “Well, where you headed, son?” The driver was perhaps ten years older than I was, and he had the boots and the big hat to go with his smile.

“Aiming for Alaska to find work this summer, sir. Name’s Steve.” I never did get his name, or perhaps he never gave it.

“Well, I can get you the first hundred miles or so along your way, so get on in.”

We roared north in the dimming but crystal light, the two-lane asphalt cutting through bunchgrass that seemed to go on forever. Antelope raced along beside the Thunderbird, and occasionally sprang with daredevil leaps across the road ahead of us. As we crossed the Fremont County line, I was regaled by my native host with stories of the bloody wars between cattleman versus sheepherder of only seventy-five years ago. He was clearly partial to the cattlemen’s side. “Well, there’s a pretty fair roadhouse up ahead a few miles. I’ll buy you a Wyoming steak, son.”

My host seemed well, perhaps intimately, acquainted with both the waitress-cum-bartender and the surly cook. He introduced me as if we had been long-time buddies, and we two solitary patrons ate two and a half of the biggest (and toughest) steaks it has ever been my pleasure to consume. The roadhouse restaurant-bar consisted of a huge room with peeled wood beams and a lingering aura of what it must be like on a wild Saturday night, out here in the middle of nowhere. We drank what I later came to recognize as “western” coffee: black and watery, as opposed to “cowboy” coffee: black and strong enough to float the spoon. The pie of last season’s berries was sweet, juice-drippy, and measured about three wedges to the circle. We bid our hostess adieu. “So long, darlin’s, stop by if you get back this way,” she waved. We were off, with the sun lying just above the westward ridges.

I asked my host if he knew of a good place along the road up ahead where I could roll my bag out for the night.

“Well, son, it cools down pretty quick at dark around here, but there’s this old line shack up ahead a few miles. Only used at the spring and fall round-ups. Nobody will mind if you bed down in there.” And, true to his word, he dropped me off just before sunset, in Cowboy Heaven. Then, to my astonishment, he U-turned the ‘Bird, and roared back down the way we had come, no doubt to engage the waitress in further conversation.

It was a narrow, well-grassed valley, bordered by aspen rising to the ridges. In the river meadow behind the sagging wooden buildings and empty corrals, cattle and antelope were grazing together, side by side.

The old, slant-leaning bunkhouse itself was rusty and dusty and empty; a broken windowpane was loosely stuffed with a rag. Inside the building was one metal bedframe with a rolled-up old mattress. There was an axe with a splintered handle, and a cast-iron stove, and outside a stack of bone-dry wood stood by the corrals. I split enough of the wood to warm myself against the gathering evening chill. I fired up the stove, priming it with pages from last autumn’s Plnedale Gazette, rolled my bag out on the mattress, and fell asleep, listening to the scurrying of the kangaroo mice on the bunkhouse floor, the owls hooting in the moon-risen meadow, and the quickening breeze in the aspen. It was June 14, 1957, and my heart was easy in my breast.

I awakened suddenly, disoriented, perhaps with the awareness, or the sixth sense, that something was not right. A pale cottony white light filled the bunkhouse, suffusing everything with a silent glow that was almost, but not quite, luminescent.

I looked at my watch. The hands showed seven-fifteen, but the second hand was not sweeping. I put the watch to my ear, and realized it was stopped; it must have been damaged while I was splitting wood.

Moving over to a grimy windowpane, I saw that the same white light was shining everywhere. Had I died of blueberry pie overdose, and truly woken up in Cowboy Heaven? Apparently not quite yet; for on the ground lay three or four inches of powdery snow, with more coming down by the bucketful. What time was it? Probably at least mid-day, given the brightness of the light. My groggy mind now remembered something half-heard on the radio, was it only yesterday, short of Rock Springs? “Possible late-season blizzard moving up from Colorado.” My brain, still set to Eastern time and clime, had refused to register the possibility of a sudden snowstorm in mid-June. But here we were.

I packed and rolled my bag, slipped the poncho over my head (thus exposing the sleeping bag to the falling snow), and felt my way out the twenty yards to the road. Nothing was in sight in either direction through the diminished visibility. No tracks lay on the road; none made by human, animal, or Detroit. Back in the shack, I considered my situation more carefully. While I might get a bit hungry, I had at least a bag of peanuts and half an O’Henry candy bar in my Gladstone, and plenty of stovewood to keep warm by, and to melt snow water. So I was not without food or drink. A car, or a plow, was sure to come through that day or the next, this was the major road between Rock Springs and Jackson Hole. Things would work out; all I had to do was to be patient.

It couldn’t have been more than fifteen minutes, with the snow still coming down hard, before I heard the sound of a car grinding up the road from the south. I grabbed my stuff, ran out to the road, and made the foolish gesture of sticking out my thumb, instead of waving my arms.

The car was all black, an ancient Nash, perhaps ’46 or ’47, with a dent for every mile. Behind it was towed a black flatbed trailer, and atop the trailer was secured, upright, a black Harley-Davidson, equally ancient and dented. The conglomeration came to a stop, skidding a bit beyond me in the powder. The sight presented an ominous and eerie apparition—a world of black on white.

He was all in black as well: black Stetson, black hair, black ‘cycle jacket, black jeans, black boots, and black gloves. He was stringy and well-used, and the three days’ stubble on his cheeks was, well, black.

He rolled the window down, squinting against the snowflakes and the white light. “Hey, bub, you sure picked a funny day for hitch-hiking. Where you bound?”

“North to Alaska, Mister.” The phrase was from the John Wayne movie of the same name, and its theme song, which proclaimed: “North to Alaska. We’re going North, the Rush is on!”

“From the looks of this weather, we must be almost up there already, bub. Hop in, I’ll take you to Jackson, just twenty miles up this Hoback Canyon road. You can get breakfast there.”

“Breakfast? It must be afternoon by now.”

“Shoot, bub, it’s not even seven-thirty on a beautiful morning in full Wyoming spring conditions. C’mon, hop in.”

He looked to me like Jack Palance, the bad black-hatted gunfighter in a number of classic Westerns, or maybe like Richard Boone, the antihero hero of the 1950s TV Series, “Have Gun, Will Travel.” I don’t know if he was a gunfighter or not, but he surely wasn’t bad. His name, I kid you not, was, of course, Jim Black, and that old Nash was warm and cozy and full of song and laughter as we skidded and sputtered slowly through the snowy Hoback canyon and came down into the little town of Jackson.

The snow stopped and the sun shone as we drove down the main street, with its many false-front buildings, themselves fronted by wooden boardwalks. Jim slid his rig to a stop in front of the Silver Dollar Bar and Café. “Whoa there. Get yourself the best breakfast in town here, bub. Try the Silver Dollar pancakes.”

I offered him breakfast, but he declined. “Got to get this rig up over to Cody for the bike races, and had best be moving along. There’ll be snow aplenty time I get to Yellowstone”

“Those races might be quite a goat-rope, if it’s snowing as much up there as it was where you picked me up. Thanks, and drive carefully.”

Jim laughed, winked, waved a gloved hand, and was gone, whistling one last chorus of “North to Alaska.”

I pushed my way in through the bat-wing doors (they might probably be there to this day, if you don’t believe me), took a revolving stool at the counter, and gazed down at the rows and rows of silver dollars inlaid all along the counter (which at night was the bar, and no doubt even busier than for breakfast). I left my Gladstone, minus the shaving kit and towel, under the watchful but friendly eye of the grizzled old-timer seated next to me, and cleaned up in the washroom. Then I cleaned up again, this time on the best plate of pancakes and link sausage and (western) coffee I could ever remember eating.

Moving out onto the opposite side of the sunlit main street, I lifted my thumb once again. I had barely time to feel those pancakes begin to settle before a brand-new Volkswagon bus stopped.

Its driver looked like he would be more at home in Olde Lyme, Connecticut than in Jackson, Wyoming. He was clad in khaki ‘chinos’, an open-necked short-sleeved shirt, and had one of those little plastic thingy’s in his breast pocket with several pens, and the obligatory 1950s slide-rule. But, like everyone else in western Wyoming, he seemed to be chronically-infected with Smile Disease. “Where can I take you, my young friend?”

“Name’s Steve, and I’m headed north, up to Montana and then to the AlCan for Alaska. Appreciate any lift you can give me.”

“Well, I can only get you five miles or so up the road, but at least that’s a start out of town, and there’s sure to be someone who will be heading north.”

We hung a left at the little park in the center of town, the one with arches of elk antlers framing the entry paths, and moved north in the lee of a long bluff to the west.

“That’s Gros Ventre, Fat Belly, Butte. A lot of things have French names around here, tagged by the French Canadians who came down into this country after beaver. They were among the first of the Mountain Men. I’m turning off west just after we pass the Butte, over to Warm Springs Ranch.”

I suppose the words “Mountain Men” set the fever alight in my brain, and then, as we came up to the end of the Gros Ventre Butte, I saw them in the morning sun, standing to the northwest and front-lighted from the east. I saw them, something lifted up inside me, and I never have been the same, even to this day, forty years and more later.

There they stood, compact in an uneven broken line, glistening crests of rock and snow and ice. They were just a short range, separated from the rest of the chain of the Rockies by flat spaces to north and south, and cut by deep west-running canyons between the peaks. Though you could not, from where we were, see the chain of blue lakes along their eastern front, the green dip of conifers told you the lakes were there.

“What are those mountains, mister?”

“Those, my boy, are the Grand Tetons, and out in front of you is Jackson Hole. The Snake River runs through it. The Mountain Men crossed through the Hole in the 1820s and 30s, looking for beaver, moving back and forth to their yearly rendezvous sites: west of the range in Pierre’s Hole, southwest on the Bear River, over southeast on the Sweetwater, and down south of the Hoback on the Green River. They gathered each spring, coming in from wherever they had spent the winter, to trade, to raise hell, and to plan the year’s beaver hunts. Jackson Hole was a sort of center-point, a cross-roads on their trails of exploration during the high time of the Mountain Men. They called it a ‘shining time’, and those are the Shining Mountains. I’ve always wondered where that phrase came from, though it’s plain to see what it signifies. Last year I read that when the French explorer, Pierre La Verendrye, was looking for furs way over north and west of Lake Superior, back in the 1740s, almost a hundred years before the Mountain Men got out here, the Indians told him that far to the west there were mountains ‘that shined by night as well as by day.’ They had it right, for sure. Just be here in the moonlight, and you’ll see.”

Thoughts of Alaska vaporized. This was my place.

“Stop the car. I mean, slow down, please. Do you think there might be any work around here, mister? I can do most anything, especially if it’s outside.”

“Well, I don’t know, but there is the National Park headquarters up the road there at Moose, and I think they usually take on seasonal help for the summer. Tell you what, I’ll run you up to the park, past Moose Junction, it’s just a few miles further on than I was going anyway, and you can try your luck.”

We drove through the valley of Jackson Hole, elk and trumpeter swans to the right of us in the National Wildlife Refuge. The visual passage was clear to the north, and always the peaks lay to the west. We dipped down to cross the Snake at Moose Junction, passing the Chuckwagon, a tourist restaurant under tent canvas, with huge grates and cauldrons already firing up. At the Chuckwagon, I came to learn, if it was made of beef, you could order it. If it wasn’t made of beef, they were temporarily out of it. Alongside the river lay the log-framed Chapel of the Transfiguration, through whose huge altar window the simple wooden cross was silhouetted against the soaring peaks. On the other side of the road was a small general store, also of peeled logs, with a telephone hung outside, next to a Sinclair Oil gasoline pump.

Once past the river bridge, the road wound up onto a forested benchland fronting the mountains. A sign proclaimed: “Welcome to Grand Teton National Park.”

I hopped out, offering my thanks to the driver for going considerably out of his way for my convenience, and walked into the entrance road.

Park headquarters was a cluster of log buildings with green roofs, surrounded by lodgepole pine forest. There was a jumble of jeeps and pick-ups in the central yard, and nobody much was around; it was Sunday morning.

I knocked on the door of the building marked “Central Administration.” Being hailed in, I faced a youngish man with a leathered face, a receding hairline, and a nicely-developing beer gut, sitting slouched behind a desk. On the desk was a sign, “Assistant Superintendent.” But from under the desk stuck out a pair of well-used, and well-oiled, work boots, and the hand he waved me in with was clean but heavily callused.

“Sir, I was headed for Alaska, but I saw those mountains. Any chance you have work for me? I’m strong and not too bright, and I can do most anything.”

“Well (that word seemed to be the way to begin any sentence in these parts; sort of a front-end punctuation mark, like the inverted question mark in written Spanish), we filled our Trail Crews last week, but I had some Eastern kid quit on me this morning, so I do have one place open, and tomorrow is Monday, and Billy Jiggs from Driggs has got to take a crew up on the Hidden Falls Trail. Would you mind working in the woods? You’d have to spend some time in the mountains.”

“Well (by now I had become similarly speech-affected), I guess I could do that, if you really need somebody.” I am certain he saw right through my affected nonchalance; eagerness must have been all over my face. He tried to suppress a grin.

“Then you’re in luck, and we have a deal, young pardner, as long as you are not on the run or some kind of dope fiend, and can sign your name. Just throw your gear over in the bunkhouse, and we can fiddle with Uncle Sam’s paperwork tomorrow, early morning. If you’re hungry, there’s probably some cold pancakes left in the kitchen”

And, as I was backing out the door, he added, “Oh, yeah, by the way, what’s your name, so I can tell Billy.”