Читать книгу COSSAC - Stephen C. Kepher - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление— 3 —

“FOR WHAT ARE WE TO PLAN?”

Fifteen months before General Morgan’s fateful day at New Scotland Yard, the British Joint Planning Staff in December 1941 submitted an analysis to the COS that was a general outline of what a reentry into the Continent might look like. The COS then asked the Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, the newly appointed Gen. Sir Bernard Paget, to review the paper and to consult with the commanders of Bomber Command, Fighter Command, and the Royal Navy’s Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth, in providing his evaluation.1

In January 1942 the COS gave further guidance to Paget:

German morale and strength in the West may deteriorate at any time in the future to a degree that will permit us to establish forces on the Continent. You are, therefore, to plan and prepare for a return to the Continent to take advantage of such a situation….

You should continue your study of a major raiding operation against one of the main French Atlantic ports in case it becomes desirable to carry one out but preparations for such an operation are not to be allowed to delay your preparations for your primary task.

The Advisor on Combined Operations [is] to be consulted at all stages of the planning.2

Around the same time, Mountbatten and Commo. John Hughes-Hallett, representing Combined Operations, were invited to join General Paget in attending a staff exercise conducted by the various Home Forces commanders. Each of the generals and their staffs were instructed to prepare and present “an outline plan for the seizure of the Cherbourg Peninsula, to hold it for a week, and then withdraw back to England.”3 In other words, to plan something similar to SLEDGEHAMMER, or IMPERATOR, but in Normandy, not the Pas-de-Calais.

Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery, commander of South Eastern Command, presented last, and “after explaining the hazards of such an operation, went on to point out that it would be easier and more worthwhile not to withdraw the troops but to flood the Carentan Marshes and hold the Peninsula.”4 Although this would create a lodgment and a base for future offensive actions, Montgomery did not address how the troops were to break out and drive toward Germany through the German troops that undoubtedly would be in strong defensive positions on the other side of the marshes. Still, it made a change from considering the Pas-de-Calais.

From these modest beginnings emerged the Combined Commanders, sometimes called the Combined Commanders-in-Chief. The Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, Sir Bernard Paget; Air Officer Commanding Fighter Command, Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory; and Sir Charles Little, Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth, had many duties. Being the Combined Commanders was a somewhat informal collateral duty as the British armed forces slowly reoriented themselves from a purely defensive posture to consideration of offensive action from the British Isles. The RAF’s Bomber Command went its own way as a result of a directive issued by the Air Staff in February 1942. It was authorized to bomb Germany “without restriction,” and Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris went at it with a will.5 He waged his own offensive against German cities, believing that charring enough German acreage would make a cross-Channel attack unnecessary.

The Combined Commanders were required to consult with Combined Operations Headquarters when developing their plans. Mountbatten’s unique position of being both head of an independent headquarters and a de facto member of the COS created problems on occasion, particularly if he disagreed with the Combined Commanders, although perhaps less often than it could have done.

The Combined Commanders took up the question of crossing the Channel and reached the conclusion that the Pas-de-Calais was the proper landing area, for one chief reason: in 1942 RAF fighters were unable to provide air cover in any meaningful way over other possible beaches. The Pas-de-Calais was also the closest viable landing site to Antwerp, which was identified as a critical port of supply for a drive into Germany. Mountbatten argued instead for the Cherbourg Peninsula (and, by extension, for the French Atlantic ports)—having seen the merit in the idea presented by General Montgomery and made it his own. He also thought that air cover could be provided by fitting the fighters with auxiliary fuel tanks.

Gen. Sir Alan Brooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff and chair of the COS, also believed that the Pas-de-Calais was the proper location. On 10 March 1942 Mountbatten attended the COS’ weekly meeting for the first time. As noted in Brooke’s diary, they discussed “the problem of assistance to Russia by operations in France, with [a] large raid or lodgment. [It was] decided [the] only hope was to try to draw off air forces from Russia and for that purpose [the] raid must be carried off on Calais front. Now directed investigations to proceed further.”6 Still, Mountbatten was keen to go his own way.

He continued to press for Normandy and the Baie de la Seine in meetings with the Combined Commanders. He next brought this up at a meeting of the COS on 28 March. Mountbatten, having a choice of sitting either with the COS or with the Commanders, sat with the Commanders and, when his turn to speak came, “roundly denounced their plan [for the Pas-de-Calais]…. In the end the Commanders left the room with orders to work on the Normandy plan.”7 However correct he might have been, the Commanders had no great appreciation for the assistance that Mountbatten had given them. There was, as a result, some amount of friction between the various headquarters, and both Paget at Home Forces HQ and the RAF still believed in the Pas-de-Calais.

Early British planning for crossing the Channel was also informed by their preparations for a German invasion in 1940. Hughes-Hallett was Mountbatten’s naval advisor at Combined Operations and was as expert in the details of amphibious assault as almost anyone in Britain. He noted that the experiences of anti-invasion planning in 1940–41 brought to light “the enormous magnitude of problems to be overcome before even a minor amphibious operation could be … successfully carried out.”8 The tides in the Channel are difficult, particularly for small craft. Both the RAF and the German air force, the Luftwaffe, had major forces that would have to be brought to the fight. Logistical support, specialized training for the crews operating the landing craft if not the assault troops as well, and timing issues were staggeringly complex. In Hughes-Hallett’s opinion, there were few army officers who had any real understanding of the magnitude of the problem, except perhaps for those few who had been personally involved in planning amphibious attacks or training troops for them.

The Combined Commanders had planners, of course. Brig. Colin McNabb for the army, Commo. Cyril E. Douglas-Pennant for the navy, and Air Marshal Sholto Douglas were the head planners. As General Morgan later observed, “Just as no nobleman of olden times was apparently a nobleman unless he employed his tame jester, so in 1943 no commander was alleged to be worth his place in the field unless he retained his own planner.”9 This was a comment on the proliferation of planners, not their quality. McNabb worked well with the Americans at ETOUSA and went on to serve as brigadier general staff for Kenneth Anderson’s First Army in Tunisia, where he was killed in combat. Douglas-Pennant commanded the naval assault forces for GOLD BEACH on 6 June, and Sholto Douglas became the commander of Coastal Command in January 1944, after serving as the senior RAF commander in the Middle East.

A principal problem for the planners was the custom of the COS to require them to examine problems and design plans without a specific operation associated with the plan they were asked to create. Consequently, their work was subject to constant revision by higher authorities. “Each such revision was liable to call for variation or amendment of the plan put forward, in many instances necessitating cancellation or re-execution of work already put in by troops on the ground.”10 Another problem was that the fighting was going on in the Mediterranean, was likely to remain there, and, consequently, planners in London were far removed from any possibility of action.

The “Planning Racket”

In early 1942, with the U.S. Army’s Special Observer’s Group in London and its evolution into ETOUSA, the Americans arrived, full of enthusiasm and lacking experience.

On 7 February 1942 Col. Ray Barker, USA, commander of the 30th Field Artillery Regiment at the newly built training facility of Camp Roberts in California, received orders to report to the New York port of embarkation. He stopped in Washington, D.C., on the way and discovered that he was to take over the artillery section of the Special Observers Group in London. This meant that his promotion to brigadier general was deferred, but he told the chief of field artillery, “Never mind about the promotion part of it, if I can just go where the war is.”11 Having spent some amount of time in England in the interwar years, and being a student of British history, Barker thought that he could be effective there.

In a bit of cloak-and-dagger work, the group traveling to England were given civilian passports and wore civilian clothes on the trip, as they went by Pan American Clipper from New York to Bermuda, to the Azores, and then to Lisbon. From Lisbon they went to Shannon Airport in Ireland on a British Overseas Airways aircraft, then flew to Poole (near Bournemouth on the Channel coast) and went by train into central London.

The London they encountered had adapted to war. In a series of “Letters from London” for the New Yorker magazine, journalist Mollie Panter-Downes sketched out what life in the British capital was like during the Blitz.

Life in a bombed city means adapting oneself in all kinds of ways all the time. Londoners are now learning the lessons, long ago familiar to those living on the much-visited southeast coast, of getting to bed early and shifting their sleeping quarters down to the ground floor.12

… For Londoners, there are no longer such things as good nights; there are only bad nights, worse nights and better nights. Hardly anyone has slept at all in the past week. The sirens go off at approximately the same time every evening, and in the poorer districts, queues of people carrying blankets, thermos flasks, and babies begin to form quite early outside the air-raid-shelters.13

… Things are settling down into a recognizable routine. Daylight sirens are disregarded by everyone, unless they are accompanied by gunfire or bomb explosions that sound uncomfortably near. A lady who arrived at one of the railway stations during a warning was asked politely by the porter who carried her bag, “Air-raid shelter or taxi, Madam?”14

In London Barker joined what was then a group of about ten officers. While initially tasked with planning the deployment and training of artillery units expected to be arriving as part of BOLERO, he was quickly named head of the war plans section. While that may not have seemed an obvious assignment for a field artillery officer, he explained that he was picked “because I happened to be standing there and no one else [was] available.”15 From then on, he was involved in what he called the “planning racket.”

Initially there were only a couple of U.S. Army officers involved in planning relating to the eventual reentry into the Continent. While he requested and got additional support, he felt that the first thing he needed to do was “to find out what the British were doing in this field.”16 This is when Barker discovered the Combined Commanders and their planners. While building his own staff, Barker worked in close daily cooperation with the British planners. Asked if he had been assigned to work with the British, Barker replied, “No one actually told me that I should associate myself or collaborate with these people; it was just the obvious thing to do.”17

Barker and his group got to work on preparations for BOLERO as well as plans for SLEDGEHAMMER and ROUNDUP. In July, there was what his then boss, Dwight Eisenhower, described in his diary as a day that might become “the blackest day in history.”18 SLEDGEHAMMER was cancelled. But not entirely. The COS decided at its meeting of 22 August 1942 that “for purposes of deception and to be ready for any emergency or a favourable opportunity, all preparations for ‘SLEDGEHAMMER’ continue to be pressed … and [recommended] that a Task Force Commander be appointed with authority to organize the force, direct the training and maintain a contingent plan for execution.”19 Both Paget and Mountbatten were at the meeting, as was Pug Ismay.

At the same meeting, Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal, acting as chair in the absence of General Brooke, quoted from a Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) memorandum written the prior month, saying in effect that as a result of TORCH going forward, “we have accepted a defensive encircling line of action for the continental European theatre … but that the organization, planning and training for eventual entry in the Continent should continue [in case there was] a marked deterioration in German strength … and that the resources of the United Nations available after meeting other commitments, so permit.”20

General Paget noted that the planning for ROUNDUP would be based on working out the minimum requirements for forcing an entry into the Continent against weakening opposition. He also felt that, at this time, there was “no need for the Supreme Commander-in-Chief or his Deputy to be nominated.” Mountbatten added that TORCH would employ every available landing craft and trained crew, and no operation of any scale could be mounted from the UK before March or April of 1943.21

The vision in August 1942 was to prepare contingency plans for an operation that could not occur before the spring of 1943, using the minimum force available after all other commitments were met, assuming that German resistance had weakened, and without identifying a commander or his deputy or identifying units that would be involved.

After the Dieppe Raid, planning continued. In late September 1942 a deception exercise, Operation CAVENDISH, was postponed for a second time and the Commander-in-Chief, South Eastern Command, Lt. Gen. J. G. Swayne, wrote to Paget arguing that the operation should be cancelled. Originally planned for October 1942 and now proposed for early November, the operation was an attempt to convince the enemy “that an invasion was being staged, though this deception was always difficult on account of the small number of modern landing craft available.” General Swayne pointed out the obvious fact that the “enemy must know that the possibility of sufficiently long periods of suitable weather being obtainable in November are extremely remote…. I am informed by A.O.C. 11 Fighter Group that from the air point of view November would be very unsuitable for this enterprise.”22 We can infer that the operation was another attempt to lure the German air force into battle while a sea-based feint approached the Pas-de-Calais. As the general noted, weather over the Channel in November is rarely favorable for such operations; indeed, it was a basic principle (at least for experts like Hughes-Hallett) that the Channel’s “invasion season” ended in September. The operation was cancelled.

Another operation, titled OVERTHROW, was to be a major cross-Channel effort and required coordination with Bomber Command to ensure that pre-invasion targets like gun emplacements and all forms of transport were attacked, which meant that Bomber Command would have to stop bombing cities and start bombing tactical targets. In part, this was to test if bombers could hit targets like gun emplacements and to find out what the level of damage might be. That operation also didn’t get past the planning stage.

By now the long-considered operation to capture the Cherbourg Peninsula had a code name as well, and by September 1942 outline plans for a similar operation focused on Brittany were being considered.

By the end of September 1942 the Combined Commanders and their planners were considering the sixth draft of a memorandum to the COS, “Future Planning for Operation ROUNDUP” and the third draft of a similar memo, “Offensive Combined Operations in North-West Europe in 1943–1944.” The memo for ROUNDUP outlined what the planners believed a theoretical phase 2 would look like—assuming the Allies had successfully reestablished themselves on the Continent. They identified three main goals: the capture of Paris; the capture or peaceful occupation of the Atlantic ports of Brest, Lorient, Saint-Nazaire, and Nantes, in part for a secure rear area to build up forces and in part because they expected the French would have to be fed with food shipped into the country; and a drive to capture Antwerp.

The commanders and planners requested that the COS grant them the authority to “frame an outline plan … basing it on the assumption that the full number of divisions included in the [previously] approved outline plan for Phase I will be available; and to prepare this outline plan in cooperation with the staff of the Commanding General ETOUSA, on the distinct understanding that the completed plan is subject to his approval and may therefore require revision.”23 That is, they asked for permission to plan given a certain set of assumptions, knowing that the American commander might modify or reject their plan after the work was completed.

The second memo recommended that “raids, whether designed primarily to provoke air battles under conditions favourable to ourselves or for some other purposes, must be closely co-ordinated with the approved strategy for 1943 and 1944” and not just be done for their own sake (a reference, perhaps, to Dieppe) and that “a plan for moving an Army into Europe in the event of serious deterioration in German morale should be prepared in outline.”24

In the memorandum the planners also proposed consideration of an alternative to the existing ROUNDUP plan. Noting that the capture of the Pas-de-Calais might be a “very hazardous operation,” the planners proposed the capture of Le Havre, Rouen, and Cherbourg at the earliest opportunity. If German forces in the Pas-de-Calais could be contained by a series of major raids, then a “land and sea attack on the Cotentin [Cherbourg] Peninsula (could be) increased in strength.” They went on to state that while prior planning had been based on the idea of simultaneous assaults over a wide front, consideration should be given to launching a series of assaults, “timed and directed to take advantage of the then existing circumstances, and supported in each case by a maximum possible concentration of air and naval effort…. We might hope to deceive the enemy as to whether he was still faced with major raids, or feints or with our main effort.”25

The concepts in these memos were put forward as a basis for operations in 1944. The Combined Planners then asked the COS if they agreed in principle with the concepts and if they wished the planners to begin a detailed study of the proposed alternatives.

In broad terms, these ideas were not far off from Churchill’s vision of what a cross-Channel attack might look like. In his note to the British COS regarding Operation IMPERATOR, Churchill noted that “if this were one of a dozen simultaneous operations of a similar kind, very different arguments would hold” versus those against the operation in question.26 His vision in June 1942 was of “at least six heavy disembarkations at various points along the north and west coast of Europe, from Denmark and Holland down the Pas de Calais [‘where a major air battle will be fought’] to Brest and Bordeaux. He also advocated ‘at least a half a dozen feints’ to mystify the enemy. These armoured landings would be followed by a second wave of heavier attacks at four or five strategic points, with the hope that three might be successful.”27 He envisioned a third wave once a port had been captured and opened.

There was, of course, no calculation of resources needed or resources available, nor any particular target date for the operation, nor any force commanders to lead beyond the roles to be played by the Combined Commanders.

The Combined Planners suffered from being a British, as opposed to an Allied, group. While it was true that there was ongoing, informal collaboration between Barker’s group at ETOUSA and the planners, they reported to the Combined Commanders, who then reported to the British COS. The blunt-speaking Hughes-Hallett (who was called Hughes-Hitler behind his back28) said of the planners, “I could not take the work very seriously. The combined staffs of the Combined Commanders were so large that when they had plenary meetings it resembled a meeting of Parliament itself—with no equivalent of Mr. Speaker to enforce rules of order.”29

The questions the planners had were not being answered. The projects were beginning to feel like exercises that were never to be executed. In addition to the fighting in North Africa, initial plans for attacks on either Sardinia or Sicily were being considered, which left few resources for the planners to use for any cross-Channel operation. It seemed that the Allies were going to stay in the Mediterranean for a long time.

At the end of October 1942 the COS accepted a memorandum from the Joint Planners, which was a statement of the British military’s strategic outlook. Among the analyses was the following:

Despite the fact that a large-scale invasion of Europe would do more than anything to help Russia we are forced to the conclusion that we have no option but to undermine Germany’s military power by the destruction of the German industrial and economic war machine before we attempt invasion. For this process, apart from the impact of Russian land forces, the heavy bomber will be the main weapon, backed up by the most vigorous blockade and operations calculated to stretch the enemy forces to the greatest possible extent….

Even when the foundations of Germany’s military power have been thoroughly shaken, it is probable that she will be able to maintain a crust of resistance in Western Europe. We must have the power to break through this crust when the time comes. We must therefore continue to build up Anglo-American forces in the European Theatre in order that we may be able to re-enter the Continent at the psychological moment.30

As for amphibious operations against France, the paper suggested more “Dieppe”-type raids (obviously with better outcomes) as well as large raids of longer duration against high-value targets and smaller commando raids.

Operation SKYSCRAPER

According to Barker, now a brigadier general, he and the other U.S. and British planners grew increasingly frustrated throughout the fall of 1942. In December a British major general, John “Sinbad” Sinclair, an officer in the Royal Horse Artillery who had started out in the Royal Navy, joined the planners. Sinclair and Barker finally got down to what Barker felt was constructive planning.31

On New Year’s Day 1943 Barker and Sinclair agreed that they had accumulated large amounts of data, information, intelligence, and tentative plans, and they felt it was necessary to “produce something that would bring it all to a head and come up with a definite conclusion and a definite recommendation.”32 What they produced on their own initiative became known as Operation SKYSCRAPER.

SKYSCRAPER, an outline plan submitted to the Combined Commanders on 18 March 1943, was an impressive document and unambiguous about its purpose. The first sentence reads, “The object of this paper is to obtain decisions on certain major points which must govern not only the planning for a return to the Continent against opposition, but more particularly the organization, equipment and training of the Army in the United Kingdom during 1943.”33 Barker and Sinclair note that the plan had not been approved by the Combined Commanders nor had all the details been worked out. That is, they acknowledged that it was their idea to create the document and send it up the chain of command, and it was not the result of a directive to generate another study.

They go on to make the point that “it is generally agreed that the original ‘ROUNDUP’ plan is not a feasible one and some other basis is therefore necessary.” Unlike earlier plans, Barker and Sinclair proposed a landing concentrated on the beaches in front of Caen in Normandy as well as landings on the Cherbourg Peninsula. Starting with the premise of a landing against determined resistance, not a weakened or demoralized enemy, they estimated the initial assault force at ten divisions afloat and up to four or five airborne divisions, plus commandos, engineers, and other special troops. They also estimated the numbers of all the specialized landing craft that would be needed.

While their scenario involved three distinct phases from initial landings to the capture of Antwerp, the key message to the Commanders and the COS comes toward the end of the summary. First there is an acknowledgement of the size of the force contemplated or the “bill” for the operation. They acknowledged that the bill “is a large one, and obviously not to be accepted lightly.” They go on to state, “A warning must, moreover, be sounded with regard to the degree of opposition which could be overcome if the ‘bill’ is met, and the resources provided. The ‘bill’ is for THE MINIMUM RESOURCES LIKELY TO PROMISE SUCCESS AGAINST APPRECIABLE RESISTANCE…. The margin between success and failure would be very narrow.”34 Because they were not presenting a plan to deal with weakened German forces on the brink of collapse, the margin would always be narrow for troops fighting their way ashore from the Narrow Sea.

The most remarkable part of the plan comes at the end of the summary, when Barker and Sinclair demand that the COS make a clear and unequivocal choice:

An invasion of the Continent in the face of German opposition is such a specialized problem that there is no chance of undertaking it successfully without careful preparation over a long period…. The decision as to whether or not we prepare the Army specifically for this purpose cannot be deferred…. The rock bottom of it all is, however, this: knowing the very great difficulties in provision of resources, for what are we to plan and prepare?

If we are to plan and prepare for the invasion of Western Europe against opposition it must be on the understanding that the resources considered necessary are fully realized and that it is the intention to provide them. Given that knowledge, we can go ahead on a reasonably firm basis.

If, on the other hand, it is clear that such resources can in no circumstances be provided, then it would seem wise to accept at once that invasion against opposition cannot be contemplated….

In conclusion, a decision on the points raised … is a matter of urgency as a basis for planning and preparation. As already pointed out, to defer the decision is to decide not to be ready.35

Paget sent the plan to the COS, who did not respond directly, although they noted that some of the assumptions regarding the scale of German resistance were vague. With the dramatic changes in circumstances that were occurring across the broad European Theater in 1943 (which are addressed in chapter 7), it could hardly have been otherwise. Paget believed that the COS were “unfavourable to the plan because of the huge bill for resources.”36 SKYSCRAPER did, however, make up a significant part of the stack of papers that Ismay gave Morgan to read before presenting to the COS. Morgan, having read SKYSCRAPER and the other material, made a recommendation in mid-March that clearly convinced the august body of senior officers that he was the person for the job. What exactly did he say?

While he made no attempt to delve into strategy or tactics, Morgan argued that it was necessary for the staff to be a completely joint and combined British-American effort in every detail from the very beginning. It needed to be slotted into the existing chain of command but be independent enough to seamlessly become an operational headquarters when the time came. More importantly, Morgan stressed that the prior habit of separating planning from execution could not continue. It would be necessary “for all concerned to throw their hearts over the jump and make up their minds there and then that the campaign had already begun, that there should be no question of producing just another plan to be a basis for future argument.”37

In the absence of a supreme commander, all that the commander would need must be provided for: forces, a supply system, command and control systems, and, most importantly, “a plan of action both basically sound and yet sufficiently elastic to admit of variation as might be necessitated by developing circumstances.”38 This was a somewhat elaborate way of saying that the plan needed to be good enough to be approved but capable of modification by the commanders as needed without disruption to the basic concept. Morgan also recommended that the senior planners hold the rank of major general and not brigadier as they would have to interact on a daily basis with the War Office and other ministries. To get those ministries to respond, it would be necessary to have sufficient rank to gain and keep their attention.

Morgan had trained troops for amphibious assaults and had planned amphibious operations. As commander of 1st Corps, he was known to Mountbatten and Combined Operations. He had also successfully, if briefly, worked with American forces, and that was not a universal accomplishment. At the time it was widely believed that the supreme commander would be British, with an American deputy, and so it made sense for the chief of staff to be British as well. All of this led to the British COS agreeing on 1 April that Morgan was the man for the job, however the job was going to be defined.39

Notwithstanding Morgan’s impression of the COS’ reaction to his recommendations and Mountbatten’s congratulations, his appointment to head this new planning staff did not come at once. It took about a month to work out details of Morgan’s appointment and for the CCS to issue the directive to him that outlined his responsibilities. Formally issued on 26 April, it was made available to Morgan in draft form in advance, and the British COS authorized him to act on the assumption that approval of his appointment would occur. The key elements of the directive read:

The Combined Chiefs of Staff have decided to appoint, in due course, a Supreme Commander over all United Nations forces for the invasion of the Continent of Europe from the United Kingdom.

Pending the appointment of the Supreme Commander or his deputy, you will be responsible for carrying out the above planning duties…. You will report directly to the British Chiefs of Staff….

You will accordingly prepare plans for:

(a) An elaborate camouflage and deception scheme extending over the whole summer with a view to pinning down the enemy in the West and keeping alive the expectation of large scale cross-Channel operations in 1943. This would include at least one amphibious feint with the object of bringing on an air battle employing the Metropolitan Royal Air Force and U.S. Eighth Air Force.

(b) A return to the Continent in the event of German disintegration at any time from now onwards with whatever forces may be available at the time.

(c) A full scale assault against the Continent in 1944 as early as possible.40

Morgan asked for clarification regarding the last point, feeling that “as early as possible” was not particularly precise from a planning standpoint. His question went up to the CCS, and their answer—1 May 1944—came back in mid-May, after being discussed at the next interallied conference in Washington, D.C. (TRIDENT).

At the Washington conference, the basic Casablanca priorities were restated. Under “Basic Undertakings in Support of Overall Strategic Concept,” there was listed, in conjunction with the use of the heavy bomber weapon in what was named the Combined Bomber Offensive, the resolution “that forces and equipment shall be established in the United Kingdom with the object of mounting an operation with a target date of 1 May 1944 to secure a lodgment on the Continent from which further offensive operations can be carried out.”41 This was far short of being an ironclad commitment to a cross-Channel assault. It was still just one available option of many, but it did allow Morgan to move forward.

The Combined Chiefs noted in their response to Morgan that his report was to be considered at the Quebec Conference (QUADRANT) in mid-August. Working backward from that date, the CCS would need to have the outline plan for both the cross-Channel assault and the “return to the Continent in case of German disintegration” by 1 August to allow time for them to consider the recommendations. Following from that, the due date to the British COS would be 15 July—Morgan reported to the Combined Chiefs who had authorized the staff, but through the British COS, his immediate superiors, who therefore had a right of first veto on any proposal.

While waiting for the official directive formally appointing him, Morgan knew he had the choice of either waiting for the paperwork to arrive or to “indulge in intense activity guided by common sense and one’s personal predilections.”42 He chose the latter course. He found an unoccupied room in Norfolk House, which was a modern, purpose-built office building, and talked the management into assigning it to him. It happened to be the room where he first met Eisenhower. He also prevailed upon the various organizations located in Norfolk House to provide him with clerical help when needed. At this point his staff consisted of “Bobbie, my aide-de-camp; my motor driver, Corporal Bainbridge, whom together with his car I had frankly stolen from 1st Corps headquarters; and two batmen [personal orderlies].”43 Morgan would readily confess to a weakness for the unconventional, and this new assignment was certainly beginning in a most unconventional way.

Morgan was summoned to a lunch at Chequers on 4 April so that Churchill could take the measure of the man. The prime minister showed his guests the film Desert Victory and insisted that this demonstrated the way to defeat the Germans. Morgan demurred, noting that while war in the African desert and war in northwest Europe may have things in common, there were also certain differences to be considered. Churchill let the comment pass and notified the War Office that Morgan “would do.”

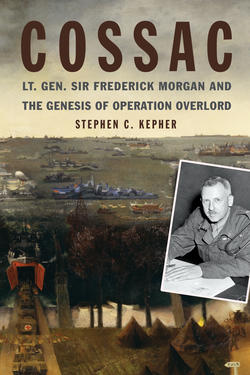

In his room at the Mount Royal Hotel one evening during this period, Morgan gave thought to his new situation as he took his bath. His new title was unwieldy; those with whom he was to work and to lead needed to be motivated and to sense that there was real change. This group would clearly need the creation of some esprit de corps. One element that would help would be a name that would unify the small band that was to be formed. It needed to have a martial sound yet needed to be vague enough that no one would be able to figure out what the job was by the name alone. His mid-bath inspiration was to title himself and his group COSSAC (Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Commander). And so COSSAC he became.