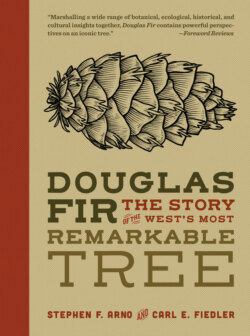

Читать книгу Douglas Fir - Stephen F. Arno - Страница 8

INTRODUCTION: Nature’s All-Purpose Tree

ОглавлениеMost westerners familiar with native forests probably think they know the Douglas-fir, which is after all one of our most common trees, indigenous to all the western states, western Canada, and the high mountains in Mexico.

However, few people realize the many forms and strategies Douglas-fir adopts to occupy more kinds of habitats than any other American tree. The species comprises two varieties—coastal Douglas-fir and inland, or Rocky Mountain, Douglas-fir—and includes the giants of the coastal forest, luxuriant conical trees in young stands, stout old sentinels along grassy ridges, and wind-sculpted dwarfs clinging to high mountain slopes. Douglas-fir occupies both damp habitats, such as ravines and north-facing slopes, and droughty ones, such as south-facing slopes, and nearly all sites between.

In moist environments, coastal Douglas-fir is a pioneer species— one that depends on fires, logging, and other major disturbances to create the open conditions that allow it to establish and avoid stifling competition from shade-tolerant species like western hemlock and Sitka spruce. These shade-tolerant species, unlike coastal Douglas-fir, can produce abundant saplings beneath the mature tree canopy and eventually form thickets of young trees that, without another disturbance, gradually replace aging Douglas-firs and take over the forest in perpetuity.

Douglas-fir also inhabits some of the hottest environments, such as sunbaked rocky islands in Washington’s San Juan archipelago, and the coldest ones that any trees can tolerate, including subalpine forests along the Continental Divide in Montana and Wyoming.

Both coastal and inland Douglas-fir are exceptionally resilient and quick to colonize following disturbances such as wildfire, logging, land clearing, and even residential developments, where it may later appear as a beautiful volunteer in a suburban yard. In the drier, fire-dependent forests of the interior West, some people view inland Douglas-fir as a sort of uncontrollable noxious weed, even though human efforts to eliminate fire are largely responsible for its proliferation. In inhospitable environments, Douglas-fir alone forms the native forest whether there are disturbances or not, such as in the high semi-arid mountains of southwestern Montana and southeastern Idaho, where the inland variety is the only erect tree. To sum up its adaptability, Douglas-fir is nature’s all-purpose tree.

Douglas-fir has proved valuable to humans as well, beginning with the many native peoples of North America who have lived among and used these trees for millennia. The species has long had a reputation for producing good lumber and firewood, and native people have used it in numerous other ways, such as for making tools and preparing medicines (see chapter 5).

Coastal Douglas-fir formed the foundation for early development and commerce by Euro-American settlers in the Pacific Northwest, where a few hundred sailing ships overloaded with Douglas-fir lumber were dispatched to distant ports each year in the mid and late nineteenth century (see chapter 4). Douglas-fir continues to yield more high-quality construction lumber than any other tree in the world, and because of its superior wood qualities, it has been cultivated for timber products on six of the seven continents.

Paradoxically, long after it became the world’s premier construction lumber, the tree’s botanical identity and common and scientific names remained in dispute because its cones and foliage were very different from any other known species at the time. And its common name continues to confound because, as described in chapter 1, Douglas-fir is actually not a true fir.

As a research forester for the US Forest Service, I (Stephen Arno) have worked and lived among a variety of native Douglas-fir forests from the Pacific Coast to the east slope of the Rocky Mountains for more than half a century. Continually amazed at this species’ ubiquity, resilience, and usefulness to humans, I wanted to present a comprehensive profile of this world-renowned but underappreciated tree. I have collaborated with Carl Fiedler on other forestry-related books and journal articles, greatly benefiting from his contributions, so I was delighted when he agreed to join me in writing the book you now hold.

I first became aware of Douglas-fir as a five-year-old living on Bainbridge Island, which is nestled in Puget Sound near Seattle, Washington. My first paying job was to carry slabs of thick Douglas-fir bark that drifted onto the beach up a tall wooden staircase to supply my mother with her favorite fuel for the kitchen stove. The slabs would break loose from old-growth logs banging against each other in booms (floating masses of saw logs encircled by a string of logs chained together end to end) that tugboats towed from place to place.

Douglas-fir was by far the most familiar tree of my childhood. Over a period of a few years in the mid to late 1940s, my whole family helped my father excavate a massive old-growth Douglas-fir stump that crowded our driveway. Dad used saltpeter to speed up rot, and laboriously dug out and then chopped and hand-sawed through the huge roots. Finally he managed to jack the stump loose. Next he hired a neighbor with a World War II surplus duck, a six-wheeldrive amphibious landing craft, to pull the monster out of its pit and drag it out of the way. It then served me and my friends as a 7-foottall jungle gym.

Later as an outdoorsy youngster, my stomping ground was on the nearby Kitsap Peninsula, on the west side of Puget Sound. The land had been scoured and compacted by an immense glacier during the last ice age, and as a result was largely covered with poor soils. Nevertheless, I observed in wonder that in most places, stumps from the original Douglas-fir forest, which had been logged a half century earlier, were commonly 4 feet or more in diameter.

Wherever the original forest had been spared, it was dominated by craggy-barked Douglas-firs 4 to 8 feet thick and commonly more than 200 feet tall. Logging and sawmills were the mainstay of the rural economy in western Washington, and I learned that the Puget Sound mills had once loaded sailing ships with Douglas-fir lumber bound for San Francisco and other port cities. I also learned that in 1871 my grandfather, then six years old, and his extended family had sailed stormy seas from San Francisco to Puget Sound on the return voyage of a lumber schooner. According to my aunt’s historical account, grandpa was the only family member who didn’t get seasick and was thus able to help the crew and his family with chores.

We moved to the outskirts of Bremerton on the Kitsap Peninsula in 1950. My parents bought a small house on about 120 feet of low-bank waterfront, which was inexpensive then. When one of us spotted a log from our front window floating by in the swift current, I hustled out in my 11-foot boat, tied a rope around it, and towed it to our beach. Then I cut the log up for firewood using our 6-foot crosscut saw. Known to old-time loggers as “misery whips,” this type of saw had been used for well over a century. Douglas-fir provided the best all-around firewood, so we used little else to heat our house.

As I got older, I noticed that Douglas-fir grew almost everywhere, including on the parched rock outcrops in the rain-shadow zone northeast of the Olympic Mountains as well as in the Olympic Rain Forest, and among subalpine meadows atop mile-high Hurricane Ridge in Olympic National Park. I’ll never forget the godsend provided by a big old Douglas-fir growing amid the cliffs of a river gorge in southeastern Olympic National Park. Just out of high school in 1961, two friends and I lost the little-used, partly snow-covered route leading from a high-country ridge down thousands of feet to a safe crossing of the North Fork Skokomish River. We had unwittingly descended in the wrong direction for hours down steep, stony slopes. It was nearing nightfall when we reached the bottom and beheld a frightening sight—a rock-walled gorge containing the roaring river swollen with snowmelt. How could we possibly cross it to get to the trailhead a mile away in dense, untracked forest on the other side, where our parents were waiting?

Finding a safe crossing of this abyss was nearly impossible. We faced the probability that a search party would be called out at dawn and that we would have to backtrack several thousand feet up the steep, brushy slopes with full packs to regain the ridgetop, find the correct route, and then descend to our intended river crossing. Worse yet, there wasn’t even a semi-flat spot for an overnight bivouac. Praying for a miracle, I climbed around a corner in the gorge and beheld an unbelievable sight: a 4-foot-thick Douglas-fir growing out of the cliffs had uprooted and lay level straight across the chasm. We had never so appreciated a tree.

In the summer of 1962, I worked at a log-scaling station in the North Cascades. Log trucks brought in huge virgin Douglas-firs from the surrounding forest. Occasionally a truck’s 30-ton load consisted of just three massive logs from a single tree, even though these giants had been harvested from steep, rocky mountainsides. Large granite boulders were sometimes jammed into a big log, testifying to the cliffs it had crashed down from. One day a log truck driver let me ride with him up to the logging site carved into granite cliffs. Big Douglas-firs grew wherever there was a patch of soil. Even as an energetic and agile young man, I couldn’t imagine how the fallers climbed those treacherous heights with big chain saws and worked there for many hours each day. The guys who measured, limbed, and bucked the logs into the lengths specified by the sawmills didn’t have it easy either. Logging in steep terrain was obviously dangerous business.

Later, as a seasonal naturalist in Olympic National Park, I studied some of the gigantic Douglas-firs scattered amid the Hoh River Rain Forest. South of the Hoh, I waded the Queets River to see the famous Queets Fir, which at more than 14 feet in diameter was the largest known Douglas-fir at that time.

The rain forest Douglas-firs were obviously ancient relicts gradually being replaced by younger western hemlock and Sitka spruce trees. I observed the aftermath of a few twentieth-century wildfires that had escaped suppression in the park’s mountain forests and saw that many big old Douglas-firs, with their thick, corky bark and lofty crowns, had survived, while associated hemlocks had nearly all died. Also, I noticed that the burned forests had regenerated young trees, especially Douglas-firs, and a rich assortment of fruit-bearing shrubs and herbaceous plants. These post-fire communities teemed with a variety of birds, some of which feed on Douglas-fir seeds, and other wildlife, including black bears, which like to strip and eat the inner bark of young Douglas-firs.

I moved to the inland Northwest in 1963 and then to the Northern Rockies for college and a career in forestry. Forests in these regions were often dominated by other long-lived trees, particularly ponderosa pine, western larch, and western white pine, each with its own unique majesty. Interestingly, inland Douglas-fir nearly always grew in these forests and often regenerated in abundance, filling the understory with saplings and young pole-size trees. Douglas-fir was clearly poised to dominate much of the inland forest.

In 1971, soon after completing a PhD in forest ecology, and keeping mum about that to coworkers in my first job in a sawmill and my second job as a timber-sale forester, I was blessed to be chosen as part of a small research team whose goal was to document examples of the original forest types in the Northern Rockies. We inventoried all trees and flowering plants in 1482 large plots within mature forest stands in Montana and described ecological conditions such as soils, geology, wildlife use, and evidence of past fires. It turned out that Douglas-fir occupied 998 of these stands—a far higher frequency than any other tree or plant. A similar inventory of forests in central Idaho accumulated a sample of 761 stands, 506 of which contained Douglas-fir, again the most frequently recorded plant. Douglas-fir is also widely present and often a dominant tree in forests from central British Columbia to central California and south through the Rockies to the high mountains of southern Arizona. And in all of these regions this species is often one of the biggest trees.

For many years I studied the fire history of old-growth Rocky Mountain forests, consisting of ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, and western larch. For many centuries, at least, frequent surface fires prevented the highly competitive Douglas-fir from gaining dominance by killing its saplings in far greater numbers than those of fire-resistant ponderosa pine and larch.

I also examined high mountain grasslands and adjacent dry forests dominated by Douglas-fir and lodgepole pine, including the 6500-foot Lamar Valley in Yellowstone National Park. This high, dry grassland environment with its relatively light snowfall serves as critical winter range for the area's elk, deer, and bison, and attracts predators and scavengers such as wolves, ravens, and eagles. Historically, frequent grass fires kept the surrounding forest at bay. Older Douglas-firs tend to be fire-resistant, and some trees at the edge of what used to be an open forest were four or five centuries old and had survived many fires. A few of them measured 4 to 5.5 feet in diameter. But starting early in the twentieth century, two factors allowed Douglas-fir saplings to colonize the Lamar Valley grasslands: fire suppression, and heavy grazing by a burgeoning elk herd that resulted from exterminating the elks’ primary native predator—wolves. Nearly a century later, despite the sparse grass fuel, the 1988 Yellowstone fires burned the surrounding and encroaching Douglas-fir forest more severely than most historic fires because of the accumulation of young Douglas-fir thickets and fallen tree limbs and snags.

After sixty years of observing both coastal and inland Douglas-fir and studying their ecology and historical importance, I feel passionate about sharing the story of this truly extraordinary tree. Books and scientific publications have not done full justice to the enormous role the two varieties of Douglas-fir have played in the lives of humans since first contact, nor to the trees’ preeminent stature and influence in western forests.

I(Carl) had a distinctly different introduction to Douglas-fir. My experiences started later in life, in a different place, and with the inland rather than the coastal variety. My interactions and perceptions relative to Douglas-fir also differ, but together our perspectives provide a broader and more nuanced story of this enigmatic western tree. Much like two blindfolded men grabbing the opposite ends of an elephant, our initial perceptions reflect our contact with an “elephant” in the plant kingdom that is so widely distributed and variable that it is better described and understood from more than one angle.

My first encounter with Douglas-fir didn’t come until I moved west for college, because it isn’t native to the Northwoods of Wisconsin where I grew up. I arrived at the University of Montana on a fall afternoon in 1967, hurried over to Main Hall to skim the job listings, and promptly landed part-time surveying work. I started my new job the next morning, and as an inquisitive newcomer, I queried my boss about the unfamiliar trees I saw along our drive to work. I felt somewhat betrayed when he identified several unimposing trees with gray bark and dark green needles as Douglas-firs. I had grown up seeing eye-catching Weyerhaeuser ads of coastal Douglas-fir forests in the 1950s, and frankly these trees didn’t measure up. Naively assuming that all Douglas-firs were the large kind, I was unaware of the smaller Rocky Mountain variety. I would later learn that despite their typically modest presence, inland Douglas-fir comprise an ecological time bomb across much of the Mountain West. Over the next fifty years, my work and travels along the backroads of the West would allow me to experience Douglas-fir in two Canadian provinces, eleven western states, Texas, and in virtually all of its native habitats. Seeing the species in its countless manifestations led me to conclude that Douglas-fir is truly the Jekyll and Hyde of the western forest, depending on the time, place, and variety (coastal or inland).

I was drafted by the Army in the summer of 1970 and sent to boot camp at Fort Lewis (now Joint Base Lewis-McChord), about 50 miles south of Seattle. While out on maneuvers one day, I was shocked to see the tops of scattered mature ponderosa pines poking above smaller coastal Douglas-fir. My dismay came from seeing ponderosa pine growing just off the shores of Puget Sound, where it seemingly didn’t belong. The much greater precipitation and higher humidity that characterized this coastal site contrasted sharply with the dry conditions where I typically saw ponderosa pine in the Rocky Mountains. Well-drained, rocky soils left behind by receding glaciers likely accounted for the pine’s occurrence in this unexpected place. Ironically, coastal Douglas-fir encroachment under the remnant Fort Lewis ponderosa pine presented a tiny, more advanced example of the region-wide phenomenon slowly unfolding in the dry interior West, where inland Douglas-fir had just begun to invade and crowd out the historically dominant ponderosa pine.

I spent the next nearly two years at Fort Ord along the central California coast, often traveling to Yosemite National Park for weekend hikes. It was in Yosemite that I observed Douglas-fir’s superior ability to thrive and grow large on what John Muir termed “earthquake talus,” slopes of large, nonstationary rocks at the base of cliffs. Although Yosemite marks the southernmost occurrence of coastal Douglas-fir in the Sierra, I saw occasional firs of surprising girth (5 feet in diameter and larger) on the Mist Trail, below Liberty Cap, and along the Panorama Trail.

A 1971 trip to meet a friend in nearby San Francisco included a visit to Muir Woods National Monument and a surprise encounter with Douglas-fir. Muir Woods, located just a few miles north of San Francisco, is a several-hundred-acre enclave of redwoods up to 1100 years old that escaped the first wave of early logging. The monument also boasts a few impressive Douglas-firs, the largest being the massive 280-foot Kent Tree, named after a US Congressman who donated land for the preserve. Despite growing in a redwood sanctuary, the big Douglas-fir was Kent’s favorite tree, measuring more than 20 feet taller than the tallest redwood in the park.

After completing military service in 1972, I worked out of a pickup camper as an itinerant research forester sampling regeneration in subalpine forests across the Mountain West. These sites ranged up to nearly 10,000 feet, which established the upper end of an astonishing elevational range for Douglas-firs when compared to the sea-level trees I had seen at Fort Lewis, and provided a real eyeopener for me.

Following graduate school, I took my first full-time job with the US Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station in 1980. It was my dream job—travel the interior West and identify broadscale ecological problems on national forestlands from the Canadian line to southern Utah. Field evaluations on dozens of national forests revealed several extensive ecological concerns. One pervasive condition involved thickets, or a layer, of small inland Douglas-fir developing under an overstory of ponderosa pine, ultimately resulting in Douglas-fir dominance and increased threats to stand health and survival. Perhaps because the bottom-up transformation of ponderosa forests to Douglas-fir would take decades to play out, station personnel chose to focus on several other pressing ecological problems at the time.

For this initial assignment, I traveled throughout a wide swath of the interior West, where I also observed Douglas-fir thriving in the dry, cold environments of “island” mountain ranges. Such ranges are typically separated from other mountain ranges and major forested areas by either semi-arid plains or high desert. I found that Douglas-fir often dominated these isolated, high-elevation mountains, where most of the forested zone was too cold for ponderosa pine and too dry for true firs, spruces, or aspen. On lower, less prominent islands, Douglas-fir often dominated at even the highest elevations.

Years later while a forestry professor at the University of Montana, I combed the state’s island mountain ranges looking for suitable areas for a graduate student research project. Over previous decades I had hiked much of the Missouri River Breaks and similar topography along several smaller river systems in north-central and eastern Montana. On rare occasions, I found small individual Douglas-fir trees growing in unexpected places. Their presence on these harsh outlier sites was surprising—far beyond the known easternmost populations of Douglas-fir that grow in central Montana’s island mountain ranges. None of the few Douglas-firs I observed were anywhere close to maturity compared to nearby larger ponderosa pines, suggesting that fire kills the majority of these trees while they are still small and more vulnerable to fire than the pines. It also suggests that wind-driven fire rather than lack of water prevents these trees from developing to seed-bearing size. Though the casual observer could easily surmise that Douglas-fir is entirely absent from the eastern Montana landscape, time spent poking around these highly eroded river breaks and coulees may reveal a rare find—a small Douglas-fir growing in a moist microsite, perhaps fed by seepage from an underground spring, but likely surviving only until the next wildfire.

Extensive traveling over the years further sparked my curiosity to visit some of the West’s little-known national forests and out-of-the-way national parks and monuments. One such trip included a stop at El Malpais National Monument in western New Mexico, where I was fascinated by the dwarf Douglas-firs clinging to life on nearly barren lava flows. Many of the stunted trees were centuries old but little more than head height. Recalling my earlier visit to Muir Woods, I was struck by the vast differences in growing conditions at El Malpais, yet Douglas-fir were able to grow to old age in both environments. And though both the massive Kent Tree and these elfin Douglas-firs were more than five hundred years old, the giant at Muir Woods was larger in diameter than some of the lava-flow trees were tall and had more than a thousand times the cubic volume. No other tree species on the planet displays such mind-bending contrasts in mature tree size. It is this extraordinary diversity that makes Douglas-fir such an intriguing species, richly deserving of deeper inquiry and broader exposure of its colorful history.

Steve Arno’s deep ecological knowledge and experience with both varieties of Douglas-fir, coupled with our history of coauthoring two previous books, provided a strong incentive for me to join him in documenting the life story of this remarkable tree. Readers will find that Douglas-fir is indeed nature’s all-purpose tree. It has provided more wood than any other species for building the infrastructure of the American West; its exceptional genetic diversity allows it to have a wider geographic distribution than any other North American conifer; its unique and puzzling combination of characteristics prevented taxonomists from selecting an appropriate scientific name for 150 years; and its longevity and distinct annual rings have allowed scientists to estimate relationships between growth and precipitation extending back more than two thousand years. Finally, before the largest individuals were removed in the early days of logging, historical reports offer substantial anecdotal evidence that coastal Douglas-fir may have been the tallest trees in the world—taller even than redwoods.