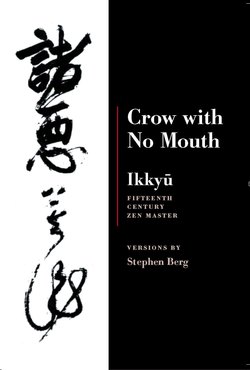

Читать книгу Ikkyu: Crow With No Mouth - Stephen Berg - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

When Ninagawa-Shinzaemon, linked verse poet and Zen devotee, heard that Ikkyū, abbot of the famous Daitokuji in Murasakino (violet field) of Kyoto, was a remarkable master, he desired to become his disciple. He called on Ikkyū, and the following dialogue took place at the temple entrance:

Ikkyū: Who are you?

Ninagawa: A devotee of Buddhism.

Ikkyū: You are from?

Ninagawa: Your region.

Ikkyū: Ah. And what’s happening there these days?

Ninagawa: The crows caw, the sparrows twitter.

Ikkyū: And where do you think you are now?

Ninagawa: In a field dyed violet.

Ikkyū: Why?

Ninagawa: Miscanthus, morning glories, safflowers, chrysanthemums, asters.

Ikkyū: And after they’re gone?

Ninagawa: It’s Miyagino (field known for its autumn flowering).

Ikkyū: What happens in the field?

Ninagawa: The stream flows through, the wind sweeps over.

Amazed at Ninagawa’s Zen-like speech, Ikkyū led him to his room and served him tea. Then he spoke the following impromptu verse:

I want to serve

You delicacies.

Alas! the Zen sect

Can offer nothing.

At which the visitor replied:

The mind which treats me

To nothing is the original void—

A delicacy of delicacies.

Deeply moved, the master said, “My son, you have learned much.”

Speaking those words, perhaps Ikkyū recalled harsh treatment he received from his second master, Kasō Sōdon, in the very same circumstances. Kasō had ignored him completely while he waited five days outside his temple gate, then had disciples pour water over his head. It would have taken much more to discourage this would-be disciple. Finally Kasō agreed to take him on. It could not have been his kindly disposition that encouraged Ninagawa to approach Ikkyū, whose reputation was fierce. Rather all he heard of the great master, famed painter and poet, suggested such an approach might please Ikkyū, which proved to be the case for the fortunate Ninagawa.

Ikkyū Sōjun, according to traditional sources, was born in 1394, the natural child of the Emperor Go Komatsu and a favorite lady in waiting, of the Fujiwara clan, at the Kyoto court. The Empress, seething, it’s told, had her banished to a low section of the city, where Ikkyū was born. At six the boy was sent for training to Kyoto’s Ankokuji Temple. Precocious, by thirteen he was composing poems in Chinese, a poem, no less, daily. At fifteen he wrote lines that were recited everywhere. He was already extremely independent, something of a gadfly. There was much that bothered him about temple life, its pious snobbery over family connections, and he nettled fellow monks with his sharp comments.

By seventeen Ikkyū had a Zen master, Ken’ō, with whom he lived for four years, until Ken’ō’s death. Ken’ō was known for modesty and compassionate concern for the welfare of his disciples, and his loss affected Ikkyū profoundly. In comparison with Ken’ō, other Zen masters seemed ridiculously ostentations and, in matters of temple ritual, nitpicking. Seeking another master, Ikkyū chose a severe disciplinarian of the Rinzai sect named Kasō Sōdon. He was of the Daitokuji Temple line, whose distinguished lineage led to Hakuin (1686–1769), among its greatest heirs. While Kasō was aware of the importance of such lineage, and performed his abbot’s duties faithfully, he preferred living in a small temple in Kataka, a short distance from Kyoto on the shore of Lake Biwa.

When twenty-five, Ikkyū, hearing a song from the Heike Monogatari, suddenly penetrated a koan (Zen problem for meditation) given him by Kasō, and he always was to speak of the moment as his first kenshō (awakening). But a more profound experience came two years later. While meditating in a boat on Lake Biwa, hearing a crow call, he was immediately, fully enlightened.

He hurried to Kasō for approval of his satori, but the master said, “This is the enlightenment of a mere arhat, you’re no master yet.” Ikkyū replied, “Then I’m happy to be an arhat, I detest masters.” At which Kasō declared, “Ha, now you really are a master.”

After his awakening Ikkyū stayed with the master, taking care of him in growing illness, a paralysis of the lower limbs that necessitated his being carried everywhere. Ikkyū’s unflagging loyalty impressed all, became legendary:

my dying teacher could not wipe himself unlike you disciples

who use bamboo I cleaned his lovely ass with my bare hands

Kasō died when Ikkyū was thirty-five, and the bereaved monk, who at the darkest moment of mourning had been close to suicide, began an endless round of travel, lasting the remainder of his life. He could not settle anywhere, and his behavior, even in those bawdy times, was thought scandalous. He never pretended to be saintly, took his passions as a natural part of life, frankly loved sake and women. After a disappointing day he would rush from the temple to a bar, wind up at a brothel. After which there was often a crisis of self-doubt, if not guilt. At such moments he went to his hermitage in the mountains at Joo:

ten years of whorehouse joy I’m alone now in the mountains

the pines are like a jail the wind scratches my skin

Ikkyū also had a hermitage in Kyoto which he called Katsuroan (Blind Donkey Hermitage), and often stayed at Daitokuji. But increasingly, to the point of anguish, he became disgusted with worldly carryings on at the main temple, shuddered at the business side of its affairs, and felt intense enmity toward Kasō’s successor, Yōsō. Twenty years his senior, Yōsō represented all Ikkyū despised in Rinzai practices of the day, among them frantic hustling for donations:

Yōsō hangs up ladles baskets useless donations in the temple

my style’s a straw raincoat strolls by rivers and lakes

......................................................

ten fussy days running this temple all red tape

look me up if you want to in the bar whorehouse fish market

In 1471, when seventy-seven, Ikkyū revealed his passion for a blind girl, an attendant at the Shūon’an Temple at Takigi. He wrote poems about their affair, some farcical, some very moving. He was self-conscious at the oddness of an old Zen monk falling for a young woman, but they spent years together, Ikkyū’s feeling for her growing in intensity:

I love taking my new girl blind Mori on a spring picnic

I love seeing her exquisite free face its moist sexual heat shine

...............................................................

your name Mori means forest like the infinite fresh

green distances of your blindness

When Ikkyū reached the age of eighty-two, far steadier, much becalmed, he was made abbot of Daitokuji, and often expressed childlike wonderment at his elevation, given his unorthodox behavior throughout his long life, to a position so lofty. Though he appeared to revel in his unexpected role, he was often away from Daitokuji, mostly at his beloved Shūon’an Temple where he died in 1482, at eighty-eight.

While it may be that Ikkyū is best known in the Zen world as a sort of rake, always spitting in the face of orthodoxy, madly carrying on as freest of the free, most of his poems are concerned with Zen, revered to this day by Zennists. Among the best-known of such poems are two based on the concepts “Void in Form” and “Form in Void” as given in the Hridaya (Heart Sutra), one of the major sutras of Buddhism and of great importance to the Zen sect:

VOID IN FORM

When, just as they are,

White dewdrops gather

On scarlet maple leaves,

Regard the scarlet beads!

..........................

FORM IN VOID

The tree is stripped,

All color, fragrance gone,

Yet already on the bough,

Uncaring spring!