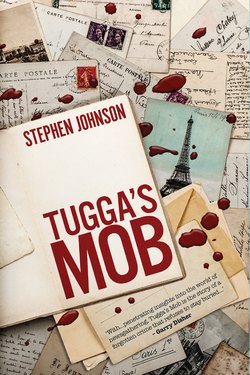

Читать книгу Tugga's Mob - Stephen Johnson - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 4

ОглавлениеAndrew Hackett found himself back in his home office at 5.50pm – earlier than he anticipated. Saturday afternoon drinks with Ferdy Ackermann and his latest beau Jacinta, hadn’t gone well, at least not for the ladies. The men had been best mates since kindergarten and nothing could break their bond.

Hackett’s wife was a supremely tolerant person, capable of making herself comfortable in any social gathering. She’d even left one former Prime Minister besotted with her charms at a Liberal Party fundraiser before the last election. But, two hours with Ferdy’s latest conquest was too challenging even for Marianne.

The men had been engrossed in conversation – as per usual, leaving the ladies to entertain themselves – until the harsh scrape of a metal chair on concrete indicated things had gone awry. Hackett realised his wife was on her feet glaring at Jacinta.

‘Andrew, take me home please before I do the world a favour and throttle this gold-digger.’

Marianne picked up her handbag and left their kerbside table across the road from the Botanical Gardens. As Ferdy’s lady-friend was a regular face on the South Yarra social scene it ensured Marianne’s parting zinger, heard by several tables of drinkers, would emerge on Twitter before Marianne reached the BMW.

‘Jacinta clawed in cat-fight at the gardens!’

Hackett shrugged at Ferdy and hastily chased after his wife. He didn’t feel any need to apologise to Jacinta, they hadn’t said anything more than hello. His best mate had been squiring ladies of a similar ilk – tall, model-thin and many years his junior – ever since Ferdy accumulated the first of his many millions.

Hackett always compared Ferdy to the debonair British actor Sir Roger Moore in his prime. Unlike the James Bond heart-throb, Ferdy never endangered his playboy lifestyle by getting married. Most lady friends were accepted by Marianne for the duration of the romance which was usually weeks and, occasionally, a couple of months.

Hackett caught up with his furious wife at their car. He opened the passenger door and looked back to see Ferdy pouring more champagne. Last drinks for Jacinta? Marianne’s only comment on the five-minute drive home was to declare that Jacinta was never to set foot in her house, and that Ferdy had some serious grovelling to make up for that social faux pas.

Hackett knew Marianne would eventually tell him the reason for her explosive exit. They had been few and far between in their 27- year marriage; or so he believed when he wasn’t the cause of them. After storming around the home, tidying benches and rearranging cushions on sofas that didn’t need attention, Marianne, still clutching a cushion, finally entered the office to release the pressure valve.

‘Do you know what that silly cow said?’

‘No, babe,’ Hackett patiently replied, knowing it wouldn’t have been wise to guess.

‘After two hours of her twittering on about her social life and trying to get me to tell her how rich Ferdy is, she says she’s off to Thailand for another boob and face job which, incidentally, she expects Ferdy to pay for. And then she suggested I might like to join her at the clinic. Get my boobs done. What a cheek! Does she want a group discount for Ferdy?’

‘Ahhhh.’ Hackett slowly nodded as the chair reclined, considering the best way to calm his wife. Marianne wasn’t a vain or shallow woman. But turning 50 had made her a tad more conscious of her body which, in Hackett’s opinion, was still sensational. Three sessions a week at the gym, regular squash matches, yoga, the occasional tennis game and annual visits to top-class spas ensured the attractive brunette could still turn heads in Toorak. However, Hackett knew that Marianne was sensitive about the size of her bust. For Jacinta to suggest Marianne should consider breast enhancement was more dangerous than playing with a hand grenade.

‘What a stupid bitch.’ Hackett assumed much of the steam had been vented. ‘I don’t know where Ferdy finds trash like that. Anyway, I’d never let those amateur-choppers touch your tits – I’d only send you to be the best Swiss surgical clinics. Maybe they could fill them with milk chocolate?’

Marianne’s eyes widened and her nostrils flared after a sharp intake of breath. She held the indignant pose for several seconds, but it was a waste of time. She couldn’t outplay her husband’s poker face. She giggled and threw the cushion at him.

‘You selfish bastard.’ Marianne launched herself into Hackett’s lap, almost tipping over the chair. ‘Always thinking of your stomach. I’d make them put soy milk in. At least you might get something healthy for a change.’

Hackett playfully cupped a breast as they cuddled. ‘You know I love you just the way you are, babe. Jacinta is held together by silicone. Give me the real thing any day – and chocolate milk?’ They laughed. Hackett’s gamble had worked and Marianne’s insecurities were tucked away.

‘I reckon Ferdy’s already trawling through his date book for a new dinner companion. And speaking of food, I have a couple of things to check before I fire up the barbie for those steaks.’

That was Marianne’s cue to exit and start dinner preparations. Cucumbers, courgettes, lettuce, broccoli and other healthy options would be chopped, cooked and served. Hackett would brush them aside, as usual. His wife had been trying to change his eating habits from rare steaks and potatoes ever since he turned 50. She would also regularly poke his middle-age paunch. The demands of the television job had restricted his gym visits to a couple of days a month, while the golf games were down to one a fortnight. Hackett believed he was still a healthy man and he would return to a stricter exercise regime once the AFL rights business was sorted.

He had a few minutes until the opening titles of the news, so Hackett listened to O’Malley’s urgent voice mail. To be fair Hackett gave it due diligence, listing the salient points for himself – extra chopper, extra camera, possibly an extra reporter. That was several thousand dollars he saved the company by not answering the phone earlier. And what would be the result if he had granted their wishes? One minute and 20 seconds of breathless reporting by a young Communications Studies graduate on a story that would be forgotten by the first commercial break?

Hackett barely registered the story was about a car crash on the Great Ocean Road. His priority was the cost. Nevertheless, it was almost six o’clock, so he thought he would justify his decision by viewing whatever the news department had scrambled together.

I’ll text O’Malley later, tell him it would’ve been wasted money anyway.

He reached for the remote and switched on the new Samsung 4K television that dominated the wall opposite his desk – paid for by the station, naturally. He swung the chair around and settled in for what he expected to be a few minutes of typical weekend news coverage: another horror road smash.

Hackett nudged up the volume. The first pictures looked like mobile phone video of a vehicle pancaked on rocks. Why are they begging for extra choppers and cameras? Those pictures tell the story.

Any minor pangs of conscience were forgotten as Hackett listened to the story unfold. An Aireys Inlet publican stopped a drunk from driving to his beach house, the idiot waited until the pub closed and used a spare key to resume the journey, but a few kms later drove over a cliff near Lorne. The story looked to be compiled mostly from a mobile phone, the pictures were wobbly and the sound was distorted. The aerials were the steadiest images and better illustrated the driver’s death plunge from the layby. Silly bastard.

Hackett reached for the remote to switch the TV off when a photo of the victim appeared on screen. He froze.

Fuck me! Tugga?

Kevin Tancred. The victim’s name at the top of the story did not ring any bells. Hackett probably never heard him called Kevin in the weeks they spent together all those years ago. He was simply known as Tugga. Hackett paused the TV on the driver’s licence image. Three decades older than the last time Hackett had seen the big fella, and the face was more weathered and carrying heavy bags under the eyes, but there was no doubt: that’s definitely Tugga.

When did you move here and why were you cliff-diving at Lorne?

A personal connection gave Hackett a reason to find out more about the story. He pressed rewind on the remote so that he could listen properly to the script. He learned that Tugga was an expat Kiwi landscaper who moved to Geelong in the late ’80s. He built a thriving business, which enabled him to create a luxurious beach house at Apollo Bay where he spent most weekends. He was well known in most of the bars along the coast – a euphemism for being a heavy drinker – and was occasionally known to be belligerent.

Most of that stacked up with the Tugga that Hackett knew. He loved his booze and could be boisterous if he drank too much. The “famous landscaper” profession was a few steps up from when Tugga and his two mates left New Zealand for their Overseas Experience. Hackett remembered the big fella earned his travel money chopping trees in North Island forests.

Did you make it good Tugga, or is someone using journalistic licence?

Hackett paused the TV again on the photo of Tugga, mentally reconstructing the real-life Tugga that he once knew. Tugga was more than two metres tall, with muscular arms and legs, broad shoulders and a chest that could have stopped a bus. The massive frame was topped by thick dark hair and a drooping moustache which made Tugga Tancred hard to forget. Hackett recalled the man bragging he had been a promising rugby player, a prop, who lost any chance of being an All Black because of a youthful indiscretion. Hackett never learned what that sin was. He also recalled Tugga’s dimples. When employed, they softened the physical impression of a bear in a man’s clothing and helped Tugga portray a boyish charm that made most people comfortable in his presence. Or, at least, that they weren’t going to be torn limb from limb as long as the big fella was smiling. Sadly, Hackett couldn’t find any signs of the younger Tugga, or the dimples, in the photo on his TV.

He looks…haunted?

Hackett found himself, for the first time, wanting more from his station’s news service. Tugga’s demise was a surprise, naturally. He’d lost friends and family over the years to illness and accidents; had experienced all the emotions, or so he thought.

But Tugga’s death was unsettling for some reason. They had known each other for seven weeks in the mid ’80s, meeting as members of a tour group travelling through Europe on a coach/ camping expedition. It was a fun and memorable adventure, literally sowing wild oats as most of the bus group partied from London to Istanbul, and back again.

Hackett had been 25 at the time, a few years out of university and yet to settle properly into an accountancy career. Ferdy, always more focused than Hackett at that age, had pulled out of the Europe tour at the last minute because of a business opportunity that came up in London before the trip began. Hackett had a thirst for excitement and girls, plus it didn’t make sense to travel all the way to Europe and not see the most famous attractions. He met dozens of Aussies and Kiwis in London, mostly working in pubs, who never did more than travel to the running of the bulls in Spain and the Oktoberfest in Munich. Many couldn’t afford much more, Hackett remembered. Pay rates in London were so low and the cost of living was astronomical. Although, even Hackett the fledgling accountant, thought some common sense and planning would have been beneficial for a lot of travellers in those days.

The news program continued, largely ignored now by Hackett as faces, cities and sights filtered through his memory. His eyes drifted from the television to what Marianne called his brag wall. It was filled with pictures of him with famous business people, politicians, sports stars, celebrities and the obligatory family photographs. Mostly the wall was full of people who would not have given him a second glance 30 years ago when he was a carefree tourist in Europe.

More personal mementos from his travels were tucked into a small alcove in the corner. From a distance, a white Major League baseball, signed by a Hall of Fame member, initially caught his attention.

Then there was the plastic cube containing a slim and dark piece of metal: a spent Turkish cartridge from Gallipoli. Hackett hadn’t found it. One of the other passengers, Brian, returned to the camp site with his trophy after their day exploring the famous First World War battle sites: ANZAC Cove, Plugge’s Plateau, Lone Pine, Chunuk Bair, Quinn’s Post and many others.

They’d been nothing but names in school history books until that emotional experience of walking in the footsteps of the ANZACs 71 years later.

Hackett remembered Brian showing the dirt-filled 7.66 x 53 mm cartridge, with Arabic script and Islamic crescent at the base, to a hushed group. Everyone wondered if the business end had claimed an Australian or New Zealand life. Hackett offered Brian a six pack of Efes beer for the prized memento, but was rejected. A week later Hackett spotted it rolling around on the bus floor near Brian’s gear, so he tucked it away in his own backpack.

Hackett’s eyes rested upon another unframed picture at the back of the alcove, a group photo of young people wearing traditional Dutch costumes. It was taken in Volendam, a quaint fishing port north of Amsterdam. The visit and photo were a standard part of most tourist itineraries and was, in their case, in the final days of the journey. The tour started with a clog-making demonstration followed by cheese-tasting and small donuts with a sweet syrup. Then it was time to play dress-up with everyone in clogs, the girls in pointed bonnets, flowing dresses and long aprons. Most of the men donned dark jackets, trousers and caps, although there were always a few who swapped genders when a fun photo opportunity arose.

Hackett walked over to the alcove and picked up the photo. There he was frozen in time – 30 years younger with more hair and a Tom Selleck moustache that Marianne insisted he remove before their wedding a few years later.

Hackett was standing in the back row, one away from the now dead Tugga Tancred. In between was one of Tugga’s New Zealand mates, Drew. On the other side was Gerry. Beside him, Helen, another Kiwi friend who followed the trio from Sydney to England for the Big OE. The photo brought so much back in a flash.

Tugga’s Mob! That’s what the other passengers on the trip called Tugga’s mates. They were the biggest, loudest, booziest and, much of the time, most enjoyable group on the tour. They were the first into the campsite bars and usually the last to leave. Hackett had no natural connection with the Kiwis: no career, sporting, cultural or national affiliations. The only common ground was wanting to have a good time while seeing what Europe had to offer.

The Kiwis were big men, close to two metres, with Tugga still towering over everyone. Hackett was similar in height to Drew and Gerry but couldn’t match their muscle mass, theirs being the product of several years felling trees. They had a shared interest in beer, and anything else alcoholic the Europeans could offer, and that was enough to bond them for seven weeks in 1986. So much so that, according to the other passengers, Hackett was one of Tugga’s Mob for the duration of the tour.

Hackett’s thoughts turned to the three surviving members of Tugga’s Mob but were interrupted by Marianne, urging him to fire up the barbecue. He placed the Volendam picture face-down on his desk, saw the faded writing on the back and recalled how most passengers had written their names and addresses on that final group photo on the last day of the trip.

Hackett’s curiosity about them and the other members of Tugga’s Mob stirred for the first time in many years.

A Google search later might be interesting.

Hackett picked up his mobile and tapped out a text to O’Malley. He apologised for missing the earlier message, and told the COS they’d done a good job in the circumstances. Almost as an afterthought, he added that he knew the victim 30 years ago when travelling in Europe. Hackett wasn’t sure why he mentioned his connection to Tugga to the news crew. He didn’t think there’d be any more legs in the story; it looked like a straightforward case of drink-driving and falling asleep at the wheel. Was he trying to give himself more credibility with the lower ranks, show that he was more than The Hatchet? That he was human after all? The thought didn’t linger. It was discarded along with the phone as he headed for the courtyard and a couple of marinated steaks.