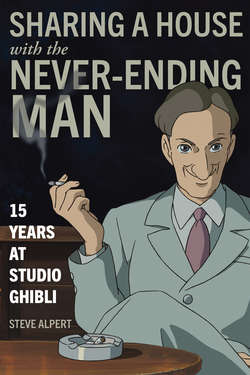

Читать книгу Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man - Steve Alpert - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Salaryman

Fools Rush In

I had been working in Tokyo for ten years, most recently at the Walt Disney Company, when Toshio Suzuki, the head of Studio Ghibli and the producer of nearly all of its films, hired me to start up the international division of Studio Ghibli and its parent company, Tokuma Shoten. With few exceptions, Ghibli’s films hadn’t been released outside of Japan. Suzuki thought it was time Ghibli’s films got the international audience they deserved.

But Studio Ghibli had its own nonconventional way of doing things. This was both the reason for its success in Japan and its inability to get its films screened outside of Japan. Suzuki needed a gaijin for his new international division. But he needed more than a gaijin with the appropriate business talents and experience. He needed a gaijin who could appreciate the subtleties of the way Ghibli/Tokuma functioned. I was a graduate student in Japanese literature before I switched to an MBA program, so I fit the bill. Theoretically.

Suzuki was concerned that even a Japanese-speaking gaijin might not be able to function in the pure and thoroughly Japanese environment that was Ghibli/Tokuma. He went to great lengths to insure that my transition to the new company would be smooth. To begin with he established my new division as a completely independent company within the Tokuma Group. The new company was called Tokuma International. Hayao Miyazaki designed our business cards. The logo was an image of Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the chairman of the Tokuma Group, sprouting wings and flying, presumably, out of Japan.

Suzuki at that time seemed to me to be both the busiest person and the person with the most free time on his hands of anyone I had ever met. This, as I would later learn, is what it’s like to be in the movie business.

Suzuki was based at Studio Ghibli in Higashi Koganei on the western outskirts of Tokyo. He ran the operational side of the studio while also keeping the production of the film on schedule and creatively on track. He provided support and a shoulder to lean on for the film’s director, Hayao Miyazaki, and he was the person to whom Miyazaki would turn in order to bounce ideas off of. Every time Miyazaki conceived a possible ending for his film, he would seek out Suzuki to get his reaction. If Suzuki approved right away, Miyazaki would discard the idea and begin again.

In addition to his duties at Ghibli, Suzuki was also the number-two man at Tokuma Shoten, a company that had businesses in publishing, movies, music, and computer games. His boss and mentor, Yasuyoshi Tokuma, chairman and sole owner of the parent company, was in his early seventies and had a penchant for causing trouble and creating situations. It was often Suzuki’s job to unravel the problems his boss had caused. This generally involved many time-consuming meetings and private, in-person visits.

Suzuki lived in central Tokyo and would start his day with a one-hour-plus drive out to Ghibli in suburban Koganei. He would work there for several hours, then drive back into central Tokyo to attend a meeting or meetings in Shinbashi, where Tokuma Shoten was located. Most meetings in Tokyo were followed by a side meeting, or meetings, in a coffee shop or restaurant. Then Suzuki would drive back again to Ghibli to see how Mononoke Hime (Princess Mononoke) was coming along. On some days he would drive back again to Shinbashi for another meeting and then back again to Ghibli. Suzuki often held meetings out at Koganei or back in Tokyo that began at 10 pm and lasted for hours. He usually left the studio at 1 am or 2 am for his drive back home to Tokyo. He rarely slept more than four hours a night.

Suzuki is not a particularly large man, but he radiates a palpable energy, intelligence, and wit. Like Hayao Miyazaki, who is older than Suzuki by about a decade, Suzuki is instantly recognizable by anyone almost anywhere in Japan. His narrow face with John Lennon–style round glasses and a perpetual five-day beard and his extremely casual style of dress make him look like a person no one would ever mistake for a Japanese salaryman or believe was a director of a major company.

Despite living a good deal of his life in a car or in meeting rooms, Suzuki always had time to see every major Japanese and Hollywood film then playing. He had an unusually thorough and detailed knowledge of the roads, paths, and hidden alleyways of the Koganei-Mitaka area. None of these roads were ones Suzuki would have crossed in his back-and-forth travels between Ghibli and Shinbashi, and they often led to the most interesting hidden parks and special restaurants in the area. For someone so eternally busy, Suzuki managed to spend long periods of time alone and just thinking. He also spent long hours locked in windowless rooms attending to the excruciatingly time-consuming process of filmmaking. And somehow he still found time to mentor the people who worked for him.

The Tokuma Group of companies then consisted of Studio Ghibli (animation), Daiei Pictures (live-action films), Tokuma Publishing (the main company and a large publisher of a range of books from graphic novels to literature, nonfiction, magazines, and even poetry), Tokuma Japan Communications (music), Tokuma Intermedia (computer games and computer game magazines), Toko Tokuma (joint venture movie projects in China and independent films using Chinese directors), and Tokuma International (my company, engaged in sales of Tokuma’s entertainment products outside of Japan).

When I joined Tokuma International, all media companies in Japan were just beginning to experience the serious challenges to their traditional business models posed by computer-based entertainment products and a decline in the demand for things printed on paper, formerly known as books, magazines, and newspapers. Over at Ghibli, the studio’s primary creator, Hayao Miyazaki, was simultaneously working himself nearly to death on his new film, Princess Mononoke, and facing a monumental writer’s block in his struggle to come up with an ending for the film. Miyazaki would always work by writing the endings to his screenplays while the beginning and middle parts of it were already in production. When the production of the film would catch up to the unwritten parts of the screenplay, a general panic would set in. Ghibli produced approximately one film every two years, and to miss a release date could conceivably mean financial ruin for the studio.

With the business problems at Tokuma, the production problems at Ghibli, and the teething problems with the brand new Tokuma/Disney relationship in which Disney had contracted to distribute Ghibli’s films worldwide, Suzuki was driving back and forth between Shinbashi and Koganei quite a lot. He therefore spent a good part of his day in his car.

Toshio Suzuki was then and continues to be what is known as an early adopter. If a certain new technology is available, he will be one of the very first to start using it. Owing to his position in the entertainment business, major Japanese electronics manufacturers would often seek him out to try their prototypes of new devices. Spending so much time in his car, Suzuki was always looking for ways to turn his car into a mobile office, so that he would never lose working time driving from place to place.

Years before hands-free mobile phones became readily available in cars, Suzuki had one in his. Years before GPS systems became readily available in cars, Suzuki had one in his. He had an audio CD system in the trunk of his car that automatically rotated and played either a preselected menu of music or randomly selected music for him to listen to. The system was attached to four very fine speakers that replaced the ones that had come with the car. All of this gadgetry allowed Suzuki to conduct business during his hours on the road and to listen to his favorite music when he wasn’t on the phone.

Thanks to his hands-free phone system, Suzuki was among the very first humans capable of gesturing wildly and yelling at someone while driving (legally) as he commuted to work. Thanks to his mobile GPS and sophisticated music players, he could plot his escape from Tokyo’s famous traffic jams while steeped in the sounds of 1950s and 1960s pop music (“Big Girls Don’t Cry,” “She Loves You,” and “House of the Rising Sun”). Many of his gadgets were specially made for him and were designed to be installed in various places in his car, including on the dashboard on the passenger side.

I would often ride with Suzuki between Tokuma Shoten and Studio Ghibli. Once as we were cruising through relatively light Tokyo traffic, it occurred to me that his car was equipped with air bags.

“Suzuki-san, does this car have a passenger side air bag?” I asked.

“Yes, of course,” he said.

“So if we get into an accident, the air bag will deploy and the GPS thing and the phone thing and the CD player controller thing will all be driven into my body at warp speed and with lethal force, killing me instantly?”

“Well . . . yes, now that you mention it, I suppose it would.”

The systems in his car were down for a few weeks after that. No one would agree to ride shotgun until his technology friends had figured out how to place everything so as not to kill the front-seat passenger in the event of an accident.

No matter how busy Suzuki was, he always had time to do what was needed to make sure that my transition from a large American entertainment company (Disney) to Tokuma Shoten went as smoothly as possible. Most of his efforts in this respect involved keeping me isolated from contact with the company’s other divisions.

The mission statement for the new company and my job description was to sell the rights outside of Japan to anything owned or produced by any of the Tokuma companies and to handle any business of the Tokuma companies that involved dealings outside of Japan. This included managing the Disney relationship for the Ghibli films they would distribute, but it also included the Daiei films (Shall We Dance?) in markets where they had not been sold and the music, video games, and the Chinese-produced or -directed films.

One reason for setting up a separate company for the international business was to avoid the work rules of the rest of the Tokuma Group. Japanese companies then still worked a six-day week. Overtime, if required, was not compensated, even for hourly workers. Vacations and holidays, though earned, were rarely taken. And duties such as cleaning the office and serving tea or coffee were mandatory for all female employees (only). Suzuki understood that gaijin lacked the proper work ethic to submit to the normal working conditions in a Japanese company and would also resist applying the work rules to the new company’s Japanese staff as well. In order to function harmoniously in a Japanese company, the new company had to be separate and to have its own work rules.

Many years ago when I was still a student in Japan, I was out drinking with a Japanese friend in a backstreet section of Osaka’s Dotonbori entertainment district. It was late, maybe 2 am, and we were stumbling around looking for a taxi, having had a lot to drink in the bars and clubs called “snacks” that my friend often frequented. We came to a very narrow street, so narrow you could have stretched out a leg and reached the other side in a single step. The street had a pedestrian traffic light. The light was red. The streets were completely and totally deserted except for the two of us. Having lived for years in New York I instinctively moved to cross. My friend reached out his arm and prevented me.

“Red light,” he said.

“Oh come on,” I said. “It’s completely deserted. No cars are coming. No one else is around. Why would we let a dumb, inanimate machine tell us if it’s safe to cross?”

“Arupaato-san, of course I know it is safe to cross. But I have the inner strength to stand here and wait for the green signal. That is the problem with you gaijin. You are weak. You lack the discipline to stand here and wait for the green light.”

It was an argument that was hard to refute, from the Japanese perspective anyway. We gaijin don’t work on Saturdays. We might do overtime once in a while, but not as a regular thing, and we expect to get paid extra for it. We don’t share desks at work and expect to have a whole desk all to ourselves. We complain if the offices we work in are more crowded than the legal limits imposed by the municipal fire department. We don’t think smoking should be allowed in the office. We don’t think women with the same job description as men should automatically be required to make tea (coffee), wear uniforms when men doing the same job don’t, or neaten up everyone’s desk at the end of the day. We sometimes allow the people who work for us to tell us that we’re wrong and we even get angry when they fail to advise us that the truck they see roaring down the road, which we haven’t noticed, is about to flatten us. Not only don’t gaijin do the many basic things that every Japanese company worker understands, is expected to do, and expects others to do, but we’re not even aware of most of them.

Hence the solution of physically walling off the office that was Tokuma International from the rest of the Tokuma companies housed in the same building. Not only were the walls meant to protect the gaijin within from clashing with the normal Japanese people working nearby, but they were also meant to protect the Japanese workers from exposure to the gaijin next door and its gaijin-friendly Japanese staff. Tokuma International was the only no-smoking part of the company. No one worked on Saturday. The secretary didn’t wear a standard issue office lady (OL) uniform or clean desks (OK, she did make coffee). Each person had their own desk. And we had a reasonable amount of space to work in.

For those unfamiliar with the look and feel of a typical Japanese corporate business office, they typically look very much like the chaotic homicide squad rooms in American TV crime dramas, only more crowded and less well organized, and with no private offices for the lieutenants. The meeting rooms look exactly like the interrogation rooms where the suspects are grilled and bullied into confessing to crimes. Only the company’s president on the executive floor would have his own office. Even presidents of smaller subsidiary companies might share a desk with one or more assistants, though they would have larger desks than everyone else.

Even the offices of major Japanese corporations look as if Godzilla came rampaging through and management decided the cost of cleaning up or repair wasn’t justified. The employees are Japanese. They’ll make do. Each floor of a Japanese office building is generally designed to be used as a single, large open space. In even the most famous corporations, the staff share desks. Four or six employees to a desk, seated on both sides of it, facing each other with a computer or stacks of files serving as a semi-porous middle barrier. A single printer, copier, and fax machine is shared by an entire floor. Sometimes by two floors, and people might have to make a trip upstairs or down to pick up a printed or faxed document.

Tokuma Shoten’s offices sat in an impressively stylish architect-designed building. But the offices themselves were designed for Japanese employees. The Tokuma International office on the other hand, was designed for gaijin. Inside its newly erected walls, each of the four original Tokuma International employees had his/her own reasonably sized desk and computer. We had a printer, copier and fax machine for four people. We had a sofa and two armchairs for casual meetings and a table and four desk chairs for meetings where papers and documents had to be spread out. We had bookcases full of relevant but seldom-used legal and industry tomes plus massive Japanese-English and English-Japanese dictionaries. We had a display cabinet containing one of every consumer product or book Studio Ghibli had ever produced.

Our tenth-floor office also had large corner windows with views that extended all the way out to Tokyo Bay. From my desk I could see all of Japan’s various modes of transportation at a single glance. There was the shinkansen Bullet Train just slowing on its final glide toward Tokyo Station. The various color-coded JR local and long-distance lines came and went every few minutes. The newly built and driverless Yurikamome train zipped along on rubber wheels toward the Odaiba entertainment area and the Big Site convention center. The aging but still graceful Monorail, a leftover from the 1964 Olympics, leaned precariously leftward as it rounded a curve on its way to Haneda Airport.

There were the gracefully arching branches of the Shuto, the overhead highways. These were clogged with traffic that barely moved all day. Once or twice a day I could spot a ferry just easing into its berth at the Takeshiba piers after completing its twenty-four-hour trip from one of the far-away Izu-Ogasawara Islands, incongruously an official part of metropolitan Tokyo. There was the newly built Rainbow Bridge standing astride the harbor and linking it to the island of Odaiba. The bridge was silvery white in the morning sunshine or bathed in colored lights against a hazy pink and purple sky at dusk.

All day, passenger jet aircraft banked low over Tokyo Bay on their final approach to Haneda Airport. Immediately below, bustling Shinbashi’s wide main streets were packed with cars and busses mired in the heavy traffic. The warren of narrow pedestrian-only alleys in the mizu shobai (bar) district were mostly empty in the morning and crammed with wandering pedestrians once the evening rush began. At the beginning and end of the lunch hour, which everyone took at exactly the same time, the sidewalks were full of people.

Just behind our building, ground had been broken for the soon-to-be new modern high-rise district of Shiodome. But the initial digging had unearthed a forgotten mansion, a daimyo yashiki, and now all construction was on hiatus while anthropologists used toothbrushes to excavate Edo-era teacups and teapots from the muddy soil. The original Shinbashi train station, Japan’s very first, had also been discovered nearby and was similarly being excavated and restored.

It was a spectacular view out my office window. And I have to admit, I spent time enjoying it. Only Mr. Tokuma’s own office two floors up had so special and so expansive a view of Tokyo. His was, of course, much bigger and much better.

To populate our special office, Suzuki, always conscious of the interpersonal dynamics of the workplace, had hand-picked Tokuma International’s initial operating staff. To begin with, there was one male from the Tokuma publishing side of the business with experience in computer games and accounting. And there was one female from Daiei Pictures with experience in overseas film sales and a good knowledge of Tokuma politics.

To avoid the potential for sexual complications at work, Suzuki made sure that the male staff member was younger and majime (boring), and that the female staff member was the senpai (senior) in terms of industry knowledge and experience. This, he believed, combined with his having specifically chosen two people who he was sure would not find each other attractive, would preclude any workplace complications from an office romance. As it turned out, these two original employees ended up marrying each other about a year later and left the company.

Since nearly all of Tokuma International’s business was with people from outside of Japan, a secretary who could speak English was needed, or at least one who could receive phone calls convincingly in English. None was available from inside the Tokuma Group (a sign of a truly Japanese company), so we proceeded to hire one from the outside. This gave me the opportunity for firsthand experience of how Japanese companies hire their employees, a process that differs somewhat from how Western companies do it.

Suzuki let me know that he had contacted an employment agency and had scheduled appointments with three prospective candidates. The first candidate, a young woman in her early twenties, was shown into a conference room accompanied by a representative from the agency, and we were joined by three managers from Tokuma Shoten. To my surprise, there would be a single interview at which all parties would be present. In America we tend to do it one-on-one.

The questions asked also differed from what would typically be asked in an employment interview in the US. What were the young woman’s religious beliefs? Did she have a boyfriend? If not, why not? If she had a boyfriend before but not now, was it she who left him or did he dump her? How much money did she have in her bank account? Was she planning on having children any time soon? Generally these types of questions are considered bad form in an American employment interview or are possibly actually illegal.

The hardest part of the interview for the first candidate came when she was suddenly told to start talking in English to the gaijin. The girl looked around the table at five unsmiling faces and at one face trying hard to look friendly. She hesitated briefly, and then she burst into tears. The situation did seem unfair to her, though when hiring a secretary for a company that mainly does business with non-Japanese people, you probably do not want to hire someone who breaks down and cries when asked to speak English with a foreigner.

This first candidate was not hired. I asked Suzuki if we could do the subsequent interviews with fewer people present. I thought that if we were going to make the candidates talk about their sex lives, their religion, and how much money they had in the bank, it might be better with a smaller group. Suzuki seemed puzzled by the request but agreed.

The next candidate arrived with a representative from her agency and her mother. This time the Tokuma side was represented by Suzuki and myself and one other person. The questions were as before (the mother looked uncomfortable), but the English part of the interview was between only the girl and myself. We ended up hiring her. However, as it turned out she did have an unfortunate tendency to burst into tears from time to time, and eventually we had to replace her. She ended up marrying someone in the office next door.

Our beginning staff of four people spent the first few weeks in the office just setting things up. I immediately discovered that there are two major things about working in a Japanese company that set it apart from working in an American company: frequent and pointless internal meetings and aisatsu.

We don’t really have aisatsu in the USA. It can be roughly translated, depending on the context, as greetings. In this case, in-person greetings. For about the first week in the new company, every single Japanese person I had ever known, or had even ever met, stopped by unannounced to congratulate me on my new position and to sit and chat for five to ten minutes about nothing in particular. People I had never met dropped by unannounced to congratulate me on joining my new company. The office was filled with pots of lovely white orchids: gifts from people who had wanted to drop by but couldn’t make it. Some were even from the heads of major Japanese corporations. Although I was impressed, I could never understand how, with this many people always just dropping by and having nothing in particular to talk about, anyone could ever get any work done. At least for the first few weeks of a new company’s existence.

Once the external ceremonial aisatsu had begun to die down, I was visited by various people from within the Tokuma companies. The first was Mori-san from Toko Tokuma, the company that worked with partners in China to produce Chinese films by Chinese directors. Mori-san was a serious-looking man with a large scar running down the side of his face, gleaming yellow eyes, and tobacco-stained brownish teeth. He was rumored to have worked for the Japanese CIA in Taiwan during the War. Mori-san sat with me in my office and mustered what for him passed as a pleasant voice and told me he had just dropped by to warn me to stay out of his China business.

The head of Daiei Pictures, the live-action movie production group, dropped by with a few of his senior managers to let me know that yes, they had been told that I was in charge of selling their films abroad, but no, Daiei didn’t need any help from me. They had their own people who had managed perfectly well before my arrival and they would continue to do so without me.

The head of the Tokuma legal department dropped by to let me know that he was in charge of all contracts and that I was not to even think about negotiating a contract without consulting him first. The head of book publishing came by to say that he’d heard I would be helping him with book deals outside of Japan, but that since I didn’t have any publishing experience, I should just leave all that to him. And the head of the interactive games business came by to thank me for not bothering to use my Disney contacts to try to expand his distribution business outside of Japan. The head of the music division delivered this same message by not even bothering to come over to see me.

Unlike the aisatsu visits from people outside the company, the aisatsu visits from the people within the company at least seemed to serve some kind of obvious purpose. The same could not be said for the frequent internal meetings I was required to attend. I understood that the real discussion of any issue in a Japanese enterprise takes place before any meeting is called. If there is an issue that needs to be resolved or a plan someone is seeking to have approved, the relevant parties meet informally, usually one-on-one or in very small groups, and often at a bar or restaurant somewhere. In a less formal setting, fueled by alcohol or not, company employees float ideas and get a sense of who might be in favor or who might oppose a thing, and crucially, what the real reasons for being for or against might be. The process of visiting and obtaining the approval of all required persons in advance is called nemawashi (securing the roots). In this way the arguments for or against any proposal or new idea and the decision makers’ positions on the proposal have all been fixed long before any formal meeting takes place.

Once the nemawashi has occurred, a meeting is called to pretend to discuss the matter in question, and the attendees vote on the outcome in accordance with the positions they have previously (and privately) confirmed they would take. By the time the meeting has been called, everyone attending already knows what’s been decided. In the meetings I attended, I always hoped that there would be at least one guy who never got the memo or who was out of town or something, and would come to the meeting, be astonished at what was being proposed, and argue about the decision. Of course that never happened. It always surprised me how much time and energy went into the fake and pointless discussion of something that had already been decided, and that I was always the only one in the room who seemed to mind.

When setting up our new company, Tokuma International, we had hours and hours of “discussion” meetings to determine the new company’s official policies and work rules. Japanese law requires any incorporated company to have official policies on a number of things, including rules governing employment, though surprisingly no one seems to pay much attention to them once they’re finalized and written down. Suzuki and I had worked them out in advance, and Suzuki had done the nemawashi with some of the other division heads and explained the rules to Mr. Tokuma and gotten his approval.

Nonetheless, a series of meetings were held to discuss the policies and rules. The meetings were attended by no fewer than a dozen people, including Mr. Tokuma himself. We slogged through the minutiae of potential human resources issues and rules and regulations. We once spent the better part of an hour deciding whether an employee making his/her first business trip should be allowed to purchase a suitcase at the company’s expense, which was the rule in the other Tokuma Group companies, and if so, exactly what kind of suitcase it could be and how much such a suitcase would cost.

We also briefly touched on larger issues like maternity leave, long-term sickness leave, grounds for dismissal, employee evaluations, and performance review frequency, though none of these topics held the attention of the participants the way the suitcase issue had. All of this seemed like overkill for a company that had only three employees and was never expected to have as many as a dozen—especially since the rules that Suzuki and I had decided on and Mr. Tokuma had approved were already being printed up for submission to the government agency that monitors such things. And it wasn’t as if the other people in the meetings didn’t know this.

Another feature of Japanese meetings that has always puzzled me is that once a person begins to talk, no matter what he/she has to say, the floor is his/hers for as long as he/she thinks he/she needs to say it. Even when the person is saying something completely and wildly off topic, overlong, or embarrassingly inaccurate, no one ever intercedes, politely or otherwise, to end or limit the speech. The person just keeps going on until he/she is done.

Japanese people are used to happyo, a term that roughly translates as “presentation.” Long speeches mark many of Japan’s social occasions. Weddings and farewell parties require an endless series of long speeches. From an early age Japanese people are often pointed to at random, in school say, or at social gatherings, and asked to stand up and talk. And they almost always do, whether or not they actually have anything to say. At a Japanese business meeting, every single person in the room must talk, whether or not they have anything to say. There is never a sense of trying to come to a conclusion or challenging or discussing the opinions being talked about. Just a series of each person in the room articulating a position that may or may not have direct or even indirect relevance to whatever is being discussed.

On the other hand, even a meeting where everything is decided or has been decided behind the scenes can serve other functions. Where people sit matters. Who sits closest to the president matters. Who is asked to speak in what order reveals things about the company’s power structure, which does shift from time to time. Who is invited to the meeting in the first place matters. The meetings may not bring forward the actual business of the company through critical discussion and evaluation of options. But they do let the people in it know a good deal about what is actually going on inside the company. The important information that you took away from a meeting often had very little to do with the topic that was being discussed.

Tokuma-shacho

The chairman of the Tokuma Group was Yasuyoshi Tokuma, also variously known as Tokuma Kokai or Tokuma-shacho. Whatever stereotypical images there are of Japanese businessmen, Tokuma-shacho conformed to none of them. A consensus building, risk-averse team player, indistinguishable from his peers in a blue suit he was not. He was a quirky, self-confident, opinionated, strong-willed, blustering individual capable of swimming gleefully against the tide of public opinion and conventional wisdom. He consciously sought to appear bigger than life. He was exuberant and joyful but also capable of rage and thunder. He was a tall, good-looking man who projected an aura of authority. He was your grandfather on steroids (if your grandfather was Japanese). He spewed out transparent untruths so convincingly and entertainingly that no one believed them for a moment yet acted as if they did. He was capable of infinitely subtle Machiavellian intrigue that succeeded because it came wrapped in motives that seemed so comically obvious he was often underestimated. What you thought was really going on was often just diversion.

It took me quite a while to realize that Tokuma-shacho’s self-aggrandizing, obviously exaggerated fabrications were meant to be dismissed as folly, because while you were congratulating yourself on seeing through the pretense, you were missing the real story. Tokuma-shacho could transform himself from a blustering, self-absorbed egoist into a wise elder statesman sharing his wisdom with you, secretly and off the record, in the space of a few sentences. His advice, when he gave it, could seem profound and usually made good practical sense. His mottos, which he repeated frequently, were “never let anyone else write the screenplay of your life” and “never let a lack of money stop you, because the banks have plenty of it just for the asking.” Knowing how to borrow large sums of money was his greatest talent.

When I joined Tokuma Shoten, Tokuma-shacho was in his seventies. He was strongly built and handsome in the manner of an aging or retired movie star. He had a deep, gravelly voice that he broadcast stirringly to an audience of hundreds without a microphone. In private, the voice could drop to a sandpapery stage whisper, if he wasn’t yelling at you for something. He had the demeanor of an old-time politician or yakuza don. It was difficult to imagine him sitting down to give advice to famous Japanese politicians, or to heads of major modern corporations like SONY or Nintendo or to Japan’s first-tier major banks, as he often claimed. Yet there were newspaper articles, complete with photos, to prove that at least some of his stories were actually true. You were always sure that he was making up most or at least some of what he said, embellishing the details and adding here and there to make a good story, but there was always just enough verifiable truth in it to make you stop and wonder. No one ever believed his stories, and yet no one completely disbelieved them either.

Mr. Tokuma was a fixer. He was a man who could get things done behind the scenes. If Politician A needed to speak to Politician B or Captain of Industry C, but couldn’t be seen in public doing so, he could speak to Mr. Tokuma and Mr. Tokuma would pass along the message. He was famously a friend of the Prime Minister Uno Sosuke. In 1989 when the Mainichi Shinbun broke with tradition and reported that then Prime Minister Uno had been keeping a geisha, Uno rode out the media firestorm hidden away in Mr. Tokuma’s twelfth-floor office suite for the better part of a week. Uno was later forced to resign after only three months in office. It was unclear whether the cause had been the public outrage over the moral issue of a prime minister having a kept woman, or the Uno regime’s being blamed for the prior administration’s imposition of an unpopular nationwide consumption tax, or that Uno had kept the geisha on such a pitiful allowance she had sought out a newspaper reporter to complain about it. In any event, it had been Mr. Tokuma who kept Uno out of sight while his political party tried to contain the damage.

Once when returning from lunch and entering one of the two elevators in the lobby of the Tokuma Shoten Building, I noticed that people were avoiding the elevator I had just entered. People in public in Japan sometimes avoid sitting next to gaijin on trains or standing next to them in elevators (we are unpredictable, apparently), but this rarely happened in the Tokuma office building. Then I noticed that the other person in the elevator with me was clearly a yakuza. He was as wide as he was tall, muscular, wearing a dark suit with a narrow tie, had on sunglasses, and had facial scars, a crew cut, and an unambiguous attitude. He was carrying a large paper shopping bag in each hand. I casually glanced down to see what was in them. Though they were covered on top with loosely positioned Hello Kitty hand towels, I could clearly see that underneath the towels the bags were full of cash: bundles of ¥10,000 notes bound with rubber bands. No one else got on the elevator and the doors closed. I pushed the button for 10 and my companion asked me to push 12, the executive floor containing only Mr. Tokuma’s office and his private meeting rooms.

The twelfth floor of the Tokuma Shoten Building was a kind of world unto itself. It contained the Tokuma boardroom, a very beautifully appointed president’s office with an adjoining smaller conference room, and a few secret rooms in the back, including a storeroom full of gifts that the shacho had received or that the shacho would eventually give to others. There was expensive-looking original art everywhere. The gatekeeper to the president’s office was Tokuma-shacho’s personal secretary, a very elegant woman named Oshiro-san.

If you were summoned into the shacho’s presence you would get a call from Oshiro-san. If you needed to see Tokuma-shacho for some reason, you phoned Oshiro-san and she would either fit you in as appropriate or politely inform you that your request had been rejected. If you were a visitor from the outside or if you came up to the twelfth floor in the company of a visitor from the outside, at the end of the audience you would receive either a package of something called dokudamicha, a kind of supposedly healthful green tea, or a small present and a package of dokudamicha. Somewhere on the twelfth floor there was a storeroom containing a mountain of packages of dokudamicha.

Any summons to the twelfth floor was guaranteed to be interesting. If there was something Tokuma-shacho wanted you to do for him, Oshiro-san would call you up. It was never come up at 3 pm or be here on Tuesday at noon. Advance notice was rare. When Oshiro-san called, the shacho wanted you right away. You dropped whatever it was you were doing and you went.

Being ushered into Tokuma-shacho’s office always felt special. He had an enormous, beautiful mahogany desk that seemed to be overflowing with presents or framed documents he had just received and unwrapped. Two of the walls were all glass with sweeping views all the way out into Tokyo Harbor. It was a philosopher’s view of the city, similar to my own view from my office, but much grander. From up here the Bullet Trains rushing to and from Tokyo Station, the ferries docking or departing for Tokyo’s outer islands, and the planes banking low for their descent into Haneda Airport seemed somehow more significant. As if the person with this view of Tokyo had the kind of real power to change what you were seeing down below.

If you stood by the window in Mr. Tokuma’s office, you could see down into the Hama Rikyu Imperial Gardens where the emperor of Japan had once hunted ducks by day and held moon-viewing parties at night. With no taller buildings nearby, you had a sense that you were up on top of the world. Even the emperor of Japan and the real estate that he owned was down below you.

Whether first-time visitor or company employee, once you got the required dose of the art on the walls and the view out the windows, you were ushered to a suite of sofas and chairs arranged around a large glass-topped coffee table. This is where you were invited to sit and wait for the shacho to join you while observing him in action. He was usually on the phone when you came in. The single armchair looking outward was reserved for Tokuma-shacho, and on the table in front of it was his personal teacup, a very beautiful and very rare Edo-era blue and white Imari porcelain with a mountain and waterfall landscape baked into it. The two chairs facing the desk were usually reserved for in-house visitors. The sofa with its back to the desk was usually stacked high with books or more items that Tokuma-shacho had received as gifts but was cleared off to be used by outside visitors.

No meeting with the shacho ever began until Oshiro-san had brought in a tray with freshly brewed coffee and fancy French cookies or little cakes, followed by Japanese tea. Once the shacho settled into his chair, which was bigger than the others, he never seemed to be in a hurry. He asked how you were doing, what you were up to. There was personal conversation while you ate the cookies and sipped tea and/or coffee. And eventually he would get around to whatever it was that he wanted you to do for him. One such theme, for example, was his wanting to meet personally with Disney’s then chairman Michael Eisner. How could this be arranged and when? Several times he asked me up to his office for advice on how he could arrange to meet with Bill Clinton (Harvey Weinstein had suggested that he could arrange it).

Sometimes the meeting with Mr. Tokuma would be about an offer he had received from someone not Japanese, and he wanted a response drafted in English. Michael Ovitz once invited him to meet Christie Hefner to see if Tokuma Shoten would be interested in publishing Playboy in Japan (he wasn’t). Steven Segal wanted him to invest in one of his films (he didn’t). Every three or four months he received an invitation to executive produce a film somewhere in Europe that included a financial summary, and he asked me to look it over.

Sometimes Mr. Tokuma would ask me and Moriyoshi-san, who worked with me, to come up to his office, and there would be no point to the meeting or request at all. Oshiro-san would come in with individual cups of Häagen-Dazs (always vanilla) or little plastic containers of crème brulée. We would eat. There would be no talking at all sometimes; just eating. We would finish eating, he would thank us, and we would leave. That would be it. Moriyoshi-san and I would leave, look at each other but not voice the question “what was that about?” at least until we got back downstairs.

The actual business of Tokuma Shoten was entertainment and publishing. Mr. Tokuma had started his company by recognizing talent and promoting it. Writers and other artists loved to be represented by Tokuma because he firmly believed that the creative part was up to them, and he seldom interfered in any way with what they did. Once he selected someone he had decided to work with, he left the creative side of things entirely in their hands. It helped that he was always less interested in their actual work than he was in what use he could make of the relationship. He published books. He hired writers and other staff and let them create magazines. His companies funded the films of Akira Kurosawa when no one else would. He invested in Chinese filmmakers whose government threatened to ban their films. And he started Studio Ghibli by finding the money to finance the then relatively unknown Japanese directors Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki.

Studio Ghibli was founded in order to keep the team that had produced Kaze no Tani no Nausicaä (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind) together so they could go on to make more films. A great deal of mythology surrounds the creation of Studio Ghibli. Toshio Suzuki has said that the name for the studio was chosen because Ghibli is a term WWI Italian fighter pilots used for the hot wind that blows out of the Sahara Desert. Suzuki maintained that Ghibli’s purpose was to blow a hot new wind into the world of Japanese film animation. Hayao Miyazaki, when asked why the name Ghibli, said the name was chosen when Suzuki told him they were getting their own studio and it needed a name. Miyazaki says he was looking at a book of WWI aircraft when Suzuki came in, and randomly pointed to a plane on the page he had open at the time. Both or neither may be true. Either way, it was Yasuyoshi Tokuma who came up with the money to make it happen.

Public Speaking

To manage his companies, or perhaps more accurately, to hear the reports on what was happening in his companies and create a narrative to describe it to the outside world, Tokuma-shacho held three monthly meetings on a regular schedule. There was a department heads meeting, a board of directors meeting, and an all–Tokuma Group employees meeting. The latter was a monthly address to the assembled employees of the companies that made up the Tokuma Group. There was also a semiannual stockholders meeting. Each meeting began with a speech by Tokuma-shacho. The speech took a slightly different form depending on Mr. Tokuma’s mood and what was going on at the time. It was somewhere between a comedian’s stand-up monologue and a politician’s formal address.

Each of the meetings had its own purpose and its own audience even though there was a good deal of overlap in the contents. At the department heads meeting attended by thirty or so department heads or subheads seated around the huge board room table on the top floor of the Tokuma Shoten Building, each department head was required to stand and relate the highlights of his/her department’s activities that month and say what kind of things were expected to happen in the coming months. All seats were assigned. You had to be on time. The meeting started at 10 am and if you were not in your seat by 9:55 am you were late.

The current status of each person in the company was revealed by his/her proximity to Tokuma-shacho seated at the head of the table. Toshio Suzuki was always seated to his right. No one managed to hold the seat to his left for more than a meeting or two. Because Mr. Tokuma loved intrigue, most of the other positions at the table often changed, and rivals of equal status sat equidistant from the boss, facing each other at the table. I always sat next to Suzuki, partly because the idea of having a gaijin at the table in the first place was meant as a kind of status for the company and partly because the gaijin needed frequent whispered commentary to understand what was going on.

Tokuma-shacho always opened the meeting and for the first half hour regaled the assembled group with a reading of selections from his current month’s diary. The diary, the parts of it he read anyway, contained secrets and glimpses behind the scenes of Japan’s centers of commercial and political power. He used the diary as a kind of jumping-off point for his monologues. He would tell stories about famous people. Sometimes he would interrupt himself with his thoughts on politics and society or just to tell a joke. He was one of the most riveting public speakers I have ever heard. And he expected no less of each person in the room when it was his/her turn to speak.

When you spoke at one of these meetings, you had to speak up in a loud, confident, and manly voice (even if you were a woman). Often not much happened in a particular department from month to month. Listening to a speaker trying to embellish his/her business activities and make it sound as though progress were being made could be either painful or sleep-inducing (sleeping in a Japanese business meeting is OK if done correctly; the proper position is arms folded across chest, chin resting on top of chest, and facial expression ambiguous enough to be interpreted as listening with eyes closed). Often the topic being reported was some business-related failure that everyone in the room understood Tokuma-shacho himself had caused but would not admit to. The publishing division’s numbers were down because a highly touted new book by Sidney Sheldon had failed to do any business. Tokuma-shacho had taken pride in negotiating the outrageously generous contract with the author by himself, against the advice of his head of publishing. Because no one could actually blame Mr. Tokuma aloud at a meeting, the head of publishing had to take responsibility for vastly overpaying Sidney Sheldon.

No remedies or actionable plans were ever offered at the meetings, and there were rarely comments or questions. The department head or subdepartment head said his/her piece, heads nodded, and the next person was called on. There were to be no surprises and no introduction of brand-new information. But at first I didn’t know that.

At the very first department heads meeting I attended, all I had to do was to stand up and introduce myself. That went fairly well. At the second meeting, though, I got a little carried away and got into trouble. Some of the international business had been handled by Tokuma Shoten executives. There was a group of them who took on whatever project came up that didn’t fit into another category or that no one else wanted to deal with. The people in charge of the various foreign projects were more than happy to turn them over to me. One of the more senior generalists, a man named Ohtsuka-san, had been assigned to be my in-house Tokuma liaison (probably because Tokuma-shacho didn’t trust Suzuki-san to be my only mentor). Ohtsuka-san had been in charge of Korea. There was a Korean company that Tokuma did various kinds of business with, and Ohtsuka-san wanted me to meet its chairman and take over the business relationship.

Ohtsuka-san had arranged for the first face-to-face meeting with the chairman of the Korean company to take place over dinner. The dinner was scheduled at 4 in the afternoon in a fairly expensive sushi restaurant in nearby Higashi Ginza. I thought it was odd that a dinner would be scheduled so early and wondered if the sushi restaurant would even be open then. I went to the appointed place at the appointed time and was introduced to the head of the Korean company, Chairman Wook of Daigen Communications (we always referred to him as the Kaicho). After ordering beer, Ohtsuka-san downed his as soon as it arrived and then, to my astonishment, stood up, gave a curt bow, and just left.

For the next three and a half hours over sushi and beer, Wook-kaicho explained to me everything I didn’t know about the film business in Korea. Most of what I didn’t know had to do with the historical relationship between Korea and Japan. It was illegal to screen Japanese films in Korea, partly because of the lingering animosity felt by many Koreans toward Japan after WWII, but also due to economic protectionism. Korea wanted its own film industry to flourish, and Japanese films, popular with Korean young people, were a threat.

The ban on Japanese films was gradually being loosened, but only for Japanese live-action films. The ban on animated films was less likely to be lifted, because of the many indigenous fledgling Korean animation studios and the fact that animated films were watched by children. After a good deal of expensive lobbying by companies like Daigen that wanted to import Japanese animation, the only exception the Korean lawmakers would concede was for films that had won major international awards. Theatrical distribution would be allowed for those films but not TV broadcast or video sales.

Wook-kaicho explained that there were Korean businessmen and a few Korean politicians who were actively campaigning to reverse this unnecessary remnant from another era, and that things were changing and certainly would change in the near future. Soon, he said, all Japanese live-action films would be allowed in and the ban on airing them on TV would be lifted. The ban on animated films and TV shows would remain in place for a while, but it was only a matter of time before that too would be lifted.

I asked the Kaicho how he knew the Korean government would lift the ban. He leaned in closely and spoke in a low voice. “We know the people who make these decisions,” he said. “We have ways to influence them.”

“You mean bribes?” I asked.

He leaned back, picked up his glass, and had another sip of beer.

“I know for a fact that the ban will be lifted by the end of this year,” he said.

“What is it you want me to do?” I asked.

The Kaicho’s problem was that he had been a very early supporter of Ghibli films. He had entered into a ten-year license contract to distribute the films in Korea. The end of his contract was fast approaching. The contract stipulated that if the ban on Japanese animated films was still in place when the contract expired, Daigen would lose the large minimum guarantee it had paid up front to Tokuma for the Korean rights to the films. Ten years had nearly passed. The ban had not been lifted. The Kaicho wanted me to extend the license for another ten years for free. “I know politicians. I’m spending money. I promise you the ban will be lifted by the end of the year. I guarantee it,” he said.

At the next department heads meeting when it was my turn to speak I announced that the longstanding Korean ban on animated films was about to be lifted. My statement was met with a tsunami of uproarious laughter. Waves and waves of it washed over me. Tokuma-shacho turned to me and in an almost kindly, grandfatherly voice said, “Ah, you’ve been talking to Wook-kaicho. You see Arubahto-san (Mr. Tokuma could never pronounce my name correctly), Wook-kaicho has been coming to Tokyo twice a year for the last ten years telling us exactly the same thing. We believed him at first too. The ban won’t be lifted any time soon, no matter what he tells you.”

And of course, it was not.

In addition to standing up to speak at the department heads meeting, every month each department head was required to make a short speech in front of a large group representing the roughly thirteen hundred employees of the Tokuma Group. The meeting took place in the Tokuma Shoten Building’s in-house theater, Tokuma Hall. Each department head in turn mounted the big stage and addressed the three hundred assembled employees. The prospect of speaking in Japanese on stage in front of a large auditorium full of people terrified me, and it happened once a month.

I knew I would always be the third speaker. After Tokuma-shacho himself and just after Suzuki-san. Tokuma-shacho was a consummate performer. His speech would always be in equal measure topical, thought-provoking, humorous, and altogether relevant. It was delivered in the booming, stentorian tones of an accomplished stage actor, but also dropped to a coarse and earthy intimacy as required. He could be grandfatherly and wise or thundering and angry, or very, very funny. Of course, almost everything he said was completely made up and most of it untrue, and his audience stayed riveted to his every word. He was a really good public speaker.

Then Mr. Tokuma’s protégé Toshio Suzuki would stand up and speak. Usually Suzuki was even better than Tokuma-shacho. Suzuki’s speeches had the same qualities, and what he lacked in gravelly tone and the mellowness of age he made up for in the sharpness of his wit and the fact that his content wasn’t made up. What he said was clear, concise, and unobvious. He often said out loud what others were only thinking. He had a good strong speaking voice. He was also a really good public speaker.

These are the two guys I followed when it was my turn to speak.

The only way I could deliver a speech in Japanese was to practice it beforehand. I would write out what I wanted to say and then I would translate it into Japanese. Then I would show my Japanese translation to someone and make sure there were no obvious translation errors. And then, on the day I had to deliver this speech, I would spend the entire morning and early afternoon in the bayside park inside Hama Rikyu that was a five-minute walk from the Tokuma Shoten Building. I chose a secluded part of the park and spent hours there memorizing my speech and practicing its delivery out loud. I suppose if it had ever rained on the day of the speech I would have had to cancel it and go into hiding.

With nothing in my head but my speech, I would return to Tokuma Hall and take my front row seat next to the Tokuma Japan Communications starlet of the month. Tokuma Japan Communications was the music division of the Tokuma Group. They represented many talented and even occasionally very successful musicians, and also some who sold CDs based on how good they looked on the CD’s cover. New, young, female artists were introduced to the company at the monthly meetings.

For some reason, usually sitting next to me as I awaited my turn to take the stage was the newest of Tokuma Japan Communication’s starlets. Typically she was a girl of about sixteen with an adult woman’s body that was more or less contained in an attention-getting mini-skirt and abbreviated top. Before the speeches began, her name was announced and she stood up, teetered on her vertiginous platform heels, and turned to nod, jiggle, and wave to the audience. Upon seeing her move at close range, parts of my speech would suddenly disappear from my memory. For some reason, these young women always made me think of evolution, biology, and natural selection. Even a gigantic dinosaur could function with a brain the size of a peanut.

Tokuma’s and Suzuki’s speeches having wowed the audience, my name would be announced. I cast one final glance at the lovely starlet, now back in her seat again crossing her legs to get comfortable. Then I strode confidently forward to take the stage. Speaking in a foreign language, no matter how skilled you might be, can be like trying to eat or drink immediately after a visit to the dentist. You’ve had your gums injected with Novocain and you may or may not be going through the food and drink intake motions properly, but you just don’t feel a thing. You think you’re doing it right, but you can’t really tell. If you’ve just said something completely and devastatingly wrong, you will only know it when your audience reacts. US President Bill Clinton had a translator on a state trip to Poland who translated a presidential greeting for the Polish press saying that the president had a deeply felt need to have sexual relations with Poland. Probably it was a grammatically correct translation. Only the colloquial usage was off.

Although I was emphatically not a good enough speaker to follow Tokuma or Suzuki, I was very lucky in what I had to say when I got up on the stage. We were in the midst of the seemingly endless process of making the English-dubbed version of Hayao Miyazaki’s record-breaking film Princess Mononoke with Miramax, then a subsidiary of the Walt Disney Company. Every week Harvey Weinstein, the chairman of Miramax, was claiming that he was about to hire someone new and amazing for the film’s English-language cast. All I had to do was report it. The other department heads were doing updates from their increasingly struggling businesses. There wasn’t much good news to report, and Mr. Tokuma didn’t like to hear bad news at the big meeting, so mentioning crowd-pleasing topics like business disasters and potential financial collapse was out. While everyone else was struggling with their topics, I was delivering Entertainment Tonight, name-dropping the names of America’s most famous movie stars courtesy of Harvey Weinstein’s expansive vision of the possible (but the very unlikely).

Up I would go onto the big stage with hundreds of pairs of eyes trained on me, the audience’s ears alert from having been enlightened and entertained by the dynamic duo of Mr. Tokuma and his old-world (samurai era) blustering brilliance and Mr. Suzuki and his hip, insightful, and funny message that the company was about to harness new technologies and ride them to success. I took the microphone and tried my best to sound good in Japanese. I did my best to deliver my speech in manly, confident Japanese.

It is a fairly well-kept secret in Japan—something that the Japanese will not tell you until you’ve been there for twenty-five years (if then)—that most foreign males speak like women. The vast majority of Japanese-language teachers are women, and they never really dwell on the fact that men and women speak the Japanese language very differently, and that for a man to speak like a woman immediately reduces his effectiveness as a public speaker to near zero.

The Japanese in general are still fairly open about how they consider blacks and gay people to be inferior (though less open about how they think the same of Chinese and Koreans and a group of Japanese former outcasts known euphemistically as burakumin, “village people”). As a man, when you speak like a woman, the first impression you give is that you are effeminate or gay or both (or Chinese, depending on how you look). When I first learned this, it was pretty much already too late to correct. I also felt even more self-conscious about public speaking than before. And thanks to our chairman, Tokuma Shoten had a particularly manly-man culture of behavior. But then, how hard is it after all to stand up on a stage and reel off the names of America’s most paparazzi-plagued movie stars?

I would begin my talk by doing a little business updating, giving some information about the overseas sales of the company’s animated and live-action films. Miramax had also bought Daiei’s hit film Shall We Dance? and had big plans for the US release. After putting up some numbers, which always sounded more impressive expressed in dollars or euros because most people couldn’t do the math in their heads, I would launch into the report on the casting of the US version of Princess Mononoke. The cast list changed weekly and Harvey Weinstein rarely distinguished between wished for and confirmed. Leonardo DiCaprio agreed to play Ashitaka. Robin Williams is going to perform Jigo Bo. Juliet Binoche will be Lady Eboshi. Cameron Diaz will be San. Meryl Streep is going to do Moro. The audience was impressed and didn’t even seem to notice or mind that actors who had committed one month before would then be out in the next. I was on the verge of discovering one of Tokuma-shacho’s own secrets: for some audiences, if you’re entertaining enough, it doesn’t really matter that what you are saying isn’t factually accurate or strictly true. A whiff of truthiness will suffice.

Also, if you are a gaijin giving a speech in Japanese you start out with a huge advantage. You get a lot of points just for the fact that you can speak and are speaking a more or less recognizable version of the Japanese language. Yes, if you are a gaijin and male you are probably using mostly the female forms of speech that you learned from your female Japanese teacher. Many of the words you choose are wrong, like in the film Sophie’s Choice when Meryl Streep’s character misidentifies a seersucker suit as a cocksucker suit or like President Clinton’s Polish translator getting the wrong word for “delighted.”

As a gaijin you’re lovable and amusing and maybe less threatening by being imperfect. The audience forgives you for your cultural and linguistic mistakes because at least you’re trying. Like a little kid, you’re not expected to understand the complexities that make up the Japanese psyche or the subtleties of the language that give it a voice. Whatever you do know about it just makes you seem precocious. So, as a public speaker you succeed even when you’re not really good at it.

It may not be fair, but fair after all, is not really an Asian concept.