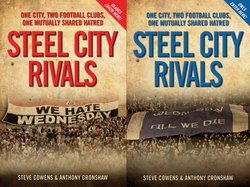

Читать книгу Steel City Rivals - One City. Two Football Clubs, One Mutually Shared Hatred - Steve Cowens - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWEDNESDAY RULE OK

Not many people will argue that Wednesday had the lion’s share of battle victories during the 70s. Their mob, the EBRA (East Bank Republican Army), had big numbers, and in those ranks stood some big hitters. The SRA (Shoreham Republican Army, later to become the Shoreham Barmy Army) themselves had some good lads but nowhere near the quality and numbers that Wednesday could produce. Many a time, especially in the then named County Cup games (a Cup competition between Rotherham, Doncaster, Chesterfield, United and Wednesday), both teams would infiltrate each other’s Kop, with Wednesday amassing big numbers on United’s Shoreham End.

The United lads gallantly tried to defend our turf from the invading snorters but they would often finish off second best. I was far too young in those days to get involved in the combat but I do remember looking up at our Kop from the John Street terrace during games with Wednesday; they had more on our Kop than we did and they seemed to hold the central ground as well.

Sheffield in the 70s was a hotbed for trouble at football. In 1973, United fans topped a football league of shame. The United hooligan element had seen 276 arrests, with Wednesday finishing third in the table with 258 arrests. So, over a season, the two clubs had seen arrests totalling 534. Sheffield was fast becoming the home of football-related violence. The year before the table was published, there was large-scale disorder at United’s games throughout the season. In April 1972, Newcastle’s visit to Bramall Lane led to 54 fans being arrested, the return game saw a further 83 locked up, then a month later another 30 arrests were made during the game with Manchester United which saw running battles on the Shoreham Kop as Manchester’s Red Army battled it out with the SRA. When Chelsea’s visit produced another 41 arrests, Sheffield United games had now become a policeman’s nightmare. The stark reality of it all was in just four United home games there had been a total of 192 arrests.

Over at Hillsborough, Manchester United’s visit in the same season produced 113 arrests, although, of that amount, over 30 were juveniles. What is interesting is that the numbers of police allocated to the games at this time were around 120, although by 1976 the number of police keeping order at football had doubled.

At the Sheffield derbies nowadays or a high-profile game, over 280 police are now on duty, when the violence is nowhere near as bad or as out of control as it used to be.

So, although Wednesday may have held sway in our city through this period, it was very much in evidence that United had a large hooligan element. One of United’s older lads takes up the story about those days and perhaps the SRA’s best effort against the stronger EBRA.

EGG DAY

One thing I learned very quickly was everyone’s hatred of Sheffield Wednesday. My school had been predominantly Blades and the few pigs caused little or no animosity between the two but the feeling on the Kop was different.

‘Fuckin’ Wednesday bastards’ could be heard as the old man in the white coat took the large tin numbers around to the alphabet scoreboard at the Lane and the score was in Wednesday’s favour.

‘I hate them blue and white cunts’ was also regularly voiced, and the more we heard the sayings and got more into the scene, the more we grew to hate them as well.

At the following game, which was at home to Notts Forest, a plan was literally hatched. Hats off to the bright spark that came up with the idea but word spread around the Kop like wild fire. That word being to take as many eggs as you could carry to the derby game at Hillsborough in a few weeks’ time; an invasion of their Kop was planned and a new song rang around the Kop:

‘Don’t forget your eggs

Don’t forget your eggs

Ee-hi-adio, don’t forget your eggs!’

Egg Day soon arrived, one Saturday in September 1966, four 15-year-old Dronfield lads sneaked into Hopkinsons small holdings egg coup, their mission ‘the great egg snatch’. Scores of chickens roamed freely around the sheds and outbuildings, laying eggs willy nilly in makeshift nests. After collecting a carrier bag full, they caught the bus to Sheffield to meet up with around 250 fellow Blades who were meeting in the Pond Street bus station at midday. I had been in town since 11am, armed with a carton of eggs, obtained by leaving a note out for my mother’s milkman. Many of the Blades arriving also carried boxes of eggs. We set off on the three-mile trek with our banners, flags and eggs, picking up small groups of lads on the way as we walked through town. There wasn’t a copper in sight. We showed off our eggs to each other like they were some kind of invention that no one had seen before. ‘Look at them fuckers for eggs then!’

Reaching the bottom of Penistone Road, about a dozen or so Pitsmoor lads carrying a large banner joined us. The odd egg was chucked at any passing Wednesdayite we saw. On reaching the ground at half past one, we queued outside the Penistone Road End, which was Wednesday’s East Bank Kop, and paid the one-shilling entrance fee. I emerged at the other side of the turnstiles to see a group of Blades telling the lads that the coppers were at the back of the open Kop, searching everyone for eggs. The word must have got out about the plan we had hatched. I hid my eggs in some bushes and walked past two coppers searching dozens of youths as they entered the Kop.

‘Got any eggs?’ the copper asked me, patting my bush jacket. A couple of cartons lay at his feet.

‘No,’ I answered.

‘Go on then, in you go.’

At least 10 lads had sneaked by as he did this. I waited a few minutes, walked back out and collected my eggs, then, when I passed the same copper again, said, ‘You’ve searched me once.’

The ground was all but deserted except for us; we stood at the back of the Kop directly behind the goal waiting for the pigs to arrive. The plan was, at ten to three, the shout would go up, ‘Sheff United – hallelujah!’ and we would release our eggs en masse at the Wednesday fans below us. By two o’clock, 50 or so Wednesday had gathered in front of us, which proved too tempting for some of the trigger-happy Blades and a few rounds of ammo were released into their ranks. By 2.30, the ground was filling up, more Wednesday, more Blades and more eggs entered the stadium. At ten to three, 40,000 fans were in the ground and as the mass of Blades began singing and swaying the cry went up: ‘Sheff United – hallelujah!’ It was a sight to behold, nowhere to run, nowhere to hide, it was ‘raining eggs, hallelujah’. A great roar greeted the teams as they took to the pitch. Wednesday banners had yellow slime running down them.

‘Scrambled eggs, scrambled eggs!’ we chanted at the egg-covered Owls. Our ammunition was now exhausted, so we turned to coins and other missiles, such as stones from the banking behind the Kop. One of the young Dronfield lads (who later went on to have a distinguished career in the police force) was removed and thrown out of the ground by his later-to-be colleagues. The game ended in a 2–2 draw but the Blades had scored what we all thought was a late winning goal, only for it to be disallowed for offside. We left the ground en masse at the end of the game and marched down Penistone Road towards town, chanting, ‘We were robbed,’ but still laughing at the few egg-stained Wednesday fans we saw.