Читать книгу Disco Demolition - Steve Dahl - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

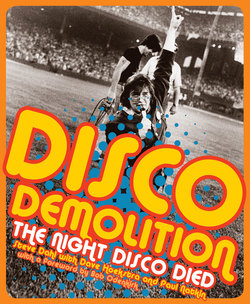

ОглавлениеPREFACE

DAVE HOEKSTRA

On July 12, 1979, the Chicago rock ‘n’ roll station WLUP-FM and the Chicago White Sox collaborated on a twi-night double-header originally called “Teen Night.”

After the events of the evening, it became known as “Disco Demolition.” Fans who brought a disco record to Comiskey Park would be admitted for ninety-eight cents (FM 97.9 was WLUP’s “The Loop” position on the dial) to see the Detroit Tigers play the White Sox.

In the center of the country, American music was at a crossroads.

And Comiskey Park was a rock ‘n’ roll Gettysburg. What followed was one of the greatest promotions in the history of Major League Baseball. The White Sox had been averaging about 20,000 fans a night in a grand old stadium that seated close to 50,000. Neither team was very sexy in the standings. The White Sox were 40-46, in fifth place in the American League’s Western Division. The Tigers were 41-44 in fifth place in the Eastern Division.

About 70,000 people showed up for the game.

Security quickly got out of hand as the audience discovered vinyl records made great Frisbees. Several players rightly remarked they were afraid of getting hurt by a Commodores single. After the White Sox lost the first game 4-1, the promotion took place in center field. WLUP morning personality General Steve Dahl and his sidekick Garry Meier led their Insane Coho Lips Army to center field to blow up a large box of disco records. They were assisted by WLUP’s provocative “Goddess of Fire” Lorelei Shark as General Dahl led the crowd in chants of “disco sucks!”

When the records blew up, the audience flooded the field. Fans tore out seats. Bonfires were lit with pocket lighters. Chicago police arrived at White Sox Park on horseback. The second game was canceled. Disco Demolition became the first and only event other than an act of God to cause the cancellation of a Major League Baseball game. (The Cleveland Indians’ “Ten Cent Beer Night” in June of 1974 also resulted in a riot; the game was forfeited in the ninth inning.)

White Sox president Bill Veeck was the king of baseball promotions. In 1976, the White Sox were ready to move to Seattle, until Veeck bought the team from John Allyn. One of Veeck’s promotions during his inaugural year was outfitting his players in clam diggers and hot pants. No trend was too small for Veeck. And in 1979, there was Disco Demolition. “I was amazed,” Veeck said afterwards. “We had anticipated 32,000 to 35,000. We had more security than we ever had before. But we had as many people in here as we ever had.” The security at Disco Demolition was as innocent as a Dan Fogelberg song compared to that of U.S. Cellular Field in the summer of 2015.

The passage of time has shed a different light on Disco Demolition; the events can be refitted to today’s values. Dahl told me, “Most of the people calling it racist and homophobic are younger and have come out of college predisposed to think that thanks to identity politics.”

The front page headline of the July 13, 1979 Chicago Tribune sports section read, “When fans wanted to rock, the baseball stopped,” and columnist David Israel wrote, “Ten years after Woodstock, there was Veeckstock . . . As far as riots go, this one was fairly lovely. I mean, it isn’t going to make anyone forget Grant Park or the Days of Rage. It was a lot of sliding into second base and ‘Look-at-me-Ma’ jumping around for the benefit of the television camera.” After all, the Sister Sledge disco tune “We Are Family,” co-written by Nile Rodgers, was one of the hits of the summer of 1979. (It even became the theme song for the Pittsburgh Pirates.)

On the flip side, in December 1979, rock critic Dave Marsh wrote of Disco Demolition in Rolling Stone, “White males eighteen to thirty-four are the most likely to see disco as the product of homosexuals, blacks, and Latins and therefore they’re the most likely to respond to appeals to wipe out such threats to their security.”

Veeck was a pioneer in the civil rights movement. He joined the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) not long after he purchased the Cleveland Indians in 1946. He hired African Americans to work in all parts of Cleveland Municipal Stadium, from beer vendors up through the front office. In 1947, he made Larry Doby the first African American baseball player in the American League, and in 1948, Veeck signed Negro League-legend Satchel Paige. New York’s New Amsterdam News called Veeck “The Abe Lincoln of Baseball.”

Disco Demolition was about class structure and music. At one time, disco was full of adventure and risk, like its offspring house music. Disco’s roots are full of integrity, ranging from the breathy raps of Isaac Hayes to the lean uptempo arrangements of Kenneth Gamble and Leon Huff. The 1974 Gamble-Huff MFSB instrumental “TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia)” is regarded as one of the primal disco hits. But by 1979, much of disco was defined by excess.

That summer, disco was dancing in an air of testosterone. John Wayne, America’s cowboy, died that June, and Ronald Reagan was in the bullpen for the 1980 election. Burt Reynolds had been named the best box office attraction in the country (1977 through 1981) in a poll of movie exhibitors.

During the summer of 1979, I was writing for a suburban Chicago newspaper while exploring the periphery of urban music. I loved the reggae-punk sound of The Clash and discovered the electric funkateer who called himself Prince. I was a huge Faces fan and was repulsed with the Rod Stewart hit “Do Ya’ Think I’m Sexy?”

That’s what led me to Disco Demolition.

I liked the Latin-tinged “disco” music of Tavares, the soul of the Ohio Players and the best orgasmic stuff from Donna Summer. But rock ‘n’ rollers crossing over into disco was wrong. Much later I would find out “Do Ya’ Think I’m Sexy” lifted the melody from the composition “Taj Mahal” by Brazilian artist Jorge Ben Jor. Jor filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Stewart and the case was settled amicably.

I love baseball more than Faces and the Stones, so it was easy to fork over ninety-eight cents on July 12, 1979, to catch the White Sox play a double-header with the Detroit Tigers. I liked Steve Dahl and Garry Meier. Their candor and real life approach is what made them appealing to an army of seekers and dissenters.

In 1979 I was living in an apartment a block east of Wrigley Field and dating a woman called Miller. She was from the far South Side neighborhood of Beverly and had eight sisters and one brother, a full starting line up of Sox fans. I was a Cubs fan. Miller and I took the El down from the North Side and got to the park early. I don’t recall seeing the thousands of people who later gathered on the outskirts of Old Comiskey Park. It was a hot, steamy night. We sat in the upper deck in right field. I behaved myself, likely because I didn’t drink Schlitz or Stroh’s, the Comiskey house beers.

The dimly lit upper cavern at Comiskey invited anarchy even on the quietest of nights. It was a good place to make out, guzzle from open bottles of Jack Daniel’s, and ignore the game. My father, who worked in the nearby Union Stockyards as a young man, took me to my first Major League Baseball game at Comiskey: White Sox-Yankees, 1965, with Mickey Mantle stumbling around on his last, weary legs.

The White Sox had a 40-46 record on July 12, 1979, and were not a very notable team. Disco Demolition may never have happened had the White Sox been compelling to watch.

Left fielder Ralph “Roadrunner” Garr had seen his best days with the Atlanta Braves and no longer deserved the nickname. Right fielder Claudell Washington became a punch line of a bad joke. (But he hit three home runs in a game on July 14, perhaps inspired by Disco Demolition). With such a blank canvas, WMAQ-AM radio announcers Harry Caray and former major leaguer Jimmy Piersall became the life of the party.

Owner Veeck would do anything to bring fans into the park to see his mundane cast of characters. Only a month before Disco Demolition, Veeck presented “Disco Night,” holding a dance contest before a game against the Seattle Mariners (according to a 1979 White Sox program I saved). June 23 was Lithuanian Day and August 20 was “Beer Case Stacking” Day. Veeck knew his South Side audience.

Former White Sox pitcher Ken Kravec said, “We had a good year in 1977, and Veeck was promoting. I was warming up in the bullpen when it was ‘Belly Dancer Night.’ There were thousands of belly dancers. They opened up the center field gates and here they come. As they come through the gate, some belly dancers go left and some go right. You had to track around the field. I’m warming up, no big deal. All of a sudden they walk between me and the catcher. I asked security, ‘Can you get them to walk over by the side so I can keep warming up?’ Something was happening almost every night.”

The White Sox lost the first game of the Disco Demolition double-header 4-1 on a nifty five-hitter from the Tigers’ Pat Underwood, a native of Kokomo (not the Beach Boys city) Indiana. Between games, Dahl entered the field on a Commando Jeep as the leader of the “Insane Coho Lips,” his anti-disco army, joined by Lorelei. Dahl wore military fatigues and a crooked helmet.

Dahl and Lorelei landed at second base and led the crowd in chants of “disco sucks!” There was a box of disco records on the outfield side of second base. Many fans took records to their seats. Then the records were blown up, and all hell broke loose.

About fifteen minutes before the second game was to begin, fans stormed the field. I didn’t throw my Rod Stewart record on the field; I had given it to the ticket taker. My clearest memory of that night is the cloud of smoke that hung over the field. “Beer and baseball go together; they have for years,” said the late Tigers manager Sparky Anderson. “But I think those kids were doing other things than [drinking] beer.”

Once the riot began, Miller and I departed immediately. There was no pushing or shoving to get out of “The Baseball Palace of the World.” Maybe most of the fans were on the field.

Thirty-nine fans were arrested on charges of disorderly conduct, but there were no reported injuries. At first, the second game was postponed, but American League President Lee MacPhail ordered a forfeit to the Tigers the following day. It would be the last forfeit in Major League Baseball until 1995, when Los Angeles Dodgers’ fans threw souvenir baseballs on the field, resulting in a forfeit to the St. Louis Cardinals. The announced attendance for the Disco Demolition game was 47,795 people. Bill Veeck guessed that between 50,000 and 55,000 people were in the ballpark. The capacity of Comiskey Park was 44,492. Chicago police were worried that crowds outside would also riot, but that never happened. Over time, Disco Demolition assumed the fable-like characteristics that are so common to baseball: 70,000 people were in the ballpark; 10,000 people were on the Dan Ryan Expressway in front of the ballpark. It was big, but not that big.

After the game, Sox pitcher Richard Wortham told reporters he was a fan of Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson, and then added, “This wouldn’t have happened if they had country and western night.”

Wortham’s teammate Thaddis Bosley, Jr. is one of the most thoughtful of the more than fifty people I interviewed for this book. Born in Southern California in 1956, his fourteen-year Major League Baseball career included stops with the Chicago Cubs (1983–86) and the White Sox (1978–80). After Bosley retired in 1990 he became a coach for the Oakland Athletics and hitting coach for the Texas Rangers. Bosley continues to pursue his first love of songwriting, releasing original songs in vintage soul and gospel genres. He writes poetry in his spare time.

Bosley split the 1979 season between the White Sox and their Class AAA affiliate in Iowa. He hit .312 in thirty-six games for the White Sox while battling injuries.

“I remember Disco Demolition, but truthfully I don’t remember if I was physically there,” he told me in September 2015 on a break from his job as executive director of athletics at Grace University, a private Christian school in Omaha, Nebraska. Such honesty is a good sign. Today, everyone says they were there. “Some of the guys told me how afraid they were,” he continued. “I specifically recall that during that time there was a tremendous transition of musicology. From an industry standpoint there seemed to be a push into disco music even though traditional rockers weren’t into that. The backdrop of the Comiskey event had some of those undertones. People said it was racially motivated. I don’t know if it was or not, but there certainly was a divide into what traditional rock should be versus disco.”

Bosley was traded from the California Angels to the White Sox in 1977. He played for the White Sox from 1978 until the spring of 1981 when he was traded to Milwaukee. In 1983, he was traded back to Chicago, this time to play for the Cubs.

“Chicago was a whole new dynamic for me,” Bosley said. “I had never experienced segregation like that. Chicago in the late seventies was very stressful for me. Then the whole Comiskey Park incident, you know how things implode? It seemed like things exploded in terms of what was really going on, not only in the cities but in the nation as a whole, as far as music was concerned.

“The thing that fascinated me the most about the event is that, boom, the next day disco died.”

Bosley got quiet as he collected his thoughts. “After that there was a shift. When I was traded to the Cubs I ended up buying a place in downtown Chicago and lived there for twenty-three years. That’s a reflection of how much the shift occurred. Harold Washington became mayor of the city (in 1983). A lot of good things birthed themselves out of that experience, out of that time.”