Читать книгу Fram - Steve Himmer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Back in their own office, back down the hall, the prognosticators set to the day’s agenda. Alexi proposed a lumberyard and sawmill and Oscar added a workers’ café. They agreed on a technical college founded on the south shore of Cornwallis Island only to discover the tractor and plow factory built there by Dimchas years earlier, so relocated the college to the north end.

At lunchtime Alexi stepped out, saying he needed to make a phone call—which required a trip upstairs to street level to have any chance at a signal—but Oscar ate a sandwich at his desk and kept working. Director Lenz’ announcement was enough disruption for one day to handle. When Alexi returned, Director Lenz buzzed the intercom and asked for him—and only him—to come to his office. Oscar had never been summoned alone to the director’s office and in all his years at BIP he’d never seen Slotkin called alone to the office, either. Alexi wasn’t gone long before he came whistling back to his desk and Oscar tried not to wonder what his new partner and Director Lenz might have talked about. Paperwork, probably. Tax forms.

He spent the afternoon filing building permits backdated a decade, creating receipts and invoices for the materials used in constructing the college, and entering that paperwork into the database that made it all real. Meanwhile, Alexi, with his knack for everyday appetites, compiled electronic records of ten years’ worth of paperwork related to groceries and other necessities of daily living a technical college might have: the pencils and notebooks, the toilet paper, the aspirin and condoms and antacid tablets to stock the campus infirmary. Between the two of them they created a whole institution that existed only on paper, or not even on paper but only in electronic records of paper that never existed. Oscar made the blueprints by copying some standard BIP templates for education (designs that had been adapted, slightly, for hospitals and prisons over the years) and once they were ready he logged them into the records of Northern Branch, the satellite office responsible for administering all Arctic construction. In theory, at least: Slotkin hadn’t known if Northern Branch really existed so neither did Oscar; it may have been another shell in the game of BIP records and perhaps there was even another office, some other department, responsible for inventing government offices when they were needed, a Bureau of Bureaucratic Prognostication. Whether Northern Branch was actually up there or not was irrelevant to Oscar’s work so he’d never worried about it and didn’t that day. Meanwhile, Alexi wrote rosters of past and present students, even those set to enroll for the fall term, and logged those records into the database, too.

The Cookies, those bitter losers, complained the BIP way was to rest on their laurels, to keep talking up the same old expeditions without taking fresh risks, not that they knew the half of how BIP actually worked. But BIP were government and the NGO Cookies assumed they had infinite funding, so they went on in their bulletins and listservs about the nobility of “real” exploration, of actual men going to actual places, always toward the goal of bumping off Peary as first to the Pole and restoring their own Frederick Cook to history’s good graces. They’d been at it for years, spreading rumors and sparking arguments the wider world knew next to nothing about, verbal skirmishes in Arctic enthusiasts’ magazine pages and later online, the occasional theft and counter-theft of some artifact or some piece of supposedly “last word” evidence, since April 1909 when the fight over who’d reached the Pole first flared up. It had been in the papers for a while, of course, big news in its day and scandal enough to destroy Cook’s career, yet by Oscar’s time no one knew but the descendent participants that the dispute simmered still and sometimes boiled over long after history had set it aside. They talked a good game among the musty oak panels and threadbare armchairs of their club downtown but the Cookies never went anywhere close to the Pole, no closer than BIP (which was, officially, in Peary’s camp, not that it mattered much day-to-day), because exploration costs money and the Arctic was a hard sell to those with deep pockets and purses, unlike in Peary’s day when business scions and industry’s leading lights had been eager to attach their names to each expedition.

Even space had become a hard sell though you’d never know it from NASA’s brave face, shameless as the men of BIP found it. Retroactive discovery and prognostication were more cost effective, exploring backward rather than forward by deciding what was already discovered then laying a paper trail to it. If the records say a campus was already constructed, that a sawmill or shipyard or even a beachfront resort with a volleyball court on frigid Ellesmere Island is there and already paid for, if the paperwork is all in place then it’s so. As far as anyone knows. And in a region where it’s unlikely anyone would venture to check, saying so had always been enough to ensure the next year’s budget.

That’s what Oscar and Alexi were told weekly by Director Lenz and no doubt it’s what he was told by whoever told him what to do. Maybe the Suit and the Stars.

After all, the argument had gone at the founding of BIP and each time Director Lenz refreshed his underlings’ motivation, who ever goes to the Arctic? Who but the great men who discovered great things and died out a long time ago? Those great men and now, for some reason, the two of them. Oscar and Alexi. They may not be great, and were often reminded by their director they weren’t, but think of the money they’d saved with their work. Think of the places they’d prevented the country from spending its taxes and resources and manpower to visit, by proving we’d already been there and so had no need to go back. Perhaps they’d even saved lives.

There were days Oscar’s discoveries felt so important, when he felt so successful, he wanted nothing more than to tell his wife what he’d done. He’d rush home picturing how proud she would be but it was an exercise in futility: he never told her and he never could because secrecy was rule one of BIP. Secrecy even from spouses. So instead he’d get home and when Julia asked, as she always did, how his day had been, he’d have nothing to tell her but, “Fine.” On regular days, days when he hadn’t done what felt like great things, he could make up a story about color coding or some especially challenging new filing system required by the Division of Aquatic Categories or whichever agency first came to mind. He could even conceal what he’d really done with a code of his own, telling his wife he had come up with a breakthrough alphanumerical system allowing twice as many files to occupy the same space when what he was actually talking about was discovering a lost colony on some Arctic spit.

But on the best of his days, days like the one when he discovered Symmes’ Hole, he had nothing to say; the gap between the truth and the best possible lie he might find to hide it was simply too great. So those days he most wanted to share with his wife were the days he could tell her the least and the days Oscar felt loneliest. He worried this would be one of those days, because how could he tell her he was off to the Arctic? What made up story about filing systems could communicate the wonder of that?

He and Julia would arrive home at the end of a day, ask each other how their day had been, and each of them would say, “Fine,” leaving nothing to talk about next. He’d even started to wonder if the work in a subdivision of Transportation Julia sometimes told him about—sharing funny moments from the Registry of Approved Tires and Treads—was in fact what she did all day or if she had an unmentionable job of her own, because hours at home with the familiar made strange by their silence were often as quiet as hours at BIP.

As quiet as he and Alexi were for a few hours that afternoon, each at his own terminal, but Oscar’s head whirled with possibilities about the expedition Director Lenz was sending them on as he waited for the appropriate obsolete building permit template to load on his screen. BIP’s computers were slow and the joke that went back further in that office than Oscar was that each time they asked a document to load or a query to run the bits or bytes or whatever they were had to mush all the way to the Arctic to pick up the file from Northern Branch, then mush all the way back. And there wasn’t much to do while they waited because those computers weren’t online, not really: BIP had its own intranet containing all its records and work, so Oscar could access what Alexi was doing and what Slotkin had left behind and even electronic versions of everything older, but he couldn’t check email or read websites or—worst of all—check the North Pole web cam for hours at a time. They were cut off with only each other to talk to, so at least they had that in common with the great men of the Arctic. They had their own jokes and their own secret stories, as Parry had his expedition’s newspaper, or they’d had those things until the past couple of weeks because Alexi wasn’t yet up on the lore of the office so there wasn’t much to talk about.

But when Oscar couldn’t keep it to himself any longer, and assuming his partner, too, had been wondering all afternoon, he asked Alexi, “What do you think we’re being sent for?”

“Sent where?” his partner replied, distracted by the list of names he was inventing for the technical college’s honor roll of three years back.

“To the Arctic! The job Director Lenz talked about. It was only this morning, Alexi.”

“Oh, right. That. I don’t know, maybe a convention or something? I kind of forgot. What do you think? What was it before?” The lightbulb above them swayed with sudden vigor and in the same seconds Oscar’s monitor flickered—the power cord socket was loose and had been for years, and it always suffered when he bumped or kicked the wrong spots in the frame of his desk—and in those two simultaneous wavering lights his eyes swam. He felt dizzy and not quite himself, more a sailor at sea; he felt a bit like Franklin adrift in the ice for those slightest of seconds, not to make too much of it, and gripped the arms of his chair with eyes closed until the waves passed and he sailed again into the calm harbor of BIP’s basement office, guided back by the gibberish morse code of Alexi tap-tapping his keys.

“There never was a before. BIP’s never sent anyone north as far as I know so I can’t begin to imagine,” he said. “The Arctic, though. We’re going to the actual Arctic. That’s what he was saying, right?”

“I hope they give us a decent dining allowance.”

Alexi’s obsession with food, his one track, digestive tract mind was almost charming to Oscar for the first couple of hours they worked together but soon it began to annoy him, and how could it not? But he was trying to get used to it, trying to accept it as the way of the world or at least the way of the work while he worked with Alexi, because they would likely be partners for years to come. That’s how things go, how they must go, when men work in the close quarters and isolation a region like the Arctic necessitates. But there had already been moments when Oscar wished his new partner had a little more to him than impulse and appetite, even if it was for the sake of competitions which, by his own account, Alexi was pretty good at.

He’d asked a week or so ago how Alexi came to join BIP but all the answer he got was, “Oh, you know, I’ve moved around,” and in government work that was a hint not to ask any more questions—either the story wasn’t interesting enough to dig for or was more interesting than the inquirer wanted to know.

“When do you think we’ll go?” Oscar asked. “Director Lenz said we’d receive more instructions.”

“Whenever we’re meant to, I guess.” Alexi had stopped naming students and was reading the entertainment section of a newspaper he’d brought from outside after lunch.

Despite himself, despite the protocols of government work and the honor of Arctic explorers, Oscar gave in and asked if Director Lenz had told Alexi anything in their second meeting.

His partner turned a page and said, “Hey, the new season of To The Moon! starts tonight.”

Oscar groaned. “I can’t stand that show. Who cares about space? Who’s impressed by all that? I mean, if the idiots who win that show can go up, how hard can it be? It’s not a dog team to the Pole.”

“Five o’clock,” said Alexi, already standing and in motion toward the door and the end of the day. “See you tomorrow.”

Oscar said goodnight and shut down his computer, then he cleaned up the papers spread on his desk and filed them in the right drawers, sighing at the left behind chaos of Alexi’s own desk. He checked that the drawers were all locked, his own and Alexi’s, in case someone came wandering in; Oscar assumed and had for years that somebody ran through the office at night with a vacuum because the carpet had maintained a consistent level of dingy without giving over to filthy for as long as he’d worked in that basement. He checked the drawers in the archival cabinets where neither he nor Alexi ever had cause to roam, nor had Slotkin in the course of most weeks and months. Once, though, a few years earlier, Oscar had consulted that cabinet and its crisp, yellowed pages for details on brick manufacturing trends from Bylot Island—he needed to explain why the region’s largest brickworks had relocated to North Cornwallis—and in the course of that journey into BIP’s material past had discovered something surprising. In a fat, brown folder of pages, maps and records and lists and diagrams, he found a full accounting of the Jeannette, of her ill-fated voyage in search of Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld and his own vanished ship Vega. The details of the voyage didn’t surprise him; like any Polar enthusiast he was long familiar with DeLong’s abandonment of Jeannette near Wrangel Island after she froze into the pack ice. He knew how her crew had been scattered, wandering over the ice, but also how they had first tried to drift, to let themselves be stuck fast and slide toward the Pole on slow currents, only to have their ship sink and leave them stranded.

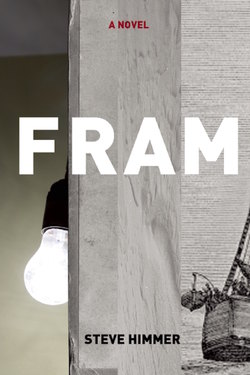

He knew because it was the unexpected drifting of DeLong and Jeannette that gave Nansen his vision, to build a ship intended to freeze and to drift, a ship meant not to fight for its own motion or set its own course but to equip its captain and crew for a long, patient wait. The kind of deep patience the Inuit call quinuituq, another word Oscar tried to work into conversation whenever he could. And for Nansen it had worked out so much better; rather than lose his ship he brought Fram safely to port with such stories to tell about months doing nothing in ways that meant everything.

He knew because Fram and her patient journey, her passive quest, was Oscar’s own favorite of all the Polar excursions. He admired Peary and Franklin and all the others, of course; he admired his American forebears with the pride of any government worker of any grade, but Nansen was the explorer who meant the most to him, the one whose words echoed loudest in Oscar’s mind from all his re-readings of Farthest North.

But that wasn’t the point of what he’d found in the filing cabinet, in that old folder full of old pages left behind by Wend, according to the handwriting inside. What he’d discovered was an account of the Jeannette, yes, but not quite the way things had happened: Wend had rewritten the voyage and the aftermath of its loss to the ice. He’d created records to show all the crew had come home, those who drowned in a launch and those who wandered to their death on the Siberian tundra alongside DeLong. Wend had filed tax returns and love letters written after the fact, he’d made accounting claims and real estate deeds and applications for library cards, as if none of those men had been lost on the ice. As if they’d all come back for long lives. Wend had filed obituaries for each of them, deaths by cancer and car crash and fire, but not one of them frozen up north.

Oscar had never mentioned those files to Slotkin or to Director Lenz or to anyone else. Certainly not to Alexi. He’d checked the database, though, to be sure Wend hadn’t put all his rewritten sailors in there; old paper in the back of a drawer was one thing but in the database, in electronic form with the long reach of wires, someone might notice and who knew where suspicion might fall. But sometimes, like that afternoon while locking up for himself and Alexi, he checked to make sure the folder was still where it belonged, whether it really belonged there or not.

Finally, using an old handkerchief kept for the purpose and left behind by a predecessor of his predecessor, so long ago the handkerchief itself sometimes came into productivity lectures as an inspiration in its own right—the subservient ego, the selfless sidekick and all of that; the bulb’s Matthew Henson, perhaps—he reached up to straighten the lightbulb left swaying by his partner’s departure before leaving the office himself, though he wondered, as always, if it would start swaying again when he’d gone. Would the residual heat left behind be enough to keep that faithful underground sun in motion?

Oscar climbed the dark stairwell from BIP’s basement into the lobby of an unremarkable building housing government departments unknown to all but the interchangeable bureaucrats working in them, and in which he’d spent all of his working life beginning with an internship during college. Weights and Measures upstairs, BIP in the basement, the Division of Agricultural Categories on the third floor, and some others he didn’t know because in all those years Oscar had never once taken time to read the whole orientation board in the lobby. He was content to keep his knowledge of the building and its occupants on a small scale. To stick to what he already knew.

If the basement of BIP was stuck in a bygone era of quasi-Soviet green and gray with all its whites yellowed, then the building’s lobby above was capitalism’s future as seen by the past: glass cubes, soaring ceilings sliced by odd architectural angles so whispers bounced until they were shouts, and steel tube furniture with plush pleather square cushions that squeaked and exhaled when you sat. But no one was sitting when Oscar emerged from the basement and no one was standing still, either. Every body in that bureaucratic cathedral was in motion from the elevators and stairwells en route to the exits: brown suits, blue suits, jacketless shirts and black skirts, all flowing together toward the revolving glass doors and bright street outside.

Cell signals and wifi couldn’t penetrate the fire doors and blast ceilings down to BIP’s basement, but once in the lobby Oscar pulled out his phone and went online to check the North Pole cam as he always did. The ice was calm, with only a slight wind across it stirring clouds of snow every so often, and as he watched he relaxed, his fingers at ease against the grained texture of his phone’s case; he’d seen cases of actual wood and had nearly bought one, but the plastic wood seemed more practical, more durable, yet more palatable—closer to the compasses and map cases of real wood the great men relied on—than the dull, gleaming alloy of the naked object itself. A lens flare in the far off northern sky trailed purple and orange orbs like a comet and pockmarks like footprints led away from the camera toward the haze of horizon. They weren’t actual footprints, just cracks and holes piled with snow and slightly lower than the ice sheet around them; they appeared often within view of the cam and Oscar knew why, but they still suggested footprints as if he’d just missed someone up at the lens before he logged on. He liked to imagine he had. He liked to imagine his own checking in had almost coincided with the arrival of some expedition though he would have known if a real expedition to the Pole was underway—it would have made the blogs, or shown up in the automated news searches that emailed him whenever the Arctic was mentioned.

Still looking down at the screen of his phone, Oscar merged with the building’s bureaucratic foot traffic and was ejected into the glare of Washington, DC’s lingering Indian summer and the heat hit him hard. The ice sheet went spotty, awash with dark stars for a few seconds as he stood blinking on the sidewalk, surrounded by his fellow government workers all blinking, too, many of them looking at their own phones—perhaps at the Pole cam, who knows, but more likely squinting at email or text messages or traffic reports; they all worked upstairs where cell signals reached and wifi worked so they weren’t catching up on a whole day’s passage as Oscar was. They weren’t taking their first look at the ice sheet in hours.

A text message popped up on his screen, from Julia hours before, telling him she’d be late after work, don’t wait up, some of her friends from a karate class she’d been taking were going out. It happened more and more often, whether karate class or late meetings or last-minute trips, and Oscar suspected he and his wife had more conversations by voicemail and text than in person. He’d begun to keep track one month but after a couple days’ record keeping the data were already sufficiently dispiriting to make him stop.

Oscar liked texts and voicemail. He liked the way he could come out of work, step into a signal, and they’d all come at once. Like it had been for Peary and Nansen and all the others, sailing into port after months or years in the ice, or running into a whaling ship carrying letters, and catching up on what had happened elsewhere only after the pressure of the moment had passed. A welcome soaking after a drought, all those letters and all that lost time at once, though the possibilities for failure were deepened: to be the crewman with no letters waiting, the days Oscar emerged but no messages pinged on his phone.

Beads of sweat ran from under his hair down his forehead and into his eyes, and he wiped them away with a sleeve without taking his gaze off his handful of cold northern desert. He held the phone at arm’s length and almost horizontal to lessen the glare as the shadow of a bus stopping in front of him fell upon both his eyes and the screen. The ice gleamed white as the marble of the city around him, the monuments, the columns, the glare of the Capitol dome, and each car window and side mirror flared silver as it grabbed every available particle of light from the air and condensed them, concentrated, into a thousand small suns that made walking down the street a minefield for the eyes. Everyone spilling out of those buildings, himself included, did their best to avoid any reflections and every few seconds a glistening government employee walked behind the extended screen of Oscar’s phone, picking at his or her sticky clothes or wiping sweat from a face, partly hidden behind the snowfield as they passed, a partially disembodied explorer passing across the top of the world and it jolted his eye when they didn’t appear at the Pole.

A souvenir vendor stood by his overloaded shopping cart hawking inflatable Washington monuments and cheap sunglasses and T-shirts bearing logos for the CIA and FBI and NASA and, in a stack that had either started out smaller or sold very well, for the IRS, too. Often, daily even, Oscar forgot there was so much light in the world while working in BIP’s basement under that singular bulb. It was easier in winter, when the Pole cam on his phone was dark after work and all day, when the sun had already set over Washington by the time he emerged for his commute home. But regardless of season, regardless of light, it was disorienting no matter how often he did it—and he’d done it for years—to pop out of the past back into the present at the end of a day, from a department where nothing changed and time passed backward and in the abstract, always alterable after the fact, into a present where the past existed only as a sales pitch for the future.

Eyes adjusted, he walked toward the Metro in the same direction as everyone else save the few who hailed taxis and the fewer still headed for private cars in parking lots and the odd duck from Agricultural Categories who day after day hauled his bike up and down the stairs to his office rather than lock it to the bike rack outside like all the other cyclists who worked in the building. Oscar held his phone close at an angle that let him keep one eye on the street, watchful for curbs and crosswalks and fellow commuters, while the other could watch the ice sheet for action, until he descended into the station.

His shot sliced only an inch or two wide of its mark, close enough to kill the creature regardless, in time. But off by enough to keep the caribou bleeding for hours which he couldn’t stomach. So when it staggered away the hunter crossed the distance between their two bodies and pushed into the brush on its trail, following breadcrumbs of blood. He hadn’t come north to leave things undone.

He heard stunned legs stumbling, an off-kilter body not heeding commands, bumping trunks and tripping over itself. Despite injury and blood loss and no doubt confusion the caribou managed to stay ahead, to always be on the far side of a gully when the hunter arrived or up the first leg of a switchback with him at its foot.

The day dragged on like that but he followed. Each extra meter or mile made him feel worse for the creature, let him borrow more of its pain, and the notion he was preventing its suffering by driving it on a long chase became more absurd the longer it went. But this was his mess, his mistake, and he would make things as right as he could.

He was thirsty but didn’t drink because the caribou hadn’t stopped to drink either.

He was hungry but the trail mix and pemmican remained in his pack.

He walked while the creature kept walking.

And there it was, close enough to take a new shot—not a retake, never those, but a chance to finish what had taken too long and what, had he known, he would not have begun.

The caribou wobbled below him on a scree slope then buckled onto front knees; the side facing the man was matted and running with blood. Its tongue draped low from far back in the mouth and the auburn chest heaved as the hunter took the clean shot he should have taken before.

It was done.

He slid sideways through the loose stones, stopping himself beside the carcass, then looked back up the slope wondering how he would haul that still-warm weight to the trail. He took hold of one foreleg and one hind, dug in his heels, and tried to work his way up by pushing with one foot at a time, alternating as if pumping some awkward machine, but the animal had hardly shifted before the hunter was spent.

He drank, taking water slowly to ward off the cramps and the dehydration headache he knew he deserved for dragging this out.

He tried again to haul the caribou up with no greater success. Now his arms were bloody, his boots and pants, too, and the animal’s thick, sticky fluid had soaked through his socks and run into his boots and oozed now each time he put weight on his feet.

One final attempt, pushing with both heels at once plus the boost of a keening yell that bounced back at him off the opposite slope. The weight of the animal dislodged all at once but instead of climbing toward him it slipped, freed from whatever had held it fast on the scree, and it pulled the hunter down with it; he let go just in time, barely keeping his own bloody body from following the other, the body he’d killed, off the edge of a cliff and onto the rocks far below.

The falling corpse carried with it the waste of a life, the waste of a day, weeks of meat lost for the hunter, his family, his village. He would return from his hunt empty-handed and his wife would tell him it was okay, they had enough in the larder to last, but the fan of wrinkles at the edge of each eye where for so long she’d squinted against harsh northern glares would tighten as it always did when she worried but wouldn’t say so.

This place. All its promise. Too much to leave now they’d come close to achieving what they came north to do, so close to cutting their ties to the world and untangling themselves from its net, but still. If there was something, just something, this place would give up to them more easily… if they found some resource they could sell back to the world, minerals or diamonds or gold, uranium or oil or even a way to send south the steam from the ground that powered their few contrapted machines, he wondered if the villagers would be willing to do it despite their ideals and the pronouncements they’d made upon packing up and heading north.

It was fortunate, in its way, that their excursions all over these mountains had given them nothing but berries and meat. Nothing to tempt them back into the web of the world. The decision was always already made for them.

The hunter leaned his head to his knees, cursed, and sat until his breath returned. Then he crawled up the slope, regained the trail, and walked back in the direction he’d come from toward where the mountains gave way to the coast and to home.

But it wasn’t a waste for everyone, that falling corpse. When caribou struck ground at the base of the cliff organs ruptured, bones cracked, and flesh tore. Before the thunderous waves of its impact reached the far point of their rippling across yellowed grass, flies lit on the syrupy blood of the wounds the hunter had provided them with and among the dark runnels congealed in the animal’s fur after walking so long with its heart pumping hard.

Those flies were already laying their eggs in rich layers of fat and of flesh before the body had cooled. Microbes descended out of the air and rose from the soil to penetrate every delectable niche. Foxes crept closer; a bear raised its nose into the wind with a snort and a sniff and shifted course toward the corpse; mosquitoes as large in actual fact as their southern cousins only sound in a dark, quiet room drew blood from the carcass and its four-legged diners alike.

How long would it be until every scrap of that carcass was broken down and devoured, and how long after that before every vestigial scrap of its generous energy had been exhausted in smaller bodies then in concentric tiers of even more bodies that fed second-proboscis through those? Generations of bacterium and black fly would rise and fall on that caribou’s haunches and a civilization of maggots and worms would reach the proportions of legend, an empire of gristle and blood in those vast dormant lungs, persisting through skirmish and snap-freeze and epidemics of food poisoning, perhaps someday half-remembered in wonder as another species might speak of Atlantis.

Elsewhere icebergs were crumbling. Elsewhere all signs were the Arctic was dying but here in the bloat and decay of a corpse there was life after death as millions of miniature stories were written in blood, an overflowing database of past, present, and future on the broken bones of a man’s failure.