Читать книгу Under the Dark Sky - Steven G. Smith - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

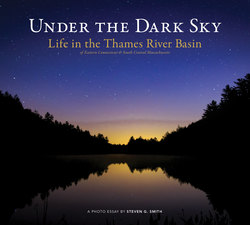

ОглавлениеForeword

Look closely at a map of eastern Connecticut; brooks, streams, rivers, everywhere. Drive the roads; small farms, small towns, small cities. Adjoining them are public and private forests spread over tens of thousands of acres. In the fields, and even in the woods, are centuries old stone walls, relics from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when all of eastern Connecticut was patchworked farmland. Along many of the waterways are old textile mills, some empty and windowless, some morphing handsomely into twenty-first century usefulness as condos, restaurants and shops. Along the coastline, or near it, are colleges, gambling casinos and heavy industry.

This is the Thames River watershed, a fluvial web of waterways from which the aesthetic and cultural soul of modern-day eastern Connecticut evolved.

Steven G. Smith, associate professor of visual journalism at the University of Connecticut in Storrs—the university itself is an enormous presence in the valley—has masterfully captured the essence of the Thames watershed in the pages that follow. The rivers, the forests, most of all the people, are here, the overall effect of his images providing a real sense of life in the region.

“In many ways, Eastern Connecticut is still the state at its truest; a place where the character, culture and natural beauty of this state remains largely untransformed by proximity to New York and Boston,” says Walter W. Woodward, associate professor of history at the University of Connecticut, the designated state historian, and a resident of the Thames River valley himself.

In Connecticut: A Guide to its Roads, Lore and People, a 1938 book produced by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Depression-era Works Progress Administration, eastern Connecticut is described as mostly rural, with a long, rich history. It was, for example, along a trail that passed through northeastern Connecticut—which became known as the Connecticut Path—that the state’s first European settlers arrived in the early seventeenth century. It was on the many streams of the Thames watershed that the Industrial Revolution flourished in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

“Streams are pure, swift, and boisterous,” the Writers’ Project authors wrote. Crossroads hamlets “cling to the edge of scattered farmlands.” More than 75 years later, nearly the same can be said. Wild, native brook trout, extirpated from much of the Northeast, still flourish in many of the brooks and streams in the northern reaches of this watershed. Hamlets like Phoenixville still exist.

Some of the wildest country in Connecticut is in the northeast, near the borders with Massachusetts and Rhode Island, where the landscape is dominated by large blocks of forest. Airline pilots flying the eastern seaboard at night know the area as the dark corner, a distinct expanse of black in the otherwise well-lit Washington to Boston corridor.

Perhaps the Thames River watershed can best be understood compared to a letter Y, the left fork being the Shetucket River and its tributaries, the right fork the Quinebaug River and its tributaries. Where they meet, at Norwich, they become the Thames, which flows to the sea.

Much of eastern Connecticut, however changing, however modern, is at the same time a window into the past, perhaps the last remaining expression of colonial Connecticut culture, Yankee culture, as it evolved over the centuries. “It’s where Connecticut’s revolutionary spirit first came to life and where the New Light of the Great Awakening shined brightest,” Woodward says. “Drive through its hills and valleys, paddle its rivers, or walk its trails—most of all, talk to the people of eastern Connecticut and you’ll understand what’s Connecticut about the Connecticut Yankee.” In places like Woodstock, change comes slowly, and the colonial and agrarian past is respected. Woodstock consists of nicely kept old homes and a town green, and produces a country feel, with woods never far away.

Eastern Connecticut might even qualify as a microcosm of New England history, shaped by the enormously powerful influences of early Puritan life, the American Revolution, waves of immigration, and world wars.

Today it is shaped by twenty-first century trends. Small farms, which declined precipitously in the nineteenth century, pop up again as people in recent years increasingly value local produce. Forests, which were cleared for farming in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, have rebounded so nicely since 1850 that in places they suggest the old growth forests that the first settlers encountered.

In the same watershed as Woodstock reside small towns like Griswold and Bozrah, far less affluent, but the kind of towns where a family tends a vegetable garden, where a pickup truck is often the vehicle of choice. Old mill towns, like Danielson, Willimantic and Putnam, are in some ways still struggling with the loss of the textile industry, yet virtually all of them are reinventing themselves after years of decay. In the Taftville section of Norwich, on the banks of the Shetucket, the nineteenth-century Ponemah Mills complex, for example, once the world’s second largest textile mill, is now a massive housing complex.

In the lower reaches of the watershed, from Norwich south, population density is higher, the roads are busier, and the Thames is now a tidal presence so vast it carries submarine traffic. Here, the watershed that begins in woods, part of it just above the Connecticut border in Massachusetts, blends into the eastern megalopolis.

Native people of this region have survived through centuries of colonization. Their ancestors were here in the Thames valley when the first European settlers arrived in the seventeenth century. Today, the Mashantucket Pequots operate the Foxwoods Resort Casino on their land in Mashantucket. The Mohegan Tribe, which has its reservation on the Thames in Uncasville, operates the Mohegan Sun casino on its land. The casinos are a significant economic driver in the state, and also support a world-class museum and education center for the study of Native history and culture.

Important state and national institutions are based near the Thames. The U.S. Coast Guard Academy and Connecticut College are highly regarded educational institutions near the mouth of the river. Pfizer, a global pharmaceutical company, has its research labs in Groton, where the Thames meets the sea. The General Dynamics Electric Boat Division, also in Groton, builds nuclear submarines for the U. S. Navy.

Smith spent three years traveling the watershed, photographing forests, streams, farms, homes, cultural events, and commercial and industrial institutions. Enjoy the photos on the following pages, for they amount to a distillation of the landscape and culture of a region that may well be the last remaining expression of an idyllic nineteenth century Connecticut.

— Steve Grant, 2017